Universiv Microtlms International 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

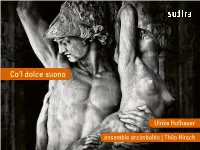

Digibooklet Co'l Dolche Suono

Co‘l dolce suono Ulrike Hofbauer ensemble arcimboldo | Thilo Hirsch JACQUES ARCADELT (~1507-1568) | ANTON FRANCESCO DONI (1513-1574) Il bianco e dolce cigno 2:35 Anton Francesco Doni, Dialogo della musica, Venedig 1544 Text: Cavalier Cassola, Diminutionen*: T. Hirsch FRANCESCO DE LAYOLLE (1492-~1540) Lasciar’ il velo 3:04 Giovanni Camillo Maffei, Delle lettere, [...], Neapel 1562 Text: Francesco Petrarca, Diminutionen: G. C. Maffei 1562 ADRIANO WILLAERT (~1490-1562) Amor mi fa morire 3:06 Il secondo Libro de Madrigali di Verdelotto, Venedig 1537 Text: Bonifacio Dragonetti, Diminutionen*: A. Böhlen SILVESTRO GANASSI (1492-~1565) Recercar Primo 0:52 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda pur della Prattica di Sonare il Violone d’Arco da Tasti, Venedig 1543 Recerchar quarto 1:15 Silvestro Ganassi, Regola Rubertina, Regola che insegna sonar de viola d’archo tastada de Silvestro Ganassi dal fontego, Venedig 1542 GIULIO SEGNI (1498-1561) Ricercare XV 5:58 Musica nova accomodata per cantar et sonar sopra organi; et altri strumenti, Venedig 1540, Diminutionen*: A. Böhlen SILVESTRO GANASSI Madrigal 2:29 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543 GIACOMO FOGLIANO (1468-1548) Io vorrei Dio d’amore 2:09 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543, Diminutionen*: T. Hirsch GIACOMO FOGLIANO Recercada 1:30 Intavolature manuscritte per organo, Archivio della parrochia di Castell’Arquato ADRIANO WILLAERT Ricercar X 5:09 Musica nova [...], Venedig 1540 Diminutionen*: Félix Verry SILVESTRO GANASSI Recercar Secondo 0:47 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543 SILVESTRO GANASSI Recerchar primo 0:47 Silvestro Ganassi, Regola Rubertina, Venedig 1542 JACQUES ARCADELT Quando co’l dolce suono 2:42 Il primo libro di Madrigali d’Arcadelt [...], Venedig 1539 Diminutionen*: T. -

The Motets of Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli in the Rokycany Music Collection

Musica Iagellonica 2017 ISSN 1233–9679 Kateřina Maýrová (Czech Museum of Music, Prague) The motets of Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli in the Rokycany Music Collection This work provides a global survey on the Italian music repertoire contained in the music collection that is preserved in the Roman-Catholic parish of Roky- cany, a town located near Pilsen in West-Bohemia, with a special regard to the polychoral repertoire of the composers Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli and their influence on Bohemian cori-spezzati compositions. The mutual comparison of the Italian and Bohemian polychoral repertoire comprises also a basic compara- tion with the most important music collections preserved in the area of the so- called historical Hungarian Lands (today’s Slovakia), e.g. the Bardejov [Bart- feld / Bártfa] (BMC) and the Levoča [Leutschau / Löcse] Music Collections. From a music-historical point of view, the Rokycany Music Collection (RMC) of musical prints and manuscripts stemming from the second half of the 16th to the first third of the 17th centuries represents a very interesting complex of music sources. They were originally the property of the Rokycany litterati brotherhood. The history of the origin and activities of the Rokycany litterati brother- hood can be followed only in a very fragmentary way. 1 1 Cf. Jiří Sehnal, “Cantionál. 1. The Czech kancionál”, in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie, 29 vols. (London–New York: Macmillan, 20012), vol. 5: 59–62. To the problems of the litterati brotherhoods was devoted the conference, held in 2004 65 Kateřina Maýrová The devastation of many historical sites during the Thirty Years War, fol- lowed by fires in 1728 and 1784 that destroyed much of Rokycany and the church, resulted in the loss of a significant part of the archives. -

Early Fifteenth Century

CONTENTS CHAPTER I ORIENTAL AND GREEK MUSIC Section Item Number Page Number ORIENTAL MUSIC Ι-6 ... 3 Chinese; Japanese; Siamese; Hindu; Arabian; Jewish GREEK MUSIC 7-8 .... 9 Greek; Byzantine CHAPTER II EARLY MEDIEVAL MUSIC (400-1300) LITURGICAL MONOPHONY 9-16 .... 10 Ambrosian Hymns; Ambrosian Chant; Gregorian Chant; Sequences RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR MONOPHONY 17-24 .... 14 Latin Lyrics; Troubadours; Trouvères; Minnesingers; Laude; Can- tigas; English Songs; Mastersingers EARLY POLYPHONY 25-29 .... 21 Parallel Organum; Free Organum; Melismatic Organum; Benedica- mus Domino: Plainsong, Organa, Clausulae, Motets; Organum THIRTEENTH-CENTURY POLYPHONY . 30-39 .... 30 Clausulae; Organum; Motets; Petrus de Cruce; Adam de la Halle; Trope; Conductus THIRTEENTH-CENTURY DANCES 40-41 .... 42 CHAPTER III LATE MEDIEVAL MUSIC (1300-1400) ENGLISH 42 .... 44 Sumer Is Icumen In FRENCH 43-48,56 . 45,60 Roman de Fauvel; Guillaume de Machaut; Jacopin Selesses; Baude Cordier; Guillaume Legrant ITALIAN 49-55,59 · • · 52.63 Jacopo da Bologna; Giovanni da Florentia; Ghirardello da Firenze; Francesco Landini; Johannes Ciconia; Dances χ Section Item Number Page Number ENGLISH 57-58 .... 61 School o£ Worcester; Organ Estampie GERMAN 60 .... 64 Oswald von Wolkenstein CHAPTER IV EARLY FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH 61-64 .... 65 John Dunstable; Lionel Power; Damett FRENCH 65-72 .... 70 Guillaume Dufay; Gilles Binchois; Arnold de Lantins; Hugo de Lantins CHAPTER V LATE FIFTEENTH CENTURY FLEMISH 73-78 .... 76 Johannes Ockeghem; Jacob Obrecht FRENCH 79 .... 83 Loyset Compère GERMAN 80-84 . ... 84 Heinrich Finck; Conrad Paumann; Glogauer Liederbuch; Adam Ile- borgh; Buxheim Organ Book; Leonhard Kleber; Hans Kotter ENGLISH 85-86 .... 89 Song; Robert Cornysh; Cooper CHAPTER VI EARLY SIXTEENTH CENTURY VOCAL COMPOSITIONS 87,89-98 ... -

The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I

The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I Edited by Theodore Hoelty-Nickel Valparaiso, Indiana The greatest contribution of the Lutheran Church to the culture of Western civilization lies in the field of music. Our Lutheran University is therefore particularly happy over the fact that, under the guidance of Professor Theodore Hoelty-Nickel, head of its Department of Music, it has been able to make a definite contribution to the advancement of musical taste in the Lutheran Church of America. The essays of this volume, originally presented at the Seminar in Church Music during the summer of 1944, are an encouraging evidence of the growing appreciation of our unique musical heritage. O. P. Kretzmann The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I Table of Contents Foreword Opening Address -Prof. Theo. Hoelty-Nickel, Valparaiso, Ind. Benefits Derived from a More Scholarly Approach to the Rich Musical and Liturgical Heritage of the Lutheran Church -Prof. Walter E. Buszin, Concordia College, Fort Wayne, Ind. The Chorale—Artistic Weapon of the Lutheran Church -Dr. Hans Rosenwald, Chicago, Ill. Problems Connected with Editing Lutheran Church Music -Prof. Walter E. Buszin The Radio and Our Musical Heritage -Mr. Gerhard Schroth, University of Chicago, Chicago, Ill. Is the Musical Training at Our Synodical Institutions Adequate for the Preserving of Our Musical Heritage? -Dr. Theo. G. Stelzer, Concordia Teachers College, Seward, Nebr. Problems of the Church Organist -Mr. Herbert D. Bruening, St. Luke’s Lutheran Church, Chicago, Ill. Members of the Seminar, 1944 From The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church, Volume I (Valparaiso, Ind.: Valparaiso University, 1945). -

High School Madrigals May 13, 2020

Concert Choir Virtual Learning High School Madrigals May 13, 2020 High School Concert Choir Lesson: May 13, 2020 Objective/Learning Target: students will learn about the history of the madrigal and listen to examples Bell Work ● Complete this google form. A Brief History of Madrigals ● 1501- music could be printed ○ This changed the game! ○ Reading music became expected ● The word “Madrigal” was first used in 1530 and was for musical settings of Italian poetry ● The Italian Madrigal became popular because the emphasis was on the meaning of the text through the music ○ It paved the way to opera and staged musical productions A Brief History of Madrigals ● Composers used text from popular poets at the time ● 1520-1540 Madrigals were written for SATB ○ At the time: ■ Cantus ■ Altus ■ Tenor ■ Bassus ○ More voices were added ■ Labeled by their Latin number ● Quintus (fifth voice) ● Sextus (sixth voice) ○ Originally written for 1 voice on a part A Brief History of Madrigals Homophony ● In the sixteenth century, instruments began doubling the voices in madrigals ● Madrigals began appearing in plays and theatre productions ● Terms to know: ○ Homophony: voices moving together with the same Polyphony rhythm ○ Polyphony: voices moving with independent rhythms ● Early madrigals were mostly homophonic and then polyphony became popular with madrigals A Brief History of Madrigals ● Jacques Arcadelt (1507-1568)was an Italian composer who used both homophony and polyphony in his madrigals ○ Il bianco e dolce cigno is a great example ● Cipriano de Rore -

Heinrich Isaac's

'i~;,~\,;:( ::' Heinrich Isaac's, :,t:1:450-1517) Choralis Constantinus::! C¢q is an anthology of 372; polyphonic Neglected Treasure - motets, setting the textsolthe Prop er of the Mass, accompanied by five Heinrich Isaac's polyphonic settings dflheOrdinary. A larger and more complete suc Choralis Constantinus cessor to the Magnus,iij:Jer organi of Leonin, the CC was fir~t 'pulJlished in three separate volum~s)' by the Nuremberg publisher j'lieronymous by James D. Feiszli Formschneider, beginning in 1550 and finishing in 1555'>:B.egarded by musicologists as a : ,',fsumma of Isaac's reputation prior to his move to assist him in finishing some in Netherlandish polyphony about to Florence.3 complete work. Isaac was back in 1500, a comprehepsive com In Florence, Isaac was listed on Florence by 1515 and remained the rosters of a number of musical there until his death in 1517. pendium of virtually :fi:llli devices, manners, and styles prevalent at the organizations supported by the Isaac was a prolific and versatile time"! the CC today'i~,v:irtually ig Medici, in addition to serving as composer. He wrote compositions in nored by publishers:'Cing, hence, household tutor to the Medici fami all emerging national styles, produc choral ensembles. Few!or.:the com ly. He evidently soon felt comfort ing French chansons, Italian frottoie, positions from this i,'cblI'ection of able enough in Italy to establish a and German Lieder. That he, a Renaissance polyphonyiihave ever permanent residence in Florence secular musician who held no been published in chqrat!octavo for and marry a native Florentine. -

I T a L Y!!! for Centuries All the Greatest Musicians Throughout Europe (From Josquin Des Prez, Adrian Willaert, Orlando Di Lasso to Wolfgang A

Richie and Elaine Henzler of COURTLY MUSIC UNLIMITED Lead you on a musical journey through I T A L Y!!! For centuries all the greatest musicians throughout Europe (from Josquin des Prez, Adrian Willaert, Orlando di Lasso to Wolfgang A. Mozart and so many others) would make a pilgrimage to Italy to hear and learn its beautiful music. The focus of the day will be music of the Italian Renaissance and its glorious repertoire of Instrumental and Vocal Music. Adrian Willaert, although from the Netherlands, was the founder of the Venetian School and teacher of Lasso, and both Gabrielis. The great Orlando di Lasso (from Flanders) spent 10 years in Italy working in Ferrara, Mantua, Milan, Naples and Rome where he worked for Cosimo I di Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. We’ll also play works by Andrea Gabrieli (uncle of Giovanni). In 1562 Andrea went to Munich to study with Orlando di Lasso who had moved there earlier. Andrea became head of music at St Marks Cathedral in Venice. Giovanni Gabrieli studied at St. Marks with his uncle and in 1562 also went to Munich to study under Lasso. Giovanni’s music became the culmination of the Venetian musical style. Lasso returned to Italy in 1580 to visit Italy and encounter the most modern styles and trends in music. Also featured will be Lodovico Viadana who composed a series of Sinfonias with titles of various Italian cities such as Bologna, Ferrara, Florence, Rome, Padua, Parma, Mantua, Venice and more. These city states are also associated with the delicious food of Italy, some of which we’ll incorporate into the lunch offering. -

A Second Miracle at Cana: Recent Musical Discoveries in Veronese's Wedding Feast

BASSANO 11 A SECOND MIRACLE AT CANA: RECENT MUSICAL DISCOVERIES IN VERONESE'S WEDDING FEAST Peter Bossano 1.And the third day there was a marriage in Cana of Galilee; and the mother of Jesus was there: 2. And both Jesus was called, and his disciples, to the marriage. 3. And when they wanted wine, the mother of Jesus saith unto him, They have no wine. 4. Jesus saith unto her, Woman what have I to do with thee? mine hour is not yet come. 5. His mother saith unto the servants, Whatsoever he saith unto you, do it. 6. And there were set there six waterpots of stone, after the manner of the purifying of the Jews, containing two or three firkins apiece. 7. Jesus saith unto them, Fill the waterpots with water. And they filled them up to the brim. 8. And he saith unto them, Draw out now, and bear unto the governor of the feast. And they bare it. 9. When the ruler of the feast had tasted the water that was made wine, and knew not whence it was: (but the servants which drew the water knew;) the governor of the feast called the bridegroom, 10.And saith unto him, Every man at the beginning doth set forth good wine; and when men have well drunk, then that which is worst; but thou hast kept the good wine until now. —John 2: 1-10 (KingJames Version) In Paolo Veronese's painting of the Wedding Feast at Cana, as in St. John's version of this story, not everything is as at seems. -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

The Modal Gamut in the Sixteenth Century

Page 61 C H A P T E R 3 The Modal Gamut in the Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries I. Introductory Remarks In this chapter we will trace the origins of eleven pitch-class tonality in the modally inflected music of the sixteenth century, particularly in the works of the Mannerist composers, beginning with Cipriano de Rore, through to the works of Orlando de Lasso.1 These composers consciously sought to express ever more highly emotional poetry (both secular and sacred) through their interpretation of the Greek diatonic and chromatic genera. The chapter then continues with a detailed discussion of selected madrigals by Claudio Monteverdi, whose music is emblematic of the evolving modal language of the early to middle seventeenth century 1Parts of this chapter were previously published in: Henry Burnett, “A New Theory of Hexachord Modulation in the Late Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries,” International Journal of Musicology, 8/1999,115-175. However, since writing that article, we find that our interpretation of the music in relation to our theory has changed drastically. Therefore this present chapter supercedes all analytical discussions contained in the previous article. Page 62 The inexhaustible diversity and richness of the harmonic style that typifies the music of these influential composers, and that of the early to middle seventeenth century in general, would seem to militate against the formation of a unified theory appropriate to this music. Part of the problem lies in the very nature of the music itself, which seems, on the surface at least, to be forever fluctuating between a chromatically extended modal system and an emerging “key-centered” diatonic one; the two systems often, even deliberately, work in opposition, even within the same composition. -

Emotion and Vocal Emulation in Trumpet Performance and Pedagogy

Sounding the Inner Voice: Emotion and Vocal Emulation in Trumpet Performance and Pedagogy by Geoffrey Tiller A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Faculty of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Geoffrey Tiller 2015 Sounding the Inner Voice: Emotion and Vocal Emulation in Trumpet Performance and Pedagogy Geoffrey Tiller Doctor of Musical Arts Faculty of Music University of Toronto 2015 Abstract This dissertation examines the aesthetics of trumpet performance with a focus on the relationship between a vocal approach and expressiveness in trumpet playing. It aims to improve current trumpet pedagogy by presenting different strategies for developing a theory of a vocal approach. Many of the concepts and anecdotes used in respected pedagogical publications and by trumpet teachers themselves are heavily influenced by the premise that emulating the voice is a desired outcome for the serious trumpet performer. Despite the abundance of references to the importance of playing trumpet with a vocal approach, there has been little formal inquiry into this subject and there is a need for more informed teaching strategies aimed at clarifying the concepts of vocal emulation. The study begins with an examination of vocal performance and pedagogy in order to provide an understanding of how emulating the voice came to be so central to contemporary notions of trumpet performance aesthetics in Western concert music. ii Chapter Two explores how emotion has been theorized in Western art music and the role that the human voice is thought to play in conveying such emotion. I then build on these ideas to theorize how music and emotion might be better understood from the performer’s perspective. -

Natural Trumpet Music and the Modern Performer A

NATURAL TRUMPET MUSIC AND THE MODERN PERFORMER A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Laura Bloss December, 2012 NATURAL TRUMPET MUSIC AND THE MODERN PERFORMER Laura Bloss Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________ _________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Chand Midha _________________________ _________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. Scott Johnston Dr. George R. Newkome _________________________ _________________________ School Director Date Dr. Ann Usher ii ABSTRACT The Baroque Era can be considered the “golden age” of trumpet playing in Western Music. Recently, there has been a revival of interest in Baroque trumpet works, and while the research has grown accordingly, the implications of that research require further examination. Musicians need to be able to give this factual evidence a context, one that is both modern and historical. The treatises of Cesare Bendinelli, Girolamo Fantini, and J.E. Altenburg are valuable records that provide insight into the early development of the trumpet. There are also several important modern resources, most notably by Don Smithers and Edward Tarr, which discuss the historical development of the trumpet. One obstacle for modern players is that the works of the Baroque Era were originally played on natural trumpet, an instrument that is now considered a specialty rather than the standard. Trumpet players must thus find ways to reconcile the inherent differences between Baroque and current approaches to playing by combining research from early treatises, important trumpet publications, and technical and philosophical input from performance practice essays.