A Pedal Study of Johann Sebastian Bach's Orgelbüchlein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ORGAN WORKS of HEALEY WILLAN THESIS Presented to The

{ to,26?5 THE ORGAN WORKS OF HEALEY WILLAN THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Music By Robert L. Massingham, B. S., M. S. Denton, Texas August, 1957 PREFACE LHealey Willan occupies an unique position in Canadian Music and can be considered as that nation's "elder musical statesman." At the time of writing he is a septuagenarian and still very much active in his profession. Born and trained in England, he was well-established there when he was persuaded to come to Toronto, Canada, in 1913 at the age of thirty-three. Since that time he has contributed enor- iously to the growth of music in his adopted country, carry- ing on the traditions of his fine English background in music while encouraging the development of native individuality in Canadian music. Iillan has been first and foremost a musician of the church--an organist and choirmaster--a proud field which can boast many an eminent name in music including that of J. S. Bach. Willan's creativity in music has flowered in many other directions--as a distinguished teacher, as a lecturer and recitalist, and as a composer. He has written in all forms and for all instruments, but his greatest renown, at any rate in the TUnited States, is for his organ and choral works. The latter constitute his largest single body of compositions by numerical count of titles, and his organ works are in a close second place. iii Willants Introduction, Passaqaglia, and Fuue has been well-known for decades as one of the finest compositions in organ literature, enjoying a position alongside the organ works of Liszt, Yranck, and Reubke. -

Music for the Christmas Season by Buxtehude and Friends Musicmusic for for the the Christmas Christmas Season Byby Buxtehude Buxtehude and and Friends Friends

Music for the Christmas season by Buxtehude and friends MusicMusic for for the the Christmas Christmas season byby Buxtehude Buxtehude and and friends friends Else Torp, soprano ET Kate Browton, soprano KB Kristin Mulders, mezzo-soprano KM Mark Chambers, countertenor MC Johan Linderoth, tenor JL Paul Bentley-Angell, tenor PB Jakob Bloch Jespersen, bass JB Steffen Bruun, bass SB Fredrik From, violin Jesenka Balic Zunic, violin Kanerva Juutilainen, viola Judith-Maria Blomsterberg, cello Mattias Frostenson, violone Jane Gower, bassoon Allan Rasmussen, organ Dacapo is supported by the Cover: Fresco from Elmelunde Church, Møn, Denmark. The Twelfth Night scene, painted by the Elmelunde Master around 1500. The Wise Men presenting gifts to the infant Jesus.. THE ANNUNCIATION & ADVENT THE NATIVITY Heinrich Scheidemann (c. 1595–1663) – Preambulum in F major ������������1:25 Dietrich Buxtehude – Das neugeborne Kindelein ������������������������������������6:24 organ solo (chamber organ) ET, MC, PB, JB | violins, viola, bassoon, violone and organ Christian Geist (c. 1640–1711) – Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern ������5:35 Franz Tunder (1614–1667) – Ein kleines Kindelein ��������������������������������������4:09 ET | violins, cello and organ KB | violins, viola, cello, violone and organ Johann Christoph Bach (1642–1703) – Merk auf, mein Herz. 10:07 Dietrich Buxtehude – In dulci jubilo ����������������������������������������������������������5:50 ET, MC, JL, JB (Coro I) ET, MC, JB | violins, cello and organ KB, KM, PB, SB (Coro II) | cello, bassoon, violone and organ Heinrich Scheidemann – Preambulum in D minor. .3:38 Dietrich Buxtehude (c. 1637-1707) – Nun komm der Heiden Heiland. .1:53 organ solo (chamber organ) organ solo (main organ) NEW YEAR, EPIPHANY & ANNUNCIATION THE SHEPHERDS Dietrich Buxtehude – Jesu dulcis memoria ����������������������������������������������8:27 Dietrich Buxtehude – Fürchtet euch nicht. -

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Orgelbü�Chlein

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Orgelbüchlein JOAN LIPPINCOTT , ORGAN JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Orgelbüchlein J O A N L I P P I N C O T T , O R G A N 1. | Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 599 01:31 23. | Da Jesus an dem Kreuze stund, BWV 621 01:20 2. | Gott, durch deine Güte, 24. | O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde gross, BWV 622 05:28 or Gottes Sohn ist kommen, BWV 600 01:13 25. | Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ, BWV 623 01:01 3. | Herr Christ, der ein’ge Gottessohn, 26. | Hilf, Gott, dass mir’s gelinge, BWV 624 01:22 or Herr Gott, nun sei gepreist, BWV 601 01:42 27. | Christ lag in Todesbanden, BWV 625 01:32 4. | Lob sei dem allmächtigen Gott, BWV 602 00:55 28. | Jesus Christus, unser Heiland, BWV 626 00:54 5. | Puer natus in Bethlehem, BWV 603 00:59 29. | Christ ist erstanden, BWV 627 04:21 6. | Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ, BWV 604 01:28 30. | Erstanden ist der heil'ge Christ, BWV 628 00:51 7. | Der Tag, der ist so freudenreich, BWV 605 02:01 31. | Erschienen ist der herrliche Tag, BWV 629 01:04 8. | Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her, BWV 606 00:46 32. | Heut triumphieret Gottes Sohn, BWV 630 01:27 9. | Vom Himmel kam der Engel Schar, BWV 607 01:23 33. | Komm, Gott Schöpfer, Heiliger Geist, BWV 631 00:59 10. | In dulci jubilo, BWV 608 01:31 34. | Herr Jesu Christ, dich zu uns wend, BWV 632 01:31 11. -

![Fasolis-D-V06c[Brilliant-2CD-Booklet].Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6826/fasolis-d-v06c-brilliant-2cd-booklet-pdf-86826.webp)

Fasolis-D-V06c[Brilliant-2CD-Booklet].Pdf

94639 bach_BL2 v8_BRILLIANT 04/02/2013 10:10 Page 2 Johann Sebastian Bach 1685 –1750 Passion Chorales 39 –40 O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig BWV618 3’54 1’24 Orgelbüchlein BWV 599 –644 41 –42 Christe, du Lamm Gottes BWV619 1’01 1’23 with alternating chorales 43 –44 Christus, der uns selig macht BWV620 2’45 1’22 45 –46 Da Jesus an dem Kreuze stund BWV621 2’03 1’10 Compact Disc 1 67’20 Compact Disc 2 67’14 Part I Organ Chorale Advent Chorales Part II Organ Chorale 1–2 Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland BWV599 2’03 0’46 1–2 O Mensch, bewein dein’ Sünde groß BWV622 6’02 2’27 3–4 Gottes Sohn ist kommen BWV600 1’27 1’10 3–4 Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ BWV623 1’03 0’49 5–6 Herr Christ, der ein’ge Gottes Sohn BWV601 1’38 1’09 5–6 Hilf Gott, daß mir’s gelinge BWV624 1’33 1’01 7–8 Lob sei dem allmächtigen Gott BWV602 0’54 0’47 Easter Chorales Christmas Chorales 7–8 Christ lag in Todesbanden BWV625 1’19 1’25 9–10 Puer natus in Bethlehem BWV603 1’18 0’46 9–10 Jesus Christus, unser Heiland BWV626 1’01 0’49 11 –12 Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ BWV604 1’12 0’48 11 –12 Christ ist erstanden Verse 1 BWV627 1’18 0’50 13 –14 Der Tag, der ist so freudenreich BWV605 1’57 1’18 13 –14 Christ ist erstanden Verse 2 1’14 0’50 15 –16 Vom Himmel hoch, da komm’ ich her BWV606 0’54 0’47 15 –16 Christ ist erstanden Verse 3 1’41 0’49 17 –18 Vom Himmel kam der Engel Schar BWV607 1’10 0’30 17 –18 Erstanden ist der heil’ge Christ BWV628 0’44 0’26 19 –20 In dulci jubilo BWV608 1’24 0’51 19 –20 Erschienen ist der herrlich Tag BWV629 0’50 0’36 21 –22 Lobt Gott, ihr Christen, allzugleich -

Halle, the City of Music a Journey Through the History of Music

HALLE, THE CITY OF MUSIC A JOURNEY THROUGH THE HISTORY OF MUSIC 8 WC 9 Wardrobe Ticket office Tour 1 2 7 6 5 4 3 EXHIBITION IN WILHELM FRIEDEMANN BACH HOUSE Wilhelm Friedemann Bach House at Grosse Klausstrasse 12 is one of the most important Renaissance houses in the city of Halle and was formerly the place of residence of Johann Sebastian Bach’s eldest son. An extension built in 1835 houses on its first floor an exhibition which is well worth a visit: “Halle, the City of Music”. 1 Halle, the City of Music 5 Johann Friedrich Reichardt and Carl Loewe Halle has a rich musical history, traces of which are still Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752–1814) is known as a partially visible today. Minnesingers and wandering musicographer, composer and the publisher of numerous musicians visited Giebichenstein Castle back in the lieder. He moved to Giebichenstein near Halle in 1794. Middle Ages. The Moritzburg and later the Neue On his estate, which was viewed as the centre of Residenz court under Cardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg Romanticism, he received numerous famous figures reached its heyday during the Renaissance. The city’s including Ludwig Tieck, Clemens Brentano, Novalis, three ancient churches – Marktkirche, St. Ulrich and St. Joseph von Eichendorff and Johann Wolfgang von Moritz – have always played an important role in Goethe. He organised musical performances at his home musical culture. Germany’s oldest boys’ choir, the in which his musically gifted daughters and the young Stadtsingechor, sang here. With the founding of Halle Carl Loewe took part. University in 1694, the middle classes began to develop Carl Loewe (1796–1869), born in Löbejün, spent his and with them, a middle-class musical culture. -

Xvii. Tempo En Fermates Bij De Uitvoering Van Koralen in Bachs Cantates En Passies

XVII. TEMPO EN FERMATES BIJ DE UITVOERING VAN KORALEN IN BACHS CANTATES EN PASSIES In dit hoofdstuk staan het tempo van de koralen en de wijze waarop de fermates werden uitgevoerd centraal. Zoals bekend zijn koralen door de gemeente gezongen gezangen tijdens erediensten. In Bachs tijd stonden de tekst en soms ook de melodie hiervan in de gebruikte gezangboeken. De gezangen waren over het algemeen bij de gemeente bekend. Onder kora- len zullen tevens verstaan worden de – meestal vierstemmig homofoon gezette – gezangen, zoals die in Bachs cantates en passies veel voorkomen: zij hadden immers dezelfde tekst en melodie als de gemeentegezangen. Ook wanneer instrumenten een zelfstandige rol hadden, in de vorm van tussenspelen (bijvoorbeeld in het slotkoraal ‘Jesus bleibet meine Freude‘ BWV 147/10) of extra partijen (‘Weil du vom Tod erstanden bist' BWV 95/7), worden ze hier gerekend tot Bachs koralen. Deze studie richt zich niet primair op koraalmelodieën die – meestal éénstemmig – als cantus firmus gezongen of gespeeld worden tijdens een aria of reci- tatief, maar het ligt voor de hand dat de beschreven conclusies hierbij ook van toepassing zijn. In de eerste paragraaf wordt gekeken naar de ontwikkeling van de gemeentezang in Duits- land, en hoe die op orgel begeleid werd. Vervolgens wordt onderzocht hoe er in traktaten over het tempo van de gemeentezang werd gesproken. Daarna worden de resultaten geëx- trapoleerd naar de hoofdkerken in Leipzig onder Johann Sebastian Bach. Het moge zo zijn dat de koralen als gemeentezang langzaam werden uitgevoerd, maar gold dat ook voor de koralen in Bachs cantates? In deze paragraaf wordt getracht een antwoord te vinden op deze vraag. -

Michael Praetorius's Theology of Music in Syntagma Musicum I (1615): a Politically and Confessionally Motivated Defense of Instruments in the Lutheran Liturgy

MICHAEL PRAETORIUS'S THEOLOGY OF MUSIC IN SYNTAGMA MUSICUM I (1615): A POLITICALLY AND CONFESSIONALLY MOTIVATED DEFENSE OF INSTRUMENTS IN THE LUTHERAN LITURGY Zachary Alley A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2014 Committee: Arne Spohr, Advisor Mary Natvig ii ABSTRACT Arne Spohr, Advisor The use of instruments in the liturgy was a controversial issue in the early church and remained at the center of debate during the Reformation. Michael Praetorius (1571-1621), a Lutheran composer under the employment of Duke Heinrich Julius of Braunschweig-Lüneburg, made the most significant contribution to this perpetual debate in publishing Syntagma musicum I—more substantial than any Protestant theologian including Martin Luther. Praetorius's theological discussion is based on scripture, the discourse of early church fathers, and Lutheran theology in defending the liturgy, especially the use of instruments in Syntagma musicum I. In light of the political and religious instability throughout Europe it is clear that Syntagma musicum I was also a response—or even a potential solution—to political circumstances, both locally and in the Holy Roman Empire. In the context of the strengthening counter-reformed Catholic Church in the late sixteenth century, Lutheran territories sought support from Reformed church territories (i.e., Calvinists). This led some Lutheran princes to gradually grow more sympathetic to Calvinism or, in some cases, officially shift confessional systems. In Syntagma musicum I Praetorius called on Lutheran leaders—prince-bishops named in the dedication by territory— specifically several North German territories including Brandenburg and the home of his employer in Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel, to maintain Luther's reforms and defend the church they were entrusted to protect, reminding them that their salvation was at stake. -

The Atlanta Music Scene • WABE FM 90.1 Broadcast Schedule - July 2021 Host: Robert Hubert Producer: Tommy Joe Anderson

The Atlanta Music Scene • WABE FM 90.1 Broadcast Schedule - July 2021 Host: Robert Hubert Producer: Tommy Joe Anderson Sundays at 10 P.M. at FM 90.1 Over-the-air & LIVE STREAM at wabe.org Tuesdays at 3 p.m. & Saturdays at 10 a.m. at 90.1-2 on WABE’s Classics Stream on your HD Radio, Internet Radio or online at WABE.org and with the WABE Mobile App available for free download at WABE.org Underwriting of the Atlanta Music Scene is provided by ACA Digital Recording with additional support from Robert Hubert. July 4, 2021 – 8:00pm - 10:00pm On Air Broadcast Preempted by “A Capitol Fourth” A Capitol Fourth is an annual July 4th tradition with a live concert direct from the steps of the U.S. Capitol. NPR is pleased to offer this special for broadcast again this year. Emanuel Ax, piano [HD-2 and Online Broadcasts as scheduled Tuesday, July 6 @ 3:00pm & Saturday July 10 @ 10:00am Johannes Brahms: Two Rhapsodies, Op. 79 George Benjamin: Piano Figures Frédéric Chopin: Three Mazurkas, Op. 50 Chopin: Nocturnes, Op. 62 No. 1 in B Major and Op. 15, No. 2 in F-Sharp Major Chopin: Andante spianato et Grande Polonaise brillante in E-Flat Major, Op. 22 [Recorded at Clayton State University’s Spivey Hall 03/24/2019] Program Time 01:06:42 July 11, 2021 – 10:00pm Paul Halley, organ J.S. Bach: Chorale Prelude on “In Dulci Jubilo” Maurice Dupre: Choral “In Dulci Jubilo” Paul Halley: Improvisation on “Good Christian Folk Rejoice” J. -

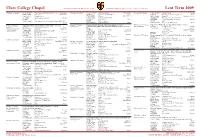

C7054 Clare College Term Card:Layout 1

Clare College Chapel TUESDAYS AND THURSDAYS 6.15 p.m. SUNDAYS 6.00 p.m. (preceded by a recital at 5.30 p.m.) Lent Term 2009. Thursday 15 January VOLUNTARY Puer natus in Bethlehem, BuxWV 217 Buxtehude Thursday 5 February VOLUNTARY Canzona Quinta Frescobaldi Tuesday 24 February VOLUNTARY Sursum Corda Ireland RESPONSES Ayleward PSALM 61 INTROIT Ich bin’s, ich sollte büssen Bach INTROIT Bin ich gleich von dir gewichen Bach CANTICLES Walmisley in d RESPONSES Clucas PSALM 27 RESPONSES Radcliffe PSALM 119: 1–8 ANTHEM Quem vidistis, pastores Dering CANTICLES Causton Fauxbourdon CANTICLES Wood in F (Collegium Regale) HYMN 47 ANTHEM If ye love me Tallis ANTHEM O God, thou hast cast us out Purcell VOLUNTARY Vom Himmel Hoch, da Komm ich her, BWV 606 HYMN 383 (vv. 1, 2, 4) HYMN 404 Bach VOLUNTARY Veni Redemptor Tallis VOLUNTARY Fugue in C, BVW 545/ii Bach Wednesday 25 February Vigil for Ash Wednesday & Imposition of Ashes 10.00 p.m. Sunday 18 January Organ Recital by Simon Thomas Jacobs (Clare) 5.30 p.m. Sunday 8 February Piano Recital by Alexander Bryson (London) 5.30 p.m. Septuagesima Joint Evensong with Universitätschor Innsbruck, Director Georg Ash Wednesday PSALM 51 (Miserere) Allegri Epiphany 2 INTROIT In the bleak midwinter Darke Weiss ANTHEMS O saviour of the world Howells (Week of Prayer for RESPONSES Ayleward PSALM 96 INTROIT Here is the little door Howells O vos omnes Vaughan Williams Christian Unity) CANTICLES Plainsong (Tonus Peregrinus/IIi) RESPONSES Smith PSALM 5 Save me, O God Lavino ANTHEM Magnificat II Swayne CANTICLES Stanford in -

Saint Joseph Cathedral Music

2.21.16 Lent II-C 3.25.16 Good Friday of the Lord’s Passion Introit Dominus secus [I] Froberger Fantasia in A-minor Victoria/Rowan St. John Passion Choruses Offertorium Sicut in holocausto [V] Frescobaldi Ricercare on the Third Tone Clemens non Papa Crux fidelis Communio Simon Ioannis [IV] Bach Prelude in B-minor, BWV 869a Shaw/Parker Wondrous Love Bulgarian Chant When they who with Mary came Near Audi, benigne Conditor (Chantworks) Bruckner Christus factus est 5.8.16 Solemnity of the Ascension of the Lord Introit Tibi dixit cor meum [III] Sanders The Reproaches Bach Prelude in D-Major, BWV 532a Communio Visionem quam vidistis [I] 3.25.16 The Office of Tenebrae Messiaen I. Majesté du Christ demandant sa gloire à son Père Lassus Tristis est anima mea Tallis Lamentations of Jeremiah (L’Ascension) Lauridsen O nata lux Lassus Caligaverunt oculi mei Messiaen IV. Prière du Christ montant vers son Père (L’Ascension) 2.28.16 Lent III-C Casals O vos omnes Leighton Fanfare Langlais Priére; Prélude modal Victoria Nunc dimittis Introit Viri Galilaei [VII] Bach Three Preludes on the Kyrie, BWV 672-74 Allegri Miserere Communio Psallite Domino [I] Bach O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde gross, BWV 622 Croft God Is Gone Up 3.26.16 Easter Vigil/Easter Day Sweelinck Echo Fantasia [Dorian] Verdi Ave Maria (Four Sacred Pieces) Böhm Christ lag in Todesbanden Introit Oculi mei [VII] Buxtehude Prelude, Fugue, and Ciacona in C Major, BuxWV 138 5.15.16 Solemnity of Pentecost Communio Passer invenit [I] Dupré Fugue on an Easter Alleluia, op. -

2007-08 Repertoire

Cathedral Gallery Singers and Diocesan Chorale 2007-2008 Choral Repertoire Cathedral of Saint Joseph the Workman La Crosse, Wisconsin Brian Luckner, DMA Director of Music and Organist September 16 Twenty–fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time November 11 Thirty–second Sunday in Ordinary Time Have Mercy on Me Thomas Tomkins Alleluia. May Flights of Angels Sing John Tavener 1573–1656 Thee to Thy rest b. 1944 Cantate Domino Hans Leo Hassler Justorum animae William Byrd 1564–1612 1543–1623 September 23 Twenty–fifth Sunday in Ordinary Time November 18 Thirty–third Sunday in Ordinary Time Give Almes of Thy Goods Christopher Tye Psalm 121 (Requiem, Movt. IV) Herbert Howells c. 1505–c. 1572 1892–1983 Sicut cervus Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina I Heard a Voice from Heaven (Requiem, Movt. VI) Herbert Howells c. 1525–1594 1892–1983 September 30 Twenty–sixth Sunday in Ordinary Time November 25 Christ the King Lead Me, Lord Samuel Sebastian Wesley Dignus est Agnus, qui occisus est (Introit) Gregorian Chant 1810–1876 Ave verum corpus Gerald Near I Was Glad Frank Ferko b. 1942 b. 1950 King of Glory, King of Peace Eric H. Thiman October 7 Twenty–seventh Sunday in Ordinary Time 1900–1975 Lass dich nur nichts nicht dauren Johannes Brahms December 2 First Sunday of Advent 1833–1897 Come, Let’s Rejoice John Amner Ad te levavi animam meam (Introit) Gregorian Chant 1579–1641 O Pray for the Peace of Jerusalem Thomas Tomkins October 14 Twenty–eighth Sunday in Ordinary Time 1572–1656 Veni Redemptor gentium Jacob Handl Ave Maria (Op. 23, No. -

Keyboard & Instrumental

Keyboard & Instrumental GIA PUBLICATIONS, INC. New THRee PSALM PRELUDES FOR ORGAN Raymond Haan This set of three preludes is based on psalm texts—“Repose” based on Psalm 4:8, “Contemplation” based on Psalm 8:3a, 4a, and “Meditation” based on Psalm 143:5. The pieces can be used as a set or as individual move- ments. Extensive registration suggestions and nuance of dynamics are included. Contents: Repose • Contemplation • Meditation G-8088 ......................................................................... $12.00 LORD, I WANT TO BE A CHRISTIAN FOR ORGAN AND FLUTE arr. Kenneth Dake Kenneth Dake’s arrangement for flute and organ is based on the familiar African American spiritual “Lord, I Want to Be a Christian.” This charming piece is highly accessible for both parts and offers endless expressive possibilities for interpretation. Perfect for a brief moment of reflection and meditation. G-8184 ......................................................................... $10.00 RESIGNATION MY ShePheRD WILL SUPPLY MY NeeD FOR ORGAN AND VIOLA OR HORN IN F arr. Kenneth Dake Originally written for well-known violist Lawrence Dutton, this beautiful arrangement for viola and organ meanders gently as if floating on a soft summer breeze. The peaceful repose of this work makes it perfect for any reflective moment in your worship service. A part for horn in F is also provided. G-8185 .......................................................................... $12.00 HIS EYE IS ON The SPARROW FOR ORGAN AND HORN IN F OR CLARINET IN B< Charles H. Gabriel arr. Kenneth Dake This meditative piece based on Matthew 6:26 and John 14:1, 27 employs the tender hymn tune sparrow. Scored for horn in F and organ, both parts begin in a quiet, thoughtful manner before soaring to a majestic climax and then returning to the opening mood.