The Lost Chord Part

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Orgelbü�Chlein

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Orgelbüchlein JOAN LIPPINCOTT , ORGAN JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Orgelbüchlein J O A N L I P P I N C O T T , O R G A N 1. | Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 599 01:31 23. | Da Jesus an dem Kreuze stund, BWV 621 01:20 2. | Gott, durch deine Güte, 24. | O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde gross, BWV 622 05:28 or Gottes Sohn ist kommen, BWV 600 01:13 25. | Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ, BWV 623 01:01 3. | Herr Christ, der ein’ge Gottessohn, 26. | Hilf, Gott, dass mir’s gelinge, BWV 624 01:22 or Herr Gott, nun sei gepreist, BWV 601 01:42 27. | Christ lag in Todesbanden, BWV 625 01:32 4. | Lob sei dem allmächtigen Gott, BWV 602 00:55 28. | Jesus Christus, unser Heiland, BWV 626 00:54 5. | Puer natus in Bethlehem, BWV 603 00:59 29. | Christ ist erstanden, BWV 627 04:21 6. | Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ, BWV 604 01:28 30. | Erstanden ist der heil'ge Christ, BWV 628 00:51 7. | Der Tag, der ist so freudenreich, BWV 605 02:01 31. | Erschienen ist der herrliche Tag, BWV 629 01:04 8. | Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her, BWV 606 00:46 32. | Heut triumphieret Gottes Sohn, BWV 630 01:27 9. | Vom Himmel kam der Engel Schar, BWV 607 01:23 33. | Komm, Gott Schöpfer, Heiliger Geist, BWV 631 00:59 10. | In dulci jubilo, BWV 608 01:31 34. | Herr Jesu Christ, dich zu uns wend, BWV 632 01:31 11. -

![Fasolis-D-V06c[Brilliant-2CD-Booklet].Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6826/fasolis-d-v06c-brilliant-2cd-booklet-pdf-86826.webp)

Fasolis-D-V06c[Brilliant-2CD-Booklet].Pdf

94639 bach_BL2 v8_BRILLIANT 04/02/2013 10:10 Page 2 Johann Sebastian Bach 1685 –1750 Passion Chorales 39 –40 O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig BWV618 3’54 1’24 Orgelbüchlein BWV 599 –644 41 –42 Christe, du Lamm Gottes BWV619 1’01 1’23 with alternating chorales 43 –44 Christus, der uns selig macht BWV620 2’45 1’22 45 –46 Da Jesus an dem Kreuze stund BWV621 2’03 1’10 Compact Disc 1 67’20 Compact Disc 2 67’14 Part I Organ Chorale Advent Chorales Part II Organ Chorale 1–2 Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland BWV599 2’03 0’46 1–2 O Mensch, bewein dein’ Sünde groß BWV622 6’02 2’27 3–4 Gottes Sohn ist kommen BWV600 1’27 1’10 3–4 Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ BWV623 1’03 0’49 5–6 Herr Christ, der ein’ge Gottes Sohn BWV601 1’38 1’09 5–6 Hilf Gott, daß mir’s gelinge BWV624 1’33 1’01 7–8 Lob sei dem allmächtigen Gott BWV602 0’54 0’47 Easter Chorales Christmas Chorales 7–8 Christ lag in Todesbanden BWV625 1’19 1’25 9–10 Puer natus in Bethlehem BWV603 1’18 0’46 9–10 Jesus Christus, unser Heiland BWV626 1’01 0’49 11 –12 Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ BWV604 1’12 0’48 11 –12 Christ ist erstanden Verse 1 BWV627 1’18 0’50 13 –14 Der Tag, der ist so freudenreich BWV605 1’57 1’18 13 –14 Christ ist erstanden Verse 2 1’14 0’50 15 –16 Vom Himmel hoch, da komm’ ich her BWV606 0’54 0’47 15 –16 Christ ist erstanden Verse 3 1’41 0’49 17 –18 Vom Himmel kam der Engel Schar BWV607 1’10 0’30 17 –18 Erstanden ist der heil’ge Christ BWV628 0’44 0’26 19 –20 In dulci jubilo BWV608 1’24 0’51 19 –20 Erschienen ist der herrlich Tag BWV629 0’50 0’36 21 –22 Lobt Gott, ihr Christen, allzugleich -

Xvii. Tempo En Fermates Bij De Uitvoering Van Koralen in Bachs Cantates En Passies

XVII. TEMPO EN FERMATES BIJ DE UITVOERING VAN KORALEN IN BACHS CANTATES EN PASSIES In dit hoofdstuk staan het tempo van de koralen en de wijze waarop de fermates werden uitgevoerd centraal. Zoals bekend zijn koralen door de gemeente gezongen gezangen tijdens erediensten. In Bachs tijd stonden de tekst en soms ook de melodie hiervan in de gebruikte gezangboeken. De gezangen waren over het algemeen bij de gemeente bekend. Onder kora- len zullen tevens verstaan worden de – meestal vierstemmig homofoon gezette – gezangen, zoals die in Bachs cantates en passies veel voorkomen: zij hadden immers dezelfde tekst en melodie als de gemeentegezangen. Ook wanneer instrumenten een zelfstandige rol hadden, in de vorm van tussenspelen (bijvoorbeeld in het slotkoraal ‘Jesus bleibet meine Freude‘ BWV 147/10) of extra partijen (‘Weil du vom Tod erstanden bist' BWV 95/7), worden ze hier gerekend tot Bachs koralen. Deze studie richt zich niet primair op koraalmelodieën die – meestal éénstemmig – als cantus firmus gezongen of gespeeld worden tijdens een aria of reci- tatief, maar het ligt voor de hand dat de beschreven conclusies hierbij ook van toepassing zijn. In de eerste paragraaf wordt gekeken naar de ontwikkeling van de gemeentezang in Duits- land, en hoe die op orgel begeleid werd. Vervolgens wordt onderzocht hoe er in traktaten over het tempo van de gemeentezang werd gesproken. Daarna worden de resultaten geëx- trapoleerd naar de hoofdkerken in Leipzig onder Johann Sebastian Bach. Het moge zo zijn dat de koralen als gemeentezang langzaam werden uitgevoerd, maar gold dat ook voor de koralen in Bachs cantates? In deze paragraaf wordt getracht een antwoord te vinden op deze vraag. -

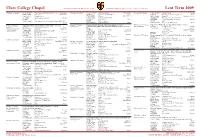

C7054 Clare College Term Card:Layout 1

Clare College Chapel TUESDAYS AND THURSDAYS 6.15 p.m. SUNDAYS 6.00 p.m. (preceded by a recital at 5.30 p.m.) Lent Term 2009. Thursday 15 January VOLUNTARY Puer natus in Bethlehem, BuxWV 217 Buxtehude Thursday 5 February VOLUNTARY Canzona Quinta Frescobaldi Tuesday 24 February VOLUNTARY Sursum Corda Ireland RESPONSES Ayleward PSALM 61 INTROIT Ich bin’s, ich sollte büssen Bach INTROIT Bin ich gleich von dir gewichen Bach CANTICLES Walmisley in d RESPONSES Clucas PSALM 27 RESPONSES Radcliffe PSALM 119: 1–8 ANTHEM Quem vidistis, pastores Dering CANTICLES Causton Fauxbourdon CANTICLES Wood in F (Collegium Regale) HYMN 47 ANTHEM If ye love me Tallis ANTHEM O God, thou hast cast us out Purcell VOLUNTARY Vom Himmel Hoch, da Komm ich her, BWV 606 HYMN 383 (vv. 1, 2, 4) HYMN 404 Bach VOLUNTARY Veni Redemptor Tallis VOLUNTARY Fugue in C, BVW 545/ii Bach Wednesday 25 February Vigil for Ash Wednesday & Imposition of Ashes 10.00 p.m. Sunday 18 January Organ Recital by Simon Thomas Jacobs (Clare) 5.30 p.m. Sunday 8 February Piano Recital by Alexander Bryson (London) 5.30 p.m. Septuagesima Joint Evensong with Universitätschor Innsbruck, Director Georg Ash Wednesday PSALM 51 (Miserere) Allegri Epiphany 2 INTROIT In the bleak midwinter Darke Weiss ANTHEMS O saviour of the world Howells (Week of Prayer for RESPONSES Ayleward PSALM 96 INTROIT Here is the little door Howells O vos omnes Vaughan Williams Christian Unity) CANTICLES Plainsong (Tonus Peregrinus/IIi) RESPONSES Smith PSALM 5 Save me, O God Lavino ANTHEM Magnificat II Swayne CANTICLES Stanford in -

Lutheran Layout II

What’s New Welcome to Our Catalog Marty Haugen . .4-5 John Ferguson . .6 Taizé . .7 Liturgies . .8-9 New Releases for a New Millennium from GIA Herman Stuempfle books . .10 Hymn Resources . .11 A glorious choral festival as Instrumental Music . .12 only John Ferguson can create Order Form . .13 with the St. Olaf Cantorei... Choral Music . .14-18 Organ/Piano Music . .19 A Thousand Ages: A Celebration of Hope...page 6 Psalms . .20 Ars Antiqua Choralis . .21 Part of the Soli Deo Gloria Iona . .22 Collection... Reprint License . .23 Come Let Us Sing for Joy: A Morning Prayer Service and To our Lutheran customers: Beneath the Tree of Life, an In October 1999, the historic signing of the Concordat between the ecumenical communion service Roman Catholic Church and several Lutheran church bodies reminded us by Marty Haugen...pp. 4-5 again of the common heritage which many denominations share, and of the desire to work toward even greater cooperation in the future.Today, as For worship leaders, in the past, it seems as though the church is always undergoing a process composers...anyone looking of reformation. The past twenty-five years have seen many worshiping for inspirational texts... communities search for meaningful and useful ways to worship. The task of doing worship has never been more challenging or more interesting Awake Our Hearts to Praise! than it is today. The Hymns of Herman GIA offers an incredible diversity of resources for worship and Stuempfle...page 10 music—from choral works of the old masters to modern settings of the psalms, from Gregorian chant to contemporary instrumental works, from Take a look at our choral and hymn concertato settings to gospel-style music. -

A Pedal Study of Johann Sebastian Bach's Orgelbüchlein

A Pedal Study of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Orgelbüchlein A document proposal submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Keyboard Division of the College-Conservatory of Music April, 2013 by Yoonnah L. Lee BM, Ewha Womans University, Korea, 2002 MM, University of Cincinnati, 2005 Committee Chair: Roberta Gary, DMA ABSTRACT This study explores diverse figures in the pedal passages in Johann Sebastian Bach’s Orgelbüchlein in order to improve pedal technique by a more effective practice style. The Orgelbüchlein has been thought to include easy pieces that are usually played by beginning students. One of the reasons for this belief is that the pieces are short. In fact, however, none of the chorale settings in the Orgelbüchlein are easy to play. Their various levels of difficulty and styles prove Bach’s pedagogical purpose. I will take full advantage of the obbligato pedal writing in the Orgelbüchlein to develop a pedal technique for music composed before 1750. This study provides pedal exercises according to level of difficulty with directions for practicing included. These pedal exercises based on the Orgelbüchlein will challenge organ students in the great variety they include. ii Copyright © 2013 by Yoonnah L. Lee. All rights reserverd. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My long journey of graduate studies at CCM would not have been possible without the support of many people. I would like to acknowledge my advisor, Dr. Roberta Gary. Her teaching and mentorship throughout the completion of my studies will always be remembered with a profound gratitude. -

Bach: Magnificat & Christmas Cantata

DUNEDIN CONSORT JOHN BUTT CHRISTMAS CANTATA 63 Reconstruction of Bach’s first Christmas Vespers in Leipzig in E flat major, BWV 243a and Cantata, BWV 63, within a reconstruction of J.S. Bach’s first Christmas in Leipzig: Vespers in the Nikolaikirche, 25 December 1723 Dunedin Consort John Butt Julia Doyle soprano Joanne Lunn soprano Clare Wilkinson mezzo-soprano Nicholas Mulroy tenor Matthew Brook bass-baritone For the full liturgy of the reconstruction of J.S. Bach’s first Christmas in Leipzig, please see pages 12–13. Additional content is available for download from www.linnrecords.com/recording-bach-magnificat.aspx for free. 2 Giovanni Gabrieli Magnificat in E flat major, BWV 243a q Motet: Hodie Christus natus f Magnificat .................................... 2:55 2:54 est a8 ............................................ g Et exsultavit ................................ 2:24 h Vom Himmel hoch .................... 1:30 Johann Sebastian Bach j Quia respexit .............................. 2:35 w Organ Prelude: Gott, durch k Omnes generationes ................. 1:21 deine Güte, BWV 600 ............. 1:00 l Quia fecit ...................................... 1:43 ; Freut euch und jubiliert .......... 1:20 Cantata: Christen, ätzet diesen Tag, 2) Et misericordia .......................... 3:30 BWV 63 2! Fecit potentiam ......................... 1:56 e Chorus: Christen, ätzet 2@ Gloria in excelsis Deo! ............. 1:06 diesen Tag .................................... 5:21 2# Deposuit potentes .................... 2:01 r Recit: O selger Tag! .................. 2:57 2$ Esurientes implevit bonis ....... 3:18 t Aria: Gott, du hast es wohl 2% Virga Jesse ................................ 2:58 gefüget ......................................... 7:26 2^ Suscepit Israel ........................... 2:03 y Recit: So kehret sich 2& Sicut locutus est ........................ 1:24 nun heut ...................................... 0:49 2* Gloria ............................................. 2:16 u Aria: Ruft und fleht den Himmel an .................................. -

Choral, Organ, and Instrumental Repertoire 2005-2006

Choral, Organ, and Instrumental Repertoire 2005-2006 Cathedral of Saint Joseph the Workman La Crosse, Wisconsin Brian Luckner, DMA Director of Music and Organist Notes • The following document lists the music for choir alone, organ alone, and solo instrument or instrumental ensemble alone, which was sung or played at liturgies in the course of the 2005-06 choir season at the Cathedral of Saint Joseph the Workman in La Crosse, Wisconsin. • Unless choir or an instrument/ensemble is indicated before a title, the piece is for organ alone. • All organ repertoire listed was played by Brian Luckner. • All choral music listed was sung by the Cathedral Gallery Singers, with the exception of that sung for the Chrism Mass and the Ordination to the Priesthood. For these two liturgies, the Diocesan Chorale sang the choral repertoire. Both ensembles are under the direction of Brian Luckner. • For the weekday Masses, unless an occasion is addressed in some way by the organ music played, the day is simply listed as being a day of the week in a particular season. For example, although May 3 is the Feast of Saints Philip and James, Apostles, it is listed here as Wednesday in Easter Season. • Days omitted are days that Dr. Luckner did not play. Sept. 11 Twenty-fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time Passacaglia (BuxWV 161) Dietrich Buxtehude (1637-1707) Choir: Have Mercy on Me Thomas Tomkins (1573-1656) Choir: Cantate Domino Hans Leo Hassler (1564-1612) Canzona in A minor Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583-1643) Sept. 14 Exaltation of the Cross Vexilla Regis prodeunt (Op. -

Bach: the Complete Organ Works, Vol. 12

r Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier, BWV 706/1 [1.28] JOHANNJOHANN SEBASTIANSEBASTIAN BACH x Wenn wir in höchsten Nöten sein, BWV 641 [1.39] TheThe CompleteComplete Organ Organ Works, Works, Vol. 1112 c Wer nur denToccata, lieben Gott Adagio lässt walten, and Fugue BWV 642 in C,[1.30] BWV 564 vt Alle MenschenI. Toccata müssen sterben, BWV 643 [1.28] [5.36] DAVID GOODEGOODE by Ach wie nichtig,II. Adagio ach wie flüchtig, BWV 644 [0.50] [3.52] u III. Fugue [4.17] TrinityTrinity CollegeCollege Chapel,Chapel, CambridgeCambridge Total Timings [75.23] Total timings [69.24] Prelude and Fugue in C major, BWV 549 1 OrgelbüchleinI. Prelude [2.20] s 21 Nun komm,II. Fugue der Heiden Heiland, BWV 599 [1.14] Christus, der uns selig macht, BWV[3.46] 620 [2.15] the young Sebastian was a choral scholar d BACH, BEAUTY AND BELIEF 2 Gott durch deine Güte, BWV 600 [1.04] Da Jesus an dem Kreuze stund, BWV 621 [1.26] and likely had his first experiences in organ 33 f O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde groß, BWV 622 [4.56] THE ORGAN WORKS OF J.S. Herr Christ,Christ der lag ein’ge in Todesbanden, Gottes Sohn, BWV BWV 601 718[1.25] [5.01] building and maintenance.2 In 1700 he 4 g Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ, BWV 623 [1.02] BACH Lob sei dem allmächtigen Gott, BWV 602 [0.46] moved to Lüneburg, as a choral scholar 5 Puer natusFantasia in Bethlehem, and Imitatio BWV 603 in B minor, [1.42]BWV 563 h Hilf Gott, dass mir’s gelinge, BWV 624 [1.29] at St Michael’s School; this move brought 46 GelobetI. -

Andrew Elliot Henderson -- Complete List of Organ Repertoire Last Updated: August 24, 2013

Andrew Elliot Henderson -- Complete List of Organ Repertoire Last Updated: August 24, 2013 Composer Title Alain, Jehan (1911-1940) Choral Dorien Le Jardin Suspendu Litanies (1937) Postlude pour l’office de Complies Bach, C.P.E. (1714-1788) Präludium in D major, Wq. 70/7; Adagio (from Sonata in G minor, Wq. 70/6) Bach, Johann Michael (1648-1694) In Dulci Jubilo Bach, Johann Sebastian (1685-1750) From Clavierübung III : Dies sind die heiligen zehen Gebot (679); Wir glauben all an einen Gott (681); Christ, unser Herr, zum Jordan kam (684). From Leipzig Chorales : Komm Heiliger Geist, Herre Gott (651); An Wasserflüssen Babylon (653); Schmücke dich, O liebe Seele (654); O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig (656); Nun komm’ der Heiden Heiland (659, 660, 661); Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr’ (664); Komm, Gott, Schöpfer, Heiliger Geist (667); Wenn wir in höchsten Nöthen sein (668). From Orgelbüchlein : Nun komm’ der Heiden Heiland (599); Gottes sohn ist kommen (600); Herr Christ, der ein’ge Gottes-Sohn (601); Lob sei dem allmächtigen Gott (602); Puer natus in Bethlehem (603); Der Tag, der ist so freudenreich (605); In Dulci Jubilo (608); Lobt Gott, ihr Christen allzugleich (609); Das alte Jahr vergangen ist (614); In dir ist Freude (615); Mit Fried’ und Freud’ (616); Herr Gott, nun schleuss der Himmel auf (617); O Lamm Gottes unschuldig (618); Christe, du Lamm Gottes (619); Da Jesus an dem Kreuze stund (621); O Mensch, bewein’ dein’ Sünde groß (622); Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ (623); Christ lag in Todesbanden (625); Jesus Christus, unser Heiland (626); Erstanden ist der heil’ge Christ (628); Erschienen ist der herrlich Tag (629); Komm, Gott, Schöpfer (631); Herr Jesus Christ, dich zu uns wend’ (632); Liebster Jesu (633b); Vater unser im Himmelreich (636); Ich ruf’ zu dir (639) (& BWV Anh. -

Magnificat and Organ Julia Thomas Preludes): Carus-Verlag (Cantata) Dunedin Consort/David Lee (Motet and Congregational Chorales)

DUNEDIN CONSORT JOHN BUTT CHRISTMAS CANTATA 63 Reconstruction of Bach’s first Christmas Vespers in Leipzig in E flat major, BWV 243a and Cantata, BWV 63, within a reconstruction of J.S. Bach’s first Christmas in Leipzig: Vespers in the Nikolaikirche, 25 December 1723 Dunedin Consort John Butt Julia Doyle soprano Joanne Lunn soprano Clare Wilkinson mezzo-soprano Nicholas Mulroy tenor Matthew Brook bass-baritone Recorded at Cover image Greyfriars Kirk, Edinburgh, UK The Adoration of the Shepherds (1646) 27–31 July 2014 by Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, National Gallery, London, UK, courtesy of Produced and recorded by Bridgeman Images Philip Hobbs Design by Assistant engineering by Gareth Jones & gmtoucari.com Robert Cammidge Performing Editions Post-production by Bärenreiter-Verlag (Magnificat and organ Julia Thomas preludes): Carus-Verlag (cantata) Dunedin Consort/David Lee (motet and congregational chorales) 2 Booklet text by John Butt English .................................................................................................................. 6 Español ............................................................................................................... 12 Deutsch ............................................................................................................... 19 Text & Translations ....................................................................................... 27 Biographies (only in English) ................................................................... 37 3 Reconstruction of J.S. -

J.S. Bach Chorales

J.S. Bach Chorales a new critical and complete edition arranged by BWV catalogue number with text and historical contextual information included for each chorale with numerous indices includedCOPY in the appendix PERUSAL Edited by Luke Dahn www.bach-chorales.com www.bach-chorales.comLUXSITPRESS COPY PERUSAL www.bach-chorales.com i General Table of Contents Preface ii Individual Chorales iii Layout Overview / Abbreviations ix The Chorales BWVs 1-197a Chorales from the Cantatas 1 BWVs 226-248 Chorales from the Motets, Passions, and Christmas Oratorio 81 BWVs 250-1126 Individual Chorales 97 Indices A. Index of Chorale Melody Titles 179 B. Index of Chorale Tune Composers and Origins 181 C. Index of Melodies (by scale-degree number) 184 D. Index of Melodies (by Zahn number) 191 E. Index of Chorale Text Titles 193 F. Index of Chorale Text Authors and Origins 196 G. Index of Chorales by Liturgical Occasion 200 H. Index of Chorales by Date COPY 202 I. Cross Indices I1. BWV-to-Dietel / Dietel-to-BWV 206 I2. BWV-to-Riemenschneider 207 I3. Riemenschneider-to-BWV 208 I4. Dietel-to-Riemenschneider / Riemenschneider-to-Dietel 209 I5. Riemenschneider-to-BWV 210 J. Chorales not in Breitkopf-Riemenschneider 211 K. Breitkopf-Riemenschneider Chorales Appearing in Different Keys 213 L. Chorale duplicates in Breitkopf-Riemenschneider 214 M. Realizations of Schemelli Gesangbuch Chorales 215 N. Chorale Instrumentation and Texture Index 216 PERUSAL www.bach-chorales.com ii PREFACE This new edition of the Bach four-part chorales is intentionally created and organized to serve all those who engage with the Bach chorales, from music theorists and theory students interested in studying the Bach chorale style or in using the chorales in the classroom, to musicologists and Bach scholars interested in the most up-to-date research on the chorales, to choral directors and organists interested in performing the chorales, to amateur Bach-lovers alike.