The Proceedings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

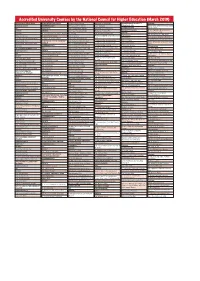

Accredited Programsa1

Accredited University Courses by the National Council for Higher Education (March 2019) AFRICA INSTITUTE OF MUSIC AFRICAN BIBLE UNIVERSITY B. Arts In Social Sciences Advanced Dip. Multimedia BISHOP BARHAM UNIVERSITY Graduate UNDERGRADUATE UNDERGRADUATE B. Business Admin. And Mgt Cert. Multimedia COLLEGE OF UCU Master Of Social Economics & Community OTI UNIVERSITY Dip. Business Admin. And Mgt Advanced Dip. Software Eng. UNDERGRADUATE Mgt (M.a.secm) B. Scie. Agricluture Economies And PRIVATE PRIVATE Dip. Project Planning And Mgt Higher Dip. Software Eng. UNIVERSITY COLLEGE Natural Resources Mgt Dip. Music B. Arts In Christian Community Leadership B. Theology Dip. Information Systems Mgt PRIVATE Dip. Human Resource Mgt (Dhrm) Advanced Dip. Music B. Arts In Biblical Studies Dip. Social Work Professional Dip. Electrical & Electronics Dip. Education B. Cooperative Mgt & Devt (Bcomd) Dip. Intercultural Studies Highlighted Postgrad. Dip. Business Admin. Dip. Project Planning And Mgt Cad Dip. Theology B. Human Resource Mangement (Bhrm) Advanced Dip. Music AFRICAN COLLEGE OF COMMERCE Dip. Information And Comm. Tech. Professional Dip. Architectural Cad B. Arts In Divinity Master Of Agriculture & Rural Innovations KABALE Professional Dip. Mechanical Cad Dip. Gender Studies Advanced Dip. Intercultural Studies Dip. Entrepreneurship And Mgt (Mari) Professional Dip. Civil Cad B. Arts With Education Dip. Music UNDERGRADUATE Dip. Theology And Community Devt Undergraduate Higher Dip. Hardware And Networking Dip. Mass Comm. AFRICA POPULATION INSTITUTE OTI Dip. Procurement And Logistics Mgt Dip. Public Admin. (Dpa) Advanced Dip. Software Eng. B. Education (Full-Time) UNDERGRADUATE PRIVATE B. Arts In Social Sciences B. Public Admin. (Bpa) Higher Dip. Software Eng. B. Education (Recess) OTI Dipoma In Renewable Energies Dip. -

Hinari Participating Academic Institutions

Hinari Participating Academic Institutions Filter Summary Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Bamyan Bamyan University Chakcharan Ghor province regional hospital Charikar Parwan University Cheghcharan Ghor Institute of Higher Education Faizabad, Afghanistan Faizabad Provincial Hospital Ferozkoh Ghor university Gardez Paktia University Ghazni Ghazni University Ghor province Hazarajat community health project Herat Rizeuldin Research Institute And Medical Hospital HERAT UNIVERSITY 19-Dec-2017 3:13 PM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 1 of 367 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Herat Herat Institute of Health Sciences Herat Regional Military Hospital Herat Regional Hospital Health Clinic of Herat University Ghalib University Jalalabad Nangarhar University Alfalah University Kabul Kabul asia hospital Ministry of Higher Education Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) Afghanistan Public Health Institute, Ministry of Public Health Ministry of Public Health, Presidency of medical Jurisprudence Afghanistan National AIDS Control Program (A-NACP) Afghan Medical College Kabul JUNIPER MEDICAL AND DENTAL COLLEGE Government Medical College Kabul University. Faculty of Veterinary Science National Medical Library of Afghanistan Institute of Health Sciences Aga Khan University Programs in Afghanistan (AKU-PA) Health Services Support Project HMIS Health Management Information system 19-Dec-2017 3:13 PM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 2 of 367 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Kabul National Tuberculosis Program, Darulaman Salamati Health Messenger al-yusuf research institute Health Protection and Research Organisation (HPRO) Social and Health Development Program (SHDP) Afghan Society Against Cancer (ASAC) Kabul Dental College, Kabul Rabia Balkhi Hospital Cure International Hospital Mental Health Institute Emergency NGO - Afghanistan Al haj Prof. Mussa Wardak's hospital Afghan-COMET (Centre Of Multi-professional Education And Training) Wazir Akbar Khan Hospital French Medical Institute for children, FMIC Afghanistan Mercy Hospital. -

Nkumba Business Journal

Nkumba Business Journal Volume 17, 2018 NKUMBA UNIVERSITY 2018 1 Editor Professor Wilson Muyinda Mande 27 Entebbe Highway Nkumba University P. O. Box 237 Entebbe, Uganda E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] ISSN 1564-068X Published by Nkumba University © 2018 Nkumba University. All rights reserved. No article in this issue may be reprinted, in whole or in part, without written permission from the publisher. Editorial / Advisory Committee Prof. Wilson M. Mande, Nkumba University Assoc. Prof. Michael Mawa, Uganda Martyrs University Dr. Robyn Spencer, Leman College, New York University Prof. E. Vogel, University of Delaware, USA Prof. Nakanyike Musisi, University of Toronto, Canada Dr Jamil Serwanga, Islamic University in Uganda Dr Fred Luzze, Uganda-Case Western Research Collaboration Dr Solomon Assimwe, Nkumba University Dr John Paul Kasujja, Nkumba University Prof. Faustino Orach-Meza, Nkumba University Peer Review Statement All the manuscripts published in Nkumba Business Journal have been subjected to careful screening by the Editor, subjected to blind review and revised before acceptance. Disclaimer Nkumba University and the editorial committee of Nkumba Business Journal make every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in the Journal. However, the University makes no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the suitability for any purpose of the content and disclaim all such representations and warranties whether express or implied to the maximum extent permitted by law. The views expressed in this publication are the views of the authors and are not necessarily the views of the Editor, Nkumba University or their partners. Correspondence Subscriptions, orders, change of address and other matters should be sent to the editor at the above address. -

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary material BMJ Global Health Supplementary Table 1 List of African Universities and description of training or research offerings in biological science, medicine and public health disciplines Search completed Dec 3rd, 2016 Sources: 4icu.org/africa and university websites University Name Country/State City Website School of School of School of Biological Biological Biological Biological Medicine Public Health Science, Science, Science, Science Undergraduate Masters Doctoral Level Level Universidade Católica Angola Luanda http://www.ucan.edu/ No No Yes No No No Agostinhode Angola Neto Angola Luanda http://www.agostinhone Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes UniversidadeUniversity Angola Luanda http://www.unia.ao/to.co.ao/ No No No No No No UniversidadeIndependente Técnica de de Angola Luanda http://www.utanga.co.ao No No No No No No UniversidadeAngola Metodista Angola Luanda http://www.uma.co.ao// Yes No Yes Yes No No Universidadede Angola Mandume Angola Huila https://www.umn.ed.ao Yes Yes No Yes No No UniversidadeYa Ndemufayo Jean Angola Viana http://www.unipiaget- No Yes No No No No UniversidadePiaget de Angola Óscar Angola Luanda http://www.uor.ed.ao/angola.org/ No No No No No No UniversidadeRibas Privada de Angola Luanda http://www.upra.ao/ No Yes No No No No UniversidadeAngola Kimpa Angola Uíge http://www.unikivi.com/ No Yes No No No No UniversidadeVita Katyavala Angola Benguela http://www.ukb.ed.ao/ No Yes No No No No UniversidadeBwila Gregório Angola Luanda http://www.ugs.ed.ao/ No No No No No No UniversidadeSemedo José Angola Huambo http://www.ujes-ao.org/ No Yes No No No No UniversitéEduardo dos d'Abomey- Santos Benin Atlantique http://www.uac.bj/ Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Calavi Université d'Agriculture Benin Plateau http://www.uakbenin.or No No No No No No de Kétou g/ Université Catholique Benin Littoral http://www.ucao-uut.tg/ No No No No No No de l'Afrique de l'Ouest Université de Parakou Benin Borgou site cannot be reached No Yes Yes No No No Moïsi J, et al. -

Proceedings of 14Th Annual IS Conference

Proceedings of 14th Annual IS Conference Theme “Information Ethics in Africa” Editors Dennis Ocholla and Janneke Mostert Proceedings of 14th Annual IS Conference 2013 Proceedings of 14th Annual IS Conference Published by the Department of Information Studies- [Online] http://www.lis.uzulu.ac.za University of Zululand Private Bag x1001 KwaDlangezwa 3886 South Africa Email: [email protected] : [email protected] All rights reserved © Authors 2013 ISBN 978-0-620-45757-6 Cover design: Ntobeko Mthembu Copy Editor: Prof. C.T. Moyo Conference Chair Prof.Janneke Mostert Programme Chair Prof. Dennis N. Ocholla Programme Committee Mr. Coetzee Bester - University of Pretoria Ms. Rachel Bothma - University of Pretoria Prof. Theo Bothma - University of Pretoria Prof. Johannes Britz- University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, USA Prof. Rafael Capurro - International Centre for Information Ethics, Germany Mr. Neil Evans – University of Zululand, South Africa Prof. Daisy Jacobs – University of Zululand Prof. Jerry Le Roux – University of Zululand Prof. Bosire Onyancha- University of South Africa Prof. Janneke Mostert – University of Zululand Prof. Stephen Mutula- University of KwaZulu Natal, South Africa Mr. Ntando Nkomo- University of Zululand Prof. Daniel Rotich – Moi University, Kenya Mr. Mzwandile Shongwe- University of Zululand ii Proceedings of 14th Annual IS Conference 2013 Proceedings of 14th Annual IS Conference Contents A consideration of Teaching Information Ethics on Second Year Level at the University of Pretoria: A case-study of Integrating Theoretical Information Ethics with Practical Application. Erin Hommes and Rachel Bothma…………………………………………………………...…………………….1 Does Open Access Prevent Plagiarism in Higher Education? Dennis N. Ocholla and Lyudmila Ocholla………………………….……………………………………...………10 Electronic Waste: the Dumping Site of the Information Age Laetitia Marais and Marlene A. -

Research4life Academic Institutions

Research4Life Academic Institutions Filter Summary Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Bamyan Bamyan University Charikar Parwan University Cheghcharan Ghor Institute of Higher Education Ferozkoh Ghor university Gardez Paktia University Ghazni Ghazni University HERAT HERAT UNIVERSITY Herat Institute of Health Sciences Ghalib University Jalalabad Nangarhar University Alfalah University Kabul Afghan Medical College Kabul 20-Apr-2018 9:40 AM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 1 of 174 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Kabul JUNIPER MEDICAL AND DENTAL COLLEGE Government Medical College Kabul University. Faculty of Veterinary Science Aga Khan University Programs in Afghanistan (AKU-PA) Kabul Dental College, Kabul Kabul University. Central Library American University of Afghanistan Agricultural University of Afghanistan Kabul Polytechnic University Kabul Education University Kabul Medical University, Public Health Faculty Cheragh Medical Institute Kateb University Prof. Ghazanfar Institute of Health Sciences Khatam al Nabieen University Kabul Medical University Kandahar Kandahar University Malalay Institute of Higher Education Kapisa Alberoni University khost,city Shaikh Zayed University, Khost 20-Apr-2018 9:40 AM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 2 of 174 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Lashkar Gah Helmand University Logar province Logar University Maidan Shar Community Midwifery School Makassar Hasanuddin University Mazar-e-Sharif Aria Institute of Higher Education, Faculty of Medicine Balkh Medical Faculty Pol-e-Khumri Baghlan University Samangan Samanagan University Sheberghan Jawzjan university Albania Elbasan University "Aleksander Xhuvani" (Elbasan), Faculty of Technical Medical Sciences Korca Fan S. Noli University, School of Nursing Tirana University of Tirana Agricultural University of Tirana 20-Apr-2018 9:40 AM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 3 of 174 Country City Institution Name Albania Tirana University of Tirana. -

Gulu University Office of the Academic Registrar Admissions List for 2016/2017 Academic Year

GULU UNIVERSITY OFFICE OF THE ACADEMIC REGISTRAR ADMISSIONS LIST FOR 2016/2017 ACADEMIC YEAR DIPLOMA ENTRY SCHEME GULU UNIVERSITY MAIN CAMPUS STUDENTS ADMITTED UNDER GOVERNEMENT SPONSORSHIP BACHELOR OF MEDICINE AND BACHELOR OF SURGERY (GUM) NO. NAME SEX DISTRICT DIPLOMA YEAR INSTITUTION DIPLOMA IN CLINICAL MED. AND GULU SCHOOL OF CLINICAL 1 AKUKU JAMES M ADJUMANI 2007 COM. HEALTH OFFICERS DIPLOMA IN CLINICAL MED. AND MEDICARE HEALTH 2 BIYINZIKA NORAH MARY F WAKISO 2015 COM. HEALTH PROFESSIONALS COLLEGE DIPLOMA IN CLINICAL MED. AND MBALE SCHOOL OF CLINICAL 3 DRAMADRI ALEX M YUMBE 2012 COM. HEALTH OFFICERS DIPLOMA IN CLINICAL MED. AND FORT PORTAL SCHOOL OF 4 OGWAL JOHN BAPTIST M ALEBTONG 2010 COM. HEALTH CLINICAL OFFICERS DIPLOMA IN CLINICAL MED. AND GULU SCHOOL OF CLINICAL 5 OJOK ISAAC ODONGO M APAC 2013 COM. HEALTH OFFICERS BACHELOR OF SCIENCE EDUCATION (PHYSICAL) (WEEKDAY) - SEG NO. NAME SEX DISTRICT DIPLOMA YEAR INSTITUTION DIPLOMA IN WATER AND UGANDA TECHNICAL 1 MUSINGUZI JOHNSON M KYENJOJO SANITATION ENGINEERING 2014 COLLEGE - KICHWAMBA (PHY/MAT) DIPLOMA IN EDUCATION 2 OGWANG ROBERT M OTUKE 2013 KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY SECONDARY (PHY/MAT) BACHELOR OF SCIENCE EDUCATION (ECONOMICS) (WEEKDAY) - GEE NO. NAME SEX DISTRICT DIPLOMA YEAR INSTITUTION DIPLOMA IN BUSINESS STUDIES 1 OCAATRE INNOCENT M MARACHA 2012 MUBS (ECO/GEO) BACHELOR OF SCIENCE EDUCATION (BIOLOGICAL) (WEEKDAY) - GBE NO. NAME SEX DISTRICT DIPLOMA YEAR INSTITUTION DIPLOMA IN EDUCATION 1 ODONGO FREDERICK M OYAM 2001 KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY SECONDARY (BIO/GEO) BACHELOR OF SCIENCE EDUCATION (SPORTS SCIENCE) (WEEKDAY) - GSS NO. NAME SEX DISTRICT DIPLOMA YEAR INSTITUTION 1 OTTO DICK ODONG M GULU DIPLOMA IN ANIMAL PRODUCTION 2015 BUSITEMA UNIVERSITY BACHELOR OF QUANTITATIVE ECONOMICS (WEEKDAY) (GQE) NO. -

North South Cooperation by Academics and Academic Institutions.Pdf

North south cooperation by academics and academic institutions: The case of Uganda A.B.K.Kasozi, PhD (California) Research Associate, Makerere Institute of Social Research Former Executive Director, National Council for Higher Education, Uganda. 1. Introduction As latecomers in the establishment of knowledge creation centres (universities, polytechnics and research centres), African higher education institutions need to collaborate with universities in regions and states that have had these institutions for centuries. But this cooperation must be well defined and all areas of cooperation known to each party. Past macro cooperation was often given in donor/aid recipient frameworks and often increased the dependency of southern partners to the north. Therefore, the levels, types and methods of co-operation must be thoroughly defined to avoid the mistakes of the past. The ideal mode of cooperation, which may not be achieved immediately, should be based on the following ten mark stones. First, both partners must do the designing of any joint research or teaching project cooperatively. The southern partner must make sure that the project will create knowledge that is useful to his/her constituency in the south. Africa needs, like the north did in its process of development, home focused and home-grown knowledge and thinkers who can use local conceptual models to resolve local problems. Secondly, both partners must have the capacity to, and should, contribute equal intellectual inputs in the designing of a project. People of unequal intellectual levels are unlikely to work well together. Thirdly, the partners must share the execution of the project. Each party should be assigned areas of work and the targets to be achieved at given time frames. -

Download Course Fees Structure

Attained ‘O’level or “A” level DETAILED ADMISSION REQUIREMENTS PER PROGRAMME AND FEES STRUCTURE HEQ Higher Education 1 year obtained at the same sitting but 505,000= 200 Tuition Fee Tuition Fee Qualification failed to get the required minimum per Sem. per Sem. [EA] Certificate qualification for entry into Code Programme Duration Admissions Requirements Non- EA Citizens Cert/Dip/Degree Citizens [Ugx] At least one principal pass and two [USD] Diploma in Business subsidiaries at UACE obtained at the Certificate in DBAM Administration and 2 years same sitting or its equivalent or 555,000= 200 Management credit certificate from recognized CBAM Business At least three passes at ‘O’level 505,000= 200 institution Administration and 2 years obtained at the same sitting or its At least one principal pass and two 655,000= 240 Mgt. equivalent Diploma in subsidiaries at UACE obtained at the Certificate in At least three passes at ‘O’level 605,000= 240 DICT Information and 2 years same sitting or its equivalent or a CICT Information and obtained at the same sitting or its Communication credit certificate from a recognized 2 years Communication equivalent Technology institution. Technology At least one principal pass and two Diploma in subsidiaries at UACE obtained at the Certificate in At least three passes at ‘O’level DJMC Journalism & Mass 2 years same sitting or its equivalent or a 655,000= 240 CPLM Procurement and 2 years obtained at the same sitting or its Comm. credit certificate from a recognized Logistics equivalent 505,000= 200 institution Management At least one principal pass and two Certificate in Social At least three passes at ‘O’level Diploma in Social subsidiaries at UACE obtained at the CSWA Work and Social 2 years obtained at the same sitting or its 505,000= 200 DSWA Work and Social 2 years same sitting or its equivalent or a 555,000= 220 Administration equivalent. -

RECOGNISED TERTIARY INSTITUTIONS PUBLIC UNIVERSITIES No Insititutions Name and Address 1 Makerere University P.O. Box 7062, Kamp

RECOGNISED TERTIARY INSTITUTIONS PUBLIC UNIVERSITIES No Insititutions Name and Address 1 Makerere University P.O. Box 7062, Kampala www.muk.ac.ug 2 Mbarara University of Science and Technology P.O. Box 1410, Mbarara www.must.ac.ug 3 Gulu University P.O. Box 166, Gulu www.gu.ac.ug/ 4 Kyambogo University P.O. Box 1, Kyambogo www.kyu.ac.ug 5 Busitema University P.O. Box 236, Tororo htp://busitema.ac.ug/ 6 Muni University P.O.Box 725, Arua Email: [email protected] www.muni.ac.ug 7 Kabale University P.O. Box 317, Kabale, Kikungiri 8 Lira University Plot 1162, Ayere Barapwo P.O.Box 1035, Lira Tel: 0471660714 8 Soroti University Plot 50 & 51 Arapai P.O.Box 211, Soroi Tel: 0454461605 www.su.ac.ug PUBLIC UNIVERSITY COLLEGES No Insituions Name and Address 1 Makerere University Business School P.O. Box 7062 Kampala, Uganda. Tel: +256-41- 32752/530231/5302232. Website: htp://mak.ac.ug. Fax: +256 -41 533640/ 541068. 2 Makerere University College of Health Sciences P.O. Box 7062, Kampala htp://chs.mak.ac.ug/ 3 Makerere University College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences P.O. Box 7062, Kampala htp://sas.mak.ac.ug/ 4 Makerere University College of Business and Management Science P.O. Box 7062, Kampala htp://bams.mak.ac.ug 4 Makerere University College of Compuing and Informaion Sciences P.O. Box 7062, Kampala htp://cis.mak.ac.ug 5 Makerere University College of Educaion and External Studies P.O. Box 7062, Kampala htp://cees.mak.ac.ug 6 Makerere University College of Engineering, Design, Art & Technology P.O. -

Uv Cf Bulletin V Olume 7 2018

UVCF BULLETIN VOL 7 UVCF BULLETIN VOLUME 7 2018 VOLUME BULLETIN UVCF PREVIOUS PUBLISHED UVCF BULLETINS VOLUME 7 2018 ISSN 2306-6288 00 Layout Design,Typesetting & Printing: Email:.................................................. Volume 7, 2018 ISSN 2306-6288 Edited by Wilson Muyinda Mande UVCF BULLETIN VOL 7 UVCF Bulletin is a publication of the Uganda Vice Chancellors’ Forum (UVCF) P O BOX 23683 Kampala Uganda Tel. +256 772 454541 / +256 772 361 351 Email: [email protected] No paper in this issue may be reprinted in whole or in part without the written permission of the UVCF. Copyright: © UVCF ISSN 2306 - 6288 Credits: The editor is greatly indebted to all the people who contributed to the compilation of this issue of the UVCF Bulletin. Those who reconstructed papers from some oral presentation, those who did the typesetting of the Bulletin and supervised the printing process. The UVCF underwrote all the expenses of producing this Bulletin. 1 UVCF BULLETIN VOL 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 1: Preliminaries Page Editorial (Wilson Muyinda Mande) ........................................... 00 The state, university and human resource planning in Uganda (Dr. Ruhakana Rugunda) ........................... 00 Part 2: Papers The National Plan for Universities to Develop Human Resources to Ensure Adequate Food Security in Uganda for the 21st Century (Professor Elly N. Sabiiti) .............. 00 The Role of Universities in the Development of Human Resources for Professions and the Business Sector in Uganda (Fred K. Muza) …………...…................ 00 The place of universities in national human resource planning for vision 2040’ (Joseph Muvawala) …........... 00 The significance of human resource planning at a macro level in Uganda (Wilson Muyinda Mande) ….…........................... -

![Jame Odongo: Researcher, Consultant and Facilitator]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9486/jame-odongo-researcher-consultant-and-facilitator-6429486.webp)

Jame Odongo: Researcher, Consultant and Facilitator]

CV [Jame Odongo: Researcher, Consultant and Facilitator] Name and James Odongo, ACAFS Uganda, P.o Box 72, Gulu, Email: [email protected], Address Tel: 256782891766; Skype: jamesodongo2; Linkedln profile: linkedin.com/in/james-odongo-10851b16 Proposed Consultant Position Nationality Ugandan Country Uganda, Kenya, South Sudan, DRC, Mauritius Experience Languages Ateso, Kiswahili, English, Luganda, Luo, etc Education, Certificate in Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability and Learning (MEAL), Humantarian Leadership Training & Academy, Jan-Feb. 2020 Qualifications Certified Professional Forensic Investigation from the International Institute of Certified Forensic Investigation Professionals 2018-2019 (completed, waiting for a certificate) CPA Student, Institute of Certified Public Accountants Uganda 2018-2021 Master of Science in Accounting and Finance Makerere University 2007-2010 Bachelor of Business Administration (Hons) Makerere University 2002- 2005 Summary of Policy brief analysis, Review of Accounting, Finance, and Auditing, policy development, Investigations, HR Experience development,. Research, Monitoring, Evaluation, publication, leading teams, logistics management, grant management, capacity building, financial management, communication and reporting, data collection, analysis and report writing, interviewing skills. Interrogation skills and Donor relationship management Employment Team Lead Researcher for Market survey/assessment on the current status of Motor cycles Spare parts, Record Petroleum products & premium tyres