North South Cooperation by Academics and Academic Institutions.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Informal Support for People with Alzheimer's Disease and Related D

Informal Support for People With Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias in Rural Uganda: A Qualitative Study Pia Ngoma Nankinga ( [email protected] ) Mbarara University of Science and Technology Samuel Maling Maling Mbarara University of Science and Technology Zeina Chemali Havard Medical School Edith K Wakida Mbarara University of Science and Technology Celestino Obua Mbarara University of Science and Technology Elialilia S Okello Makerere University Research Keywords: Informal support, dementia and rural communities Posted Date: December 17th, 2019 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.2.19063/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/16 Abstract Background: The generation of people getting older has become a public health concern worldwide. People aged 65 and above are the most at risk for Alzheimer’s disease which is associated with physical and behavioral changes. This nurtures informal support needs for people living with dementia where their families together with other community members are the core providers of day to day care for them in the rural setting. Despite global concern around this issue, information is still lacking on informal support delivered to these people with dementia. Objective: Our study aimed at establishing the nature of informal support provided for people with dementia (PWDs) and its perceived usefulness in rural communities in South Western Uganda. Methods: This was a qualitative study that adopted a descriptive design and conducted among 22 caregivers and 8 opinion leaders in rural communities of Kabale, Mbarara and Ibanda districts in South Western Uganda. The study included dementia caregivers who had been in that role for a period of at least six months and opinion leaders in the community. -

University Lecturers and Students Could Help in Community Education About SARS-Cov-2 Infection in Uganda

HIS0010.1177/1178632920944167Health Services InsightsEchoru et al 944167research-article2020 Health Services Insights University Lecturers and Students Could Help in Volume 13: 1–7 © The Author(s) 2020 Community Education About SARS-CoV-2 Infection Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions in Uganda DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1178632920944167 10.1177/1178632920944167 Isaac Echoru1 , Keneth Iceland Kasozi2 , Ibe Michael Usman3 , Irene Mukenya Mutuku1, Robinson Ssebuufu4 , Patricia Decanar Ajambo4, Fred Ssempijja3, Regan Mujinya3 , Kevin Matama5, Grace Henry Musoke6 , Emmanuel Tiyo Ayikobua7 , Herbert Izo Ninsiima1, Samuel Sunday Dare1,2, Ejike Daniel Eze1,2, Edmund Eriya Bukenya1, Grace Keyune Nambatya8, Ewan MacLeod2 and Susan Christina Welburn2,9 1School of Medicine, Kabale University, Kabale, Uganda. 2Infection Medicine, Deanery of Biomedical Sciences, and College of Medicine & Veterinary Medicine, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. 3Faculty of Biomedical Sciences, Kampala International University Western, Bushenyi, Uganda. 4Faculty of Clinical Medicine and Dentistry, Kampala International University Teaching Hospital, Bushenyi, Uganda. 5School of Pharmacy, Kampala International University Western Campus, Bushenyi, Uganda. 6Faculty of Science and Technology, Cavendish University, Kampala, Uganda. 7School of Health Sciences, Soroti University, Soroti, Uganda. 8Directorate of Research, Natural Chemotherapeutics Research Institute, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda. 9Zhejiang University-University of Edinburgh -

Higher Education Solutions Network (HESN) 2.0 Programs Bi-Annual Performance Report Narrative

Higher Education Solutions Network (HESN) 2.0 Programs Bi-Annual Performance Report Narrative 1. BACKGROUND LASER PULSE is a five-year USAID-funded consortium, led by Purdue University and also comprising Catholic Relief Services, Indiana University, Makerere University, and the University of Notre Dame. LASER PULSE supports the research-to-translation value chain through a global network of 1,000+ researchers, government agencies, non-governmental organizations, and the private sector for research-driven, practical solutions to critical development challenges in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). LASER supports the discovery and uptake of research-sourced, evidence-based solutions to development challenges spanning all USAID technical sectors and global geographic regions. The LASER PULSE strategy ensures that applied research is co-designed with development practitioners, and results in solutions that are useful and usable. LASER does this by involving development practitioners upfront - from topic selection, research question definition, conducting and testing research, and developing translation products for immediate use. We support this process with capacity building and technical assistance to enable the researcher/user partnerships to function effectively. 2. MAJOR MILESTONES / ACHIEVEMENTS 1. Researcher Capacity: Makerere University had an opportunity to engage with USAID Uganda’s Regional Development Initiative. The team accompanied the Uganda Regional Development Initiative team on several visits, to provide feedback on working with local universities in order to enhance their role in the path to self-reliance. This is a model that can be replicated in other countries and regions. The collaboration (Makerere and RDI) has resulted in a new buy-in opportunity for Makerere to work with regional universities in strengthening resilience for indigenous Ugandan groups). -

Dr-Eton-Marus-CV.Pdf

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME Eton Marus (PhD) DATE OF BIRTH Septembers 28th 1978 ADDRESS Kabale University, Uganda Box 317 Kabale 256772880149/256701304416 [email protected]/[email protected] PROFESSIONAL Finance/Accounts, Business, Marketing and Monitoring and Evaluation AREAS ACADEMIC YEARS INSTITUTION QUALIFICATIONS QUALIFICATIONS 2015-2018 Nkumba University PhD Business Administration (Finance) 2016-2017 Uganda Management Post Graduate Diploma In Institute-Kampala Monitoring and Evaluation 2010-2012 Cavendish University Masters in Business Administration 2009-2010 Gulu University Post Graduate Diploma in Financial Management 2002-2006 Makerere University Bachelor of Commerce 1998-2001 Makerere University Higher Diploma In Business School Marketing OTHER Grant and Proposal Writing and Management. (ACRA) Mbarara TRAININGS University of Science and Technology July 2019 Programme Skills Development (Assessing Academic and Professional Programmes, Uganda National Council of Higher Education, Kampala 2019. Researcher Connect Professional Development for Researchers (Proposal writings skills, Resource mobilization, Academic Collaborations, Networking, Grants Management and Persuasive Proposal writing. British Council Kampala 2019. Post Graduate Certificate in Monitoring and Evaluation, Makerere University 2014. Post Graduate Certificate in Administrative Law Makerere University 2013 Post Graduate Certificate in Procurement and Contract Management Uganda Management Institute-Kampala 2013 Post Graduate Certificate in Training of Trainers, -

Govt Takes Over Running of Busoga University

12 NEW VISION, Tuesday, February 6, 2018 REGIONAL NEWS Govt takes over running of Busoga University Amuru leaders clash KAMULI Authorities in Amuru have By Tom Gwebayanga National Forest Authority (NFA) over a planned re-opening of the The Government has announced boundaries of Olwal Central Forest its decision to take over the Reserve. Olwal Forest Reserve is management of the stressed private located in Olwal village, Giragira Busoga University in a bid to end parish, Lamogi sub-county in Amuru the woes that have rocked the district. It covers 1,384 hectares institution for over six years, the of land. The leaders, who included Speaker of Parliament, Rebecca Kilak South MP Gilbert Olanya Kadaga, has said. and Amuru LC5 chairman Michael Kadaga said President Yoweri Lakony, demanded that NFA Museveni last week okayed the stop planting mark stones along takeover of Busoga University to the boundaries of Olwal Forest relieve the public of last year’s tension as a result of its closure to plant the mark stones last week by the National Council for Higher because the leaders and residents Education (NCHE). protested the re-opening of the “It is over; the people of Busoga boundaries of the forest reserve, and beyond have every reason to claiming that NFA wants to grab smile,” Kadaga said. She said amidst the troubles of the bullets in the air to stop youth from university, a blessing has come after reloading the mark stones onto the President Museveni gave a directive NFA vehicle that had brought them. that the government takes over full control of the university, which is on the brink of collapse. -

Report Micro-Research Workshop Makerere University

Micro-Research Report Micro-Research Workshop Makerere University “Nurturing an Academic Career from Research Ideas to Finished Papers-using Micro-Research” Workshop for Community Based Researchers Held at Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda From August 2 to 13, 2010 Lecturers Robert Bortolussi, MD FRCPC, Professor Pediatrics, Noni MacDonald, MD, FRCPC, FCAHS, Professor of Pediatrics, IWK Health Centre and Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada and Eric Wobudeya, Department of Pediatrics and Paul Kutyabami, Department of Pharmacy, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda Ugandan Mentor Kasangaki Arabati, Faculty of Dentistry, Makerere University Funding Sponsors Micro-Research, IWK Health Centre And Canadian Child Health Clinician Scientist Program (CCHCSP) Report Makerere Workshop 2010 Page 1 Micro-Research Introduction and Background The absolute need for capacity building in research was recognized several years ago by African nations. Lack of grant funds for small research projects is a major obstacle to research development in developing countries. Small projects are the fuel, upon which research skills are honed and a track record is established, a critical factor in any research grant proposal. In March 2009, Drs. Noni MacDonald and Robert Bortolussi were awarded funds from CCHCSP for a pilot Micro-Research infrastructure project. Micro-Research, a concept modeled on Micro–Finance, was conceived by Jerome Kabakyenga, Dean of Medicine of Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST), Noni MacDonald and Bob Bortolussi in 2008 (Appendix 1). The CCHCSP pilot project would use educational tools, mentors, seed grant support and peer-to-peer interaction with CCHCSP and Ugandan researchers. The program of the workshop at Makerere University was modeled after an earlier workshop but modified to address issues such as grant reviewing, knowledge translation and community engagement. -

View/Download

Research Article Food Science & Nutrition Research Risk Factors to Persistent Dysentery among Children under the Age of Five in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa; the Case of Kumi, Eastern Uganda Peter Kirabira1*, David Omondi Okeyo2, and John C. Ssempebwa3 1MD, MPH; Clarke International University, Kampala, Uganda. *Correspondence: 2PhD; School of Public Health, Department of Nutrition and Peter Kirabira, Clarke International University, P.O Box 7782, Health, Maseno University, Maseno Township, Kenya. Kampala, Uganda, Tel: +256 772 627 554; E-mail: drpkirabs@ gmail.com; [email protected]. 3MD, MPH, PhD; Disease Control and Environmental Health Department, School of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Received: 02 July 2018; Accepted: 13 August 2018 Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. Citation: Peter Kirabira, David Omondi Okeyo, John C Ssempebwa. Risk Factors to Persistent Dysentery among Children under the Age of Five in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa; the Case of Kumi, Eastern Uganda. Food Sci Nutr Res. 2018; 1(1): 1-6. ABSTRACT Introduction: Dysentery, otherwise called bloody diarrhoea, is a problem of Public Health importance globally, contributing 54% of the cases of childhood diarrhoeal diseases in Kumi district, Uganda. We set out to assess the risk factors associated with the persistently high prevalence of childhood dysentery in Kumi district. Methods: We conducted an analytical matched case-control study, with the under five child as the study unit. We collected quantitative data from the mothers or caretakers of the under five children using semi-structured questionnaires and checklists and qualitative data using Key informer interview guides. Quantitative data was analysed using SPSS while qualitative data was analysed manually. -

Of Independent Public Universities in Mombasa, Kenya Kevin Brennan

A History of the Absence (and Emergent Presence) of Independent Public Universities in Mombasa, Kenya Kevin Brennan A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Education. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: George Noblit Julius Nyang‟oro James Trier Richard Rodman Gerald Unks © 2008 Kevin Brennan ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract Kevin Brennan A History of the Absence (and Emergent Presence) of Independent Public Universities in Mombasa, Kenya (Under the direction of George Noblit and Julius Nyang‟oro) While there is a great deal of literature available about schooling in Kenya and a good deal of writing about the establishment of Kenya‟s public university system there is a significant gap in the literature when it comes to describing and analyzing why certain areas of the country had long been removed from any on-site development of independent university opportunities. This study is an attempt to offer a history of an educational institution – an independent public university at the coast in Kenya – that does not yet exist. This longstanding absence took several significant steps toward transforming to a presence in 2007, when several university colleges were created at the coast. This transformation from absence to presence is a central theme in this work. The research for this project, broadly defined, took place over a seventeen year period and is rooted in both the author‟s professional experience as an educator working in Kenya in the early 1990s as well as his academic interests in comparative and international higher education. -

Prof. JWF Muwanga-Zake. Phd CV

Covering Letter and Curriculum Vitae for Associate Professor Johnnie Wycliffe Frank Muwanga-Zake Learning Technologist, Educator and Scientist with experience in Higher Education, Research and NGO institutions. Qualifications: B.Sc. (Hons) (Makerere); B.Ed., M.Sc., M.Ed. (Rhodes); PhD (Digital Media in Education, Natal); P.G.C.E. (NUL); P.G.D.E (ICT in Ed.) (Rhodes). To complete at the University of New England, Australia towards the Graduate Certificate in Higher Education. Current Position: Professor and Vice-Chancellor, Uganda Technology and Management University, Kampala. Contact: Emails: [email protected]; [email protected] . Copy to [email protected]. Mobile phone: +256788485749. A. Main Skills and Work Experiences A1. Leadership, administration and management experience (Close to 40 years) 1. Vice-Chancellor, , Uganda Technology and Management – October 2020 - Current. 2. Deputy Vice Chancellor, Uganda Technology and Management – January 2020 – October 2020. 3. Dean, School of Computing and Engineering, Uganda Technology and Management University, Kampala. 4. Associate Chief Editor, International Journal of Technology & Management, Uganda - Current. 5. Initiator and Project Advisor, Electronic Distance Learning (eDL), Cavendish University, Kampala. 6. Team Member of the World Bank project of African Centre of Excellence – Uganda Martyrs University- Current. 7. Dean, Faculty of Science and Technology, Cavendish University, Kampala. 8. Head of the IT Department and Senior Lecturer, School of Computing and Information Technology, Kampala International University. 9. Head, ICT Department, Uganda Martyrs University, Uganda. 10. Head, Learning Technology Forum, University of Greenwich, London. 11. Chairperson, Staff and Curriculum Development, University of Greenwich. 12. Head Coach, Armidale Football Club, Armidale, New South Wales, Australia. -

Effectiveness of Distributing HIV Self-Test Kits Through MSM Peer Networks in Uganda

Effectiveness of distributing HIV self-test kits through MSM peer networks in Uganda CROI 2019 Stephen Okoboi1, 2 Oucul Lazarus3, Barbara Castelnuovo1, Collins Agaba3, Mastula Nanfuka3, Andrew Kambugu1 Rachel King4,5 POSTER P-S3 0934 1. Infectious Diseases institute, 2.Clarke International University; 3.The AIDS Support Organization (TASO) ; 4.University of California, San Francisco; Global Health; 5.School of Public Health, Makerere University. Background Results Conclusions/Recommendation • Men who have sex with men (MSM) continue to be •MSM peers distributed a total of 150 HIVST kits to • Our pilot findings suggest that distributing disproportionately impacted globally by the HIV epidemic and MSM participants. HIVST through MSM peer-networks is are also highly stigmatized in Uganda. feasible, effective and a promising •A total of 10 participants were diagnosed with HIV strategy to increase uptake of HIV testing • Peer-driven HIV testing strategies can be effective in infection during the 3 months of kits distribution. and reduce undiagnosed infections identifying undiagnosed infections among high risk among MSM in Uganda populations •This was higher than 4/147 (2.7%) observed in the TASO program Jan-March 2018 (P=0.02). • Based on the pilot results, additional • We examined peer HIV oral fluid self-test kits (HIVST) studies to determine the large-scale network distribution effectiveness in identifying undiagnosed •All diagnosed HIV participants disclosed their test effectiveness of this strategy to overcome HIV infection among MSM in The AIDS Support Organization results to their peers, were confirmed HIV positive the barriers and increase HIV testing (TASO). at a health facility, and initiated on ART. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Professor Joy Constance Kwesiga (March 2020)

CURRICULUM VITAE Professor Joy Constance Kwesiga (March 2020) A. PERSONAL INFORMATION: NAME: Joy Constance Kwesiga DATE OF BIRTH: 03rd May 1943 SEX: Female NATIONALITY: Ugandan CONTACT: Kabale University P. O. Box 317 Kabale, Uganda. Tel: +256-772485267 / +256-751812325 E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] or [email protected] B. BRIEF BIO FOR JOY KWESIGA Professor Joy Constance Kwesiga, Ph.D (London), is an experienced academician, University Administrator and Social Development Analyst and a renowned gender and Women advocate and mentor. She has had an enviable privilege of combining academic work with women’s rights activist work. She has been a Professor of Gender Studies and the Vice Chancellor of Kabale University since November 2005 to date. She oversaw the transformation of Kabale University from a Private Community University to a Public University (since 2015). Even when Kabale University was a private University, she effectively steered it to attain an Operating Licence in 2005, and a University Charter in 2014. Previously, Professor Kwesiga served at various levels as a University Administrator at Makerere University, rising from the ranks to the level of Deputy Academic Registrar. She then switched to the academic arena, serving as the Head of the Department of Women and Gender Studies, and later became the Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at Makerere University. Professor Kwesiga was the founding Head of the Gender Mainstreaming Division of the Academic Registrar’s Department at Makerere University. The goal of the Gender Mainstreaming Programme is to make Makerere University an all-inclusive institution. Professor Kwesiga was able to lay its foundation. -

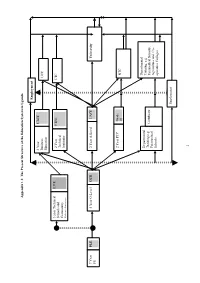

Appendix 1.1: the Present Structure of the Education System in Uganda

Appendix 1.1: The Present Structure of the Education System in Uganda Employment 3 Year UBEE Business UCC Education 3 year Technical UJTE 2 Year UTEE UTC Schools and Technical Community Institutes Polytechniques 7 Year PLE 4 Year O-Level UCE 2 Year A-Level UACE University PS 2 Year PTC Grade III NTC Departmental Departmental Training, e.g Training e.g. Certificate Paramedical Schools, Paramedical Agriculture and Co- Schools operative Colleges Employment I Appendix 1.2a: List of some of the Institutions of Higher Learning in Uganda (Universities (Public and Private) and Public other Tertiary Institutions as per May, 2005) b) Uganda Technical College (UTC)2 1. Universities • UTC Kichwamba • UTC Elgon a) Public • UTC Lira • Makerere University • UTC Masaka • Mbarara University of Science and • UTC Bushenyi Technology • Kyambogo University c) National Teachers’ Colleges (NTC) • Gulu University • NTC Unyama • NTC Kabale b) Public Degree Awarding Other Tertiary • NTC Nagongera Institution • NTC Muni • Uganda Management Institute1 • NTC Kaliro • NTC Mubende c) Private: Chartered Universities • Islamic University in Uganda d) Departmental Training Institutions • Uganda Christian University, Mukono • Uganda Martyrs University (Nkozi) i) Paramedical Schools • Arua Enrolled Nurses and Midwifery d) Private: Licensed to Operate • Butabika Psychiatric Clinical Officers • Bugema University • Butabika School of Nursing • Nkumba University • Fort Portal Clinical Officers School • Kampala International University • Gulu Clinical Officers School • Kampala University • Jinja Nurses and Midwifery • Ndejje University • Kabale Enrolled Nurses and Midwifery • Busoga University • Lira Enrolled Nurses and Midwifery • Kumi University • Masaka School of Comprehensive • Aga Khan University Nursing • Kabale University • Mbale Clinical Officers School • Mountains of the Moon University • Mbale School of Hygiene • Uganda Pentecostal University • Medical Laboratory School, Mulago • African Bible College • Medical Laboratory School, Jinja • Mulago Health Tutors College 2.