Proceedings of 14Th Annual IS Conference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effectiveness of Internship in Fostering Learning: the Case of African Rural University

Psychology Research, January 2016, Vol. 6, No. 1, 32-41 doi:10.17265/2159-5542/2016.01.004 D DAVID PUBLISHING Effectiveness of Internship in Fostering Learning: The Case of African Rural University Florence Ndibuuza African Rural University, Kagadi-Kibaale, Uganda Internship is deemed to be a prerequisite for a 21st Century graduate to survive in the world of work. It’s on the basis of this that this study sought to establish the effectiveness of internship in respect to learning in the field among undergraduates of African Rural University. The quantitative survey involved 23 students and 53 community members who filled a questionnaire and an interview guide respectively. Data analysis involved the use of percentages, means and multiple regression. The results of the study revealed that the three independent variables: cognitive, behavioral, and environmental learning experience (CLE, BLE and ELE) were not correlates of internship. It’s upon this background that it was recommended that the key players of the university ought to lay undue emphasis on enhancing CLE, BLE, and ELE, rather effort should be put on other elements to learning. Keywords: internship, learning, cognitive, behavioral and environmental experience Introduction Internship has been associated with several benefits to all key concerned stakeholders including the intern, academic institution and the employer. Accordingly studies (e.g., Steffen, 2010; Bukaliya, 2012; Papadimitriou, 2014) highlighted that internship provides authentic work experience to students. The institution is said to benefit through the increased cooperation and rapport with the internship organization, Bukaliya (2012) yet (Neugebauer, 2009; Steffen, 2010) mentioned that many employers use internship as the main tool for recruiting new talent. -

The Funding Network

16 Lincoln’s Inn Fields London WC2A 3ED tel: 0845 313 8449 email: [email protected] website: www.thefundingnetwork.org.uk Report back to The Funding Network 1. Name of your organisation and date funded by TFN: Sawa World (www.sawaworld.org), fall, 2012 2. What does your organisation do? i.e. What are its aims and objectives? Have these changed since receiving TFN funding? Sawa World is attempting to do something that has never been done before to tackle global poverty. It aims to create a world where 1 billion people in the world’s 50 poorest countries will lift themselves out of extreme poverty by having access to locally created and practical solutions within their communities; these solutions will thrive free of international charity. We believe that solutions come from within the communities that face dire poverty. Check out this great video where Sawa Youth Reporters from Uganda explain what we do: https://vimeo.com/63740942 3. When was your organisation first established? July 4, 2007 4. Since receiving funding from TFN how has your organisation changed? Has your annual turnover changed? Has the number of beneficiaries reached changed? Can you quantify any other changes? Eg number of employees, number of projects, geographical scope. Annual budget: grew by 10% Impact numbers: o Sawa Youth Reporters Trained– from 11 to 21. Four were full time employed o Solution Videos Produced – from 90 to 130 videos o People reach directly in extreme poverty – from 4,000 to 10,000 people o People reach indirectly (media) in extreme poverty – from 4.8 million to 6 million o Areas of expansion: Expanded the program to Western Uganda to the African Rural University o New partners: Sheraton Hotel Kampala (hosting the first Sawa World Day in 2014) and Private Education Development Network Uganda (working to expand program in 100 schools) 1 of 6 Registered Charity No. -

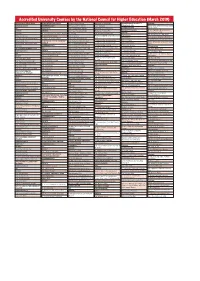

Accredited Programsa1

Accredited University Courses by the National Council for Higher Education (March 2019) AFRICA INSTITUTE OF MUSIC AFRICAN BIBLE UNIVERSITY B. Arts In Social Sciences Advanced Dip. Multimedia BISHOP BARHAM UNIVERSITY Graduate UNDERGRADUATE UNDERGRADUATE B. Business Admin. And Mgt Cert. Multimedia COLLEGE OF UCU Master Of Social Economics & Community OTI UNIVERSITY Dip. Business Admin. And Mgt Advanced Dip. Software Eng. UNDERGRADUATE Mgt (M.a.secm) B. Scie. Agricluture Economies And PRIVATE PRIVATE Dip. Project Planning And Mgt Higher Dip. Software Eng. UNIVERSITY COLLEGE Natural Resources Mgt Dip. Music B. Arts In Christian Community Leadership B. Theology Dip. Information Systems Mgt PRIVATE Dip. Human Resource Mgt (Dhrm) Advanced Dip. Music B. Arts In Biblical Studies Dip. Social Work Professional Dip. Electrical & Electronics Dip. Education B. Cooperative Mgt & Devt (Bcomd) Dip. Intercultural Studies Highlighted Postgrad. Dip. Business Admin. Dip. Project Planning And Mgt Cad Dip. Theology B. Human Resource Mangement (Bhrm) Advanced Dip. Music AFRICAN COLLEGE OF COMMERCE Dip. Information And Comm. Tech. Professional Dip. Architectural Cad B. Arts In Divinity Master Of Agriculture & Rural Innovations KABALE Professional Dip. Mechanical Cad Dip. Gender Studies Advanced Dip. Intercultural Studies Dip. Entrepreneurship And Mgt (Mari) Professional Dip. Civil Cad B. Arts With Education Dip. Music UNDERGRADUATE Dip. Theology And Community Devt Undergraduate Higher Dip. Hardware And Networking Dip. Mass Comm. AFRICA POPULATION INSTITUTE OTI Dip. Procurement And Logistics Mgt Dip. Public Admin. (Dpa) Advanced Dip. Software Eng. B. Education (Full-Time) UNDERGRADUATE PRIVATE B. Arts In Social Sciences B. Public Admin. (Bpa) Higher Dip. Software Eng. B. Education (Recess) OTI Dipoma In Renewable Energies Dip. -

Hinari Participating Academic Institutions

Hinari Participating Academic Institutions Filter Summary Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Bamyan Bamyan University Chakcharan Ghor province regional hospital Charikar Parwan University Cheghcharan Ghor Institute of Higher Education Faizabad, Afghanistan Faizabad Provincial Hospital Ferozkoh Ghor university Gardez Paktia University Ghazni Ghazni University Ghor province Hazarajat community health project Herat Rizeuldin Research Institute And Medical Hospital HERAT UNIVERSITY 19-Dec-2017 3:13 PM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 1 of 367 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Herat Herat Institute of Health Sciences Herat Regional Military Hospital Herat Regional Hospital Health Clinic of Herat University Ghalib University Jalalabad Nangarhar University Alfalah University Kabul Kabul asia hospital Ministry of Higher Education Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) Afghanistan Public Health Institute, Ministry of Public Health Ministry of Public Health, Presidency of medical Jurisprudence Afghanistan National AIDS Control Program (A-NACP) Afghan Medical College Kabul JUNIPER MEDICAL AND DENTAL COLLEGE Government Medical College Kabul University. Faculty of Veterinary Science National Medical Library of Afghanistan Institute of Health Sciences Aga Khan University Programs in Afghanistan (AKU-PA) Health Services Support Project HMIS Health Management Information system 19-Dec-2017 3:13 PM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 2 of 367 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Kabul National Tuberculosis Program, Darulaman Salamati Health Messenger al-yusuf research institute Health Protection and Research Organisation (HPRO) Social and Health Development Program (SHDP) Afghan Society Against Cancer (ASAC) Kabul Dental College, Kabul Rabia Balkhi Hospital Cure International Hospital Mental Health Institute Emergency NGO - Afghanistan Al haj Prof. Mussa Wardak's hospital Afghan-COMET (Centre Of Multi-professional Education And Training) Wazir Akbar Khan Hospital French Medical Institute for children, FMIC Afghanistan Mercy Hospital. -

Nkumba Business Journal

Nkumba Business Journal Volume 17, 2018 NKUMBA UNIVERSITY 2018 1 Editor Professor Wilson Muyinda Mande 27 Entebbe Highway Nkumba University P. O. Box 237 Entebbe, Uganda E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] ISSN 1564-068X Published by Nkumba University © 2018 Nkumba University. All rights reserved. No article in this issue may be reprinted, in whole or in part, without written permission from the publisher. Editorial / Advisory Committee Prof. Wilson M. Mande, Nkumba University Assoc. Prof. Michael Mawa, Uganda Martyrs University Dr. Robyn Spencer, Leman College, New York University Prof. E. Vogel, University of Delaware, USA Prof. Nakanyike Musisi, University of Toronto, Canada Dr Jamil Serwanga, Islamic University in Uganda Dr Fred Luzze, Uganda-Case Western Research Collaboration Dr Solomon Assimwe, Nkumba University Dr John Paul Kasujja, Nkumba University Prof. Faustino Orach-Meza, Nkumba University Peer Review Statement All the manuscripts published in Nkumba Business Journal have been subjected to careful screening by the Editor, subjected to blind review and revised before acceptance. Disclaimer Nkumba University and the editorial committee of Nkumba Business Journal make every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in the Journal. However, the University makes no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the suitability for any purpose of the content and disclaim all such representations and warranties whether express or implied to the maximum extent permitted by law. The views expressed in this publication are the views of the authors and are not necessarily the views of the Editor, Nkumba University or their partners. Correspondence Subscriptions, orders, change of address and other matters should be sent to the editor at the above address. -

The Evolution of African Rural University Co-Designed by Its Faculty, Students, and End-Customers (People the Grads Will Serve)

Patricia Seybold Group / Case Study The Evolution of African Rural University Co-Designed by Its Faculty, Students, and End-Customers (People the Grads Will Serve) By Patricia B. Seybold, CEO & Sr. Consultant, Patricia Seybold Group April 11, 2013 NETTING IT OUT This is the story of the creation of a unique institution—one that is likely to impact the lives of millions of people in Africa. It’s a story about having and realizing a vision—a BIG vision. The vision isn’t the creation of a successful university. The vision is about the work that the graduates of that university will be empowered to do. The vision is about the seeds of creativity and innovation that will be planted in the people these graduates touch. The African Rural University (ARU) is unique in a number of respects: 1. It offers transformative education—As a departure from the classic university education that emphasizes theory, ARU emphasizes the practicality of learning, hence there are many course hours devoted to contact with communities. 2. It is part of a continuum of educational institutions, from primary through secondary (URDT Schools) to university—all with similar learning threads in: the Principles of the Creative Process, community learning, entrepreneurship, creating social capital, and sustainable development in order to produce visionary leaders. 3. The curriculum is developed and evolves from the experiences and aspirations of the communities in which ARU is embedded. 4. ARU draws inspiration from its Traditional Wisdom Specialists, the old men and women who are repositories of traditional knowledge, and who serve as auxiliary "professors." 5. -

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary material BMJ Global Health Supplementary Table 1 List of African Universities and description of training or research offerings in biological science, medicine and public health disciplines Search completed Dec 3rd, 2016 Sources: 4icu.org/africa and university websites University Name Country/State City Website School of School of School of Biological Biological Biological Biological Medicine Public Health Science, Science, Science, Science Undergraduate Masters Doctoral Level Level Universidade Católica Angola Luanda http://www.ucan.edu/ No No Yes No No No Agostinhode Angola Neto Angola Luanda http://www.agostinhone Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes UniversidadeUniversity Angola Luanda http://www.unia.ao/to.co.ao/ No No No No No No UniversidadeIndependente Técnica de de Angola Luanda http://www.utanga.co.ao No No No No No No UniversidadeAngola Metodista Angola Luanda http://www.uma.co.ao// Yes No Yes Yes No No Universidadede Angola Mandume Angola Huila https://www.umn.ed.ao Yes Yes No Yes No No UniversidadeYa Ndemufayo Jean Angola Viana http://www.unipiaget- No Yes No No No No UniversidadePiaget de Angola Óscar Angola Luanda http://www.uor.ed.ao/angola.org/ No No No No No No UniversidadeRibas Privada de Angola Luanda http://www.upra.ao/ No Yes No No No No UniversidadeAngola Kimpa Angola Uíge http://www.unikivi.com/ No Yes No No No No UniversidadeVita Katyavala Angola Benguela http://www.ukb.ed.ao/ No Yes No No No No UniversidadeBwila Gregório Angola Luanda http://www.ugs.ed.ao/ No No No No No No UniversidadeSemedo José Angola Huambo http://www.ujes-ao.org/ No Yes No No No No UniversitéEduardo dos d'Abomey- Santos Benin Atlantique http://www.uac.bj/ Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Calavi Université d'Agriculture Benin Plateau http://www.uakbenin.or No No No No No No de Kétou g/ Université Catholique Benin Littoral http://www.ucao-uut.tg/ No No No No No No de l'Afrique de l'Ouest Université de Parakou Benin Borgou site cannot be reached No Yes Yes No No No Moïsi J, et al. -

Indigenous Knowledge Practices Employed by Small Holder Farmers in Kagadi District, Kibaale Sub-Region, Uganda

Advance Research Journal of Multi-Disciplinary Discoveries I Vol. 25.0 I Issue – I ISSN NO : 2456-1045 INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE PRACTICES EMPLOYED BY SMALL HOLDER FARMERS IN KAGADI DISTRICT, KIBAALE SUB-REGION, UGANDA Original Research Article ABSTRACT ISSN : 2456-1045 (Online) (ICV-AGS/Impact Value): 63.78 (GIF) Impact Factor: 4.126 This paper identifies the use of indigenous knowledge Publishing Copyright @ International Journal Foundation by small holder farmers in Kagadi district of Kibaale Journal Code: ARJMD/AGS/V-25.0/I-1/C-7/MAY-2018 sub-region in South Western Uganda. The farmers here practice diverse farming systems and 51% practice either Category : AGRICULTURAL SCIENCE Volume : 25.0 / Chapter- VII / Issue -1 (MAY-2018) mixed farming and / or intercropping. Journal Website: www.journalresearchijf.com The results clearly show that 67% of the small holder Paper Received: 19.04.2018 farmers still use indigenous knowledge in farming. 62% Paper Accepted: 27.05.2018 of the technical persons believe that food production and Date of Publication: 10-06-2018 sustainability is due to use of indigenous agricultural Page: 46-58 knowledge by the local people of the rural communities carrying out mixed farming 71.8% grow crops and also look after domestic animals simultaneously. But all of them (100%) use indigenous knowledge in managing diseases and selection of seeds for planting the following season. They use indigenous knowledge in food security by growing “hard” crops like maize, cassava and beans. These crops have been turned into commercial crops which was not the primary intention originally. Name of the Author: They still practice indigenous knowledge in produce quantity and quality, in disease control, in agro- Dr. -

Research4life Academic Institutions

Research4Life Academic Institutions Filter Summary Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Bamyan Bamyan University Charikar Parwan University Cheghcharan Ghor Institute of Higher Education Ferozkoh Ghor university Gardez Paktia University Ghazni Ghazni University HERAT HERAT UNIVERSITY Herat Institute of Health Sciences Ghalib University Jalalabad Nangarhar University Alfalah University Kabul Afghan Medical College Kabul 20-Apr-2018 9:40 AM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 1 of 174 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Kabul JUNIPER MEDICAL AND DENTAL COLLEGE Government Medical College Kabul University. Faculty of Veterinary Science Aga Khan University Programs in Afghanistan (AKU-PA) Kabul Dental College, Kabul Kabul University. Central Library American University of Afghanistan Agricultural University of Afghanistan Kabul Polytechnic University Kabul Education University Kabul Medical University, Public Health Faculty Cheragh Medical Institute Kateb University Prof. Ghazanfar Institute of Health Sciences Khatam al Nabieen University Kabul Medical University Kandahar Kandahar University Malalay Institute of Higher Education Kapisa Alberoni University khost,city Shaikh Zayed University, Khost 20-Apr-2018 9:40 AM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 2 of 174 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Lashkar Gah Helmand University Logar province Logar University Maidan Shar Community Midwifery School Makassar Hasanuddin University Mazar-e-Sharif Aria Institute of Higher Education, Faculty of Medicine Balkh Medical Faculty Pol-e-Khumri Baghlan University Samangan Samanagan University Sheberghan Jawzjan university Albania Elbasan University "Aleksander Xhuvani" (Elbasan), Faculty of Technical Medical Sciences Korca Fan S. Noli University, School of Nursing Tirana University of Tirana Agricultural University of Tirana 20-Apr-2018 9:40 AM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 3 of 174 Country City Institution Name Albania Tirana University of Tirana. -

Gulu University Office of the Academic Registrar Admissions List for 2016/2017 Academic Year

GULU UNIVERSITY OFFICE OF THE ACADEMIC REGISTRAR ADMISSIONS LIST FOR 2016/2017 ACADEMIC YEAR DIPLOMA ENTRY SCHEME GULU UNIVERSITY MAIN CAMPUS STUDENTS ADMITTED UNDER GOVERNEMENT SPONSORSHIP BACHELOR OF MEDICINE AND BACHELOR OF SURGERY (GUM) NO. NAME SEX DISTRICT DIPLOMA YEAR INSTITUTION DIPLOMA IN CLINICAL MED. AND GULU SCHOOL OF CLINICAL 1 AKUKU JAMES M ADJUMANI 2007 COM. HEALTH OFFICERS DIPLOMA IN CLINICAL MED. AND MEDICARE HEALTH 2 BIYINZIKA NORAH MARY F WAKISO 2015 COM. HEALTH PROFESSIONALS COLLEGE DIPLOMA IN CLINICAL MED. AND MBALE SCHOOL OF CLINICAL 3 DRAMADRI ALEX M YUMBE 2012 COM. HEALTH OFFICERS DIPLOMA IN CLINICAL MED. AND FORT PORTAL SCHOOL OF 4 OGWAL JOHN BAPTIST M ALEBTONG 2010 COM. HEALTH CLINICAL OFFICERS DIPLOMA IN CLINICAL MED. AND GULU SCHOOL OF CLINICAL 5 OJOK ISAAC ODONGO M APAC 2013 COM. HEALTH OFFICERS BACHELOR OF SCIENCE EDUCATION (PHYSICAL) (WEEKDAY) - SEG NO. NAME SEX DISTRICT DIPLOMA YEAR INSTITUTION DIPLOMA IN WATER AND UGANDA TECHNICAL 1 MUSINGUZI JOHNSON M KYENJOJO SANITATION ENGINEERING 2014 COLLEGE - KICHWAMBA (PHY/MAT) DIPLOMA IN EDUCATION 2 OGWANG ROBERT M OTUKE 2013 KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY SECONDARY (PHY/MAT) BACHELOR OF SCIENCE EDUCATION (ECONOMICS) (WEEKDAY) - GEE NO. NAME SEX DISTRICT DIPLOMA YEAR INSTITUTION DIPLOMA IN BUSINESS STUDIES 1 OCAATRE INNOCENT M MARACHA 2012 MUBS (ECO/GEO) BACHELOR OF SCIENCE EDUCATION (BIOLOGICAL) (WEEKDAY) - GBE NO. NAME SEX DISTRICT DIPLOMA YEAR INSTITUTION DIPLOMA IN EDUCATION 1 ODONGO FREDERICK M OYAM 2001 KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY SECONDARY (BIO/GEO) BACHELOR OF SCIENCE EDUCATION (SPORTS SCIENCE) (WEEKDAY) - GSS NO. NAME SEX DISTRICT DIPLOMA YEAR INSTITUTION 1 OTTO DICK ODONG M GULU DIPLOMA IN ANIMAL PRODUCTION 2015 BUSITEMA UNIVERSITY BACHELOR OF QUANTITATIVE ECONOMICS (WEEKDAY) (GQE) NO. -

North South Cooperation by Academics and Academic Institutions.Pdf

North south cooperation by academics and academic institutions: The case of Uganda A.B.K.Kasozi, PhD (California) Research Associate, Makerere Institute of Social Research Former Executive Director, National Council for Higher Education, Uganda. 1. Introduction As latecomers in the establishment of knowledge creation centres (universities, polytechnics and research centres), African higher education institutions need to collaborate with universities in regions and states that have had these institutions for centuries. But this cooperation must be well defined and all areas of cooperation known to each party. Past macro cooperation was often given in donor/aid recipient frameworks and often increased the dependency of southern partners to the north. Therefore, the levels, types and methods of co-operation must be thoroughly defined to avoid the mistakes of the past. The ideal mode of cooperation, which may not be achieved immediately, should be based on the following ten mark stones. First, both partners must do the designing of any joint research or teaching project cooperatively. The southern partner must make sure that the project will create knowledge that is useful to his/her constituency in the south. Africa needs, like the north did in its process of development, home focused and home-grown knowledge and thinkers who can use local conceptual models to resolve local problems. Secondly, both partners must have the capacity to, and should, contribute equal intellectual inputs in the designing of a project. People of unequal intellectual levels are unlikely to work well together. Thirdly, the partners must share the execution of the project. Each party should be assigned areas of work and the targets to be achieved at given time frames. -

Let It Come from the Peopleâ•Š: Exploring Decentralization, Participatory Processes, and Community Empowerment in West

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2013 "Let It Come From the People”: Exploring Decentralization, Participatory Processes, and Community Empowerment in Western, Rural Uganda Rachel Harmon SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Growth and Development Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Rural Sociology Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Harmon, Rachel, ""Let It Come From the People”: Exploring Decentralization, Participatory Processes, and Community Empowerment in Western, Rural Uganda" (2013). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1689. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1689 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Let It Come From the People”: Exploring Decentralization, Participatory Processes, and Community Empowerment in Western, Rural Uganda Rachel Harmon SIT Uganda Development Studies Fall 2013 Advisors: Mr. MwalimuMusheshe and Dr. Charlotte Mafumbo Location: Kibaale District, Uganda Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the patient, extensive, and gracious assistance and insight of many individuals and organizations. The researcher would like to first thank Uganda Rural Development Training Programme (URDT) for providing her with the opportunity to conduct this research, for organizing a truly amazing research design, and for supporting her throughout the research period.