Racing, Region, and the Environment: a History of American Motorsports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holiday Catalog 2015 – 2016 R Cool Pe D U V S D S

Holiday Catalog 2015 – 2016 r Cool pe D u V S D s ! S EE PAGE 7 Reading for Racers Hot New Titles Most Popular This Year A HISTORY OF AUTO RACING Brand New from Coastal 181! IN NEW ENGLAND Vol. 1 FOYT, ANDRETTI, PETTY A Project of the North East America’s Racing Trinity Motor Sports Museum by Bones Bourcier An extraordinary compendium of the rich Were A.J. Foyt, Mario Andretti, and Richard Petty the history of stock-car, open-wheel, drag and three best racers in our nation’s history? Maybe yes, road racing in New England. Full of maybe no. But in weaving together their complex personal stories of drivers and tracks illustrated with tales, and examining the social and media climates of hundreds of photos, all contributed for the benefit of the their era, award-winning author Bones Bourcier shows North East Motor Sports Museum. Hard cover, 304 pp., why their names are still synonymous with the sport they carried to 400+ B&W photos. S-1405: $34.95 new heights. If you buy one racing book as a present, this should be it! Hard Cover, 288 pp., B&W photos. S-1500: $34.95 THE PEOPLE’S CHAMP A Racing Life Back by Popular Demand! by Dave Darland with Bones Bourcier The memoir of one of Sprint Car racing’s LANGHORNE! No Man’s Land most popular and talented racers, a by L. Spencer Riggs champion in all three of USAC’s national Reprinted at last, with all the original content, this divisions—Silver Crown, Sprint Cars, and award-winning volume covers the entire history of the Midgets—and still winning! Soft cover, 192 pp., world’s toughest mile, fr om its inception in 1926 to its 32 pp. -

Aug 2010.Pdf

July - August 2010 www.superbirdclub.com email: [email protected] Pete Hamilton Superbird Restoration Petty’s Garage in Level Cross North Carolina has unveiled their restoration of Pete Hamilton’s 1970 Daytona 500 winning Superbird race car. The car is owned by collector Todd Werner, who also owns a Petty 1971 Road Runner among quite a few other significant cars. At left in the group photo, you can see The King behind the car. Left of him is Dale Inman, and at the windshield pillar is Pete Hamilton crew chief, Richie Barsz. I am told that Richie was instrumental in visually identifying the car. Owner Todd Werner is second from left. There is not a lot of information about the history of the car that has been released publicly at this time. I am told that after 1970, the car was reportedly sold to privateer Doc Faustina , who entered it as a 1970 Road Runner in select Grand National races, s during 1971 and 1972. In later years, it was rebodied as a newer Charger and continued to race into the mid 1970’s. I hope to bring you more information about the car soon. At middle left, Richard is checking out the Maurice Petty built Hemi. You can see the car is still being lettered. Immediately after these photos were taken, the car was loaded up and headed for the Mopar Nationals in Columbus where it was on display in the Manufacturers Midway. Petty’s Garage is a specialty restoration facility operating from the former Petty Enterprises shops. 2010 Events Calendar page 2 September 9th-12th St Louis MO - Monster Mopar Weekend & Aero Car Display This event is coming up next month. -

Springfield Illinois the 2016 Be Held in Springfield in Conjunction with the International Route 66 Mother Road Festival

Feb-Mar-April 2016 www.superbirdclub.com email: [email protected] 2016 National Meet - September 20-25th, Springfield Illinois The 2016 be held in Springfield in conjunction with the International Route 66 Mother Road Festival. Our hosts are Sherri and Bill Peddicord. This will be a joint meet between the Winged Warriors group and DSAC. Members of the Dodge Charger Registry are also invited as it is the 50th anniversary of the Charger. The Festival Car show is Sept 23-25. The big show day is Saturday and the big cruise on Friday night. Sunday is a wind down day. So if you need to head home, no problem. Attendance each year exceeds 1000 cars . It is in Downtown Springfield Centering around the Old State Capital building. http://www.familyevents.com/international-route-66-mother-road-festival This is the link for the car show registration. Pre-registration is $40 and we get a $5 discount. They do include a t-shirt with the pre-registration. The pre-registration deadline is Sept 16. After that on Site registration is $55. Include “Superbird Club” on your registration form for the discount. The hotel that we have a room block is The Carpenter Street Hotel. It is similar to a Comfort Inn or Hampton Inn style. It is two blocks from the Abraham Lincoln Museum and about five blocks from the car show area. Several downtown restaurants are close by. If you plan to attend please make your reservations now. The Carpenter Street Hotel 217-789-9100 or 800-779-9200 525 North 6th Street www.carpenterstreethotel.com Springfield IL 62702 Room rate is $ 94.00 for Double Queen or King Rooms. -

Fedex Racing Press Materials 2013 Corporate Overview

FedEx Racing Press Materials 2013 Corporate Overview FedEx Corp. (NYSE: FDX) provides customers and businesses worldwide with a broad portfolio of transportation, e-commerce and business services. With annual revenues of $43 billion, the company offers integrated business applications through operating companies competing collectively and managed collaboratively, under the respected FedEx brand. Consistently ranked among the world’s most admired and trusted employers, FedEx inspires its more than 300,000 team members to remain “absolutely, positively” focused on safety, the highest ethical and professional standards and the needs of their customers and communities. For more information, go to news.fedex.com 2 Table of Contents FedEx Racing Commitment to Community ..................................................... 4-5 Denny Hamlin - Driver, #11 FedEx Toyota Camry Biography ....................................................................... 6-8 Career Highlights ............................................................... 10-12 2012 Season Highlights ............................................................. 13 2012 Season Results ............................................................... 14 2011 Season Highlights ............................................................. 15 2011 Season Results ............................................................... 16 2010 Season Highlights. 17 2010 Season Results ............................................................... 18 2009 Season Highlights ........................................................... -

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0001 Victory Circle #4012, WG 1951 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0002 1959 Sports Car Grand Prix Weekend 1959 D-0003 A Gullwing at Twilight 1959 D-0004 At the IMRRC The Legacy of Briggs Cunningham Jr. 1959 D-0005 Legendary Bill Milliken talks about "Butterball" Nov 6,2004 1959 D-0006 50 Years of Formula 1 On-Board 1959 D-0007 WG: The Street Years Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1948 D-0008 25 Years at Speed: The Watkins Glen Story Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1972 D-0009 Saratoga Automobile Museum An Evening with Carroll Shelby D-0010 WG 50th Anniversary, Allard Reunion Watkins Glen, NY D-0011 Saturday Afternoon at IMRRC w/ Denise McCluggage Watkins Glen Watkins Glen October 1, 2005 2005 D-0012 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival Watkins Glen 2005 D-0013 1952 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen 1952 D-0014 1951-54 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1951-54 D-0015 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend 1952 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1952 D-0016 Ralph E. Miller Collection Watkins Glen Grand Prix 1949 Watkins Glen 1949 D-0017 Saturday Aternoon at the IMRRC, Lost Race Circuits Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 2006 D-0018 2005 The Legends Speeak Formula One past present & future 2005 D-0019 2005 Concours d'Elegance 2005 D-0020 2005 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival, Smalleys Garage 2005 D-0021 2005 US Vintange Grand Prix of Watkins Glen Q&A w/ Vic Elford 2005 D-0022 IMRRC proudly recognizes James Scaptura Watkins Glen 2005 D-0023 Saturday -

![1962-06-07, [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9191/1962-06-07-p-789191.webp)

1962-06-07, [P ]

. Thursday, Jun* 7, 1962 \ AUTOMOBILES AUTOMOBILES AUTOMOBILES AUTOMOBILES |..... 'automobTles AUTOMOBILES AUTOMOBILES AUTOMOBILES AUTOMOBILES COME TO L J. TROTTER CLEVELAND’S NEWEST MILT 4 MILLER IS CELEBRATING FOR I CHRYSLER DEALER 29th »™. - FIRECRACKER HIS Anniversary IS 4,h ”Ju,y ' SALE! b TO MOVE 121 FACTORY FRESH PONTIACS CUTTING PRICES! All Reconditioned and Ready For MUei and Miles of Carefree •? THIS MONTH THROUGH TO JULY 4th WE ARE Summer Driving On All 1962 1960 THUNDERBIRD Hardtop Cruisomatic, CUTTING OUR PRICES TO THE BONE!! Radio, Heater, Power Steering and Brakes, “■sVVV Plymouth:, Valiants and Chryslers excellent throughout. 1961 FORD Fairlane 2-Door, fully factory Qi AAE WE ARE READY TO DEAL! equipped with economical 6- cyl. engine ’•'InUV Bring Your Title With You WE WILL NOT BE UNDERSOLD and standard transmission. 1960 FALCON 2-Door Sedan. LISTED BELOW IS WHAT WE HAVE IN STOCK AND COMING Fordomatic, Radio and Heater, $1395 1962 PLYMOUTH $1Q7Q I IN THIS MONTH FROM THE FACTORY 1960 FORD 4-Door Sedan. V-8, NEW FULL SIZE 2-DR. SEDANS IO// I Fordomatic, Radio, Heater. Solid white $1395 finish. Excellent throughout. Including Torsion-Aire Suspension, Safety Rim Wheels, and Alternator AT NO EXTRA COST! 1960 CORVAIR 4-Door. Fully factory S19Q*! 129 BRAND NEW equipment plus Powerglide Tran>mission. Tutone finish. COME IN AND SEE US FOR 1959 FORD Custom "300" 4-Door. Economical 6-cyl. Engine with Standard $1095 High-Trade Allowance 1962 PONTIACS Transmission, Radio and Heater. A-1 throughout. 4 1958 BUICK Riviera 2-Door Hardtop. Dynaflow, Radio, Heater, Power Steering S1095 KEITH-WE1GLE MOTORS, INC TO BE SOLD THIS MONTH! and Brakes. -

Holiday Catalog 2014 – 2015 R Cool Pe D U V S D S

Holiday Catalog 2014 – 2015 r Cool pe D u V S D s ! S EE PAGE 7 Reading for Racers Hot New Titles Most Popular This Year WICKED FAST Racing Through YBrand New from Coastal 181 Life with Bentley Warren by Bones Bourcier THE PEOPLE’S CHAMP One of the most decorated short-track A Racing Life drivers ever, seven-time Oswego Speedway by Dave Darland with Bones Bourcier champion, four-time ISMA champ, two-time The memoir of one of Sprint Car racing ’s most popular Little 500 winner, Indy and Silver Crown and talented racers, a champion in all three of USAC’s star—Bentley Warren is also a self-taught entrepreneur, merry national divisions—Silver Crown, Sprint Cars, and saloon-keeper, tricked-out Harley rider, and overall hell-raiser Midgets—and still winning! Soft cover, 192 pp., with a heart. Soft cover, 272 pp., B&W photos. S-1322: $29.95 32 pp. of B&W and color photos. S-1376: $24.95 DID YOU SEE THAT? A HISTORY OF AUTO RACING Unforgettable Moments in IN NEW ENGLAND Vol. 1 Midwest Open-Wheel Racing by Joyce Standridge A Project of the North East Motor Sports Museum The drama, joy, and sometimes terror that There’s never been a racing book like this. If it was in is open-wheel racing, captured by some of the best photogra - New England, on the boards, the drag strips, or if it’s phers in the country and illuminated by writer and open-wheel about Midgets, Sprints, Modifieds, or Late Models on expert Joyce Standridge. -

HEMI Milestones

Contact: General Media Inquiries Bryan Zvibleman HEMI® Milestones A Journey through a Remarkable Engine’s Remarkable History August 10, 2005, Auburn Hills, Mich. - 1939 Chrysler begins design work on first HEMI®, a V-16 for fighter aircraft. 1951 Chrysler stuns automotive world with 180 hp HEMI V-8 engine. Chrysler New Yorker convertible paces Indianapolis 500 race. Saratoga first in Stock Car Class; second overall in Carrera Pan-American road race. Briggs Cunningham chooses HEMI engines for his Le Mans race cars. 1952 A special HEMI is tested in a Kurtis Kraft Indy roadster; it’s banned by racing officials as too fast. 1953 Lee Petty’s HEMI Dodge wins five NASCAR races and finishes second in championship points. Cunningham’s C-4R HEMI wins 12 Hours of Sebring and finishes third at Le Mans. A Dodge HEMI V-8 breaks 196 stock car records at Bonneville Salt Flats. 1954 A Chrysler HEMI with four-barrel and dual exhausts makes 235 hp. Lee Petty wins Daytona Beach race in a Chrysler HEMI. Lee Petty wins NASCAR Grand National championship driving Chrysler and Dodge HEMIs. Cunningham HEMIs win Sebring again, third and fifth at Le Mans. Dodge Red Ram HEMI convertible paces Indy 500. 1955 Chrysler introduces the legendary 300 as America’s most powerful stock car. Chrysler 300 with dual four-barrel 331 c.i.d. HEMI is first production car to make 300 hp. A Carl Kiekhaefer-prepared Chrysler 300 wins at Daytona Beach with Tim Flock driving. Chrysler bumps HEMI to 250 hp in New Yorker and 280 hp in Imperial. -

Mar-Apr 1984

March Sfienty April 1984 In 1979, Union Oil made the first dis- The Helm field, the first discovered, covery of oil offshore the Netherlands. is now producing from flve wells with IIri'i When this was followed by a second a sixth nearing completion. The discovery in 1980, commercial pro- Helder field produces from 12 wells. duction became a possibility-but And the Hoorn fleld, discovered in IVETHERLAIVDS only if the costs of development could 1982, produces from six wells. Costs be tightly controlled. incurred so far in the development The target date for production of of the Q/1 fields are in excess of one ll[[Sllm[ first oil was set for October 1982. Computer projections rated the 3lalil:n,gTud:d:xr:I:Cncgoer:i:egatvoe:aaguegsh- chances for such rapid completion of development very low, but this was to i`oTl::t,threegullderstooneus alongtime be no ordinary development process. The fields are all on the Q/I block, Working in close cooperation with its where Union has an 80 percent inter- C0mln joint-venture partner Nedlloyd, the est. The block covers about 75,000 Dutch government and Dutch contrac- acres and still has potential for new tors, Union beat the odds. discoveries, according to H. D. Max- wllHH First oil was produced in Septem- well, Union's regional vice president ber 1982 from the Helm and Helder headquartered in London. 'tsince 1967 Union and Nedlloyd fields, slightly ahead of schedule. The wail Hoom field began producing in August 1983, more than a month }9a,`;eo3C#:)do°fv;:oLp5fpe°ca°ryh::,i:::rs ahead of a very ambidous schedule. -

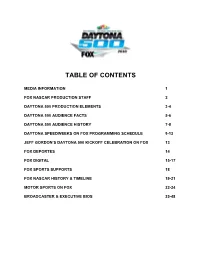

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION 1 FOX NASCAR PRODUCTION STAFF 2 DAYTONA 500 PRODUCTION ELEMENTS 3-4 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE FACTS 5-6 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE HISTORY 7-8 DAYTONA SPEEDWEEKS ON FOX PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE 9-12 JEFF GORDON’S DAYTONA 500 KICKOFF CELEBRATION ON FOX 13 FOX DEPORTES 14 FOX DIGITAL 15-17 FOX SPORTS SUPPORTS 18 FOX NASCAR HISTORY & TIMELINE 19-21 MOTOR SPORTS ON FOX 22-24 BROADCASTER & EXECUTIVE BIOS 25-48 MEDIA INFORMATION The FOX NASCAR Daytona 500 press kit has been prepared by the FOX Sports Communications Department to assist you with your coverage of this year’s “Great American Race” on Sunday, Feb. 21 (1:00 PM ET) on FOX and will be updated continuously on our press site: www.foxsports.com/presspass. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to provide further information and facilitate interview requests. Updated FOX NASCAR photography, featuring new FOX NASCAR analyst and four-time NASCAR champion Jeff Gordon, along with other FOX on-air personalities, can be downloaded via the aforementioned FOX Sports press pass website. If you need assistance with photography, contact Ileana Peña at 212/556-2588 or [email protected]. The 59th running of the Daytona 500 and all ancillary programming leading up to the race is available digitally via the FOX Sports GO app and online at www.FOXSportsGO.com. FOX SPORTS ON-SITE COMMUNICATIONS STAFF Chris Hannan EVP, Communications & Cell: 310/871-6324; Integration [email protected] Lou D’Ermilio SVP, Media Relations Cell: 917/601-6898; [email protected] Erik Arneson VP, Media Relations Cell: 704/458-7926; [email protected] Megan Englehart Publicist, Media Relations Cell: 336/425-4762 [email protected] Eddie Motl Manager, Media Relations Cell: 845/313-5802 [email protected] Claudia Martinez Director, FOX Deportes Media Cell: 818/421-2994; Relations claudia.martinez@foxcom 2016 DAYTONA 500 MEDIA CONFERENCE CALL & REPLAY FOX Sports is conducting a media event and simultaneous conference call from the Daytona International Speedway Infield Media Center on Thursday, Feb. -

IPG Spring 2020 Auto & Motorcycle Titles

Auto & Motorcycle Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} The Brown Bullet Rajo Jack's Drive to Integrate Auto Racing Bill Poehler Summary The powers-that-be in auto racing in the 1920s, namely the American Automobile Association’s Contest Board, prohibited everyone who wasn’t a white male from the sport. Dewey Gaston, a black man who went by the name Rajo Jack, broke into the epicenter of racing in California, refusing to let the pervasive racism of his day stop him from competing against entire fields of white drivers. In The Brown Bullet, Bill Poehler uncovers the life of a long-forgotten trailblazer and the great lengths he took to even get on the track, and in the end, tells how Rajo Jack proved to a generation that a black man could compete with some of the greatest white drivers of his era, wining some of the biggest races of the day. Lawrence Hill Books 9781641602297 Pub Date: 5/5/20 Contributor Bio $28.99 USD Bill Poehler is an award-winning investigative journalist based in the northwest, where he has worked as a Discount Code: LON Hardcover reporter for the Statesman Journal for 21 years. His work has appeared in the Oregonian, the Eugene Register-Guard and the Corvallis Gazette-Times ; online at OPB.org and KGW.com; and in magazines including 240 Pages Carton Qty: 0 Slant Six News , Racing Wheels , National Speed Sport News and Dirt Track Digest . He lives in Salem, Oregon. Biography & Autobiography / Cultural Heritage BIO002010 9 in H | 6 in W How to be Formula One Champion Richard Porter Summary Are you the next Lewis Hamilton? How to be F1 Champion provides you with the complete guide to hitting the big time in top-flight motorsport, with advice on the correct look, through to more advanced skills such as remembering to insert 'for sure' at the start of every sentence, and tips on mastering the accents most frequently heard at press conferences. -

January (Winter) 2019

IAPSNJ Quarterly Magazine January ~ March 2019 Winter Edition Issue No. 41 A social, fraternal organization of more than 4,000 Italian American Law Enforcement officers in the State. William Schievella, President Editor-in-Chief Patrick Minutillo Visit us at http://www.iapsnj.org IAPSNJ Quarterly Magazine January ~ March 2019 Winter Edition Page 2 Issue No 41 P RESIDENT’ S MESSAGE B ILL S CHIEVELLA Detective Thomas officers for recognition at our SanFilippo, Jersey City Dinner Meetings directly to Police Department and me. We enjoy recognizing Officer Alex Monteleone, those that have gone above Palisades Park Police and beyond as law Department to the Board of enforcement officers. I can Officers. These five new be reached at board members are a great [email protected] addition to the current board I want to wish you and As you read this magazine of highly dedicated law your families a Healthy and we will be about to ring in the enforcement officers. Happy New Year. Please join New Year. For many of us, Organization’s like ours are us at a meeting or event in 2018 was full of vital because of the constant the coming year. accomplishments and influx of new talent to meet celebrations. This is the time the needs of our group. As of the year where we enjoy this Executive Board Fraternally yours, celebrating with colleagues, continues to serve the Italian William Schievella, President family and friends. As American and law Christmas and Hanukkah enforcement communities, I pass by us and the New Year always invite new members begins let’s use this as a time to become more involved.