Juan Mario Diaz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Josemaría Escrivá De Balaguer En Santiago De Chile (1974) María Eugenia Ossandón Widow

STUDIA ET DOCUMENTA RIvista DEll’Istituto Storico San JosemaríA Escrivá VOL. 11 - 2017 ISTITUTO STORICO SAN JOSEMARíA ESCRIvá - ROMA Sommario Mons. Javier Echevarría (1932-2016): In memoriam José Luis Illanes . 7 San Josemaría Escrivá in America Latina, 1974-1975 Presentación María Isabel Montero Casado de Amezúa . 15 América Latina en el siglo XX: religión y política Carmen-José Alejos Grau . 19 I viaggi di catechesi in America Latina di Josemaría Escrivá. Uno sguardo d’insieme (1974-1975) Carlo Pioppi . 49 Com os braços abertos a todos. A visita de São Josemaria Escrivá ao Brasil Alexandre Antosz Filho . 65 Josemaría Escrivá de Balaguer en Santiago de Chile (1974) María Eugenia Ossandón Widow . 101 Studi e note Orígenes y primera historia de Villa Tevere. Los edificios de la sede central del Opus Dei en Roma (1947-1960) Alfredo Méndiz . 153 La editorial Minerva (1943-1946). Un ensayo de cultura popular y cristiana de las primeras mujeres del Opus Dei Mercedes Montero . 227 ISSN 1970-4879 SetD 11 (2017) 3 Documenti Los primeros pasos del Opus Dei en Italia. Epistolario entre Roma y Madrid (noviembre 1942 – febrero 1943) Fernando Crovetto . 267 Notiziario Conferencias sobre el Opus Dei en el ámbito académico ........... .317 Sezione bibliografica Nota bibliografica Raimon Panikkar: a propósito de una biografía Josep-Ignasi Saranyana . 323 Recensioni Pilar Río, Los fieles laicos, Iglesia en la entraña del mundo . Reflexión teológica sobre la identidad eclesial de los laicos en un tiempo de nueva evangelización (María Eugenia Ossandón W .) . 349 Jesús Sevilla Lozano, Miguel Fisac . ¿Arquitecto de Dios o del ‘Diablo’? (Santiago Martínez Sánchez) . -

Libro ING CAC1-36:Maquetación 1.Qxd

© Enrique Montesinos, 2013 © Sobre la presente edición: Organización Deportiva Centroamericana y del Caribe (Odecabe) Edición y diseño general: Enrique Montesinos Diseño de cubierta: Jorge Reyes Reyes Composición y diseño computadorizado: Gerardo Daumont y Yoel A. Tejeda Pérez Textos en inglés: Servicios Especializados de Traducción e Interpretación del Deporte (Setidep), INDER, Cuba Fotos: Reproducidas de las fuentes bibliográficas, Periódico Granma, Fernando Neris. Los elementos que componen este volumen pueden ser reproducidos de forma parcial siem- pre que se haga mención de su fuente de origen. Se agradece cualquier contribución encaminada a completar los datos aquí recogidos, o a la rectificación de alguno de ellos. Diríjala al correo [email protected] ÍNDICE / INDEX PRESENTACIÓN/ 1978: Medellín, Colombia / 77 FEATURING/ VII 1982: La Habana, Cuba / 83 1986: Santiago de los Caballeros, A MANERA DE PRÓLOGO / República Dominicana / 89 AS A PROLOGUE / IX 1990: Ciudad México, México / 95 1993: Ponce, Puerto Rico / 101 INTRODUCCIÓN / 1998: Maracaibo, Venezuela / 107 INTRODUCTION / XI 2002: San Salvador, El Salvador / 113 2006: Cartagena de Indias, I PARTE: ANTECEDENTES Colombia / 119 Y DESARROLLO / 2010: Mayagüez, Puerto Rico / 125 I PART: BACKGROUNG AND DEVELOPMENT / 1 II PARTE: LOS GANADORES DE MEDALLAS / Pasos iniciales / Initial steps / 1 II PART: THE MEDALS WINNERS 1926: La primera cita / / 131 1926: The first rendezvous / 5 1930: La Habana, Cuba / 11 Por deportes y pruebas / 132 1935: San Salvador, Atletismo / Athletics -

Redalyc.History of the Colombian Left-Wings Between 1958 and 2010

Revista Tempo e Argumento E-ISSN: 2175-1803 [email protected] Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina Brasil Archila, Mauricio; Cote, Jorge History of the Colombian left-wings between 1958 and 2010 Revista Tempo e Argumento, vol. 7, núm. 16, septiembre-diciembre, 2015, pp. 376-400 Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina Florianópolis, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=338144734018 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative e ‐ ISSN 2175 ‐ 1803 History of the Colombian left‐wings between 1958 and 20101 Abstract This article looks at the history of left‐wings in Colombia, Mauricio Archila framed within what was happening in the country, Latin Ph.D. and Professor in the Graduate program at America, and the world between 1958 and 2010. After the Universidad Nacional, in Bogotá, and specifying what we mean by “left‐wings” and outlining their associate researcher of the CINEP. background in the first half of the 20th century, there is a Colombia. panorama of five great moments of the period under study to [email protected] reach the recent situation. The chronology favors the internal aspects of the history of Colombian left‐wings, allowing us to appreciate their achievements and limitations framed into Jorge Cote such a particular context as the Colombian one. MA student in History at the Universidad Nacional, in Bogotá. Keywords: Colombia; Left‐wings; Guerrillas; Social Colombia. -

The Role of Health Technology Assessment in the European Union

European on Health Systems and Policies ENSURING VALUE FOR MONEY IN HEALTH CARE The role of health technology assessment in the European Union Corinna Sorenson, Michael Drummond, Panos Kanavos Observatory Studies Series No 11 Ensuring value for money in health care The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies supports and promotes evidence- based health policy-making through comprehensive and rigorous analysis of health systems in Europe. It brings together a wide range of policy-makers, academics and practitioners to analyse trends in health reform, drawing on experience from across Europe to illuminate policy issues. The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies is a partnership between the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, the Governments of Belgium, Finland, Greece, Norway, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden, the Veneto Region of Italy, the European Investment Bank, the Open Society Institute, the World Bank, the London School of Economics and Political Science and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Ensuring value for money in health care The role of health technology assessment in the European Union Corinna Sorenson Michael Drummond Panos Kanavos Keywords: TECHNOLOGY ASSESSMENT, BIOMEDICAL – organization and administration OUTCOME AND PROCESS ASSESSMENT (HEALTH CARE) EVIDENCE-BASED MEDICINE DECISION MAKING COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS EUROPEAN UNION © World Health Organization 2008, on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies All rights reserved. The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies welcomes requests for permission to reproduce or translate its publications, in part or in full. Address requests about publications to: Publications, WHO Regional Office for Europe, Scherfigsvej 8 DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark Alternatively, complete an online request form for documentation, health information, or for permission to quote or translate, on the Regional Office web site (http://www.euro.who.int/pubrequest). -

Langues, Accents, Prénoms & Noms De Famille

Les Secrets de la Septième Mer LLaanngguueess,, aacccceennttss,, pprréénnoommss && nnoommss ddee ffaammiillllee Il y a dans les Secrets de la Septième Mer une grande quantité de langues et encore plus d’accents. Paru dans divers supplément et sur le site d’AEG (pour les accents avaloniens), je vous les regroupe ici en une aide de jeu complète. D’ailleurs, à mon avis, il convient de les traiter à part des avantages, car ces langues peuvent être apprises après la création du personnage en dépensant des XP contrairement aux autres avantages. TTaabbllee ddeess mmaattiièèrreess Les différentes langues 3 Yilan-baraji 5 Les langues antiques 3 Les langues du Cathay 5 Théan 3 Han hua 5 Acragan 3 Khimal 5 Alto-Oguz 3 Koryo 6 Cymrique 3 Lanna 6 Haut Eisenör 3 Tashil 6 Teodoran 3 Tiakhar 6 Vieux Fidheli 3 Xian Bei 6 Les langues de Théah 4 Les langues de l’Archipel de Minuit 6 Avalonien 4 Erego 6 Castillian 4 Kanu 6 Eisenör 4 My’ar’pa 6 Montaginois 4 Taran 6 Ussuran 4 Urub 6 Vendelar 4 Les langues des autres continents 6 Vodacci 4 Les langages et codes secrets des différentes Les langues orphelines ussuranes 4 organisations de Théah 7 Fidheli 4 Alphabet des Croix Noires 7 Kosar 4 Assertions 7 Les langues de l’Empire du Croissant 5 Lieux 7 Aldiz-baraji 5 Heures 7 Atlar-baraji 5 Ponctuation et modificateurs 7 Jadur-baraji 5 Le code des pierres 7 Kurta-baraji 5 Le langage des paupières 7 Ruzgar-baraji 5 Le langage des “i“ 8 Tikaret-baraji 5 Le code de la Rose 8 Tikat-baraji 5 Le code 8 Tirala-baraji 5 Les Poignées de mains 8 1 Langues, accents, noms -

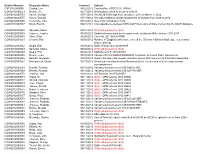

Control Number Requester Name Scanned Subject CNT2012000005 Guidos, Lori 06/22/2012 Contract No

Control Number Requester Name Scanned Subject CNT2012000005 Guidos, Lori 06/22/2012 Contract No. HSSCCG11J00088 COW2012000553 Melton, K.E. 05/31/2012 Information related to Vacancy 624276 COW2012000554 Vance, Donald 05/31/2012 All USCIS FOIA logs from January 1, 2011 to March 1, 2012 COW2012000555 Vance, Donald 05/31/2012 Records relating to all USCIS payment to Verizon from 2009 to 2010 COW2012000556 Ciccarone, Lilin 05/16/2012 New York Immigration Fund COW2012000557 Mock, Brentin 06/01/2012 Correspondence between DHS and Fl Secretary of State concerning the SAVE database COW2012000558 Zamudio, Maria 06/01/2012 Withheld pursuant to (b)(6) COW2012000559 Holmes, Jennifer 06/05/2012 Statistical Information on decsions made by Asylum Officers from 1991-2011 COW2012000560 Viker, Elliot 06/05/2012 Case No. 201106424 PRMI COW2012000561 Choucri, Mai 06/06/2012 Number of Egyptians who have entered the US from 1990 to include age, sex, marital status, and city COW2012000562 Siegal, Erin 06/06/2012 DOS referral Case 201001905 COW2012000563 Zamudio, Maria 06/06/2012 Withheld pursuant to (b)(6) COW2012000564 Siegal, Erin 06/06/2012 DOS Referral F-2010-00014 COW2012000565 Newell, Jean 06/07/2012 Vacancy ID CIS-596922-FDNS/NSC to include Selection Panel Documents COW2012000566 Estrella, Alejandro 06/07/2012 Inquiry into how many people and their names that requester is financially supporting COW2012000567 Montgomery, David 06/10/2012 All documents submitted by Manassas Ballet Theater and related congressional correspondence COW2012000568 Debrito, Ricardo -

National Coalitions in Israel, 1984-1990

NATIONAL COALITIONS IN ISRAEL, 1984-1990: THE POLITICS OF "NOT LOSING" A Thesis for the degree of Ph.D. Presented to the University of London By Dan Korn London School of Economics May 1992 1 - UMI Number: U549931 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Disscrrlation Publishing UMI U549931 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 o ON CA lA N Abstract For six years since 1984 Israel underwent a unique p o litic al experience: i t was ruled by national coalitions supported by more than 75% of the members of parliament. Larger-than-minimal coalitions have always been problematic for traditional coalition theory. The Israeli case provides therefore an opportunity to examine the various actors' motivations and behaviour, as they reflect on coalition theory at 1arge. The assumption that actors are driven by "win maximization" is central to formal models of coalition theory. This assumption led to predictions of winning coalitions which are minimal in size, membership or ideological scope. Non-minimal coalitions were regarded as suboptimal choices, explainable on an ad hoc basis, e.g. -

ECONOMIC (Ftf^^K ™^ a M H W&Hom B/C1I

UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC (ftf^^k ™^ A M H W&HoM B/C1I. 4/131O AINU' ^S^&W/ 1 February 1979 ^OriAl COllNCH ^r^r-- Original: EHGLISH/EBEHCH/ J \_/ V- I r\U >w^V^MVIL SPA1TISII C0HMIS3I01T OH 1-IUlIft.H EIGHTS Thirty-fifth session Agenda item 5 of the provisional agenda, STUDY OF REPORTED VIOLATIONS OP HUTIA.1T RIGHTS IN CHILE, 1/ITH PARTICULAR REPERE1TCE TO TORTURE AHD n OTHER CRUEL, H iUl;lAH OR DEGRADING TREATlIEFr OR PUHISHMGITT Report.of the Ad Hoc Working Group established under resolution 8 (XXXI) of the Commission on Human Rights to inquire into the situation of human rights in Chile COHTEHTS Paragraphs Page Introduction « 1 - 21 5 Chapter I. • Constitutional and legal developments affecting human rights 22 - 86 13 A. State of siege and state of emergency 22-39 13 B. The specialized State security agencies 40-57 16 C. The role of the judiciary 58 - 6$ 21 D. Civil and political rights; the draft Constitution 70 - 86 24 II. Life, liberty and security of person 87 - 105 30 A, Arrest and detention 88 - 100 30 B, Ill-treatment and torture 101 - 103 36 C, The role of the judiciary in the protection of the right to life, liberty and security of person 104 - 105 39 III. Missing persons 106 - 128 40 IV. Exile and return 129 - 138 47 GE.79-10412 E/CN. 4/1310 page 2 C01M31TTS (contd) Chapter Paragraphs Page V. Freedom of expression and information 139 - 148 50 VI. Right to education 149 - 1^7 54 VII. -

I Costa Do Estada De Foi Varrida, Ficando Quasi Toda Em Ruínas a Ac&Seai&Sacaaasccosaoyxceaaascao

.,..,,. &• '¦!'¦ ''..'_'..',:..-.' ' • "•' ' '¦-'¦'_" '-¦ I Correio da . Manhã: ji'"¦ ."i æ •¦ ,;m1 da Manhl,*' BKCH& — \'DSKNT & C* LTD. — Fornecedores de r"pd para o-"Correio RJ? l-ipress- em papel de HOLMBERG C. Stocltolmo e Riò. Propriedade de EDMUNDO BITTENCOURT <& Cia. Limitada OMM.UN ' DA CARIOCA N. 13 pirecior-PAULO BITTENCOURT .AJ>T:N"0 XXVI —>3Sr. OJ7±4z . LARGO »• im J substituto - M. PAULO . EIOBE JANEIRO— TERÇA-FEIRA, 21 DE SETEMBRO DE 1926 Gerente-V. A. DUARTE FEEI* Director FILHOj ¦'¦*_¦ ¦ . ' *"Í9 ^aaj^m^iammamaammmamammamnmmi—IJ-!." ESPECIAES y '¦" '.' SERVIÇO TELEGRAPHIÇO DA UNITED PRESS, AMERICANA E CORRESPONDENTES •'' im ¦v'-"-f. ^ * S££L.~-«*,'" lempo-| i8. E' Desaba no golpho do Mexícò violento tra a u /•••¦'• ral, coiri terriveis conseqüências ^ariA8 ¦ - ¦¦— ¦ - ¦ Y__-.-WWyW*A*W^^ sooõõõc Tll * 1 I -per- cidade de Miami re I costa do Estada de foi varrida, ficando quasi toda em ruínas a ac&seai&sacaaasccosaoyxceaaascao. Na cidade chineza de Wuchang, onde os nacionalistas estão sitiados, mím me o íypho esíá contribuindo para m sição Liga das Nações O NOVO TRATADO DE AMI- A DIVORCIO à. | ZADE ENTRE A ITÁLIA questão O \\y Uma resolução approvada, EA HESPANHA 1 do Pacifico "Correio da Manti-gi-_f« UNIDOS em favor da realização O ain nas BRANDE CALAMIDADE NOS ESTADOS da Conferência Econômica Estabelece-se nelle a neutra- Continuam detidos em Arica um Inquérito_\g^l-j CXXK>0O00. abre formidável furacão na costa de Florida, causan- •Genebra, 20- (U. P.) — A Liga lidade de um se o outro os tripulantes do avião Desaba adoptou a resolução de das Nações ' respeito 0 <*> do enormes estragos materiaes, centeiiares perdas do representante francez, sr. -

Nuzn 1 9 9 7

ZANU PF ZANU PF LI I U RICA WHAT FUTURE? Zimbabwe News Official Organ of ZANIJ PF Department of lntormarion and Publicity. 144 Union Avenue. H.ar e Tel: 790148 Volume 28, No. 6 1997, Registered art Ihe GPO ts a Newspaper JUNE 1997 $2.50 (incl. sales tax) Zimbabwe News Official Organ of ZANU PF Contents Editorial: Cover Story: National News: Special Reports: Regional File: I write as I like: Address to Central Committe Africa File: International: World Population Special: Sport: Obituaries: OAU: Harare Summit Turning Point ............................................................... 2 Kabila was the star at the Summit ................................................................... 3 Council elections round the comer; tension growing ..................................... 4 O pen U niversity ............................................................................................ 5 Quest for economic prosperity .......................................................................... 8 Environmental policies key to economic growth .......................................... 10 Land still contentious issue ..................................1.... 1 South Africa: Many nations in one .............................................................. 12 Swelling refugee figures a concern ............................................................... 15 Focus on decisions of the OAU Summit ....................................................... 16 Let us defend and invigorate the Party ......................................................... -

Los Orígenes De La Teología De La Liberación En

ISSN 0120-131X • 2389-9980 (en línea) | Vol. 43 | No. 99 | Enero-junio • 2016 | pp. 73-108 Cuestiones Teológicas | Medellín-Colombia http://dx.doi.org/10.18566/cueteo.v43n99.a04 LOS ORÍGENES DE LA TEOLOGÍA DE LA LIBERACIÓN EN COLOMBIA: RICHARD SHAULL, CAMILO TORRES, RAFAEL ÁVILA, “GOLCONDA”, SACERDOTES PARA AMÉRICA LATINA, CRISTIANOS POR EL SOCIALISMO Y COMUNIDADES ECLESIALES DE BASE1 Origins of Liberation Theology in Colombia: Richard Shaull, Camilo Torres, Rafael Ávila, “Golconda”, Priests for Latin America, Christians for Socialism and Basic Ecclesial Communities Os primórdios da teologia da libertação na Colômbia: Richard Shaull, Camilo Torres, Rafael Ávila, “golconda”, sacerdotes para América Latina, cristãos pelo socialismo e comunidades eclesiais de base Victorino Pérez Prieto PhD2 1 Este trabajo es un producto del Proyecto de Investigación “Diálogo interreligioso, liberación y paz en Colombia” del autor, Grupo Devenir, Línea de investigación: Ética y antropología filosófica, Universidad de San Buenaventura-Bogotá. El proyecto está programado para realizarse en los años 2015-2016. 2 Victorino Pérez Prieto, CE 515092. Doctor en Teología por la Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca (UPSA), Doctor en Filosofía por la Universidad de Santiago de Compostela (USC), con un Master de esa Universidad en “Cuestiones actuales de Filosofía”. Atribución – Sin Derivar – No comercial: El material creado por usted puede ser distribuido, copiado y exhibido por terceros si se muestra en los créditos. No se puede obtener ningún beneficio comercial. No se pueden realizar obras derivadas | 73 Victorino Pérez Prieto Resumen El presente trabajo parte del presupuesto -justificado en el primer apartado- de que la Teología de la Liberación (TdeL) no solamente es la más original que se ha elaborado en los más de cuatrocientos años de teología en América Latina, sino la primera teología cristiana propiamente latinoamericana, fiel al grito profético de los primeros misioneros cristianos, en defensa de los oprimidos. -

Memoria Cccb 2014 En.Pdf

CCCB Annual Report 2014 CCCB Annual Report 2014 CCCB Annual Report 2014 Montalegre, 5 08001 Barcelona T. 933 064 100 www.cccb.org @cececebe www.facebook.com/CCCB.Barcelona www.instagram.com/el_cccb/ A consortium of Contents 20 Years of the CCCB 08 Espriu. I Looked upon this Land 12 Exhibitions 10 Metamorphosis. Fantasy Visions in Starewitch, 13 Švankmajer and the Quay Brothers The Start of Tomorrow. 14 Mancomunitat of Catalonia: 100 years Shared Cities. 15 European Prize for Urban Public Space 2014 Big Bang Data 16 Under Siege. Mariam Ghani and Omer Fast. 17 Installation and conversations World Press Photo. International Professional 18 Photojournalism Exhibition Arissa. The Shadow and the Photographer, 1922-1936 19 Shadowland by Kazuhiro Goshima 20 Festivals and Open Formats 24 Festivals 22 Children’s and Family Programme 42 and Open Formats Debates and Lectures 46 Spaces for Debate 44 In Collaboration 57 and Reflection Courses, Postgraduate Certificates 61 and Master’s degrees European Prize 64 for Urban Public Space CCCB Lab 70 CCCB Lab 68 Networked Projects 75 Friends 76 of the CCCB CCCB Education 80 Social Programme 88 Exhibitions 94 Beyond the CCCB 92 European Prize for Urban Public Space 98 Archives 102 CCCB Holdings 100 Archives in Collaboration 103 Publications 104 Collaborating Institutions and Companies 108 General Details 106 Speakers at Debates and Lectures 110 Use and Rental of Spaces 112 Visiting Figures and Audience 114 Budget 118 CCCB Staff 119 Selection from the Press 120 8 20 Years of the CCCB The year 2014 marked the 20th Anniversary of the CCCB. Over the course of its first 20 years, the Centre has substantially increased its range of activity and its outreach.