Framing Memory: the Bombings of Dresden, Germany in Narrative, Discourse and Commemoration After 1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dresden Kempinski

World Travel Professionals Level 22 333 Ann Street Brisbane QLD 4000 T +61 7 3220 2277 F +61 7 3220 2288 E [email protected] W www.worldtravel.com.au Australian Bar Association Conference DRESDEN 27 – 29 June 2011 CONFERENCE HOTEL Hotel Taschenbergpalais Kempinski Taschenberg 3 D 01067 DRESDEN GERMANY Phone: 49 351 4912 612 Fax: 49 351 4912 646 www.kempinski-dresden.de Hotel Location The Taschenbergpalais Kempinski is located in the city centre of Dresden and is only a few steps away from renowned sights of Semper Opera House, the Residential Castle, Zwinger and Frauenkirche. Hotel Features The hotel has 214 rooms including 32 suites, on 4 levels, both Smoking and Nonsmoking. There are several Restaurants, including Restaurant Intermezzo, the Palais Bistro, or Café Vestibül Check in Time: 3pm Checkout Time: 12 Noon Room Features Kurfürsten Deluxe Rooms 45 m with - Views to the baroque scenery of Dresden - Lounge area with armchairs - Writing Desk and chair - Pillow Options - Individually adjustable Air-Conditioning - Separate Bathtub, Shower and separate Toilet - Internet Protocol Television with 100 Channels - High Speed Internet and Wireless LAN at EUR25 per day - ISDN Telephone including cordless Telephone for in-house use and fax connection - 110 V Plugs- American Standard – for small Appliances - Hairdryer World Travel Professionals ABN 92 080 629 689 Lic No. TAG 1502 World Travel Professionals Level 22 333 Ann Street Brisbane QLD 4000 T +61 7 3220 2277 F +61 7 3220 2288 E [email protected] W www.worldtravel.com.au Page 2 - Window can be opened - Safe - Laundry/Ironing Facilities - 24 hour Room Service - Bath Robes - Daily Newspaper Business Centre Full Service ABA Room Allotment from 27 June to 30 June 2011 Pre and Post Allotment Nights at Conference Rate upon Request. -

USSBS Kyushu Airplane Co., Report No. XV.Pdf

^ ^.^41LAU Given By U. S. SlIPT. OF DOCUMENTS 3^ THE UNITED STATES STRATEGIC BOMBING SURVEY Kyushu Airplane Company CORPORATION REPORT NO. XV (Airframes) uV Aircraft Division February 1947 \b THE UNITED STATES STRATEGIC BOMBING SURVEY Kyushu Airplane Company (Kyushu Hikoki K K) CORPORATION REPORT NO. XV (Airframes) Aircraft Division Dates of Survey: 13-15 November 1945 Date of Publication: February 1947 \A/, -, APfi 8 ,947 This report was written primarily for the use of the United States Stra- tegic Bombing Survey in the preparation of further reports of a more comprehensive nature. Any conclusions or opinions expressed in this report must be considered as limited to the specific material covered and as subject to further interpretation in the light of further studies conducted by the Survey. FOREWORD The United States Strategic Bombing Survey was establislied by the Secretary of War on 3 November 1944, pursuant to a directive from the late President Roosevelt. Its mission was to conduct an impartial and expert study of the effects of our aerial attack on Germany, to be used in connection with air attacks on Japan and to establish a basis for evaluating the importance and potentialities of air power as an instrument of military strategy for planning the future development of the United States armed forces and for determining future economic policies with respect to the national defense. A summary report and some 200 support- ing reports containing the findings of the Survey in Germany have been published. On 15 August 1945, President Truman requested that the Survey conduct a similar study of the effects of all types of air attack in the war against Japan, submitting reports in duplicate to the Secretary of War and to the Secretary of the Navy. -

The Theatricality of the Baroque City: M

THE THEATRICALITY OF THE BAROQUE CITY: M. D. PÖPPELMANN’S ZWINGER AT DRESDEN FOR AUGUSTUS THE STRONG OF SAXONNY PATRICK LYNCH TRINITY HALL CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY 1996 MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION THE HISTORY AND PHILSOPHY OF ARCHITECTURE 1 CONTENTS: Acknowledgements. Preface. 1 Introduction to the topic of theatricality as an aspect of the baroque. i.i The problem of the term baroque. i.ii The problem of theatricality in the histories of baroque architecture: i.ii.a The theatricality of the Frame. i.ii.b The theatricality of Festival. ii The hermeneutics of theatricality: ii.i Hans-Georg Gadamer's formulation of play, symbol and festival as an interpretation of baroque theatricality. 2 The historical situation of the development of the Zwinger. i The European context. ii The local context. 3 The urban situation of the Zwinger. i Barockstadt Dresden. ii Barockstaat Sachsen. 4 A description of the development of the Zwinger. Conclusion: i Festival and the baroque city. A description of the Zwinger in use as it was inaugurated during the wedding celebrations of Augustus III and Marie Josepha von Habsburg, September 1719. ii Theatricality and the city. Bibliography. Illustrations: Volume 2 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: I would like to thank D.V. for supervising me in his inimitable way, and Dr. Christopher Padfield (and Trinity Hall) for generous financial support. This dissertation is dedicated to my family and friends, absent or otherwise and to C.M. in particular for first showing me the Zwinger and without whose care this document would not exist. PATRICK LYNCH 09/96 3 'Als ich nach der Augustusbrücke kam, die ich schon so gut aus Kupferstichen und Gemälden kannte, kam es mir vor, als ob ich schon früher einmal in Traum hier gewesen wäre.' (As I came upon the Augustusbrücke, which I knew so well from engravings and paintings, it seemed to me as if I had been here once before, in a dream.) Hans Christian Andersen 'This luscious and impeccable fruit of life Falls, it appears, of its own weight to earth. -

2363 Luftaufnahme Des KZ Dachau, 20. April 1945 Aerial View of The

54 53 28 52 67 63 66 65 31 51 58 60 80 28 30 48 50 58 59 64 58 49 58 62 58 29 58 60 47 70 27 57 61 28 57 41 45 55 72 44 21 56 40 71 26 43 42 46 20 79 45 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 1 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 78 9 10 17 25 3 7 8 4 2 6 7 11 16 12 13 28 14 15 25 27 29 5 1 3 579 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 73 74 75 77 76 2363 Luftaufnahme des KZ Dachau, 20. April 1945 Luftbilddatenbank Ing. Büro Dr. Carls, Würzburg Aerial view of the Dachau concentration camp, April 20, 1945 Gebäude und Einrichtungen Buildings and facilities of the des KZ Dachau, 1945 Dachau concentration camp, 1945 Außenmauer/-zaun des KZ Krematoriumsbereich Exterior wall/fence of the Medicinal herb garden “plantation” concentration camp Umzäunung des Häftlingslagers mit Wachtürmen Heilkräutergarten „Plantage“ Fence of the Prisoners‘ camp Crematorium area with guard towers 1 Jourhaus mit Lagereingang 43 Werkstätten der Deutschen 1 Jourhaus with camp entrance 44 Commandants headquarters of the 2 Appellplatz Ausrüstungs-Werke (DAW) 2 Roll-call square concentration camp 3 Wirtschaftsgebäude 44 Kommandantur des Konzentrations- 3 Maintenance building 45 Political department (Gestapo) 4 Bunker lagers 4 Bunker (camp prison) 46 Barracks of the concentration camp 5 Straflager der Waffen-SS und Polizei 45 Politische Abteilung (Gestapo) 5 Penal camp of the Waffen SS and Police guards 6 Lagerstraße 46 Baracken-Unterkünfte der 6 The camp road 47 Paymaster offices of the Waffen SS 7 Baracken (Materiallager) KZ-Wachmannschaften 7 Barracks (lay down) 48 SS living quarter and administration 8 Lagermuseum, -

Soundscapes of Air Warfare in Second World War Britain

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery Moaning Minnie and the Doodlebugs: Soundscapes of Air Warfare in Second World War Britain Gabriel Moshenska Familiar sounds were no longer heard; church bells were silenced; they were only to be as a warning of invasion. Whistles, tube type used by the police as well as the rattling pea type, were to warn of gas attack, while hand bells and football ricketys were only to be used as an indicator of some kind of alarm which escapes me now. Works horns, used to indicate starting, lunch breaks, and stopping times, steam operated like those fitted to ships’ funnels, were briefly silenced but were soon brought back into use to maintain production. (Rountree 2004) Introduction: First broadcast in 1968, the BBC television sitcom Dad’s Army depicted the comic antics of the Walmington-on-Sea Home Guard, and remains an icon of British comedy. As the theme tune fades in the closing credits of the show an air raid siren sounds the ‘All Clear’, the tone that signaled the end of an air raid or alert period in British towns and cities during the Second World War. For many of those watching Dad’s Army the sound would have been deeply and possibly painfully familiar, triggering memories of wartime: one man, a child during the war, recalled almost sixty years afterwards “How welcome was Minnie's steady 'all clear' note when the raids were over. Whenever that note sounds at the end of an episode of 'Dad's Army' it still brings a lump to my throat and reminds me of those difficult times” (Beckett 2003). -

Meissen Masterpieces Exquisite and Rare Porcelain Models from the Royal House of Saxony to Be Offered at Christie’S London

For Immediate Release 30 October 2006 Contact: Christina Freyberg +44 20 7 752 3120 [email protected] Alexandra Kindermann +44 20 7 389 2289 [email protected] MEISSEN MASTERPIECES EXQUISITE AND RARE PORCELAIN MODELS FROM THE ROYAL HOUSE OF SAXONY TO BE OFFERED AT CHRISTIE’S LONDON British and Continental Ceramics Christie’s King Street Monday, 18 December 2006 London – A collection of four 18th century Meissen porcelain masterpieces are to be offered for sale in London on 18 December 2006 in the British and Continental Ceramics sale. This outstanding Meissen collection includes two white porcelain models of a lion and lioness (estimate: £3,000,000-5,000,000) and a white model of a fox and hen (estimate: £200,000-300,000) commissioned for the Japanese Palace in Dresden together with a white element vase in the form of a ewer (£10,000-15,000). “The porcelain menagerie was an ambitious and unparalleled project in the history of ceramics and the magnificent size of these models is a testament to the skill of the Meissen factory,” said Rodney Woolley, Director and Head of European Ceramics. “The sheer exuberance of these examples bears witness to the outstanding modelling of Kirchner and Kändler. The opportunity to acquire these Meissen masterpieces from the direct descendants of Augustus the Strong is unique and we are thrilled to have been entrusted with their sale,” he continued. The works of art have been recently restituted to the heirs of the Royal House of Saxony, the Wettin family. Commenting on the Meissen masterpieces, a spokesperson for the Royal House of Saxony said: “The Wettin family has worked closely, and over many years with the authorities to achieve a successful outcome of the restitution of many works of art among which are these four Meissen porcelain objects, commissioned by our forebear Augustus the Strong. -

The Belfast Blitz

The Belfast Blitz Blitz is short for ‘Blitzkrieg’ which is the German word for a lightning war. It was named after the bombs, light flashes and the noise of the German bomber planes in the Second World War. Belfast was one of the most bombed cities in the UK. The worst attacks were on 15th April 1941 and 4th May 1941. Unprepared James Craig (Lord Craigavon) was prime minister of Northern Ireland and was responsible for preparing Belfast for any attacks by the German ‘Luftwaffe’. He and his team did very little to prepare the city for the bombings. In fact, they even forgot to tell the army that an attack might happen! Belfast was completely unprepared for the Blitz. Belfast had a large number of people living in the city but it had very few air raid shelters. There were only 200 public shelters in the whole of Belfast for everyone to share. Searchlights were designed to scan the sky for bombing aircrafts. However, they were not even set up before the attacks began. The Germans were much better prepared. They knew Belfast was not ready for them. They choose seven targets to hit: Belfast Power Station, Belfast Waterworks, Connswater Gasworks, Harland and Wolff Shipyards, Rank and Co. Mill, Short’s Aircraft Factory and Victoria Barracks. Why Was Belfast Attacked? Belfast was famous and still is famous for ship building and aircraft building. At the time of the Blitz, the Harland and Wolff shipyards were some of the largest in the world. There were over 3,000 ships in the Belfast docks area and the Germans wanted to destroy them. -

Lord Healey CH MBE PC

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 31 (Incorporating the Proceedings of the Bomber Command Association’s 60th Anniversary Symposium) 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Photographs credited to MAP have been reproduced by kind permission of Military Aircraft Photographs. Copies of these, and of many others, may be obtained via http://www.mar.co.uk First published in the UK in 2004 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Typeset by Creative Associates 115 Magdalen Road Oxford OX4 1RS Printed by Advance Book Printing Unit 9 Northmoor Park Church Road Northmoor OX29 5UH 3 CONTENTS RECOLLECTIONS OF A SECRETARY OF STATE FOR 4 DEFENCE – The Rt Hon The Lord Healey CH MBE PC HOW DECISIVE WAS THE ROLE OF ALLIED AIR POWER 17 IN THE WAR IN THE PACIFIC, 1941-1945? by Sqn Ldr S I Richards SUMMARY OF THE MINUTES OF THE SEVENTEENTH 47 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING HELD IN THE ROYAL AIR FORCE CLUB ON 10 JUNE 2003 FEEDBACK 51 DEREK WOOD – AN OBITUARY 55 BOOK REVIEWS 56 PROCEEDINGS OF THE BOMBER COMMAND 82 ASSOCIATION 60TH ANNIVERSARY SYMPOSIUM HELD AT THE RAF MUSEUM, HENDON ON 12 OCTOBER 2002 UNDER THE CHAIRMANSHIP OF AIR MSHL SIR JOHN CURTISS KCB KBE 4 RECOLLECTIONS OF A SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE The Rt Hon The Lord Healey CH MBE PC I should perhaps start by saying that there is no specific theme to what I have to say. -

Commentaries

Santander Art and Culture Law Review 2/2015 (1): 245-258 DOI: 10.4467/2450050XSR.15.021.4519 COMMENTARIES Uwe Scheffler* Dela-Madeleine Halecker** [email protected] [email protected] Robert Franke*** Lisa Weyhrich**** [email protected] [email protected] European University Viadrina Frankfurt (Oder) Große Scharrnstraße 59 D-15230 Frankfurt (Oder), Germany When Art Meets Criminal Law – Examining the Evidence1 * Prof. Dr. Dr. Uwe Scheffler is since 1993 holder of the Chair of Criminal Law, Law of Criminal Procedure and Criminology at the European University Viadrina in Frankfurt (Oder). His main research interests are criminal law reform, criminal traffic law, medical ethics and criminality in the border area. ** Dr. Dela-Madeleine Halecker studied law at the European University Viadrina in Frankfurt (Oder), where she gained a doctorate in 2008 with a study on the traffic ban. She is research assistant at the Chair of Criminal Law, Law of Criminal Procedure and Criminology of the European University Viadrina in Frank- furt (Oder). *** Dipl.-Jur. Robert Franke, LL.M., studied law at the European University Viadrina in Frankfurt (Oder), where he served as an assistant in the research project “Art and Criminal Law”. **** Stud. iur. Lisa Weyhrich is a student assistant at the Chair of Criminal Law, Law of Criminal Proce- dure and Criminology of the European University Viadrina in Frankfurt (Oder). 1 The team of the Chair of Criminal Law, Law of Criminal Procedure and Criminology of the European University Viadrina in Frankfurt (Oder) organised an exhibition entitled “Art and Criminal Law” in the Main Building of the University in the 2013/2014 winter semester. -

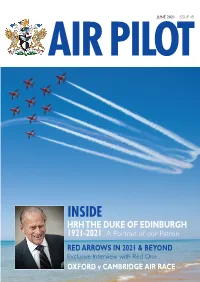

June 2021 Issue 45 Ai Rpi Lo T

JUNE 2021 ISSUE 45 AI RPI LO T INSIDE HRHTHE DUKE OF EDINBURGH 1921-2021 A Portrait of our Patron RED ARROWS IN 2021 & BEYOND Exclusive Interview with Red One OXFORD v CAMBRIDGE AIR RACE DIARY With the gradual relaxing of lockdown restrictions the Company is hopeful that the followingevents will be able to take place ‘in person’ as opposed to ‘virtually’. These are obviously subject to any subsequent change THE HONOURABLE COMPANY in regulations and members are advised to check OF AIR PILOTS before making travel plans. incorporating Air Navigators JUNE 2021 FORMER PATRON: 26 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Duxford His Royal Highness 30 th T&A Committee Air Pilot House (APH) The Prince Philip Duke of Edinburgh KG KT JULY 2021 7th ACEC APH GRAND MASTER: 11 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Henstridge His Royal Highness th The Prince Andrew 13 APBF APH th Duke of York KG GCVO 13 Summer Supper Girdlers’ Hall 15 th GP&F APH th MASTER: 15 Court Cutlers’ Hall Sqn Ldr Nick Goodwyn MA Dip Psych CFS RAF (ret) 21 st APT/AST APH 22 nd Livery Dinner Carpenters’ Hall CLERK: 25 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Weybourne Paul J Tacon BA FCIS AUGUST 2021 Incorporated by Royal Charter. 3rd Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Lee on the Solent A Livery Company of the City of London. 10 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Popham PUBLISHED BY: 15 th Air Pilot Flying Club The Honourable Company of Air Pilots, Summer BBQ White Waltham Air Pilots House, 52A Borough High Street, London SE1 1XN SEPTEMBER 2021 EMAIL : [email protected] 15 th APPL APH www.airpilots.org 15 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Oaksey Park th EDITOR: 16 GP&F APH Allan Winn EMAIL: [email protected] 16 th Court Cutlers’ Hall 21 st Luncheon Club RAF Club DEPUTY EDITOR: 21 st Tymms Lecture RAF Club Stephen Bridgewater EMAIL: [email protected] 30 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Compton Abbas SUB EDITOR: Charlotte Bailey Applications forVisits and Events EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTIONS: The copy deadline for the August 2021 edition of Air Pilot Please kindly note that we are ceasing publication of is 1 st July 2021. -

Civil Defense and Chemical Warfare in Great Britain, 1915-1945 Jordan I

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-7-2018 Britain Can Take It: Civil Defense and Chemical Warfare in Great Britain, 1915-1945 Jordan I. Malfoy [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC006585 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Military History Commons, Political History Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Malfoy, Jordan I., "Britain Can Take It: Civil Defense and Chemical Warfare in Great Britain, 1915-1945" (2018). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3639. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3639 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida BRITAIN CAN TAKE IT: CHEMICAL WARFARE AND THE ORIGINS OF CIVIL DEFENSE IN GREAT BRITAIN, 1915 - 1945 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY by Jordan Malfoy 2018 To: Dean John F. Stack, Jr. choose the name of dean of your college/school Green School of International and Public Affairs choose the name of your college/school This disserta tion, writte n by Jordan Malfoy, and entitled Britain Can Take It: Chemical Warfare and the Ori gins of Civil D efense i n Great Britain, 1915-1945, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. -

The First Americans the 1941 US Codebreaking Mission to Bletchley Park

United States Cryptologic History The First Americans The 1941 US Codebreaking Mission to Bletchley Park Special series | Volume 12 | 2016 Center for Cryptologic History David J. Sherman is Associate Director for Policy and Records at the National Security Agency. A graduate of Duke University, he holds a doctorate in Slavic Studies from Cornell University, where he taught for three years. He also is a graduate of the CAPSTONE General/Flag Officer Course at the National Defense University, the Intelligence Community Senior Leadership Program, and the Alexander S. Pushkin Institute of the Russian Language in Moscow. He has served as Associate Dean for Academic Programs at the National War College and while there taught courses on strategy, inter- national relations, and intelligence. Among his other government assignments include ones as NSA’s representative to the Office of the Secretary of Defense, as Director for Intelligence Programs at the National Security Council, and on the staff of the National Economic Council. This publication presents a historical perspective for informational and educational purposes, is the result of independent research, and does not necessarily reflect a position of NSA/CSS or any other US government entity. This publication is distributed free by the National Security Agency. If you would like additional copies, please email [email protected] or write to: Center for Cryptologic History National Security Agency 9800 Savage Road, Suite 6886 Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755 Cover: (Top) Navy Department building, with Washington Monument in center distance, 1918 or 1919; (bottom) Bletchley Park mansion, headquarters of UK codebreaking, 1939 UNITED STATES CRYPTOLOGIC HISTORY The First Americans The 1941 US Codebreaking Mission to Bletchley Park David Sherman National Security Agency Center for Cryptologic History 2016 Second Printing Contents Foreword ................................................................................