Defence Forces Review 2020 Defence Forces Review 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Conditions for Danish Defence Policy – Strategic Choices

centre for military studies university of copenhagen An Analysis of Conditions for Danish Defence Policy – Strategic Choices 2012 This analysis is part of the research-based services for public authorities carried out at the Centre for Military Studies for the parties to the Danish Defence Agreement. Its purpose is to analyse the conditions for Danish security policy in order to provide an objective background for a concrete discussion of current security and defence policy problems and for the long-term development of security and defence policy. The Centre for Military Studies is a research centre at the Department of —Political Science at the University of Copenhagen. At the centre research is done in the fields of security and defence policy and military strategy, and the research done at the centre forms the foundation for research-based services for public authorities for the Danish Ministry of Defence and the parties to the Danish Defence Agreement. This analysis is based on research-related method and its conclusions can —therefore not be interpreted as an expression of the attitude of the Danish Government, of the Danish Armed Forces or of any other authorities. Please find more information about the centre and its activities at: http://cms.polsci.ku.dk/. References to the literature and other material used in the analysis can be found at http://cms.polsci.ku.dk/. The original version of this analysis was published in Danish in April 2012. This version was translated to English by The project group: Major Esben Salling Larsen, Military Analyst Major Flemming Pradhan-Blach, MA, Military Analyst Professor Mikkel Vedby Rasmussen (Project Leader) Dr Lars Bangert Struwe, Researcher With contributions from: Dr Henrik Ø. -

NUI MAYNOOTH MILITARY AVIATION in IRELAND 1921- 1945 By

L.O. 4-1 ^4- NUI MAYNOOTH QllftMll II hiJfiifin Ui Mu*« MILITARY AVIATION IN IRELAND 1921- 1945 By MICHAEL O’MALLEY THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH Supervisor of Research: Dr. Ian Speller JANUARY 2007 IRISH MILITARY AVIATION 1921 - 1945 This thesis initially sets out to examine the context of the purchase of two aircraft, on the authority of Michael Collins and funded by the second Dail, during the Treaty negotiations of 1921. The subsequent development of civil aviation policy including the regulation of civil aviation, the management of a civil aerodrome and the possible start of a state sponsored civil air service to Britain or elsewhere is also explained. Michael Collins’ leading role in the establishment of a small Military Air Service in 1922 and the role of that service in the early weeks of the Civil War are examined in detail. The modest expansion in the resources and role of the Air Service following Collins’ death is examined in the context of antipathy toward the ex-RAF pilots and the general indifference of the new Army leadership to military aviation. The survival of military aviation - the Army Air Corps - will be examined in the context of the parsimony of Finance, and the administrative traumas of demobilisation, the Anny mutiny and reorganisation processes of 1923/24. The manner in which the Army leadership exercised command over, and directed aviation policy and professional standards affecting career pilots is examined in the contexts of the contrasting preparations for war of the Army and the Government. -

Vs - Nur Für Den Dienstgebrauch

VS - NUR FÜR DEN DIENSTGEBRAUCH NATO UNCLASSIFIED NATO UNCLASSIFIED Foreword The term “counterinsurgency” (COIN) is an The document is divided into three parts: emotive subject in Germany. It is generally • Part A provides the basic conceptual accepted within military circles that COIN is an framework as needed to give a better interagency, long-term strategy to stabilise a crises understanding of the broader context. It region. In this context fighting against insurgents specifically describes the overall interagency is just a small part of the holistic approach of approach to COIN. COIN. Being aware that COIN can not be achieved successfully by military means alone, it • Part B shifts the focus to the military is a fundamental requirement to find a common component of the overall task described sense and a common use of terms with all civil previously. actors involved. • Part C contains some guiding principles to However, having acknowledged an Insurgency to stimulate discussions as well as a list of be a group or movement or as an irregular activity, abbreviations and important reference conducted by insurgents, most civil actors tend to documents. associate the term counterinsurgency with the combat operations against those groups. As a The key messages of the “Preliminary Basics for the Role of the Land Forces in COIN“ are: result they do not see themselves as being involved in this fight. For that, espescially in • An insurgency can not be countered by Germany, the term COIN has been the subject of military means alone. much controversy. • Establishing security and state order is a long- Germany has resolved this challenge with two term, interagency and usually multinational steps. -

Stability and Arms Control in Europe: the Role of Military Forces Within a European Security System

Stability and Arms Control in Europe: The Role of Military Forces within a European Security System A SIPRI Research Report Edited by Dr Gerhard Wachter, Lt-General (Rtd) and Dr Axel Krohn sipri Stockholm International Peace Research Institute July 1989 Copyright © 1989 SIPRI All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN 91-85114-50-2 Typeset and originated by Stockholm International Peace Research Institute Printed and bound in Sweden by Ingeniörskopia Solna Abstract Wachter, G. and Krohn, A., eds, Stability and Arms Control in Europe: The Role of Military Forces within a European Security System, A SIPRI Research Report (SIPRI: Solna, Sweden, 1989), 113 pp. This report presents the outcome of a project which was initiated at SIPRI in 1987. It was supported by a grant from the Volkswagen Stiftung of the Federal Republic of Germany. The introductory chapter by the editors presents a scenario for a possible future European security system. Six essays by active NATO and WTO military officers focus on the role of military forces in such a system. Various approaches to the tasks and size of military forces in this regime of strict non-provocative defence are presented with the intent of providing new ideas for the debate on restructuring of forces in Europe. There are 3 maps, 7 tables and 11 figures. Sponsored by the Volkswagen Stiftung. Contents Preface vi Acknowledgements viii The role of military forces within a European security system 1 G. -

Irish Political Review, January, 2011

Of Morality & Corruption Ireland & Israel Another PD Budget! Brendan Clifford Philip O'Connor Labour Comment page 16 page 23 back page IRISH POLITICAL REVIEW January 2011 Vol.26, No.1 ISSN 0790-7672 and Northern Star incorporating Workers' Weekly Vol.25 No.1 ISSN 954-5891 Economic Mindgames Irish Budget 2011 To Default or Not to Default? that is the question facing the Irish democracy at present. In normal circumstances this would be Should Ireland become the first Euro-zone country to renege on its debts? The bank debt considered an awful budget. But the cir- in question has largely been incurred by private institutions of the capitalist system, cumstances are not normal. Our current which. made plenty money for themselves when times were good—which adds a budget deficit has ballooned to 11.6% of piquancy to the choice ahead. GDP (Gross Domestic Product) excluding As Irish Congress of Trade Unions General Secretary David Begg has pointed out, the bank debt (over 30% when the once-off Banks have been reckless. The net foreign debt of the Irish banking sector was 10% of bank recapitalisation is taken into account). Gross Domestic Product in 2003. By 2008 it had risen to 60%. And he adds: "They lied Our State debt to GDP is set to increase to about their exposure" (Irish Times, 13.12.10). just over 100% in the coming years. A few When the world financial crisis sapped investor confidence, and cut off the supply of years ago our State debt was one of the funds to banks across the world, the Irish banks threatened to become insolvent as private lowest, but now it is one of the highest, institutions. -

Reconciling Ireland's Bail Laws with Traditional Irish Constitutional Values

Reconciling Ireland's Bail Laws with Traditional Irish Constitutional Values Kate Doran Thesis Offered for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Law Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences University of Limerick Supervisor: Prof. Paul McCutcheon Submitted to the University of Limerick, November 2014 Abstract Title: Reconciling Ireland’s Bail Laws with Traditional Irish Constitutional Values Author: Kate Doran Bail is a device which provides for the pre-trial release of a criminal defendant after security has been taken for the defendant’s future appearance at trial. Ireland has traditionally adopted a liberal approach to bail. For example, in The People (Attorney General) v O’Callaghan (1966), the Supreme Court declared that the sole purpose of bail was to secure the attendance of the accused at trial and that the refusal of bail on preventative detention grounds amounted to a denial of the presumption of innocence. Accordingly, it would be unconstitutional to deny bail to an accused person as a means of preventing him from committing further offences while awaiting trial. This purist approach to the right to bail came under severe pressure in the mid-1990s from police, prosecutorial and political forces which, in turn, was a response to a media generated panic over the perceived increase over the threat posed by organised crime and an associated growth in ‘bail banditry’. A constitutional amendment effectively neutralising the effects of the O'Callaghan jurisprudence was adopted in 1996. This was swiftly followed by the Bail Act 1997 which introduced the concept of preventative detention (in the bail context) into Irish law. -

Historical Skin of Peter "Hoagy" Carmichael's Hawker Sea Fury, the Legendary One That Shot Down a Mig-15 Over Korea

1 [REGISTER] [ACE OF THE MONTH] Lt JG Tetsuzo Iwamoto………………………………………………………. 2 #A6M2 Mod 21, Petty Officer First Class Tetsuzo Iwamoto, Zuikaku Carrier Air Group, Pearl Harbor Attack, 7th December 1941. Camouflage created by max_86z [AIR FORCES] Israeli Air Force………………………………………………………………………………. 6 'P-51D-5 of the Israeli Air Force, 1956' skin by _TerremotO_ [EVENT] Landing in Normandy……………………………………………………………………………. 10 D-Day wallpaper [VEHICLE PROFILE] TBF-1c / Avenger Mk 1………………………………………………………….. 12 A TBF-1C of the VC-8. Camouflage with custom damage textures created by Hueynam1234 [VEHICLE PROFILE] M46 Patton…………………………………………………………………………… 16 M46 Patton 64th Tank Bat. [Han River 1951] camouflage created by Tiger_VI [EVENT] Battles over Malta………………………………………………………………………………… 19 Malta Siege wallpaper [NATIONAL FORCES] 653rd Heavy Panzerjäger Battalion……………………………………. 21 Jagdtiger 653rd Heavy Panzerjäger Battalion *Germany 1945+, camouflage created by Tiger_VI [AIR FORCES] Mexican Expeditionary Air Forces…………………………………………………. 24 P-47 wallpaper in Mexican Air Forces camouflage; Republic P-47D-28 from Escuadrón 201, camouflage created by RiderR2 [VEHICLE PROFILE] Hawker Sea Fury……………………………………………………….. 27 Sea Fury wallpaper; Historical skin of Peter "Hoagy" Carmichael's Hawker Sea Fury, the legendary one that shot down a MiG-15 over Korea. Camouflage created by printf8via [HISTORICAL] Guns of the Air, the RCMs and HMGs………………………………… 31 [VEHICLE PROFILE] PzKpfw KV-1B 756(r)…………………………………………………. 35 KV-1B wallpaper [NATIONAL FORCES] The Irish Air Corps……………………………………………………………… 39 No.1 Fighter Squadron, Irish Army Air Corps at Baldonnel, Ireland, by CmdNomad [EVENT] Blue on Blue…………………………………………………………………………………………. 42 US light tanks wallpaper 1 #A6M2 Mod 21, Petty Officer First Class Tetsuzo Iwamoto, Zuikaku Carrier Air Group, Pearl Harbor Attack, 7th December 1941. Camouflage created by max_86z [ACE OF THE MONTH] Lt JG Tetsuzo Iwamoto 1. -

Murphy TD Representing You in Dáil Éireann

EOGHAN MURPHY TD Representing You in Dáil Éireann NEWSLEttER 04, 2012 Investigating Public Accounts The Public Accounts Committee recently published two reports: on the Irish Red Cross, and on VAT costs on the National Aquatic Centre. These are important documents produced by the one committee in Dail Eireann that is empowered to investigate public spending and whether or not value for money is being achieved for the taxpayer. On the PAC, I have also taken the lead investigating activities in NAMA, the €3.6bn accounting error in Finance and the Poolbeg Incinerator. I am also a member of the sub- committee for the coming Banking Enquiry, which will release its first report soon. Eoghan questioning officials from NAMA at the Public Accounts Committee DublinBikes, but with Cars! Improving how we get around the city has been one of my priorities since the election. I was the first government member to introduce a private members bill: The Smarter REAREADD INSIINSIDED E ➤ ➤ ➤ ➤ ➤ ➤ ➤ Transport Bill 2011. This Bill will give power to local authorities to introduce electric cars and car sharing car Page clubs to our city streets. Car clubs are like Dublinbikes, ❶ DublinBikes, but with cars but with cars. This should make car use cheaper and ❶ Investigating Public Accounts easier for individuals, while also having a positive impact on the local environment. It is hoped the new laws will ❷ Entrepreneurs making moves in Dublin come in to effect in the first quarter of 2013. ❸ Bringing transparency to how we spend your money ❸ Smarter communications ❸ Local reports ❹ Report a Problem ❹ Raise a National Issue EOGHAN MURPHY TD - Working for you Entrepreneurs Making Moves in Dublin ● In March we saw the Irish University Entrepreneurs Forum officially launch with an event to connect business leaders and investors with entrepreneurs in third level institutions. -

Dáil Éireann

Vol. 1006 Wednesday, No. 7 12 May 2021 DÍOSPÓIREACHTAÍ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DÁIL ÉIREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIÚIL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) Insert Date Here 12/05/2021A00100Ábhair Shaincheisteanna Tráthúla - Topical Issue Matters 884 12/05/2021A00175Saincheisteanna Tráthúla - Topical Issue Debate 885 12/05/2021A00200Digital Hubs ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������885 12/05/2021B00350Hospital Waiting Lists 887 12/05/2021C00400Special Educational Needs 891 12/05/2021E00300Harbours and Piers 894 12/05/2021F00600Companies (Protection of Employees’ Rights in Liquidations) Bill 2021: Second Stage [Private Members] 897 12/05/2021S00500Ceisteanna ó Cheannairí - Leaders’ Questions 925 12/05/2021W00500Ceisteanna ar Reachtaíocht a Gealladh - Questions on Promised Legislation 935 12/05/2021AA00800Pensions (Amendment) (Transparency in Charges) Bill 2021: First Stage 945 12/05/2021AA01700Health (Regulation of Termination of Pregnancy) (Foetal Pain Relief) Bill 2021: First Stage 946 12/05/2021BB00900Ministerial Rota for Parliamentary Questions: Motion -

Lord Healey CH MBE PC

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 31 (Incorporating the Proceedings of the Bomber Command Association’s 60th Anniversary Symposium) 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Photographs credited to MAP have been reproduced by kind permission of Military Aircraft Photographs. Copies of these, and of many others, may be obtained via http://www.mar.co.uk First published in the UK in 2004 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Typeset by Creative Associates 115 Magdalen Road Oxford OX4 1RS Printed by Advance Book Printing Unit 9 Northmoor Park Church Road Northmoor OX29 5UH 3 CONTENTS RECOLLECTIONS OF A SECRETARY OF STATE FOR 4 DEFENCE – The Rt Hon The Lord Healey CH MBE PC HOW DECISIVE WAS THE ROLE OF ALLIED AIR POWER 17 IN THE WAR IN THE PACIFIC, 1941-1945? by Sqn Ldr S I Richards SUMMARY OF THE MINUTES OF THE SEVENTEENTH 47 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING HELD IN THE ROYAL AIR FORCE CLUB ON 10 JUNE 2003 FEEDBACK 51 DEREK WOOD – AN OBITUARY 55 BOOK REVIEWS 56 PROCEEDINGS OF THE BOMBER COMMAND 82 ASSOCIATION 60TH ANNIVERSARY SYMPOSIUM HELD AT THE RAF MUSEUM, HENDON ON 12 OCTOBER 2002 UNDER THE CHAIRMANSHIP OF AIR MSHL SIR JOHN CURTISS KCB KBE 4 RECOLLECTIONS OF A SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE The Rt Hon The Lord Healey CH MBE PC I should perhaps start by saying that there is no specific theme to what I have to say. -

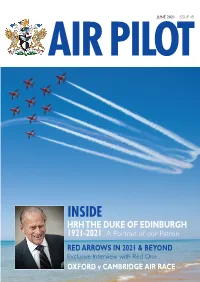

June 2021 Issue 45 Ai Rpi Lo T

JUNE 2021 ISSUE 45 AI RPI LO T INSIDE HRHTHE DUKE OF EDINBURGH 1921-2021 A Portrait of our Patron RED ARROWS IN 2021 & BEYOND Exclusive Interview with Red One OXFORD v CAMBRIDGE AIR RACE DIARY With the gradual relaxing of lockdown restrictions the Company is hopeful that the followingevents will be able to take place ‘in person’ as opposed to ‘virtually’. These are obviously subject to any subsequent change THE HONOURABLE COMPANY in regulations and members are advised to check OF AIR PILOTS before making travel plans. incorporating Air Navigators JUNE 2021 FORMER PATRON: 26 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Duxford His Royal Highness 30 th T&A Committee Air Pilot House (APH) The Prince Philip Duke of Edinburgh KG KT JULY 2021 7th ACEC APH GRAND MASTER: 11 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Henstridge His Royal Highness th The Prince Andrew 13 APBF APH th Duke of York KG GCVO 13 Summer Supper Girdlers’ Hall 15 th GP&F APH th MASTER: 15 Court Cutlers’ Hall Sqn Ldr Nick Goodwyn MA Dip Psych CFS RAF (ret) 21 st APT/AST APH 22 nd Livery Dinner Carpenters’ Hall CLERK: 25 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Weybourne Paul J Tacon BA FCIS AUGUST 2021 Incorporated by Royal Charter. 3rd Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Lee on the Solent A Livery Company of the City of London. 10 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Popham PUBLISHED BY: 15 th Air Pilot Flying Club The Honourable Company of Air Pilots, Summer BBQ White Waltham Air Pilots House, 52A Borough High Street, London SE1 1XN SEPTEMBER 2021 EMAIL : [email protected] 15 th APPL APH www.airpilots.org 15 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Oaksey Park th EDITOR: 16 GP&F APH Allan Winn EMAIL: [email protected] 16 th Court Cutlers’ Hall 21 st Luncheon Club RAF Club DEPUTY EDITOR: 21 st Tymms Lecture RAF Club Stephen Bridgewater EMAIL: [email protected] 30 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Compton Abbas SUB EDITOR: Charlotte Bailey Applications forVisits and Events EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTIONS: The copy deadline for the August 2021 edition of Air Pilot Please kindly note that we are ceasing publication of is 1 st July 2021. -

IL BOMBARDAMENTO STRATEGICO Di Emilio Bonaiti

IL BOMBARDAMENTO STRATEGICO di Emilio Bonaiti “Qualunque cosa si dica, i bombardieri passeranno sempre. L’unica difesa è l’offesa, il che significa che dovrete uccidere donne e bambini più velocemente del nemico, se vorrete salvarvi”. Stanley Baldwin La Grande Guerra - I ‘profeti’ - Gli anni tra le due guerre - La seconda guerra mondiale - La spada - Lo scudo - L’incursione - Finis belli. In The strategic air offensive against Germany, storia ufficiale della Royal Air Force scritta da Charles Webster e Noble Frankland, vi è una chiara definizione del bombardamento strategico: “L’offensiva aerea strategica è un mezzo di attacco diretto contro lo stato nemico, con l’obiettivo di privarlo dei mezzi e della volontà di continuare la guerra. Esso può essere lo strumento che di per sé assicura la vittoria, ovvero il mezzo mediante il quale la vittoria può essere conseguita da altre forze. Esso si distingue da tutti i tipi convenzionali di attacco armato in quanto, a differenza degli altri, può colpire in modo immediato, diretto e distruttivo il cuore stesso del nemico. Pertanto la sua sfera di attività si estende non solo al di sopra, ma anche al di là di quella degli eserciti e delle marine da guerra”. Secondo i manuali il bombardamento strategico, definito anche bombardamento logistico, ha l’obiettivo di ridurre, ritardare o annullare la produzione dei mezzi bellici, dei rifornimenti, delle comunicazioni del nemico allo scopo di annullare la sua volontà di continuare nella lotta. Invero, a giudizio di chi scrive, definizione più esatta, più calzante, sarebbe quella di bombardamento terroristico, attuato allo scopo di distruggere fisicamente la popolazione civile.