Journal 1971

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IN and out of SAAS. G. W. Murray

IN AND OUT OF SAAS IN AN.D OUT OF SAAS BY G. w. MURRAY OST of us are agreed that our mountaineering ought to be rather more than an indiscriminate attack upon the perpendicular. That is to say, we do employ some method in our choice of objective, even if we restrict our assaults to the V£ertausender. Such a selection seems austere but rather too exclusive. Some years ago, when the peak-baggers were at their worst and they saw the glorious sky-lines of Saas and Zermatt only as so many scenic railways, I devised a game far better suited to my dignity and middle age. According to this convention, the Saas valley, from afar, was considered a stronghold to be carried at all hazards while, once an entrance had been forced, it became a prison to be broken out of at no matter what cost of in genuity or agility. A route, once made, was not to be repeated. Half a dozen -vvays, such as the' Col de Stalden,' the Simeli-Sirwolten route, the Rossboden Pass, the Monte Moro, the Adler and the Allalin, had already been done, and so were disqualified. Another obvious one, the Antrona, -vvas closed to us by the Italian Government. The Zwischbergen Pass appeared unworthy of the new idea; moreover, one easy route had to be left to the future in case we found ourselves condemned by old age and the convention to reside in Saas for the rest of our natural lives. But to find a seventh and better route professional advice and assistance became necessary, so I enlisted as our ally Oscar Supersaxo. -

Tourenberichte 1955 Und 1956

Tourenberichte 1955 und 1956 Objekttyp: Group Zeitschrift: Jahresbericht / Akademischer Alpen-Club Zürich Band (Jahr): 60-61 (1955-1956) PDF erstellt am: 30.09.2021 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch Tourenberichte 1955 und 1956 A. Berichte der aktiven Mitglieder D/Wer Sommer 1955: Salbitschijen (S-Grat), Bergseeschijen (S-Grat), Schijenstock (S-Grat), Zinalrothorn (Rothorngrat), Dom, Wellenkuppe, Großglockner, Marmolata (W-Grat), Rosenlauistock (W-Kante), Korsikatouren. Sommer 1956: Pa»/ AfemAerz: Winter 1955: Piz Gendusas, Piz Medel, Cima di Camadre, Cuolm Val-Piz Calmot, Fellilücke-Piz Tiarms (trav.), Piz Borel-Cadlimo-Paß Nalps, Piz Malèr (V), Crispaltlücke-Piz Giuf-Krützlipaß-Oberalpstock-Piz Cavardiras, Piz Sol, Piz Platta, Grand Combin, Petit Combin-Col des Avouillons. -

FUTURE FOREST the BLACK WOOD RANNOCH, SCOTLAND

Gunnar’s Tree with the community, Nov. 23, 2013 (Collins & Goto Studio, 2013). FUTURE FOREST The BLACK WOOD RANNOCH, SCOTLAND Tim Collins and Reiko Goto Collins & Goto Studio, Glasgow, Scotland Art, Design, Ecology and Planning in the Public Interest with David Edwards Forest Research, Roslin, Scotland The Research Agency of the Forestry Commission Developed with: The Rannoch Paths Group Anne Benson, Artist, Chair, Rannoch and Tummel Tourist Association, Loch Rannoch Conservation Association. Jane Dekker, Rannoch and Tummel Tourist Association. Jeannie Grant, Tourism Projects Coordinator, Rannoch Paths Group. Bid Strachan, Perth and Kinross Countryside Trust. The project partners Charles Taylor, Rob Coope, Peter Fullarton, Tay Forest District, Forestry Commission Scotland. David Edwards and Mike Smith, Forest Research, Roslin. Paul McLennan, Perth and Kinross Countryside Trust. Richard Polley, Mark Simmons, Arts and Heritage, Perth and Kinross Council. Mike Strachan, Perth and Argyll Conservancy, Forestry Commission Scotland. Funded by: Creative Scotland: Imagining Natural Scotland Programme. The National Lottery / The Year of Natural Scotland. The Landscape Research Group. Forestry Commission Scotland. Forest Research. Future Forest: The Black Wood, Rannoch, Scotland Tim Collins, Reiko Goto and David Edwards Foreword by Chris Quine The Landscape Research Group, a charity founded in 1967, aims to promote research and understanding of the landscape for public benefit. We strive to stimulate research, transfer knowledge, encourage the exchange of ideas and promote practices which engage with landscape and environment. First published in UK, 2014 Forest Research Landscape Research Group Ltd Northern Research Station PO Box 1482 Oxford OX4 9DN Roslin, Midlothian EH25 9SY www.landscaperesearchgroup.com www.forestry.gov.uk/forestresearch © Crown Copyright 2014 ISBN 978-0-9931220-0-2 Paperback ISBN 978-0-9931220-1-9 EBook-PDF Primary funding for this project was provided by Creative Scotland, Year of Natural Scotland. -

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes 2–5 Sackville Street Piccadilly London W1S 3DP +44 (0)20 7439 6151 [email protected] https://sotherans.co.uk Mountaineering 1. ABBOT, Philip Stanley. Addresses at a Memorial Meeting of the Appalachian Mountain Club, October 21, 1896, and other 2. ALPINE SLIDES. A Collection of 72 Black and White Alpine papers. Reprinted from “Appalachia”, [Boston, Mass.], n.d. [1896]. £98 Slides. 1894 - 1901. £750 8vo. Original printed wrappers; pp. [iii], 82; portrait frontispiece, A collection of 72 slides 80 x 80mm, showing Alpine scenes. A 10 other plates; spine with wear, wrappers toned, a good copy. couple with cracks otherwise generally in very good condition. First edition. This is a memorial volume for Abbot, who died on 44 of the slides have no captioning. The remaining are variously Mount Lefroy in August 1896. The booklet prints Charles E. Fay’s captioned with initials, “CY”, “EY”, “LSY” AND “RY”. account of Abbot’s final climb, a biographical note about Abbot Places mentioned include Morteratsch Glacier, Gussfeldt Saddle, by George Herbert Palmer, and then reprints three of Abbot’s Mourain Roseg, Pers Ice Falls, Pontresina. Other comments articles (‘The First Ascent of Mount Hector’, ‘An Ascent of the include “Big lunch party”, “Swiss Glacier Scene No. 10” Weisshorn’, and ‘Three Days on the Zinal Grat’). additionally captioned by hand “Caution needed”. Not in the Alpine Club Library Catalogue 1982, Neate or Perret. The remaining slides show climbing parties in the Alps, including images of lady climbers. A fascinating, thus far unattributed, collection of Alpine climbing. -

View from the Summit Over the Italian Side of Mont Blanc Is Breathtaking! Descent Via Normal Route

Compagnie des Guides de Chamonix 190 place de l’église - 74400 Chamonix – France - Tél : + 33 (0)4 50 53 00 88 www.chamonix-guides.com - e-mail : [email protected] AIGUILLE VERTE - PRIVE - TISON Duration: 5 days Level: Price from: 2 485 € The Chamonix Compagnie des Guides offers you a collection of programmes to climb the legendary peaks of the Alps. We have selected a route together with a specific preparatory package for each peak. Each route chosen is universally recognised as unmissable. Thanks to our unique centre of expertise, we can also guide you on other routes. So don’t hesitate to dream big, as our expertise is at your service to help you make your dreams come true. The Aiguille Verte is THE legendary peak in the Mont Blanc Massif. The celebrated mountaineer and writer Gaston Rébuffat contributed significantly to this reputation when he said of it: “Before the Verte one is a mountaineer, on the Verte one becomes a ‘Montagnard’ (mountain dweller)”. It is certainly true that there are no easy routes on this peak and each face is a significant challenge. The south side of the Aiguille Verte is an outstanding snow route that follows the Whymper Couloir for over 700 metres. This is unquestionably one of the most beautiful routes in the massif, and we offer a four-day programme for its ascent. ITINERARY Day 1 and Day 2 : Acclimatisation routes with a night in the Torino Hut (3370m) These first two days give your body the essential time it requires to adapt to altitude. -

Switzerland Welcome to Switzerland

Welcome to Switzerland A complete guide for your stay in Lausanne during the 15th CSCWD Conference Table of Contents I. Switzerland and the Lausanne region II. Access to Lausanne III. Restaurants in Lausanne IV. Transports in Lausanne V. Useful Information VII. Your venue: The Olympic Museum VIII. Tourism Activities I. Switzerland and the Lausanne region By its central geographical location, Switzerland is an ideal international destination for business, incentive and leisure travel. It is a country with many different facets. It unites an impressive variety of landscapes in a small geographical area and benefits from an exceptional natural heritage. As an important centre for communication and transport between the countries of Northern and Southern Europe, it has a common frontier with Germany, France, Italy, and the Principality of Liechtenstein. The Alpine Arc, just a few kilometers away from Lausanne, features some of the finest mountain peaks like the Matterhorn, Mont Blanc or the Jungfrau, and spectacular passes: Grimsel, St Gotthard, Simplon and Great St Bernard. These natural assets are further enhanced by security and dependability, Swiss values par excellence . The second largest city on the shore of Lake Geneva, Lausanne combines the dynamics of a business town with its ideal location as a holiday resort. Sport and culture are a golden rule in this Olympic capital. Nature, historic town, contemporary architecture, and exceptional surroundings: the Olympic capital is a model of the art of living and of cultural events. No need to wear out your shoes to visit the town and its region. A dense public transport network gives you the freedom to go from the lakeside to the trendy neighborhoods within minutes. -

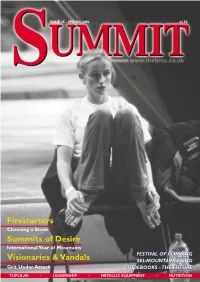

Firestarters Summits of Desire Visionaries & Vandals

31465_Cover 12/2/02 9:59 am Page 2 ISSUE 25 - SPRING 2002 £2.50 Firestarters Choosing a Stove Summits of Desire International Year of Mountains FESTIVAL OF CLIMBING Visionaries & Vandals SKI-MOUNTAINEERING Grit Under Attack GUIDEBOOKS - THE FUTURE TUPLILAK • LEADERSHIP • METALLIC EQUIPMENT • NUTRITION FOREWORD... NEW SUMMITS s the new BMC Chief Officer, writing my first ever Summit Aforeword has been a strangely traumatic experience. After 5 years as BMC Access Officer - suddenly my head is on the block. Do I set out my vision for the future of the BMC or comment on the changing face of British climbing? Do I talk about the threats to the cliff and mountain envi- ronment and the challenges of new access legislation? How about the lessons learnt from foot and mouth disease or September 11th and the recent four fold hike in climbing wall insurance premiums? Big issues I’m sure you’ll agree - but for this edition I going to keep it simple and say a few words about the single most important thing which makes the BMC tick - volunteer involvement. Dave Turnbull - The new BMC Chief Officer Since its establishment in 1944 the BMC has relied heavily on volunteers and today the skills, experience and enthusi- District meetings spearheaded by John Horscroft and team asm that the many 100s of volunteers contribute to climb- are pointing the way forward on this front. These have turned ing and hill walking in the UK is immense. For years, stal- into real social occasions with lively debates on everything warts in the BMC’s guidebook team has churned out quality from bolts to birds, with attendances of up to 60 people guidebooks such as Chatsworth and On Peak Rock and the and lively slideshows to round off the evenings - long may BMC is firmly committed to getting this important Commit- they continue. -

512J the Alpine Journal 2019 Inside.Indd 422 27/09/2019 10:58 I N D E X 2 0 1 9 423

Index 2019 A Alouette II 221 Aari Dont col 268 Alpi Biellesi 167 Abram 28 Alpine Journal 199, 201, 202, 205, 235, 332, 333 Absi 61 Alps 138, 139, 141, 150, 154, 156, 163, 165, 179 Aconcagua 304, 307 Altamirano, Martín 305 Adams, Ansel 178 Ama Dablam 280, 282 Adam Smith, Janet 348 American Alpine Journal 298 Adda valley 170 American Civil War 173 Adhikari, Rabindra 286 Amery, Leo 192 Aemmer, Rudolph 242 Amin, Idi 371 Ahlqvist, Carina 279 Amirov, Rustem 278 Aichyn 65 Ancohuma 242 Aichyn North 65, 66 Anderson, Rab 257 Aiguille Croux 248 Andes 172 Aiguille d’Argentière 101 Androsace 222 Aiguille de Bionnassay 88, 96, 99, 102, 104, 106, Angeles, Eugenio 310 109, 150, 248 Angeles, Macario 310 Aiguille de l’M 148 Angel in the Stone (The) Aiguille des Ciseaux 183 review 350 Aiguille des Glaciers 224 Angsi glacier 60 Aiguille des Grands Charmoz 242 Anker, Conrad 280, 329 Aiguille du Blaitière 183 Annapurna 82, 279, 282, 284 Aiguille du Goûter 213 An Teallach 255 Aiguille du Midi 142, 146, 211, 242 Antoinette, Marie 197 Aiguille du Moine 146, 147 Anzasca valley 167 Aiguille Noire de Peuterey 211 Api 45 Aiguilles Blaitière-Fou 183 Ardang 62, 65 Aiguilles de la Tré la Tête 88 Argentère 104 Aiguilles de l’M 183 Argentière glacier 101, 141, 220 Aiguilles Grands Charmoz-Grépon 183 Argentière hut 104 Aiguilles Grises 242 Arjuna 272 Aiguille Verte 104 Arnold, Dani 250 Ailfroide 334 Arpette valley 104 Albenza 168 Arunachal Pradesh 45 Albert, Kurt 294 Ashcroft, Robin 410 Alborz 119 Askari Aviation 290 Alexander, Hugh 394 Asper, Claudi 222 Allan, Sandy 260, -

Sika at Work Matterhorn Glacier Paradise

Source: MLG Metall SIKA AT WORK MATTERHORN GLACIER PARADISE, SWITZERLAND BONDED BIPV SYSTEM AT 3,883 METERS WITH Sikasil SG®-500 MATTERHORN GLACIER PARADISE, SWITZERLAND PROJECT DESCRIPTION SIKA SOLUTION At 3,883 meters above sea level in the Valais Alps, the Matterhorn Sikasil® SG-500 Glacier Paradise tourist center offers a breathtaking view of 38 four- thousanders in the Swiss, Italian and French Alps. Located on the Klein PROJECT FACTS Matterhorn, the tourist center attracts around half a million visitors Project name: Matterhorn Glacier Paradise tourist center from all over the world every year and serves as starting point for moun- Location: Zermatt, Switzerland taineers wishing to explore the Zermatt ski area. Project client: Zermatt Bergbahnen AG Planning: Peak Architekten / Burri Müller Partner The project clients gave the utmost priority to environmental compati- Metal construction: MLG Metall Planung AG bility and energy efficiency of the construction. The center was built -ac Module supplier: 3S Industries AG cording to the latest ecological standards. The entire heating and ventila- Energy performance: 37,000 kWh p.a. tion system is solar-powered. To achieve this the south facade has been Completion: Spring 2009 clad with a building integrated photovoltaic system that is the first of its kind to be installed at this altitude in Europe. Bonding the 108 specially FIND MORE SIKA REFERENCES developed high-performance ultra-weather-resistant PV modules calls for a superlative adhesive, capable of readily withstanding temperatures of -40 °C to +30 °C and wind speeds of up to 300 km/h. Sikasil® SG-500 met the rigorous requirements. -

CC J Inners 168Pp.Indd

theclimbers’club Journal 2011 theclimbers’club Journal 2011 Contents ALPS AND THE HIMALAYA THE HOME FRONT Shelter from the Storm. By Dick Turnbull P.10 A Midwinter Night’s Dream. By Geoff Bennett P.90 Pensioner’s Alpine Holiday. By Colin Beechey P.16 Further Certifi cation. By Nick Hinchliffe P.96 Himalayan Extreme for Beginners. By Dave Turnbull P.23 Welsh Fix. By Sarah Clough P.100 No Blends! By Dick Isherwood P.28 One Flew Over the Bilberry Ledge. By Martin Whitaker P.105 Whatever Happened to? By Nick Bullock P.108 A Winter Day at Harrison’s. By Steve Dean P.112 PEOPLE Climbing with Brasher. By George Band P.36 FAR HORIZONS The Dragon of Carnmore. By Dave Atkinson P.42 Climbing With Strangers. By Brian Wilkinson P.48 Trekking in the Simien Mountains. By Rya Tibawi P.120 Climbing Infl uences and Characters. By James McHaffi e P.53 Spitkoppe - an Old Climber’s Dream. By Ian Howell P.128 Joe Brown at Eighty. By John Cleare P.60 Madagascar - an African Yosemite. By Pete O’Donovan P.134 Rock Climbing around St Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai Desert. By Malcolm Phelps P.142 FIRST ASCENTS Summer Shale in Cornwall. By Mick Fowler P.68 OBITUARIES A Desert Nirvana. By Paul Ross P.74 The First Ascent of Vector. By Claude Davies P.78 George Band OBE. 1929 - 2011 P.150 Three Rescues and a Late Dinner. By Tony Moulam P.82 Alan Blackshaw OBE. 1933 - 2011 P.154 Ben Wintringham. 1947 - 2011 P.158 Chris Astill. -

(0)27 966 01 01 Sunnegga Furi Furi Breuil-Cervinia

DE FR EN IT SUNNEGGA-ROTHORN 7 Standard 16 Chamois 28 White Hare 37 Riffelhorn MATTERHORN GLACIER 56 Kuhbodmen 65 Rennstrecke / Skimovie SOMMERSKI / BREUIL-CERVINIA 11 Gran Roc-Pre de Veau 39 Gaspard 9 Baracon PANORAMAKARTE / PLAN PANORAMIQUE / 1 Untere National 8 Obere National 17 Marmotte 29 Kelle 38 Rotenboden PARADISE 57 Aroleid 66 Theodulsee THEODULGLETSCHER 2 Cretaz 12 Muro Europa 46 Bontadini 2 10 Du Col PANORAMIC MAP / MAPPA PANORAMICA. 2 Ried 9 Tufteren 18 Arbzug 30 Mittelritz 39 Riffelalp 49 Bielti 58 Hermetji 67 Garten Buckelpiste 80 Testa Grigia 3 Plan Torrette-Pre de Veau 13 Ventina-Cieloalto 47 Fornet 2 11 Gran Sometta 2a Riedweg (Quartier- 10 Paradise 19 Fluhalp 31 Platte 40 Riffelboden 50 Blatten 59 Tiefbach 68 Tumigu 81 Führerpiste 3.0 Pre de Veau-Pirovano 14 Baby Cretaz 59 Pista Nera del Cervino 12 Gran Lago strasse, keine Skipiste) 11 Rotweng 32 Grieschumme 41 Landtunnel 51 Weisse Perle 60 Momatt 69 Matterhorn 82 Mittelpiste 3.00 Pirovano-Cervinia 16 Cieloalto-Cervinia 60 Snowpark Cretaz 14 Tunnel 2017/2018 3 Howette 12 Schneehuhn GORNERGRAT 33 Triftji 42 Schweigmatten 52 Stafelalp 61 Skiweg 70 Schusspiste 83 Plateau Rosa 3bis Falliniere 21 Cieloalto 1 62 Gran Roc 15 E. Noussan 4 Brunnjeschbord 13 Downhill 25 Berter 34 Stockhorn 43 Moos 53 Oberer Tiefbach 62 Furgg – Furi 71 Theodulgletscher 84 Ventina Glacier 4 Plan Torrette 22 Cieloalto 2 15a Sigari 5 Eisfluh 14 Kumme 26 Grünsee 35 Gifthittli 44 Hohtälli 54 Hörnli 63 Sandiger Boden 72 Furggsattel 85 Matterhorn glacier 5 Plan Maison-Cervinia 24 Pancheron VALTOURNENCHE -

Mountaineering Ventures

70fcvSs )UNTAINEERING Presented to the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO LIBRARY by the ONTARIO LEGISLATIVE LIBRARY 1980 v Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/mountaineeringveOObens 1 £1. =3 ^ '3 Kg V- * g-a 1 O o « IV* ^ MOUNTAINEERING VENTURES BY CLAUDE E. BENSON Ltd. LONDON : T. C. & E. C. JACK, 35 & 36 PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. AND EDINBURGH PREFATORY NOTE This book of Mountaineering Ventures is written primarily not for the man of the peaks, but for the man of the level pavement. Certain technicalities and commonplaces of the sport have therefore been explained not once, but once and again as they occur in the various chapters. The intent is that any reader who may elect to cull the chapters as he lists may not find himself unpleasantly confronted with unfamiliar phraseology whereof there is no elucidation save through the exasperating medium of a glossary or a cross-reference. It must be noted that the percentage of fatal accidents recorded in the following pages far exceeds the actual average in proportion to ascents made, which indeed can only be reckoned in many places of decimals. The explanation is that this volume treats not of regular routes, tariffed and catalogued, but of Ventures—an entirely different matter. Were it within his powers, the compiler would wish ade- quately to express his thanks to the many kind friends who have assisted him with loans of books, photographs, good advice, and, more than all, by encouraging countenance. Failing this, he must resort to the miserably insufficient re- source of cataloguing their names alphabetically.