Journey to the Centre of the Text. on Translating Verne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

80 Days Adaptations

TABLE OF CONTENTS About ATC . 1 Introduction to the Play . 2 THIS IS Synopsis . 2 Meet the Characters . 3 DEFINITELY Meet the Creators . 5 NOT THE An Interview with Mark Brown . 6 QUIET LIFE From Page to Stage: 80 Days Adaptations . 7 I WAS 80 Days: The Journey . 9 Cultural Context: 19th Century Britain . 15 LOOKING FOR. – Passepartout, References and Glossary . 17 Around the World in 80 Days Discussion Questions and Activities . 23 Around the World in 80 Days Play Guide written and compiled by Katherine Monberg, ATC Literary Associate; April Jackson, Tucson Education Manager; and Amber Justmann, Literary Intern . Discussion questions and activities provided by April Jackson, Tucson Education Manager; Amber Tibbitts, Phoenix Education Manager; and Bryanna Patrick, Education Associate . SUPPORT FOR ATC’S EDUCATION AND COMMUNITY PROGRAMMING HAS BEEN PROVIDED BY: APS JPMorgan Chase The Lovell Foundation Arizona Commission on the Arts John and Helen Murphy Foundation The Marshall Foundation Bank of America Foundation National Endowment for the Arts The Maurice and Meta Gross Foundation Blue Cross Blue Shield Arizona Phoenix Office of Arts and Culture The Max and Victoria Dreyfus Foundation City of Glendale PICOR Charitable Foundation The Stocker Foundation Community Foundation for Southern Arizona Rosemont Copper The William L . and Ruth T . Pendleton Cox Charities Stonewall Foundation Memorial Fund Downtown Tucson Partnership Target Tucson Medical Center Enterprise Holdings Foundation The Boeing Company Tucson Pima Arts Council Ford Motor Company Fund The Donald Pitt Family Foundation Wells Fargo Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Foundation The Johnson Family Foundation, Inc . ABOUT ATC Arizona Theatre Company is a professional, not-for-profit theatre company . -

Download The

DAVID LINDSAY'S A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS ALLEGORICAL DREAM FANTASY AS A LITERARY MODE by JACK S CHOFIELD B.A., University of Birmingham, 1969 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, 19 72 tn presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date Abstract David Lindsay's A Voyage to Arcturus must be read as an allegorical dream fantasy for its merit to be correctly discerned. Lindsay's central themes are introduced in a study of the man and his work. (Ch. 1). These themes are found to be common in allegorical dream fantasy, the phenomen- ological background of which is established (Ch. 2). A distinction can then be drawn between fantasy and romance, so as to define allegorical dream fantasy as a literary mode (Ch. 3). After the biographical, theoretical and literary backgrounds of A Voyage have been established in the first three chapters, the second three chapters explicate the structure of the book as an allegorical dream fantasy. -

Volume 1 (2008-2009)

V E R N I A N A Jules Verne Studies – Etudes Jules Verne Vol. 1 2008-2009 Initial capital “V” copyright ©1972 Richard Aeschlimann, Yverdon- les-Bains (Switzerland). Reproduced with his permission. La lettrine “V” de couverture est copyright ©1972 Richard Aeschlimann, Yverdon-les-Bains (Suisse). Elle est reproduite ici avec son autorisation. V E R N I A N A Jules Verne Studies – Etudes Jules Verne Vol. 1 2008-2009 Editorial Board – Comité de rédaction William Butcher Daniel Compère Volker Dehs Arthur B. Evans Terry Harpold Jean-Michel Margot Walter James Miller Garmt de Vries-Uiterweerd ISSN : 1565-8872 V E R N I A N A Jules Verne Studies – Etudes Jules Verne Vol. 1 - 2008-2009 Editorial The Editors ― “Dr. Zvi Har’El (December 14, 1949-February 2, 2008) and International Jules Verne Studies - A Tribute” i Le Comité de redaction ― “Dr. Zvi Har’El (14 décembre 1949-2 février 2008) et les Etudes internationales Jules Verne - Un Hommage” iii Daniel Compère ― “Editorial (Français)” v Daniel Compère ― “Editorial (English)” vii Articles Walter James Miller ― “As Verne Smiles” 1 Arthur B. Evans ― “Jules Verne in English: A Bibliography of Modern Editions and Scholarly Studies” 9 Brian Taves ― “Expedition Into a Novel” 23 Terry Harpold ― “Verne’s Errant Readers: Nemo, Clawbonny, Michel Dufrénoy” 31 Ian Thompson & Philippe Valetoux – “Jules Verne’s visits to Gibraltar in 1878 and 1884” 43 Brian Taves - “Opening the Sources of The Kip Brothers: A Generic Interpretation” 51 Reviews Dave Bonte ― “Le Voyage à travers l’impossible (1882) en néerlandais” 65 Upcoming Conferences and Symposia Conférences et Symposia à venir The 2009 Eaton Science Fiction Conference - Extraordinary Voyages: Jules Verne 67 and Beyond - April 30-May 3, 2009 - University of California, Riverside Index of Authors and Editorial Board Members - Index des auteurs et membres 69 du Comité de rédaction ISSN : 1565-8872 Dr. -

Following in the Footsteps of Sir Walter Scott Seventeen Days In

Following in the Footsteps of Sir Walter Scott: Eighteen Days in Scotland Lingwei Meng Göttingen November 2016 For Prof. Dr. Barbara Schaff Dr. Kirsten Sandrock Contents Introduction......................................................................................................................................... 1 First Day: Callaner.............................................................................................................................. 2 Second Day: Rob Roy’s Grave and Ledard Waterfall........................................................................ 3 Third Day: Loch Katrine - Inversnaid - Glasgow Cathedral.............................................................. 6 Fourth Day: Stirling Castle............................................................................................................... 10 Fifth Day: Impression on Edinburgh.................................................................................................13 Sixth Day: 25 George Square............................................................................................................15 Seventh Day: Old Site of Tolbooth and St Giles’ Cathedral.............................................................17 Eighth day: A City Tour.....................................................................................................................20 Ninth Day: Old Site of the Mercat Cross and Lady Stair’s Close ................................................22 Tenth Day: St. Andrews................................................................................................................... -

Lewintro.Pdf

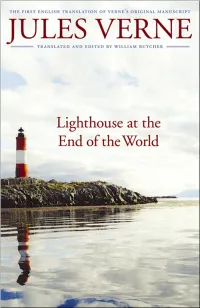

7>HDC;GDCI>:GHD;>B6<>C6I>DC JULES VERNE Lighthouse at the End of theWorld Le Phare du bout du monde The First English Translation of Verne’s Original Manuscript Translated and edited by William Butcher JC>K:GH>IND;C:7G6H@6EG:HH•A>C8DAC Publication of this book was made possible by a grant from The Florence Gould Foundation. Le Phare du bout du monde © Les Éditions internationales Alain Stanké, 1999. © Editions de l’Archipel. Translation and critical apparatus © 2007 by William Butcher. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Verne, Jules, 1828–1905. [Le phare du bout du monde. English] Lighthouse at the end of the world = Le phare du bout du monde : the first English translation of Verne’s original manuscript / Jules Verne ; translated and edited by William Butcher. p. cm. — (Bison frontiers of imagination) Includes bibliographical references. isbn-13: 978-0-8032-4676-8 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-13: 978-0-8032-6007-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) I. Butcher, William, 1951– II. Title. III. Title: Le phare du bout du monde. pq2469.p4e5 2007 843'.8—dc22 2007001717 Set in Adobe Garamond by Kim Essman. Designed by R. W. Boeche. contents Introduction vii A Chronology of Jules Verne xxxiii Map of Staten Island xxxix 1.Inauguration 1 2. Staten Island 10 3. The Three Keepers 19 4.Kongre's Gang 30 5. The Schooner Maule 41 6. At Elgor Bay 50 7.The Cavern 61 8. Repairing the Maule 70 9.Vasquez 79 10.After the Wreck 89 11.The Wreckers 99 12. -

The British Public in a Shrinking World: Civic Engagement with the Declining Empire, 1960-1970

The British Public in a Shrinking World: Civic Engagement with the Declining Empire, 1960-1970 Anna Bocking Welch PhD University of York Department of History September 2012 Abstract This thesis analyses how the British public‘s interactions with the peoples and places of the empire and Commonwealth changed as a result of decolonization. Its central concern is to determine how issues relating to the empire and its decline became part of everyday ‗local‘ experiences within British associational life between 1960 and 1970. It links a rich scholarly tradition of research on the domestic experience of Britain‘s empire to a new and emerging field of research that seeks to understand the institutional and associational makeup of the interconnected postwar world. Chapter One looks at the activities of the Royal Commonwealth Society to assess the afterlife of empire as it was lived by those who had been the most involved. Chapter Two looks at the international work of the Women‘s Institute in order to consider how groups without a specific Commonwealth remit engaged with the spaces of the declining empire. Chapter Three focuses on an individual enthusiast, Charles Chislett, assessing how the personal experiences of one man might resonate across local networks of sociability and public service. Chapters Four and Five on the United Nations Freedom from Hunger Campaign and Christian Aid consider humanitarian engagements with the decolonizing empire, analysing how international and imperial frameworks overlapped in religious and secular practices of aid and development. Using these case studies, the thesis questions the extent to which the impact of decolonization was necessarily traumatic for the British public by considering alternate, optimistic experiences of international friendship, philanthropy and education taking place within civil society. -

Jules Verne the Biography William Butcher Foreword by Arthur C

4 Jules Verne The Biography William Butcher Foreword by Arthur C. Clarke 7 Abbreviations ADF: Marguerite Allotte de la Fuÿe, Jules Verne JES: Verne, Journey to England and Scotland BSJV: Bulletin de la Société Jules Verne CNM: Charles-Noël Martin, La Vie et l’œuvre de Jules Verne (The Life and Works of Jules Verne) Int.: Entretiens avec Jules Verne (Interviews) JD: Joëlle Dusseau, Jules Verne JJV: Jean Jules-Verne, Jules Verne JVEST: Jean-Michel Margot (ed.), Jules Verne en son temps (Jules Verne in his Time) Lemire: Charles Lemire, Jules Verne MCY: “Memories of Childhood and Youth” OD: Olivier Dumas, Voyage à travers Jules Verne (Journey through Jules Verne) Poems: Poésies inédites (Unpublished Poems) PV: Philippe Valetoux, Jules Verne: En mer et contre tous (Jules Verne: All at sea and odds) RD: Raymond Ducrest de Villeneuve, untitled biography St M.: Verne’s list of journeys on the St Michel II and III TI: Théâtre inédit (Unpublished Plays) 291 Appendices A: Home Addresses Date Address 8 February 1828 Third floor, 4 Rue de Clisson, Nantes Late 1828 or early 1829 Second floor, 2 Quai Jean Bart October 1834 Mme Sambin’s pension, 5 Place du Bouffay About 1837 29 Rue des Réformés, Chantenay 3 October 1837 or St Stanislas School October 1836 About 1840 Second floor, 6 Rue Jean-Jacques Rousseau October 1840 St Donatien Junior Seminary 11 July 1848 (until 3 Probably near Henri Garcet’s, Fifth August) Arrondissement, Paris 12 November 1848 About fifth floor, 24 Rue de l’Ancienne Comédie, Sixth March 1849 Third floor, 24 Rue de l’Ancienne Comédie, -

Projets De Recherche

Projets de recherche: Biographie; editer un rassemblement d’articles critiques francais ; traductions ; éditions critiques Participations à des colloques: Publications: * The Mysterious Island, introduction, critical material and notes (paperback and hardback, Wesleyan University Press, February 2002); extracts appeared in Nautilus, Summer 2001, no. 1, pp. 5-9) * Journey to the Centre of the Earth, translated with a note on the text and translation, with an introduction by Michael Crichton (The Folio Society, July 2001, gross takings to date £250,000); also published June 2001 with critical apparatus by the online subscription service, Questia (http:// www.questia.com/) * Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas, translation, introduction and critical edition (Oxford University Press, 3rd revised edn 2001) * Around the World in Eighty Days, translation, introduction and critical edition (OUP, 3rd revised edn 1999); serialised on Book at Bedtime, BBC Radio 4 and World Service, read by Robert Powell, 7-18 May 2001; also published with critical apparatus by online subscription service, Questia (http://www.questia.com/), Sept. 2001 * Backwards to Britain, Jules Verne, consultant editor and introduction (Chambers, Edinburgh, 1992). * Journey to the Centre of the Earth, translation, introduction and critical edition (OUP, 1992). * Humbug: The American Way of Life, Jules Verne, revised by Michel Verne, translation, introduction and critical edition (Acadian, 1991). * Mississippi Madness: Canoeing the Mississippi-Missouri (co-author) (Oxford Illustrated Press and Sheradin House, New York, 1990). * Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Self: Space and Time in the “Voyages extra-ordinaires”, with a Foreword by Ray Bradbury (Macmillan, London, and St Martin’s Press, New York, 1990). -

Newsletter Number 65

The Palaeontology Newsletter Contents 65 Association Business 2 News 16 Association Meetings 18 From our correspondents The Lost Column 22 Missing values and Stratigraphy 29 PalaeoMath 101: Groups II 36 Meeting Reports 50 Advert: William Spring 61 The reflections of another taxi member 62 Soapbox: ‘Ask a Biologist’ 63 Future meetings of other bodies 66 Reporter: Palaeontology in 4D 76 Outside The Box: Science Communication 81 Geoconservation and Geoeducation 83 Advert: Computer-aided palaeontology 87 Sylvester-Bradley Reports 88 Book Reviews 111 Discounts for PalAss members 129 Palaeontology vol 50 parts 3 & 4 130–132 Graduate opportunities 133 Reminder: The deadline for copy for Issue no 66 is 8th October 2007. On the Web: <http://www.palass.org/> ISSN: 0954-9900 Newsletter 65 2 Association Business Trustees Annual Report 2006 Nature of the Association. The Palaeontological Association is a Charity registered in England, Charity Number 276369. Its Governing Instrument is the Constitution adopted on 27th February 1957, amended on subsequent occasions as recorded in the Council Minutes. The aim of the Association is to promote research in Palaeontology and its allied sciences by (a) holding public meetings for the reading of original papers and the delivery of lectures, (b) demonstration and publication, and (c) by such other means as the Council may determine. Trustees (Council Members) are elected by vote of the Membership at the Annual General Meeting. The contact address of the Association is c/o The Executive Officer, Dr T. J. Palmer, Institute of Geography and Earth Sciences, University of Wales, Aberystwyth, SY23 3DB, Wales, UK. Trustees. The following members were elected to serve on Council at the AGM on 20th December 2006: President: Professor M. -

JULES VERNE Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas

JULES VERNE Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas Translated with an Introduction and Notes by WILLIAM BUTCHER 1 ‘I am going to sink it.' ‘You will not!' ‘I will,’ he coldly replied. ‘Do not take it on yourself to judge me, monsieur.’ French naturalist Dr Aronnax embarks on an expedition to hunt down a sea monster, but discovers instead the Nautilus, a self-contained world built by its enigmatic captain. To- gether Nemo and Aronnax explore the underwater marvels of the globe, undergo a transcen- dent experience in the ruins of Atlantis, and plant a black flag at the South Pole. But Nemo’s mission is finally revealed to be one of revenge—and his methods coldly efficient. Verne’s classic novel has left a profound mark on the twentieth century. Its themes are universal, its style alternately humorous and grandiose, its construction masterly. This new and unabridged translation by the father of Verne studies brilliantly conveys the range of this seminal work. The volume also contains unpublished information about the novel’s genesis. ‘by far the best translations/critical editions available . known internationally as a topnotch scholar’ Science-Fiction Studies 2 OXFORD WORLD’S CLASSICS TWENTY THOUSAND LEAGUES UNDER THE SEAS Jules Verne was born in Nantes in 1828, the eldest of five children in a prosperous family of French, Breton, and Scottish extraction. His early years were happy apart from an unfulfilled passion for his cousin Caroline. Literature always attracted him and while taking a law degree in Paris he wrote a number of plays. His first two books, entitled Journey to Scot- land and Paris in the Twentieth Century, were not published in his lifetime. -

“Les Indes Noires”: the Scottish Context1 Ian Thompson2

Verniaan 51 “Les Indes noires”: the Scottish context1 Ian Thompson2 Towards midnight on Friday 26 August 1859, the Caledonian Railway express from Liverpool pulled into Edinburgh’s Lothian Road terminus. As the smoke and steam cleared, two men emerged. One of them was Jules Verne, then aged 31 and practically unknown but who was to become the fourth most translated author in the world. With him was a musician friend, Aristide Hignard, who was to be Verne’s companion on their brief tour of Scotland. As he stepped onto the platform so Verne took a crucial step in his lifelong love affair with Scotland and the Scots. Few Scots today are aware of the famous author’s special connection with their country. In fact, Verne claimed Scottish ancestry on his mother’s side, from a fifteenth century archer, N. Allott, in the service of Louis XI of France. Having served the king with distinction, he was awarded the noble title of ‘de la Fuÿe’, signifying the right to own a dovecot, and the family name became ‘Allotte de la Fuÿe’. Moreover, from his youth, Verne had revelled in the works of Sir Walter Scott, popularised in Europe by the Romantic movement, which Verne had read avidly in translation. He had delved widely into Scottish history and as a Breton, sympathised with the notion of Scotland, like Ireland, as being downtrodden and exploited by the English. This absorption with all things Scottish is reflected in his fiction. Two novels are entirely set in Scotland, Les Indes noires and Le Rayon vert, and three others are located in part in Scotland. -

Intertextuality and Verne's Norway

Intertextuality and Verne’s Norway. The origin of Un Billet de loterie (1886) Per Johan Moe Lasting impressions Jules Verne visited Norway in 1861, but in order to write a book about the country, he would not have had to. He could have based this work on external material, as he had done in several of his novels set in places he never saw with his own eyes. Evidently, he was not in a hurry to publish a novel based on his impressions from Norway since he and his publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel waited 25 years before the novel about the Norwegian ‘Lottery ticket’ came out. Truly, though, the journey made a lasting impression on the young author. In the seven years that followed the Nordic experience and after signing a contract for his VE series, every novel following the opening title Cinq Semaines en ballon contained references to Norway.1 When his publisher finally decided the time was right, in the mid 1880s, it was not only the novel Un Billet de loterie (BL) that was printed. The house of Hetzel chose to publish a series with Scandinavian material: three novels in a row. In 1885, the year before BL, came L’Épave du Cynthia2 - a story set in Norway, Sweden and arctic surroundings. Like BL, it appears to have drawn on information from the magazine Le Tour du monde, and also like BL, it makes clear allusions to old Nordic myths and legends3. Also printed in 1886, the same publication year as BL, was the novel about Robur-le-Conqurérant, which in the opening chapter, among numerous other observations, reports “l’Albatros” beyond the Arctic circle in Scandinavia.