Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Succeeding Succession: Cosmic and Earthly Succession B.C.-17 A.D

Publication of this volume has been made possiblej REPEAT PERFORMANCES in partj through the generous support and enduring vision of WARREN G. MOON. Ovidian Repetition and the Metamorphoses Edited by LAUREL FULKERSON and TIM STOVER THE UNIVE RSITY OF WI S CON SIN PRE SS The University of Wisconsin Press 1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059 Contents uwpress.wisc.edu 3 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden London WC2E SLU, United Kingdom eurospanbookstore.com Copyright © 2016 The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System Preface Allrights reserved. Except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical vii articles and reviews, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrievalsystem, transmitted in any format or by any means-digital, electronic, Introduction: Echoes of the Past 3 mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise-or conveyed via the LAUREL FULKERSON AND TIM STOVER Internetor a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. Rightsinquiries should be directed to rights@>uwpress.wisc.edu. 1 Nothing like the Sun: Repetition and Representation in Ovid's Phaethon Narrative 26 Printed in the United States of America ANDREW FELDHERR This book may be available in a digital edition. 2 Repeat after Me: The Loves ofVenus and Mars in Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ars amatoria 2 and Metamorphoses 4 47 BARBARA WElDEN BOYD Names: Fulkerson, Laurel, 1972- editor. 1 Stover, Tim, editor. Title: Repeat performances : Ovidian repetition and the Metamorphoses / 3 Ovid's Cycnus and Homer's Achilles Heel edited by Laurel Fulkerson and Tim Stover. PETER HESLIN Other titles: Wisconsin studies in classics. -

Manual of Mythology

^93 t.i CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY GIFT OF HENRY BEZIAT IN MEMORY OF ANDRE AND KATE BRADLEY BEZIAT 1944 Cornell University Library BL310 .M98 1893 and Rom No Manual of mythology. Greek « Cornell University S Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029075542 'f' liiiiiliilM^^ ^ M^ISTU^L MYTHOLOGY: GREEK AND ROMAN, NORSE, AND OLD GERMAN, HINDOO AND EGYPTIAN MYTHOLOGY. BY ALEXANDER S. MURRAY, DEPARTMENT OF GREEK AND ROMAN ANTIQUITIES, BRITISH MUSEUM- REPRINTED FROM THE SECOND REVISED LONDON EDITION. •WITH 45 PLATES ON TINTED PAPER, REPRESENTING MORE THAN 90 MYTHOLOGICAL SUBJECTS. NEW YORK: CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS, 1893. ; PUBLISHERS' NOTE. Murray's Manual of Mythology has been known to the American public thus far only through the English edition. As originally published, the work was deficient in its account of the Eastern and Northern Mythology; but with these imperfections it secured a sale in this country which proved that it more nearly supplied the want which had long been felt of a compact hand-book in this study than did any other similar work. The preface to the second English edition indicates the important additions to, and changes which have been made in, the original work. Chapters upon the North- ern and Eastern Mythology have been supplied ; the descrip- tions of many of the Greek deities have been re-written accounts of the most memorable works of art, in which each deity is or was represented, have been added ; and a number iii IV PUBLISHERS NOTE. -

Surviving Antigone: Anouilh, Adaptation, and the Archive

SURVIVING ANTIGONE: ANOUILH, ADAPTATION AND THE ARCHIVE Katelyn J. Buis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2014 Committee: Cynthia Baron, Advisor Jonathan Chambers ii ABSTRACT Dr. Cynthia Baron, Advisor The myth of Antigone has been established as a preeminent one in political and philosophical debate. One incarnation of the myth is of particular interest here. Jean Anouilh’s Antigone opened in Paris, 1944. A political and then philosophical debate immediately arose in response to the show. Anouilh’s Antigone remains a well-known play, yet few people know about its controversial history or the significance of its translation into English immediately after the war. It is this history and adaptation of Anouilh’s contested Antigone that defines my inquiry. I intend to reopen interpretive discourse about this play by exploring its origins, its journey, and the archival limitations and motivations controlling its legacy and reception to this day. By creating a space in which multiple readings of this play can exist, I consider adaptation studies and archival theory and practice in the form of theatre history, with a view to dismantle some of the misconceptions this play has experienced for over sixty years. This is an investigation into the survival of Anouilh’s Antigone since its premiere in 1944. I begin with a brief overview of the original performance of Jean Anouilh’s Antigone and the significant political controversy it caused. The second chapter centers on the changing reception of Anouilh’s Antigone beginning with the liberation of Paris to its premiere on the Broadway stage the following year. -

Llt 121 Classical Mythology Lecture 32 Good Morning

LLT 121 CLASSICAL MYTHOLOGY LECTURE 32 GOOD MORNING AND WELCOME TO LLT 121 CLASSICAL MYTHOLOGY IN WHICH WE RESUME OUR ADVENTURES IN THE CITY OF THEBES. THE CITY THAT THE GODS SEEM TO LOVE TO HATE. THE ORIGINAL FOUNDER TURNS INTO A SNAKE. WE'VE GOT THAT AT THEBES. A YOUNG MAN IS TURNED INTO A STAG FOR SEEING ARTEMIS BATHING IN THE NUDE. YES, WE HAVE THAT AT THEBES. THE SON KILLS THE FATHER. WE HAVE GOT THAT. WE DO THAT AT THEBES. THE SON MARRIES MOTHER. WE DO THAT TOO. BROTHER KILLS BROTHER, YEP. IF IT'S BAD AND IT HAPPENED IN ANCIENT GREEK MYTHOLOGY YOU CAN BET IT HAPPENED AT ANCIENT THEBES. I'VE ALREADY TOLD YOU WHY THAT IS. IT HAPPENS TO BE RIGHT NEXT DOOR TO ATHENS. WHERE I WANT TO START TODAY IS WITH ONE OF THE MOST FAMOUS CHARACTERS IN ALL WESTERN CIVILIZATION, ONE OF THE MOST COMPLEX PEOPLE YOU'LL EVER WANT TO MEET. THIS GUY IS BY THE NAME OF OEDIPUS. OEDIPUS STARTS OFF AS A LITTLE BABY. HE IS A CUTE LITTLE BABY. HE USED TO BE A LITTLE BOY. THEN HE WINDS UP AS THIS SAD, MULING, PUKING, UNHAPPY MAN WHO HAS POKED HIS OWN EYES OUT WITH A BROOCH. THIS IS THE GORE DRIPPING OUT OF HIS EYES AND ALL OF THAT BECAUSE HE SUFFERS FROM CLASSICAL GREEK MYTHOLOGY'S WORST DOCUMENTED CASE OF ARTIMONTHONO. NOW I GET IT. I PAUSE FOR YOUR QUESTIONS UP TO THIS POINT. WHEN LAST WE LEFT OFF LAIUS HAD BECOME KING AFTER A LONG WAIT WITH SOME INTERESTING MATHEMATICS BEHIND IT IF YOU'LL RECALL. -

Statius; with an English Translation by J.H. Mozley

THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY EDITED BY T. E. PAGE, LiTT.D. E. CAPPS, PH.D., LL.D. W. H. D. ROUSE, litt.d. STATIUS II ^cfi STATIUS f WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY J. H. MOZLEY, M.A. SOMETIME SCHOLAR OF KING S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE USCTDEER IN CLASSICS AT EAST LONDON COLLEGE, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON IN TWO VOLUMES J.^ II THEBAID V-XII • ACHILLEID LONDON : WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD NEW YORK: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS MCMXXVIII ; Printed in Great Britain CONTENTS OF VOLUME II THEBAID BOOKS V-XII VOL. 11 THEBAIDOS LIBER V Pulsa sitis fluvio, populataque gurgitis altum^ agmina linquebant ripas amnemque minorem ; acrior et campum sonipes rapit et pedes arva implet ovans, rediere viris animique minaeque votaque, sanguineis mixtum ceu fontibus ignem 5 hausissent belli magnasque in proelia mentes. dispositi in turmas rursus legemque severi ordinis, ut cuique ante locus ductorque, monentur instaurare vias. tellus iam pulvere primo crescit, et armorum transmittunt fulgura silvae. 10 qualia trans pontum Phariis depvensa serenis rauca Paraetonio deeedunt agmina Nilo, quo^ fera cogit hiemps : illae clangore fugaei, umbra fretis arvisque, volant, sonat avius aether, iam Borean imbresque pati, iam nare solutis 15 amnibus et nudo iuvat aestivare sub Haemo. Hie rursus simili procerum vallante corona dux Talaionides, antiqua ut forte sub orno ^ altum P : alvum w (Z) mith alveum written over). ^ quo Vollmer : cum Pa,-. " i.e., cranes, cf. Virg. Aen. x. 264.. * The epithet is taken from a town named Paraetonium, on the Libyan coast west of the Delta. 2 THEBAID BOOK V Their thirst was quenched by the river, and the army haWng ravaged the water's depths was lea\"ing the banks and the diminished stream ; more briskly now the galloping steed scours the plain, and the infantrj' swarm exultant over the fields, inspired once more by courage and hope and warlike temper, as though from the blood-stained springs they had drunk the fire of battle and high resolution for the fray. -

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

Gate to Vergil

THE GATE TO VERGIL BY CLARENCE W. GLEASON, A.M. MASTER IN THE ROXBURY LATIN SCHOOL »'• * GINN & COMPANY BOSTON . NEW YORK • CHICAGO • LONDON COPYRIGHT, 1898, BY CLARENCE W. GLEASON ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 613.10 Wf)t gtftcngtttn jgregg GINN & COMPANY • PRO PRIETORS • BOSTON • U.S.A. Poeta fui e cantai di quel giusto Figliuol d' Anchise, che venne da Troja Poich^ '1 superbo Ilion fu combusto. "A poet was I, and I sang that just Son of Anchises, who came forth from Troy, After that Ilion the superb was burned." Inferno, I, 73-75 (Longfellow's translation). PREFACE. THE course of a pupil beginning the study of Latin is not a smooth one. He starts out bravely enough, with his beginner's book and easy Latin reader, but is no sooner comfortably under way than he finds himself upon the ragged reefs of the Gallic War or, perhaps, stranded on the uncertain shoals of Nepos. If by careful steering he gets safely past these dangers he is immediately confronted by new obstacles which threaten him in the form of Latin verse. The sky grows dark, difficulties gather on all sides ; eripiunt subito nubes caelumque diemque. Sometimes he loses heart and drops the helm or, in spite of all his efforts, drifts back and must begin his cruise anew. It is with a view to remove some of the chief difficulties in the beginner's way that the present book has been pre pared. As the purpose of the Gate to Vergil is somewhat different from that of the Gate to Caesar and Gate to the Anabasis the work has been planned on slightly different lines. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles the Orphan-Hero in Italian Renaissance Epic a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfactio

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Orphan-Hero in Italian Renaissance Epic A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Italian by Sarah Sixmith Vogdes Cantor 2020 © Copyright by Sarah Sixmith Vogdes Cantor 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Orphan-Hero in Italian Renaissance Epic by Sarah Sixmith Vogdes Cantor Doctor of Philosophy in Italian University of California, Los Angeles, 2020 Professor Andrea Moudarres, Chair “The Orphan-Hero in Italian Renaissance Epic” investigates a commonplace present in epic poetry from antiquity to the Renaissance: the orphan-hero, a protagonist who grows up without the guidance of biological parents. The study traces this figure from its origins to the early modern period, beginning with classical epic in the introduction and focusing on 16th- and early 17th- century Italian poems in the body of the dissertation, namely Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando furioso (1532), Torquato Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata (1581), Tullia d’Aragona’s Il Meschino (1560), Moderata Fonte’s Floridoro (1581), Margherita Sarrocchi’s Scanderbeide (1623), and LucreZia Marinella’s L’Enrico (1635). Through analysis of these works, I address the following critical questions: 1) What links orphanhood and heroism? 2) Why might poets deem this tradition worthy of continuation? 3) Do modifications to the orphan-hero by different Renaissance authors reveal or emphasiZe shifts in thinking during the period? In particular, to what extent do the female authors fashion their orphan-heroes to fit an early modern feminist purpose? ii I propose that the vulnerability inherent in the parentless state is significant to the subsequent development of heroic qualities in Renaissance epic heroes. -

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary ILDENHARD INGO GILDENHARD AND JOHN HENDERSON A dead boy (Pallas) and the death of a girl (Camilla) loom over the opening and the closing part of the eleventh book of the Aeneid. Following the savage slaughter in Aeneid 10, the AND book opens in a mournful mood as the warring parti es revisit yesterday’s killing fi elds to att end to their dead. One casualty in parti cular commands att enti on: Aeneas’ protégé H Pallas, killed and despoiled by Turnus in the previous book. His death plunges his father ENDERSON Evander and his surrogate father Aeneas into heart-rending despair – and helps set up the foundati onal act of sacrifi cial brutality that caps the poem, when Aeneas seeks to avenge Pallas by slaying Turnus in wrathful fury. Turnus’ departure from the living is prefi gured by that of his ally Camilla, a maiden schooled in the marti al arts, who sets the mold for warrior princesses such as Xena and Wonder Woman. In the fi nal third of Aeneid 11, she wreaks havoc not just on the batt lefi eld but on gender stereotypes and the conventi ons of the epic genre, before she too succumbs to a premature death. In the porti ons of the book selected for discussion here, Virgil off ers some of his most emoti ve (and disturbing) meditati ons on the tragic nature of human existence – but also knows how to lighten the mood with a bit of drag. -

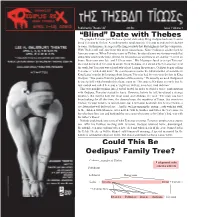

“Blind” Date with Thebes Could This Be Oedipus' Family Tree?

Published by Theatre ϋΔF 430 BC Issue 1 Volume 1 “Blind” Date with Thebes The prophet Teiresias paid Thebes a special visit today. King Oedipus had sent Creon to bring Teiresias to Thebes. According to the royal sources, Teiresias as extremely reluctant to come. Furthermore, he angered the king so much that His Highness lost his composure. With Thebes still suffering from this mysterious plague, King Oedipus is asking for help from any sources. When Teiresias came to Thebes, he uttered some mysterious words that apparently angered the king. At fi rst, he refused to say anything at all, stating: “Let me go home. Bear your own fate, and I’ll bear mine.” His Majesty refused to accept Teiresias’ plea and demanded Teiresias to speak. King Oedipus even pleaded to Teiresias to reveal the truth, but Teiresias was relentlessly silent. Losing his patience, Oedipus began calling Teiresias a “wicked old man.” He even began accusing the blind prophet of assisting in King Laius’ murder by keeping silent. In turn, Teiresias had the nerves to declare to King Oedipus: “You yourself are the pollution of this country.” He actually accused Oedipus of being the killer who brought this plague upon us. This angered Oedipus so much that he lost control and called Teiresias a “sightless, witless, senseless, mad old man.” This was quickly turning into a verbal brawl. In order to avoid a worse confrontation with Oedipus, Teiresias started to leave. However, before he left, he uttered a strange prophecy that baffl ed both the royal court and Oedipus. He said: “The man you have been looking for all this time, the damned man, the murderer of Laius, that man is in Thebes. -

Reading Jane Austen Through an Epic Lens: Pride and Prejudice and Emma

Reading Jane Austen through an Epic Lens: Pride and Prejudice and Emma (The Pursuit of Kleos in a Feminine Sphere) Honors Research Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for graduation “with Honors Research Distinction in Classics and English” in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Patricia Ryan The Ohio State University November 2012 Project Advisors: Professor Aman Garcha, Department of English Professor Anna McCullough, Department of Classics Ryan 2 Introduction to the Epic Hero When beginning a discussion on heroism, it is first necessary to define what it is to be a hero. A hero is someone exemplary, who excels above the rest of his or her peers in courage, virtue, character, and honor. The hero’s life is based on the achievement of a goal—the culmination of all heroic efforts. This goal-oriented life is best evidenced in the heroes of epic. In epic, the goal which all heroes strive for is the achievement of kleos. This Greek term, kleos, can be defined simply as “glory,” yet it means so much more to the epic hero. Kleos is everlasting glory or “the fame beyond even death that accrues to a hero because of his heroic feats” (Toohey 6). For the epic hero, the only way to gain kleos is by fighting—and most likely dying—in battle. Homer’s Odysseus (Odyssey) and Achilles (Iliad) epitomize the epic hero. These warriors, throughout their individual epic stories, undergo a journey in the pursuit of kleos, transforming themselves into the foremost Greeks both in battle and intelligence. -

Dr. Turhan Yörükân | Yunan Mitolojisinde Aşk

Dr. Turhan Yörükân | Yunan Mitolojisinde Aşk TÜRKİYE İŞ BANKASI Kültür Yayınları Dr. Turhan Yörükân 29 Aralık 1927'de İstanbul'da doğdu. Lise öğrenimini Latince eğitim veren çeşitli okullarda tamamladı. Dil ve Tarih Coğrafya Fakültesi Felsefe Bölümü'nü bitirdi; sonraları aynı fakültede psikoloji ve pedagoji -slstanı olarak görev yaptı. Gençliğinden başlayarak klasik filolojiyle İlgilenen Dr Yörükân Yunan mitosuna, felsefesine ve bilimine olan merakını hep canlı tuttu. Çeşitli bilimsel dergilerde makaleleri yayım lanan Dr. Yörükân yazar ve editör olarak otuzun üzerinde kitap yayımladı. Dr. Yörükân halen Ankara'da yaşıyor, çalışmalarını sürdürüyor. T Ü R K İY E İŞ B A N K A S I Kültür Yayınları Genel Yayın: 457 Edebiyat Dizisi: 115 Datça / Knidos’daki Aphrodite Euploia tapınağında yer alan Aphrodite heykeli için, Gaius Plinius Secundus (İ.S. 23- 79), yazdığı tabiî ilimler ansiklopedisinde (Naturalis Historia, 36, 20), “Praksiteles, bu eseriyle, mermer işleyen bir sanatçı olarak, kendisini bile aşmıştır... Onun bu eseri, sadece kendi yaptığı eserler içerisinde değil, bütün dünyadaki eserler içeri sinde en üstün olanı idi. Birçok kimse, denizler aşarak onu Knidos’ta görmeye geliyordu", diyor. Samsatlı (Samosatalı) Lukianos (İ.S. 120-200), Aşklar (13-14) adlı eserinde, “Bahçedeki bitkilerden yeterince haz duyduktan sonra, tapmağa girdik. Tanrıçanın Paros merme rinden yapılmış olağanüstü güzellikteki heykeli, tapmağın or tasında duruyordu... Vücudunun bütün güzelliği, herhangi bir örtü ile gizlenmiş değildi. Sadece bir eliyle, iffetini korumak istercesine önünü kapatıyordu. Sanatçının sergilediği üstün lük, taşın katı ve inatçı tabiatını kırmış, onu, her uzvun şekli ne uyum sağlamak zorunda bırakmıştı", diyor. Praksiteles’in yapmış olduğu Aphrodite heykelinin sikke ler üzerine darp edilmiş görüntüsü, aradan asırlar geçmiş ol masına rağmen, Roma Dönemi’nde etkisini sürdürmeye de vam etmiştir.