Induced Altruism in the Maintenance of Institutionalized Celibacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

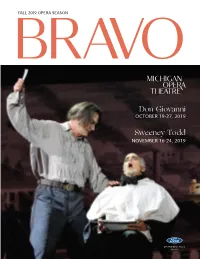

Don Giovanni Sweeney Todd

FALL 2019 OPERA SEASON B R AVO Don Giovanni OCTOBER 19-27, 2019 Sweeney Todd NOVEMBER 16-24, 2019 2019 Fall Opera Season Sponsor e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. Choose one from each course: FIRST COURSE Caesar Side Salad Chef’s Soup of the Day e Whitney Duet MAIN COURSE Grilled Lamb Chops Lake Superior White sh Pan Roasted “Brick” Chicken Sautéed Gnocchi View current menus DESSERT and reserve online at Chocolate Mousse or www.thewhitney.com Mixed Berry Sorbet with Fresh Berries or call 313-832-5700 $39.95 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. -

SEX (Education)

A Guide to Eective Programming for Muslim Youth LET’S TALK ABOUT SEX (education) A Resource Developed by the HEART Peers Program i A Guide to Sexual Health Education for Muslim Youth AT THE heart of the CENTRAL TO ALL MATTER WORKSHOPS WAS THE HEART Women & Girls seeks to promote the reproductive FOLLOWING QUESTION: health and mental well-being of faith-based communities through culturally-sensitive health education. How can we convey information about sexual Acknowledgments About the Project and reproductive health This toolkit is the culmination of three years of research The inaugural peer health education program, HEART and fieldwork led by HEART Women & Girls, an Peers, brought together eight dynamic college-aged to American Muslim organization committed to giving Muslim women and Muslim women from Loyola University, the University girls a safe platform to discuss sensitive topics such as of Chicago, and the University of Wisconsin–Madison women and girls in a body image, reproductive health, and self-esteem. The for a twelve-session training on sexual and reproductive final toolkit was prepared by HEART’s Executive Director health, with a special focus on sexual violence. Our eight manner that is mindful Nadiah Mohajir, with significant contributions from peer educator trainees comprised a diverse group with of religious and cultural Ayesha Akhtar, HEART co-founder & former Policy and respect to ethnicity, religious upbringing and practice, Research Director, and eight dynamic Muslim college- and professional training. Yet they all came together values and attitudes aged women trained as sexual health peer educators. for one purpose: to learn how to serve as resources for We extend special thanks to each of our eight educators, their Muslim peers regarding sexual and reproductive and also advocates the Yasmeen Shaban, Sarah Hasan, Aayah Fatayerji, Hadia health. -

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries Atlas of Whether used as a scholarly introduction into Eastern Christian monasticism or researcher’s directory or a travel guide, Alexei Krindatch brings together a fascinating collection of articles, facts, and statistics to comprehensively describe Orthodox Christian Monasteries in the United States. The careful examina- Atlas of American Orthodox tion of the key features of Orthodox monasteries provides solid academic frame for this book. With enticing verbal and photographic renderings, twenty-three Orthodox monastic communities scattered throughout the United States are brought to life for the reader. This is an essential book for anyone seeking to sample, explore or just better understand Orthodox Christian monastic life. Christian Monasteries Scott Thumma, Ph.D. Director Hartford Institute for Religion Research A truly delightful insight into Orthodox monasticism in the United States. The chapters on the history and tradition of Orthodox monasticism are carefully written to provide the reader with a solid theological understanding. They are then followed by a very human and personal description of the individual US Orthodox monasteries. A good resource for scholars, but also an excellent ‘tour guide’ for those seeking a more personal and intimate experience of monasticism. Thomas Gaunt, S.J., Ph.D. Executive Director Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) This is a fascinating and comprehensive guide to a small but important sector of American religious life. Whether you want to know about the history and theology of Orthodox monasticism or you just want to know what to expect if you visit, the stories, maps, and directories here are invaluable. -

Catholic Charities Centennial Prayer

Sooner Catholic Serving the People of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City Volume 37, Number 17 * September 11, 2011 Catholic Charities Centennial Prayer O God of the ages, With every sunrise, You gift us with work for our hands. With every sunset, You grant us rest for our hearts. May the light of each new day Give us faith in things unseen, Hope for victories yet unrealized, Charity for those who struggle. May the dusk of each night Bring us dreams of a better world, Visions of our cause triumphant, Love for the sacrifices asked of us. Grant your Church yet another century of service, Or time enough to build your Kingdom. This we ask in the name of Jesus, Our Lord. Amen and Amen. By Father James Goins Inside Anniversary trip to Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala 11-15 23 Painter rescues Our Lady 2 Sooner Catholic ● September 11, 2011 Sooner Catholic Catholic Charities Annual “Put out into the Most Reverend Appeal Celebrates One deep and Paul S. Coakley lower Archbishop of Oklahoma City Publisher Hundred Years of Service your nets A once in a lifetime opportunity We do not provide these services for a Ray Dyer is rare indeed! Even rarer is an because those we serve may happen catch.” event that comes around only every to be Catholic (many are not), but Archbishop Editor Luke 5:4 hundred years. Next weekend, we because we are Catholic. Caring for Coakley begin just such an observance. The Christ in his distressing disguise Cara Koenig annual Catholic Charities Appeal, of poverty is not an option for housing for families and the elderly, Photographer/ which will be held next weekend in Catholics, but a responsibility. -

Asexuality 101

BY THE NUMBERS Asexual people (or aces) experience little or no 28% sexual attraction. While most asexual people desire emotionally intimate relationships, they are not drawn to sex as a way to express that intimacy. of the community is 18 or younger ASEXUALITY ISN’T ACES MIGHT 32% Abstinence because of Want friendship, a bad relationship understanding, and Abstinence because of empathy religious reasons Fall in love of the community are between 19 and 21 Celibacy Experience arousal and Sexual repression, orgasm aversion, or Masturbate 19% dysfunction Have sex Loss of libido due to Not have sex age or circumstance Be of any gender, age, Fear of intimacy or background of the community are currently Inability to find a Have a spouse and/or in high school partner children 40% of the community are in college Aromantic – people who experience little or no romantic 20% attraction and are content with close friendships and other non-romantic relationships. Demisexual – people who only experience sexual attraction of the community identify as once they form a strong emotional connection with the person. transgender or are questioning Grey-A – people who identify somewhere between sexual and their gender identity asexual on the sexuality spectrum. 41% Queerplatonic – One type of non-romantic relationship where there is an intense emotional connection going beyond what is traditionally thought of as friendship. Romantic orientations – Aces commonly use hetero-, homo-, of the community identify as part of the LGBT community bi-, and pan- in front of the word romantic to describe who they experience romantic attraction to. Source: Asexy Community Census http://www.tinyurl.com/AsexyCensusResults Asexual Awareness Week Community Engagement Series – Trevor Project | Last Updated April 2012 ACE SPECIFIC Feeling e mpty, isolated, Some aces voice a fear of ISSUES and/or alone. -

7Th Grade 3.06 Define Abstinence As Voluntarily Refraining from Intimate

North Carolina Comprehensive School Health Training Center 3/07 C. 7th grade 3.06 Define abstinence as voluntarily refraining from intimate sexual contact that could result in unintended pregnancy or disease and analyze the benefits of abstinence from sexual until marriage. 7th grade 3.08 Analyze the effectiveness and failure rates of condoms as a means of preventing sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDS. 8th grade 3.08 Compare and contrast methods of contraception, their effectiveness and failure rates, and the risks associated with different methods of contraception, as a means of preventing sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDS. Materials Needed: Appendix 1 – Conception Quiz/STD Quiz – Teacher’s Key desk bells Appendix 2 – transparency of quotes about risk taking Appendix 3 – transparency of Effectiveness Rates for Contraceptive Methods Appendix 4 – background information on condom efficacy Appendix 5 – signs and cards for Contraceptive Effectiveness (cut apart) Appendix 6 – copies of What Would You Say? Review: Ask eight students to come to the front of the room and form two teams of four. They are to line up so they can ring in to answer questions using the Conception Quiz – Teacher’s Key for Appendix 1. Assign another student to determine who rings in first and explain they cannot ring in until they have heard the entire question. Each student will answer a question, go to the end of the line, and then have a second turn answering a question. If the question can be answered “yes” or “no,” they are to explain “why” or “why not.” Ask another eight students to come to the front and repeat the activity using the STD Quiz – Teacher’s Key. -

Provincial Reflection

VOL.48, NO.2 MAY 2017 Missionary Association of Mary Immaculate Provincial Reflection I am writing this on a 6 hour stopover with two remarkable Missionaries. One at the Hong Kong International Airport was a Spanish sister, Sister Rosario who, after having the privilege of spending after almost 40 years in northern India, a week and a half in the Philippines and and other places beforehand, came to then almost two weeks in Hong Kong/ Guangzhou at the age of 74 years, and China. I say a privilege because I have after 12 years there is going strong, with spent time with Oblates from the a passion for the people and the Lord Chinese. They continued, that although Asia/Oceania region and have visited which is infectious. The other missionary they appreciated the generosity and some of the inspiring places of their is Fr David Ullrich OMI who has spent the charity of so many, they were missionary outreach. almost 40 years in the Missions – Japan, concerned that perhaps the gifts the Hispanic Community in the USA and which came from wonderful people, The Oblates, whether in Cotabato, Manila, Mexico and now, 11 in China. They did did not meet the actual needs of the Hong Kong, Beijing or Guangzhou face not want me to mention their names people. They made mention that the many challenges (and rewards) that or their story. It needs to be told and needs of the people were not always we in the first world do not experience I will seek forgiveness when I next see in response to crises, such as the as they do. -

The Franciscan Crown in 1422, an Apparition of the Blessed Virgin Mary Took Place in Assisi, to a Certain 7

History of the Franciscan Crown In 1422, an apparition of the Blessed Virgin Mary took place in Assisi, to a certain 7. Assumption & Coronation Franciscan novice, named James. As a child he had a custom of daily offering a crown Vision of Friar James of roses to our Blessed Mother. When he entered the Friar Minor, he became distressed that he would no longer be able to offer this type of gift. He considered leaving when our Lady appeared to him to give him comfort and showed him another daily offering he could do. Our Lady said : “In place of the flowers that soon wither and cannot always be found, you can weave for me a crown from the flowers of your prayers … Recite one Our Father and ten How to Pray the Franciscan Crown Hail Marys while recalling the Seven Joys I experienced.” Begin with the Sign of the Cross (no creed Friar James began at once to pray as directed. or opening prayers) Meanwhile, the novice master entered and 1. Announce the first Mystery, then pray saw an angel weaving a wreath of roses and one Our Father (no Glory Be). after every tenth rose, the angel, inserted a THE 2. Pray Ten Hail Mary’s while meditating golden lily. When the wreath was finished, FRANCISCAN on the Mystery. he placed it on Friar James’ head. The novice 3. Announce second Mystery and repeat master commanded the youth to tell him CROWN one and two through the seven decades. what he had been doing; and Friar James 4. -

Peoples in the Brazilian Amazonia Indian Lands

Brazilian Demographic Censuses and the “Indians”: difficulties in identifying and counting. Marta Maria Azevedo Researcher for the Instituto Socioambiental – ISA; and visiting researcher of the Núcleo de Estudos em População – NEPO / of the University of Campinas – UNICAMP PEOPLES IN THE BRAZILIAN AMAZONIA INDIAN LANDS source: Programa Brasil Socioambiental - ISA At the present moment there are in Brazil 184 native language- UF* POVO POP.** ANO*** LÍNG./TRON.**** OUTROS NOMES***** Case studies made by anthropologists register the vital events of a RO Aikanã 175 1995 Aikanã Aikaná, Massaká, Tubarão RO Ajuru 38 1990 Tupari speaking peoples and around 30 who identify themselves as “Indians”, RO Akunsu 7 1998 ? Akunt'su certain population during a large time period, which allows us to make RO Amondawa 80 2000 Tupi-Gurarani RO Arara 184 2000 Ramarama Karo even though they are Portuguese speaking. Two-hundred and sixteen RO Arikapu 2 1999 Jaboti Aricapu a few analyses about their populational dynamics. Such is the case, for RO Arikem ? ? Arikem Ariken peoples live in ‘Indian Territories’, either demarcated or in the RO Aruá 6 1997 Tupi-Mondé instance, of the work about the Araweté, made by Eduardo Viveiros de RO Cassupá ? ? Português RO/MT Cinta Larga 643 1993 Tupi-Mondé Matétamãe process of demarcation, and also in urban areas in the different RO Columbiara ? ? ? Corumbiara Castro. In his book (Araweté: o povo do Ipixuna – CEDI, 1992) there is an RO Gavião 436 2000 Tupi-Mondé Digüt RO Jaboti 67 1990 Jaboti regions of Brazil. The lands of some 30 groups extend across national RO Kanoe 84 1997 Kanoe Canoe appendix with the populational data registered by others, since the first RO Karipuna 20 2000 Tupi-Gurarani Caripuna RO Karitiana 360 2000 Arikem Caritiana burder, for ex.: 8,500 Ticuna live in Peru and Colombia while 32,000 RO Kwazá 25 1998 Língua isolada Coaiá, Koaiá contact with this people in 1976. -

Sex with Guilt

Review Sex With Guilt James A. Brundage. Law, Sex, and Christian Society in Medieval Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987. Pp. xxiv, 674. $45.00. Paul Freedman Medieval law was an accretion of traditions from several sources. This is well known, for example, with regard to the historical development of English Common Law. Continental and church law of the Middle Ages was built on a foundation of Roman or Roman-inspired codes and prac- tices and so tended to emphasize statute and authoritative executive state- ments more than did customary laws. In both its political government and legislation the medieval church was increasingly centralized. Nevertheless, even the church faced the task of reconciling diverse norms and precedents (Biblical, Patristic, Roman, Germanic) that reflected conflicting proce- dures and social expectations. One might expect medieval canon law relat- ing to sexual behavior to have been straightforward and unyielding, but this is not the case. Because of the interaction of ethical and textual tradi- tions, and the nature of medieval society (which was rather more exuber- ant than is commonly believed), the development of ecclesiastical regula- tion was slow and complex. The Middle Ages was hardly unique in attempting to control the mani- festations of sexual desire. All societies have both informal expectations and formal rules about sex and marriage. Where they differ, often radi- cally, is in marking off aspects of sexual and domestic relations considered private and thus left to individual conscience or preference from those sub- Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities, Vol. 1, Iss. 2 [1989], Art. 5 Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities [Vol. -

Holistic Approach to Mental Illnesses at the Toby of Ambohibao Madagascar Daniel A

Luther Seminary Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary Doctor of Ministry Theses Student Theses 2002 Holistic Approach to Mental Illnesses at the Toby of Ambohibao Madagascar Daniel A. Rakotojoelinandrasana Luther Seminary Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/dmin_theses Part of the Christianity Commons, Mental and Social Health Commons, and the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Rakotojoelinandrasana, Daniel A., "Holistic Approach to Mental Illnesses at the Toby of Ambohibao Madagascar" (2002). Doctor of Ministry Theses. 19. http://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/dmin_theses/19 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOLISTIC APPROACH TO MENTAL ILLNESSES AT THE TOBY OF AMBOHIBAO MADAGASCAR by DANIEL A. RAKOTOJOELINANDRASANA A Thesis Submitted to, the Faculty of Luther Seminary And The Minnesota Consortium of Seminary Faculties In Partial Fulfillments of The Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MINISTRY THESIS ADVISOR: RICHARD WALLA CE. SAINT PAUL, MINNESOTA 2002 LUTHER SEMINARY USRARY 22-75Como Aver:ue 1 ©2002 by Daniel Rakotojoelinandrasana All rights reserved 2 Thesis Project Committee Dr. Richard Wallace, Luther Seminary, Thesis Advisor Dr. Craig Moran, Luther Seminary, Reader Dr. J. Michael Byron, St. Paul Seminary, School of Divinity, Reader ABSTRACT The Church is to reclaim its teaching and praxis of the healing ministry at the example of Jesus Christ who preached, taught and healed. Healing is holistic, that is, caring for the whole person, physical, mental, social and spiritual. -

![Asadisa,Dāna Vatthu the Incomparable Giving [The Joy of Giving] (Dha 13.10/3:182-192) Translated & Annotated by Piya Tan ©2008](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8843/asadisa-d%C4%81na-vatthu-the-incomparable-giving-the-joy-of-giving-dha-13-10-3-182-192-translated-annotated-by-piya-tan-%C2%A92008-518843.webp)

Asadisa,Dāna Vatthu the Incomparable Giving [The Joy of Giving] (Dha 13.10/3:182-192) Translated & Annotated by Piya Tan ©2008

Dhammapad’aṭṭha,kathā vol 3 DhA 13.10 Asadisa,dāna Vatthu Asadisa,dāna Vatthu The Incomparable Giving [The joy of giving] (DhA 13.10/3:182-192) Translated & annotated by Piya Tan ©2008 1 Dhammapada Story: The incomparable gift While the Āditta Jātaka (J 424) tells the story of the past regarding the incomparable giving (asadi- sa,dāna),1 the Dhammapada Commentary on Dh 177 (DhA 13.10) has the story of the present—the Asadisa,dāna Vatthu—regarding the same incomparable giving made by the rajah Pasenadi to the Buddha himself. The Āditta Jātaka commentary refers to the Mahā Govinda Sutta (D 19) commentary for the full story (DA 2:652-655). ——— 2 The Incomparable Giving (DhA 13.10/3:182-192) “The miserly certainly do not…” (na ve kadariyā). This Dharma teaching was given by the Teacher while he was staying in the Jeta,vana, with reference to the incomparable giving (asadisa,dāna). [183] 2.1 PASENADI AND CITIZENS OFFER ALMS. At one time, the Teacher, with a retinue of 500 monks, having wandered about, entered Jeta,vana. The king went to the monastery, invited the Teacher, and on the following day, had an incidental alms-giving [alms-giving for guests] (āgantuka,dāna) prepared, and announced to the city, “Come and see my giving!” On the next day, the citizens came, saw the king’s alms-giving, and then invited the Buddha for an alms-giving on the following day, and sent word to the king, “Your majesty, please come and see our giving.” The king saw their alms-giving and thought, “They have made a greater giving than mine.