Inspiration and Inerrancy of the Bible: an Exegetical Interpretation of 1Tim 3,16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Must Satan Be Released? Indeed He Must Be: Toward a Biblical Understanding of Revelation 20:3 Gregory H

Volume 25, Number 1 • Spring 2014 Must Satan Be Released? Indeed He Must Be: Toward a Biblical Understanding of Revelation 20:3 Gregory H. Harris Regaining Our Focus: A Response to the Social Action Trend in Evangelical Missions Joel James and Brian Biedebach The Seed of Abraham: A Theological Analysis of Galatians 3 and Its Implications for Israel Michael Riccardi A Review of Five Views on Biblical Inerrancy Norman L. Geisler THE MASTER’S SEMINARY JOURNAL published by THE MASTER’S SEMINARY John MacArthur, President Richard L. Mayhue, Executive Vice-President and Dean Edited for the Faculty: William D. Barrick John MacArthur Irvin A. Busenitz Richard L. Mayhue Nathan A. Busenitz Alex D. Montoya Keith H. Essex James Mook F. David Farnell Bryan J. Murphy Paul W. Felix Kelly T. Osborne Michael A. Grisanti Dennis M. Swanson Gregory H. Harris Michael J. Vlach Matthew W. Waymeyer by Richard L. Mayhue, Editor Michael J. Vlach, Executive Editor Dennis M. Swanson, Book Review Editor Garry D. Knussman, Editorial Consultant The views represented herein are not necessarily endorsed by The Master’s Seminary, its administration, or its faculty. The Master’s Seminary Journal (MSJ) is is published semiannually each spring and fall. Beginning with the May 2013 issue, MSJ is distributed electronically for free. Requests to MSJ and email address changes should be addressed to [email protected]. Articles, general correspondence, and policy questions should be directed to Dr. Michael J. Vlach. Book reviews should be sent to Dr. Dennis M. Swanson. The Master’s Seminary Journal 13248 Roscoe Blvd., Sun Valley, CA 91352 The Master’s Seminary Journal is indexed in Elenchus Bibliographicus Biblicus of Biblica; Christian Periodical Index; and Guide to Social Science & Religion in Periodical Literature. -

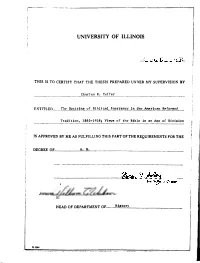

University of Illinois

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THIS tS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Charles K. Telfer ENTITLED......... The Doctrine oM bHcal.. T nerrancy. i nt ^ R? foiled Tradition, 1865-19185 Views of the Bible in an Arc of Division IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF............................. ............................................................................................................................ HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF. OII64 THE DOCTRINE OF BIBLICAL INERRANCY IN THE AMERICAN REFORMED TRADITION, 1865-1918 VIEWS OF THE BIBLE IN AN AGE OF DIVISION BY CHARLES K. TELFER THESIS for the DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS IN LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES College of Liberal Arts and Sciences University of Illinois Urbana, Illinois 1985 I. Introduction There is an increasing unanimity of opinion among historians of America’s cultural, intellectual, and religious history that the years between 1865 and 1935 form a distinct ’’epoch” or ’’period.” A number of important books published in recent years reflect this conception. Lefferts Loetscher in his masterly work on the Presbyterian Church entitled The Broadening Church (1954) deals with the years 1864 to 1936. In I960, George Marsden produced Fundamentalism and American Cultures The Shaping of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism, 1870-1925. In The Divided Mind of Protestant Amerlcat 1880-1930 (1982), Ferenc Szasz view9 these years as a distinct period in this country’s religious history.1 The years 1865 to 1935 may be typified as an ”age of division” for the American Protestant church. The church as a whole and particular denominations were rift by conflicts over important matters into ’’liberal” and ’’conservative” camps. Of course, the most well-known battles between ’’liberals” and ’’conservatives” took place in the twenties during the Modernist-Fundamentalist Controversy. -

A Study of the Idea of the VERBAL INSPIRATION OP the SCRIPTURES

A Study of the Idea of THE VERBAL INSPIRATION OP THE SCRIPTURES with special reference to. the Reformers and Post-Reformation Thinkers of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Divinity of the University of Edinburgh in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Ph.D. degree. Allan Andrew Zaun, B.A., B.D- May 15,1937 PREFACE. At the outset of this study it will be well to define terms. By "verbal Inspiration11 we mean the theory which main tains that in the process of recording the Scriptures, the Holy Spirit Himself selected the very words which the writers used. In the same sense that Milton is the author of Paradise Lost, the Holy Spirit is held to be the author of Scripture. Whether communicated by suggestion or actual dictation, the words of the text are the exact words, and no other, which God wished to have employed. The form, as well as the content, is liter ally given by Gk>d. This, briefly, is the verbal theory. We recognize the intimate, but not absolutely inseparable, con nection between thought and language. To the extent that words can be an adequate expression of the thought, Inspiration is verbal; however, the classic formulation of the doctrine, in its insistence upon dictation and verbal inerrancy, introduced mechanical features with which many scholars today cannot find themselves in full agreement. In the Reformation and post-Reformation periods we are confining our study principally to the dogmaticians of Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands; nq attempt has been made to trace the development of the doctrine in England and Scotland, which, however, were profoundly influenced by the Genevan Reformation. -

INSTITUTES of the CHRISTIAN RELIGION VOL. 1 Translated by Ford Lewis Battles

THE AGES DIGITAL LIBRARY THEOLOGY INSTITUTES OF THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION VOL. 1 Translated by Ford Lewis Battles Used by permission from The Westminster Press All Rights Reserved B o o k s F o r Th e A g e s AGES Software • Albany, OR USA Version 1.0 © 1998 2 JOHN CALVIN: INSTITUTES OF THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION EDITED BY JOHN T. MCNEILL Auburn Professor Emeritus of Church History Union Theological Seminary New York TRANSLATED AND INDEXED BY FORD LEWIS BATTLES Philip Schaff Professor of Church History The Hartford Theological Seminary Hartford, Connecticut in collaboration with the editor and a committee of advisers Philadelphia 3 GENERAL EDITORS’ PREFACE The Christian Church possesses in its literature an abundant and incomparable treasure. But it is an inheritance that must be reclaimed by each generation. THE LIBRARY OF CHRISTIAN CLASSICS is designed to present in the English language, and in twenty-six volumes of convenient size, a selection of the most indispensable Christian treatises written prior to the end of the sixteenth century. The practice of giving circulation to writings selected for superior worth or special interest was adopted at the beginning of Christian history. The canonical Scriptures were themselves a selection from a much wider literature. In the patristic era there began to appear a class of works of compilation (often designed for ready reference in controversy) of the opinions of well-reputed predecessors, and in the Middle Ages many such works were produced. These medieval anthologies actually preserve some noteworthy materials from works otherwise lost. In modern times, with the increasing inability even of those trained in universities and theological colleges to read Latin and Greek texts with ease and familiarity, the translation of selected portions of earlier Christian literature into modern languages has become more necessary than ever; while the wide range of distinguished books written in vernaculars such as English makes selection there also needful. -

The Fitness of Scripture: Richard Chenevix Trench and Victorian Doctrines of Scripture

The Fitness of Scripture: Richard Chenevix Trench and Victorian Doctrines of Scripture by Cole William Hartin A Doctoral Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Wycliffe College and the Graduate Centre for Theological Studies of the Toronto School of Theology. In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theological Studies awarded by Wycliffe College and the University of Toronto. © Copyright by Cole William Hartin 2019 The Fitness of Scripture: Richard Chenevix Trench and Victorian Doctrines of Scripture Cole William Hartin Doctor of Philosophy in Theological Studies Wycliffe College and the University of Toronto 2019 Abstract This thesis outlines Archbishop Richard Chenevix Trench’s theology of Scripture, showing that he reads the Bible distinctively by situating him within the broader Victorian Church of England. Furthermore, it argues that because of the clarity with which Trench apprehends the character of Scripture and the interpretive implications of this, he offers a comprehensive paradigm from which one can articulate a coherent understanding of “the fitness of Holy Scripture for unfolding the spiritual life of men.” I examine Trench’s theology of Scripture by way of comparison with other prominent thinkers in the Church of England during his time. First, Charles Simeon’s devout but unidimensional interpretation, which aims to discover the full range of biblical teaching, is set beside Trench’s layered Christological reading of the text. The next chapter discusses Benjamin Jowett’s attempts to uncover the original meaning and context of each passage of Scripture. Trench’s doctrine of the Holy Spirit’s authorship juxtaposes with Jowett, opening room for a further future unfolding of the meaning inherent in Scripture. -

A History of Seventh-Day Adventist Views on Biblical and Prophetic Inspiration (1844-2000)

Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 10/1-2 (1999): 486Ð542. Article copyright © 2000 by Alberto R. Timm. A History of Seventh-day Adventist Views on Biblical and Prophetic Inspiration (1844Ð2000) Alberto R. Timm Director, Brazilian Ellen G. White Research Center Brazil Adventist UniversityÐCampus 2 Introduction Seventh-day Adventists form a modern eschatological movement born out of the study of the Holy Scriptures, with the specific mission of proclaiming the Word of God Òto every nation and tribe and tongue and peopleÓ (Rev 14:6, RSV). In many places around the world Seventh-day Adventists have actually been known as the Òpeople of the Book.Ó As a people Adventists have always heldÑand presently holdÑhigh respect for the authority of the Bible. However, at times in the denominationÕs history different views on the nature of the Bi- bleÕs inspiration have been discussed within its ranks. The present study provides a general chronological overview of those major trends and challenges that have impacted on the development of the Seventh-day Adventist understanding of inspiration between 1844 and 2000. An Òannotated bibliographyÓ type of approach is followed to provide an overall idea of the subject and to facilitate further investigations of a more thematic nature. The Adventist understanding of inspiration as related to both the Bible and the writings of Ellen White is considered for two evident reasons: (1) While their basic function differs, Adventists have generally assumed that both sets of writings were produced by the same modus operandi of inspiration, and (2) there is an organic overlapping of the views on each in the development of an understanding of the BibleÕs inspiration. -

Wesleyan Theological Journal

Wesleyan Theological Journal Volume 16, Number 1, Spring, 1981 Presidential Address: History and Hermeneutics: A Pannenbergian Perspective Laurence W. Wood 7 John Wesley’s Approach to Scripture in Historical Perspective R. Larry Shelton 23 The Devotional Use of Scripture in the Wesleyan Movement William Vermillion 51 A Wesleyan Interpretation of Romans 5 — 8 Jerry McCant 68 Charles Williams’ Concept of Imaging Applied to the “Song of Songs” Dennis Kinlaw 85 A Problem of Unfulfilled Prophecy in Ezekiel: The Destruction of Tyre David Thompson 93 Notes on the Exegesis of John Wesley’s Explanatory Notes upon the New Testament Timothy L. Smith 107 6 HISTORY AND HERMENEUTICS: A PANNENBERGIAN PERSPECTIVE by Laurence Wood What is the relation of history and hermeneutics? This has been a question of much debate in contemporary theology. It is well known that the theological giants of this century-Barth, Bultmann, and Tillich-believed that critical history raised serious problems for Christian faith. In order to protect the purity of faith from the onslaughts of critical history, revelation was identified exclusively with the Word of God. Not history but language was thus the primary locus of revelation. In this way the truth of faith could not be put at the mercy of the critical historian. In Bultmann‟s kerygmatic theology and Barth‟s theology of the Word of God, the primary locus of revelation was centered in the Word, thus putting revelation outside the possibility of critical inquiry. Though Barth added historical elements to his dogmatics, revelation itself did not come under the general category of verifiable truth. -

Copyright © 2019 Matthew Lee Lyon All Rights Reserved. the Southern

Copyright © 2019 Matthew Lee Lyon All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. JOHN R. RICE AND EVANGELISM: AN ESSENTIAL MARK OF INDEPENDENT BAPTIST FUNDAMENTALISM __________________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________________ by Matthew Lee Lyon May 2019 APPROVAL SHEET JOHN R. RICE AND EVANGELISM: AN ESSENTIAL MARK OF INDEPENDENT BAPTIST FUNDAMENTALISM Matthew Lee Lyon Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ Thomas J. Nettles (Chair) __________________________________________ John D. Wilsey __________________________________________ Shawn D. Wright Date______________________________ To Mom and Dad TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE.........................................................................................................................viii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................1 Biographical Overview.......................................................................................2 Thesis..................................................................................................................5 Personal Background..........................................................................................7 -

Has the Church Misread the Bible?

Foundations of Contemporary Interpretation MoisCs Silva, Series Editor Volume 1 HAS THE CHURCH MISREAD THE BIBLE? THE HISTORY OF INTERPRETATION IN THE LIGHT OF CURRENT ISSUES ZondervanPublishingHouse Grand Rapids, Michigan A Division of HarperCollinsPublishers Dedicated to the Memory of My Revered Teacher EDWARD J. YOUNG erudite scholar and humble believer, whose hevmeneutics rejected no con.ict between devotion to the Scriptures H AS THE CHURCH M ISREAD THE BIBLE? and regard for the intellect copyright Q 1987 by MoisCs Silva Requests for information should be addressed to: Zondervan Publishing House Grand Rapids, Michigan 49530 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Silva, MoisCs Has the church misread the Bible? (Foundations of contemporary interpretations ; v. 1) Bibliography: p. Includes indexes. 1. Bible--Hermeneutics. 2. Bible-Ctiticism, interpretation, etc.-History. I. Title. II. Series. BS476.S55 1987 220.6’01 87-14476 ISBN 0-310-75501-8-O All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise noted, are taken from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONLAL VERSION (North American Edition). Copyright Q 1973, 1978, 1984 by The International Bible Society. Used by per- mission of Zondervan Bible Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means-electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other-except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Edited by Craig No11 Designed by Louise Bauer P&ted in the United States ofAnte& 959697/DH/9876 CONTENTS Preface vi . The Role of Scholarship 89 Abbreviations Vlll The Whole Counsel of God 92 I. -

Is the Princeton View of Scripture an Enlightenment Innovation?

Is the Princeton View of Scripture an Enlightenment Innovation? Carl R. Trueman, Westminster Theological Seminary, PA. Before addressing the subject of the title of this paper, I would like to make a couple of comments about the nature and scope of the argument which I wish to present. First, this is not an exercise in systematic theology. I am not a systematician and have no desire to be one; rather, I am an historian, and thus that which I present here is an attempt at historical, rather than theological, analysis. My aim in this paper is thus comparatively modest: I will not argue that the Princetonian approach to scripture, articulated most fully and forcefully by B.B. Warfield is right or wrong; the case for, as the case against, needs to be made on exegetical and theological, not historical grounds. Rather, I will argue simply that there is little that is particularly innovative in the nineteenth century Princeton doctrine, and that the various aspects of the basic Protestant doctrine of scripture find antecedents in earlier points of church history. This is not to argue that the fully- fledged Princetonian doctrine can be found in mature form in earlier periods; but simply that its various elements can be found there. This should be sufficient to cause pause for thought among those who confidently dismiss it as rationalism. 1 Second, I am acutely aware of the classic historian’s dilemma, of demanding that texts written in one time and context should provide answers to questions raised in another time and another place. -

Calvin's Doctrine of the Knowledge of God1

Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield CALVIN'S DOCTRINE OF THE KNOWLEDGE OF GOD1 The first chapters of Calvin's "Institutes" are taken up with a comprehensive exposition of the sources and guarantee of the knowledge of God and divine things (Book I. chs. i.-ix.). A systematic treatise on the knowledge of God must needs begin with such an exposition; and we require no account of the circumstance that Calvin's treatise begins with it, beyond the systematic character of his mind and the clearness and comprehensiveness of his view. This exposition therefore makes its appearance in the earliest edition of the "Institutes," which attempted "to give a summary of religion in all its parts," redacted in orderly sequence; that is to say, which was intended as a textbook in theology. This was the second edition, published in 1539, which was considered by Calvin to be the first which at all corresponded to its title. In this edition this exposition already stands practically complete. Large insertions were made into it subsequently, by which it was greatly enriched as a detailed exposition and validation of the sources of our knowledge of God; but no modifications were made in its fundamental teaching by these additions, and the ground plan of the exposition as laid down in 1539 was retained unaltered throughout the subsequent development of the treatise. We may observe in the controversies in which Calvin had been engaged between 1536 and 1539 a certain preparation for writing this comprehensive and admirably balanced statement, with its equal repudiation of Romish and Anabaptist error and its high note of assurance in the face of the scepticism of the average man of the world. -

1956, EC Blackman, Biblical Interpretation, London

© 1956, E.C. Blackman, Biblical Interpretation, London: Independent Press Ltd, The United Reformed Church to 63 nt'"" ~ c;~ ~ 0z BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION THE OLD DIFFICULTIES AND THE NEW OPPORTUNITY E. C. BLACKMAN LONDON INDEPENDENT PRESS LTD. MEMORIAL HALL, E.C.4 First published 1957 All rights reserved MADE AND PllINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY THE GARDEN CITY PRESS LIMITED I.ETCHWOII.TII, HEII.TFORDSHD!B CONTENTS Chapter Page PREFACE 7 I INTRODUCTORY 9 II THE MEANING OF REVELATION 23 III THE QUESTION OF AUTHORITY 41 IV THE DEVELOPMENT OF EXEGESIS 65 A. RABBINIC EXEGESIS 66 B. ALLEGORY-PHILO TO AUGUSTINE 76 c. MEDIEVAL EXEGESIS 108 D. THE REFORMATION AND AFTER 116 V MODERN CRITICISM 130 VI THE PRESENT TASK IN BIBLICAL EXPOSITION 159 INDEX BIBLE PASSAGES 207 GENERAL SUBJECT 209 MODERN AUTHORS 211 s PREFACE HE aim of this book is to serve 'the cause of true exposition. The three longer chapters IV-VI are more obviously related Tto that purpose than the others. Chapter IV is historical, and tries to give an impression of how Christian teachers and preachers through nineteen centuries have in fact expounded the Bible. Chapter VI is intended to be a climax in that it ventures to lay down canons of exegesis for the preacher today. It seemed advisable to preface these larger chapters with some discussion of issues about which it is essential for the preacher to have a right judgment: the significance of the Bible as Revelation, the authority of the Bible in the setting of the general problem of moral and spiritual authority, and the function and limits of historical criticism as applied to the Bible.