Calvin and Calvinism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Must Satan Be Released? Indeed He Must Be: Toward a Biblical Understanding of Revelation 20:3 Gregory H

Volume 25, Number 1 • Spring 2014 Must Satan Be Released? Indeed He Must Be: Toward a Biblical Understanding of Revelation 20:3 Gregory H. Harris Regaining Our Focus: A Response to the Social Action Trend in Evangelical Missions Joel James and Brian Biedebach The Seed of Abraham: A Theological Analysis of Galatians 3 and Its Implications for Israel Michael Riccardi A Review of Five Views on Biblical Inerrancy Norman L. Geisler THE MASTER’S SEMINARY JOURNAL published by THE MASTER’S SEMINARY John MacArthur, President Richard L. Mayhue, Executive Vice-President and Dean Edited for the Faculty: William D. Barrick John MacArthur Irvin A. Busenitz Richard L. Mayhue Nathan A. Busenitz Alex D. Montoya Keith H. Essex James Mook F. David Farnell Bryan J. Murphy Paul W. Felix Kelly T. Osborne Michael A. Grisanti Dennis M. Swanson Gregory H. Harris Michael J. Vlach Matthew W. Waymeyer by Richard L. Mayhue, Editor Michael J. Vlach, Executive Editor Dennis M. Swanson, Book Review Editor Garry D. Knussman, Editorial Consultant The views represented herein are not necessarily endorsed by The Master’s Seminary, its administration, or its faculty. The Master’s Seminary Journal (MSJ) is is published semiannually each spring and fall. Beginning with the May 2013 issue, MSJ is distributed electronically for free. Requests to MSJ and email address changes should be addressed to [email protected]. Articles, general correspondence, and policy questions should be directed to Dr. Michael J. Vlach. Book reviews should be sent to Dr. Dennis M. Swanson. The Master’s Seminary Journal 13248 Roscoe Blvd., Sun Valley, CA 91352 The Master’s Seminary Journal is indexed in Elenchus Bibliographicus Biblicus of Biblica; Christian Periodical Index; and Guide to Social Science & Religion in Periodical Literature. -

Reader's Guide

T H E H UMILITY T O R E A D I am one person in one place at one time. My experiences and perceptions are limited and Introducing the colored by the environment in which I live. ESV Study Bible Therefore, it would be profoundly arrogant of me to think that I can best grow in the knowl- 20,000 Notes edge of God through Scripture by myself. 40 Illustrations A Monergism Books Certainly the Holy Spirit is graciously given to 50 Articles all God’s children to enable us to comprehend and be conformed to the truths of the Bible. 200 Full-Color Maps READER’S GUIDE Nevertheless, one of the primary means of The ESV Study Bible for the Christian Life grace God uses in the process of our transfor- was created to help mation is the universal-historical community of people understand believers. Within that community, God gra- the Bible in a ciously provides leaders of few and leaders of deeper way—to understand the timeless many to equip the saints for the work of minis- truth of God’s Word as a powerful, com- try. pelling, life-changing reality. To accom- It is a humbling thing for me to read a book. plish this, the ESV Study Bible combines Most books take at least several hours of com- the best and most recent evangelical bined time to process, and I have to forsake Christian scholarship with the highly other distractions in order to focus and benefit regarded ESV Bible text. The result is the from what I am reading. -

The Two Resurrections

1 The Two Resurrections: John 5:19-29 and Revelation 20:4-6 By Aaron Orendorff The interpretive history of Revelation 20 is a virtual battleground for hermeneutical, theological and eschatological agendas.1 Due in part to the Icarian rise of dispensational theology in post-war years of the early 20th century, no other single passage of Scripture has received as much hotly contested evangelical attention as the first ten verses of this apocalyptic chapter. The various interpretive debates, even at a popular level, present a compelling argument in favor of postmodernism’s wholesale abandonment of recoverable meaning. Yet despite these stifling, nearly overwhelming discouragements, eschatology – the “systematic study of eventualities” as J. Oliver Buswell defines it2 – is far from a mere peripheral disciple in the world of Christian theology. On the contrary, as Anthony Hoekema has written, “Eschatology must not be thought of as something which is found only in, say, such Bible books as Daniel and Revelation, but as dominating and permeating the entire message of the Bible.”3 “From first to last,” Moltmann declared, “and not merely in the epilogue, Christianity is eschatology, is hope, forward looking and forward moving, and therefore also revolutionizing and transforming the present…It is the medium of the Christian faith…the key in which everything in it is set.”4 In light, therefore, of both the difficulties inherent and the necessities at stake, rather than trying to assess this embroiled chapter in its totality, particularly as it pertains to the all too often centralizing question regarding the millennium, my approach will be to address one issue – the nature of the two resurrections in v. -

Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform

6 RENAISSANCE HISTORY, ART AND CULTURE Cussen Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform of Politics Cultural the and III Paul Pope Bryan Cussen Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform 1534-1549 Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform Renaissance History, Art and Culture This series investigates the Renaissance as a complex intersection of political and cultural processes that radiated across Italian territories into wider worlds of influence, not only through Western Europe, but into the Middle East, parts of Asia and the Indian subcontinent. It will be alive to the best writing of a transnational and comparative nature and will cross canonical chronological divides of the Central Middle Ages, the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period. Renaissance History, Art and Culture intends to spark new ideas and encourage debate on the meanings, extent and influence of the Renaissance within the broader European world. It encourages engagement by scholars across disciplines – history, literature, art history, musicology, and possibly the social sciences – and focuses on ideas and collective mentalities as social, political, and cultural movements that shaped a changing world from ca 1250 to 1650. Series editors Christopher Celenza, Georgetown University, USA Samuel Cohn, Jr., University of Glasgow, UK Andrea Gamberini, University of Milan, Italy Geraldine Johnson, Christ Church, Oxford, UK Isabella Lazzarini, University of Molise, Italy Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform 1534-1549 Bryan Cussen Amsterdam University Press Cover image: Titian, Pope Paul III. Museo di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy / Bridgeman Images. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 252 0 e-isbn 978 90 4855 025 8 doi 10.5117/9789463722520 nur 685 © B. -

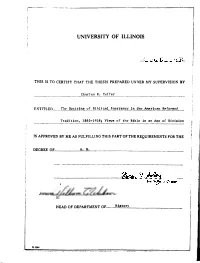

University of Illinois

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THIS tS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Charles K. Telfer ENTITLED......... The Doctrine oM bHcal.. T nerrancy. i nt ^ R? foiled Tradition, 1865-19185 Views of the Bible in an Arc of Division IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF............................. ............................................................................................................................ HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF. OII64 THE DOCTRINE OF BIBLICAL INERRANCY IN THE AMERICAN REFORMED TRADITION, 1865-1918 VIEWS OF THE BIBLE IN AN AGE OF DIVISION BY CHARLES K. TELFER THESIS for the DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS IN LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES College of Liberal Arts and Sciences University of Illinois Urbana, Illinois 1985 I. Introduction There is an increasing unanimity of opinion among historians of America’s cultural, intellectual, and religious history that the years between 1865 and 1935 form a distinct ’’epoch” or ’’period.” A number of important books published in recent years reflect this conception. Lefferts Loetscher in his masterly work on the Presbyterian Church entitled The Broadening Church (1954) deals with the years 1864 to 1936. In I960, George Marsden produced Fundamentalism and American Cultures The Shaping of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism, 1870-1925. In The Divided Mind of Protestant Amerlcat 1880-1930 (1982), Ferenc Szasz view9 these years as a distinct period in this country’s religious history.1 The years 1865 to 1935 may be typified as an ”age of division” for the American Protestant church. The church as a whole and particular denominations were rift by conflicts over important matters into ’’liberal” and ’’conservative” camps. Of course, the most well-known battles between ’’liberals” and ’’conservatives” took place in the twenties during the Modernist-Fundamentalist Controversy. -

Annihilationism

Annihilationism Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield Reprinted from "The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge," edited by Samuel Macauley Jackson, D.D., LL.D., i. pp. 183-186 (copyright by Funk and Wagnalls Company, New York, 1908). I. DEFINITION AND CLASSIFICATION OF THEORIES A term designating broadly a large body of theories which unite in contending that human beings pass, or are put, out of existence altogether. These theories fall logically into three classes, according as they hold that all souls, being mortal, actually cease to exist at death; or that, souls being naturally mortal, only those persist in life to which immortality is given by God; or that, though souls are naturally immortal and persist in existence unless destroyed by a force working upon them from without, wicked souls are actually thus destroyed. These three classes of theories may be conveniently called respectively, (1) pure mortalism, (2) conditional immortality, and (3) annihilationism proper. II. PURE MORTALISM The common contention of the theories which form the first of these classes is that human life is bound up with the organism, and that therefore the entire man passes out of being with the dissolution of the organism. The usual basis of this contention is either materialistic or pantheistic or at least pantheizing (e.g. realistic); the soul being conceived in the former case as but a function of organized matter and necessarily ceasing to exist with the dissolution of the organism, in the latter case as but the individualized manifestation of a much more extensive entity, back into which it sinks with the dissolution of the organism in connection with which the individualization takes place. -

Monergism Vs. Synergism – Part 1 Augustinianism, Pelagianism, and Semi-Pelagianism by John Brian Mckillop

Monergism vs. Synergism – Part 1 Augustinianism, Pelagianism, and Semi-Pelagianism by John Brian McKillop http://bit.ly/d24EHD In 1914, B.B. Warfield gave a series of lectures at Princeton. The lectures were later compiled into a book; The Plan of Salvation. In the section titled Autosoterism, Warfield states: There are fundamentally only two doctrines of salvation: that salvation is from God, and that salvation is from ourselves. The former is the doctrine of common Christianity; the latter is the doctrine of universal heathenism. 1 These two doctrines of salvation are known as Monergism and Synergism. In this article, I will attempt to define and illustrate each view; in a subsequent article, I will look at the Apostle John’s affirmation of Monergism in his Gospel. In a third article, I will present an edited transcript of a sermon that I preached on the topic; in a fourth article, I will look at each views inherent implications to the Great Commission. Definitions Theopedia defines Monergism as “the belief that the Holy Spirit is the only agent who effects the regeneration of Christians 2”; and defines Synergism as “essentially the view that God and humanity work together, each contributing their part to accomplish salvation in and for the individual 3.” Got Questions Ministries (in an article titled Monergism vs. synergism – which view is correct?) provides a similar definition of both terms: Monergism, which comes from a compound word in Greek that means “to work alone,” is the view that God alone effects our salvation. Synergism, which also comes from a compound Greek word meaning “to work together,” is the view that God works together with us in effecting salvation. -

The Plan of Salvation

Copyright ©Monergism Books The Plan of Salvation by Charles Hodge Table of Contents 1. God Has Such a Plan 2. Supralapsarianism 3. Infralapsarianism 4. "Hypothetical Redemption." 5. The Lutheran Doctrine as to the Plan of Salvation 6. The Remonstrant Doctrine 7. Wesleyan Arminianism 8. The Augustinian Scheme 9. Objections to the Augustinian Scheme 1. God has such a Plan The Scriptures speak of an Economy of Redemption; the plan or purpose of God in relation to the salvation of men. They call it in reference to its full revelation at the time of the advent, the οἰκονομία τοῦ πληρώματος τῶν καιρῶν, "The economy of the fulness of times." It is declared to be the plan of God in relation to his gathering into one harmonious body, all the objects of redemption, whether in heaven or earth, in Christ. Eph. 1:10. It is also called the οἰκονομία τοῦ μυστηρίου, the mysterious purpose or plan which had been hidden for ages in God, which it was the great design of the gospel to reveal, and which was intended to make known to principalities and powers, by the Church, the manifold wisdom of God. Eph. 3:9. A plan supposes: (1.) The selection of some definite end or object to be accomplished. (2.) The choice of appropriate means. (3.) At least in the case of God, the effectual application and control of those means to the accomplishment of the contemplated end. As God works on a definite plan in the external world, it is fair to infer that the same is true in reference to the moral and spiritual world. -

THE COVENANT of the SEVENTIETH WEEK by MEREDITH G. KLINE from the Law and the Prophets: Old Testament Studies in Honor of Oswald T

T he Covenant of the Seventieth Week, Kline | 1 THE COVENANT OF THE SEVENTIETH WEEK By MEREDITH G. KLINE from The Law and the Prophets: Old Testament Studies in Honor of Oswald T. Allis. ed. by J.H. Skilton. [Nutley, NJ]: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1974, pp. 452-469. In quick succession in the early forties, O. T. Allis published two major studies. In the first, he took up the cudgels against the modern critical assault on the Pentateuch; in the second, he dealt with a problem besetting the church from quite a different quarter. Like The Five Books of Moses (1943), Prophecy and the Church (1945) was a masterful critique. In part, surely, as a result of Allis's expose, dispensationalism does not seem to be quite as influential a movement in conservative churches as it was a generation or so ago. But the interpretation of Old Testament prophecies involved in the assessment of this evangelical heresy is as important and timely today as Allis found it to be then. By way of tribute to Dr. Allis I would turn to this second area of his publication interests, offering a study of the seventy weeks prophecy in Daniel 9, a passage which plays a dominant role in dispensationalism's futuristic charting. [1] Attention will focus particularly on the covenant mentioned in Daniel 9:27, for a proper understanding of this covenant speaks decisively against the peculiar concept of the "Great Tribulation" which dispensationalism derives from this verse and with which dispensationalism's identity is inseparably conjoined. The Unity of Daniel 9 If satisfactory results are to be achieved in the interpretation of the seventy weeks of Daniel 9, we will have to keep in mind that there is the closest relationship between Gabriel's prophecy (vss. -

Introduction: the Spirituali and Their Goals

NOT BY FAITH ALONE: VITTORIA COLONNA, MICHELANGELO AND REGINALD POLE AND THE EVANGELICAL MOVEMENT IN SIXTEENTH CENTURY ITALY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies Christopher Allan Dunn, J.D. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. March 19, 2014 NOT BY FAITH ALONE: VITTORIA COLONNA, MICHELANGELO AND REGINALD POLE AND THE EVANGELICAL MOVEMENT IN SIXTEENTH CENTURY ITALY Christopher Allan Dunn, J.D. MALS Mentor: Michael Collins, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Beginning in the 1530’s, groups of scholars, poets, artists and Catholic Church prelates came together in Italy in a series of salons and group meetings to try to move themselves and the Church toward a concept of faith that was centered on the individual’s personal relationship to God and grounded in the gospels rather than upon Church tradition. The most prominent of these groups was known as the spirituali, or spiritual ones, and it included among its members some of the most renowned and celebrated people of the age. And yet, despite the fame, standing and unrivaled access to power of its members, the group failed utterly to achieve any of its goals. By 1560 all of the spirituali were either dead, in exile, or imprisoned by the Roman Inquisition, and their ideas had been completely repudiated by the Church. The question arises: how could such a “conspiracy of geniuses” have failed so abjectly? To answer the question, this paper examines the careers of three of the spirituali’s most prominent members, Vittoria Colonna, Michelangelo and Reginald Pole. -

Not Quite Calvinist: Cyril Lucaris a Reconsideration of His Life and Beliefs

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU School of Theology and Seminary Graduate Papers/Theses School of Theology and Seminary 3-13-2018 Not Quite Calvinist: Cyril Lucaris a Reconsideration of His Life and Beliefs Stephanie Falkowski College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/sot_papers Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Falkowski, Stephanie, "Not Quite Calvinist: Cyril Lucaris a Reconsideration of His Life and Beliefs" (2018). School of Theology and Seminary Graduate Papers/Theses. 1916. https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/sot_papers/1916 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Theology and Seminary at DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Theology and Seminary Graduate Papers/Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOT QUITE CALVINIST: CYRIL LUCARIS A RECONSIDERATION OF HIS LIFE AND BELIEFS by Stephanie Falkowski 814 N. 11 Street Virginia, Minnesota A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Seminary of Saint John’s University, Collegeville, Minnesota, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Theology. SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY AND SEMINARY Saint John’s University Collegeville, Minnesota March 13, 2018 This thesis was written under the direction of ________________________________________ Dr. Shawn Colberg Director _________________________________________ Dr. Charles Bobertz Second Reader Stephanie Falkowski has successfully demonstrated the use of Greek and Latin in this thesis. -

What Is Monergistic Soteriology

Theological Distinctives 3. Monergistic View of Salvation Summary Major Supporters: Roman Catholicism/Eastern To have a Monergistic View of Salvation is to Orthodoxy/Erasmus/Joseph Arminius /John believe that man’s salvation is accomplished by God Wesley/Charles Finney alone. The debate between Monergism and Synergism Monergism describes the position in Christian continues to this day with Monergism typically being theology of those who believe that God, through the Holy associated with Calvinism/Reformed theology and Spirit, works to effectively bring about the salvation of Synergism typically being associated with Arminianism. individuals without cooperation from them. The Hospital Analogy Olive Drive Church holds to this position. To help understand the difference between synergism and monergism, think of two types of people in a A Brief History of Monergism vs. Synergism hospital. Historically, there have been two major views on the First, hospitals have really sick people. roles God and man play in bringing about the salvation Their sickness is killing them, and they need help. So the of man:1 doctor prescribes them a remedy and they in turn cooperate with the doctor by agreeing to the take the Monergism prescription. Because of the power of the doctor’s Salvation is accomplished by God alone without remedy coupled with the patient’s cooperation, the cooperation from man patient is healed and can leave the hospital with a renewed lease on life. Monergism is the idea that because of the depth of our sin, we are unable to come to Christ on our own Second, hospitals have morgues full of dead people.