A Study of the Idea of the VERBAL INSPIRATION OP the SCRIPTURES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Must Satan Be Released? Indeed He Must Be: Toward a Biblical Understanding of Revelation 20:3 Gregory H

Volume 25, Number 1 • Spring 2014 Must Satan Be Released? Indeed He Must Be: Toward a Biblical Understanding of Revelation 20:3 Gregory H. Harris Regaining Our Focus: A Response to the Social Action Trend in Evangelical Missions Joel James and Brian Biedebach The Seed of Abraham: A Theological Analysis of Galatians 3 and Its Implications for Israel Michael Riccardi A Review of Five Views on Biblical Inerrancy Norman L. Geisler THE MASTER’S SEMINARY JOURNAL published by THE MASTER’S SEMINARY John MacArthur, President Richard L. Mayhue, Executive Vice-President and Dean Edited for the Faculty: William D. Barrick John MacArthur Irvin A. Busenitz Richard L. Mayhue Nathan A. Busenitz Alex D. Montoya Keith H. Essex James Mook F. David Farnell Bryan J. Murphy Paul W. Felix Kelly T. Osborne Michael A. Grisanti Dennis M. Swanson Gregory H. Harris Michael J. Vlach Matthew W. Waymeyer by Richard L. Mayhue, Editor Michael J. Vlach, Executive Editor Dennis M. Swanson, Book Review Editor Garry D. Knussman, Editorial Consultant The views represented herein are not necessarily endorsed by The Master’s Seminary, its administration, or its faculty. The Master’s Seminary Journal (MSJ) is is published semiannually each spring and fall. Beginning with the May 2013 issue, MSJ is distributed electronically for free. Requests to MSJ and email address changes should be addressed to [email protected]. Articles, general correspondence, and policy questions should be directed to Dr. Michael J. Vlach. Book reviews should be sent to Dr. Dennis M. Swanson. The Master’s Seminary Journal 13248 Roscoe Blvd., Sun Valley, CA 91352 The Master’s Seminary Journal is indexed in Elenchus Bibliographicus Biblicus of Biblica; Christian Periodical Index; and Guide to Social Science & Religion in Periodical Literature. -

Georg Mancelius Teoloogina Juhendatud Disputatsioonide Põhjal

Tartu Ülikool Usuteaduskond MERLE KAND GEORG MANCELIUS TEOLOOGINA JUHENDATUD DISPUTATSIOONIDE PÕHJAL magistritöö juhendaja MARJU LEPAJÕE, MA Tartu 2010 Sisukord SISSEJUHATUS .................................................................................................... 4 TÄNU ..................................................................................................................... 9 I. LUTERLIK ORTODOKSIA............................................................................. 10 1.1. Ajastu üldiseloomustus .............................................................................. 10 1.1.1. Ajalooline ülevaade ............................................................................ 10 1.1.2. Ortodoksia tekkepõhjused................................................................... 13 1.2. Luterlik ortodoksia..................................................................................... 14 1.2.1. Periodiseering, tähtsamad esindajad ning koolkonnad....................... 14 1.2.2. Luterliku ortodoksia teoloogilised põhijooned ................................... 17 1.2.2.1. Pühakiri........................................................................................ 17 1.2.2.2. Õpetus Jumalast ........................................................................... 19 1.2.2.3. Loomisest ja inimese pattulangemisest........................................ 22 1.2.2.4. Ettehooldest ja ettemääratusest.................................................... 23 1.2.2.5. Vabast tahtest.............................................................................. -

THE REAL PRESENCE of CHRIST's BODY and BLOOD in the LORD's SUPPER: Contemporary Issues Concerning the Sacramental Union

THE REAL PRESENCE OF CHRIST'S BODY AND BLOOD IN THE LORD'S SUPPER: Contemporary Issues Concerning The Sacramental Union The great importance of the Lord's Supper is indicated by the fact that it is one of the few events of our Savior’s ministry which is recorded four times in the Holy Scriptures. Literally translated, these passages read: Matthew 26:26-28 jEsqiovntwn de; aujtw'n labw;n oJ jIhsou'" a[rton kai; eujloghvsa" e[klasen kai; dou;" toi'" maqhtai'" ei\pen: lavbete favgete, tou'to ejstin to; sw'ma mou. kai; labw;n pothvrion kai; eujcaristhvsa" e[dwken aujtoi'" levgwn: pivete ejx aujtou' pavnte", tou'to gavr ejstin to; ai|ma mou th'" diaqhvkh" to; peri; pollw'n 1 ejkcunnovmenon eij" a[fesin aJmartiw'n. While they were eating, Jesus, after he had taken bread and blessed [it], he broke [it] and, after he had given [it] to the disciples, he said, "Take, eat. This is my body.” And after he had taken a cup and given thanks, he gave [it] to them, saying, "Drink from it, all of you, for this is my blood of the covenant, which is being poured out for many unto the forgiveness of sins. Mark 14:22-24. Kai; ejsqiovntwn aujtw'n labw;n a[rton eujloghvsa" e[klasen kai; e[dwken aujtoi'" kai; ei\pen: lavbete, tou'to ejstin to; sw'ma mou. kai; labw;n pothvrion eujcaristhvsa" e[dwken aujtoi'", kai; e[pion ejx aujtou' pavnte". kai; ei\pen aujtoi'": tou'to ejstin to; ai|ma mou th'" diaqhvkh" to; ejkcunnovmenon uJpe;r pollw'n. -

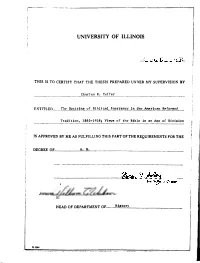

University of Illinois

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THIS tS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Charles K. Telfer ENTITLED......... The Doctrine oM bHcal.. T nerrancy. i nt ^ R? foiled Tradition, 1865-19185 Views of the Bible in an Arc of Division IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF............................. ............................................................................................................................ HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF. OII64 THE DOCTRINE OF BIBLICAL INERRANCY IN THE AMERICAN REFORMED TRADITION, 1865-1918 VIEWS OF THE BIBLE IN AN AGE OF DIVISION BY CHARLES K. TELFER THESIS for the DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS IN LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES College of Liberal Arts and Sciences University of Illinois Urbana, Illinois 1985 I. Introduction There is an increasing unanimity of opinion among historians of America’s cultural, intellectual, and religious history that the years between 1865 and 1935 form a distinct ’’epoch” or ’’period.” A number of important books published in recent years reflect this conception. Lefferts Loetscher in his masterly work on the Presbyterian Church entitled The Broadening Church (1954) deals with the years 1864 to 1936. In I960, George Marsden produced Fundamentalism and American Cultures The Shaping of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism, 1870-1925. In The Divided Mind of Protestant Amerlcat 1880-1930 (1982), Ferenc Szasz view9 these years as a distinct period in this country’s religious history.1 The years 1865 to 1935 may be typified as an ”age of division” for the American Protestant church. The church as a whole and particular denominations were rift by conflicts over important matters into ’’liberal” and ’’conservative” camps. Of course, the most well-known battles between ’’liberals” and ’’conservatives” took place in the twenties during the Modernist-Fundamentalist Controversy. -

Concordia Theological Quarterly

Concordia Theological Quarterly Volume 76:1-2 Januaryj April 2012 Table of Contents What Would Bach Do Today? Paul J. Grilne ........................................................................................... 3 Standing on the Brink of the J01'dan: Eschatological Intention in Deute1'onomy Geoffrey R. Boyle .................................................................................. 19 Ch1'ist's Coming and the ChUl'ch's Mission in 1 Thessalonians Charles A. Gieschen ............................................................................. 37 Luke and the Foundations of the Chu1'ch Pete1' J. Scaer .......................................................................................... 57 The Refonnation and the Invention of History Korey D. Maas ...................................................................................... 73 The Divine Game: Faith and the Reconciliation of Opposites in Luthe1"s Lectures on Genesis S.J. Munson ............................................................................................ 89 Fides Heroica? Luthe1" s P1'aye1' fo1' Melanchthon's Recovery f1'om Illness in 1540 Albert B. Collver III ............................................................................ 117 The Quest fo1' Luthe1'an Identity in the Russian Empire Darius Petkiinas .................................................................................. 129 The Theology of Stanley Hauerwas Joel D. Lehenbauer ............................................................................. 157 Theological Observer -

Concordia Theological Quarterly

Concordia Theological Quarterly Volume 76:1-2 Januaryj April 2012 Table of Contents What Would Bach Do Today? Paul J. Grilne ........................................................................................... 3 Standing on the Brink of the J01'dan: Eschatological Intention in Deute1'onomy Geoffrey R. Boyle .................................................................................. 19 Ch1'ist's Coming and the ChUl'ch's Mission in 1 Thessalonians Charles A. Gieschen ............................................................................. 37 Luke and the Foundations of the Chu1'ch Pete1' J. Scaer .......................................................................................... 57 The Refonnation and the Invention of History Korey D. Maas ...................................................................................... 73 The Divine Game: Faith and the Reconciliation of Opposites in Luthe1"s Lectures on Genesis S.J. Munson ............................................................................................ 89 Fides Heroica? Luthe1" s P1'aye1' fo1' Melanchthon's Recovery f1'om Illness in 1540 Albert B. Collver III ............................................................................ 117 The Quest fo1' Luthe1'an Identity in the Russian Empire Darius Petkiinas .................................................................................. 129 The Theology of Stanley Hauerwas Joel D. Lehenbauer ............................................................................. 157 Theological Observer -

Perkins Satellite Course of Study Sept. 23, Oct. 21, and Nov. 11 2017

COS 322: THEOLOGICAL HERITAGE III: MEDIEVAL & REFORMATION Perkins Satellite Course of Study Sept. 23, Oct. 21, and Nov. 11 2017 Dr. Bryan A. Stewart [email protected] Professor of Religion 325-793-3899 McMurry University Abilene, TX 79697 Course Description: This course provides an historically informed study of Medieval and Reformation Christian theology for students seeking to serve in ministerial capacities. As such, it covers major movements and events beginning with the split between the Eastern and Western church, and continues through the Protestant Reformation. Using primary sources, students will reflect on individuals, decisive events, and theological developments in the history of Medieval and Reformation Christianity. Course Objectives: 1. Understand major theological developments in medieval Christianity leading up to the Protestant Reformation. 2. Distinguish the theological characteristics of Luther, Zwingli, the Anabaptists, Calvin, the English Reformation, and the Puritans. 3. Understand and articulate Reformation-era debates concerning justification, sanctification, the sacraments, and church unity. 4. Appreciation and appropriation of the relevance of historical theology for pastoral ministry Required Texts: David Bagchi and David C. Steinmetz, eds., The Cambridge Companion to Reformation Theology (Cambridge: Cambridge U.P., 2004). ISBN: 978-0521776622. Henry Bettenson and Chris Maunder, Documents of the Christian Church, 4th ed. (Oxford: Oxford U.P., 2011). ISBN: 978-0199568987. Justo Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, Vol. 1: The Early Church to the Dawn of the Reformation, 2nd ed. (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2010). ISBN: 978-0061855887. -------------, The Story of Christianity, Vol. 2: The Reformation to the Present Day, 2nd ed. (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2010). ISBN: 978-0061855894. Recommended Resources (but not required): Cross & Livingston, eds., The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 3rd ed. -

500Th Anniversary of the Lutheran Reformation

500TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE LUTHERAN REFORMATION L LU ICA TH EL ER G A N N A S V Y E N E O H D T LUTHERAN SYNOD QUARTERLY VOLUME 57 • NUMBERS 2 & 3 JUNE & SEPTEMBER 2017 The journal of Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary ISSN: 0360-9685 LUTHERAN SYNOD QUARTERLY VOLUME 57 • NUMBERS 2 & 3 JUNE & SEPTEMBER 2017 The journal of Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary LUTHERAN SYNOD QUARTERLY EDITOR-IN-CHIEF........................................................... Gaylin R. Schmeling BOOK REVIEW EDITOR ......................................................... Michael K. Smith LAYOUT EDITOR ................................................................. Daniel J. Hartwig PRINTER ......................................................... Books of the Way of the Lord The Lutheran Synod Quarterly (ISSN: 0360-9685) is edited by the faculty of Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary 6 Browns Court Mankato, Minnesota 56001 The Lutheran Synod Quarterly is a continuation of the Clergy Bulletin (1941–1960). The purpose of the Lutheran Synod Quarterly, as was the purpose of the Clergy Bulletin, is to provide a testimony of the theological position of the Evangelical Lutheran Synod and also to promote the academic growth of her clergy roster by providing scholarly articles, rooted in the inerrancy of the Holy Scriptures and the Confessions of the Evangelical Lutheran Church. The Lutheran Synod Quarterly is published in March and December with a combined June and September issue. Subscription rates are $25.00 U.S. per year for domestic subscriptions and $35.00 U.S. per year for international subscriptions. All subscriptions and editorial correspondence should be sent to the following address: Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary Attn: Lutheran Synod Quarterly 6 Browns Ct Mankato MN 56001 Back issues of the Lutheran Synod Quarterly from the past two years are available at a cost of $10.00 per issue. -

Word of God in the Theology of Lutheran Orthodoxy 469 ROBERT D

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL MONTHLY Vol. XXXIII August 1962 No.8 The Will of God in the Ufe of a Christian 453 EUGENE F. KLUG The Word of God in the Theology of Lutheran Orthodoxy 469 ROBERT D. PREUS Homiletics 484 : \ Theological Observer 497 Book Review 502 EDITORIAL COMMITI'EE VICTOR BARTLING, PAUL M. BRBTSCHER ALFRED O. FUERBRINGER, GEORGE W. HOYER ARTHUR CARL PIEPKORN, WALTER R. ROEHRS LEWIS W. SPITZ, GILBERT A. THIELE Address all communications to the Editorial Committee m care of Walter R. Roehrs, 801 De Mun Ave., St. Louis .5, Mo. The Word of God in the Theology of Lutheran Orthodoxy By ROBERT D. PREUS (This is the third in a seri~s of study docu in making my observations: Martin Chem ments to be publish~d on the theme "The Theol ogy of the Word," originally prepared and nitz (1522-86), Jacob Heerbrand (1522 presented for discussion to the faculty of Con to 1600), Aegidius Hunnius (1550 to 'cordia Seminary, St. Louis, Mo. Previous articles 1603), Matthias Haffenreffer (1561 to on this topic appeared in this journal in Decem ber 1960 and May 1961.) 1619), Friedrich Balduin (1575-1627), Leonard Hutter (1563-1616), John Ger HE intention of this paper is not to hard (1582-1637), Caspar Brochmand Toffer a complete delineation of the (1585-1652), John Dorsch (1597 to doctrine of the Word of God in the 1659), John Huelsemann (1602-61), theology of Lutheran orthodoxy, a project John Danllhauer (1603-66), Michael entirely toO vast to be undertaken within Walther 0593-1662), Solomon Glassius v our limited space. -

On Interest and Usury*

Journal of Markets & Morality Volume 22, Number 2 (Fall 2019): 557–596 Copyright © 2019 On Interest Johann Gerhard * and Usury Translated by Richard J. Dinda Whether we should tolerate interest on borrowed money in the state. § 232. The second question1 is whether we should tolerate interest on bor- rowed money in the state. **How shameful and detestable this practice is becomes clear (1) from the authority of Him who forbids it; (2) from the nastiness of the sin, which conflicts with the Seventh Commandment and therefore is theft; (3) from the seriousness of the loss, for usury is so called from “biting” and “gnawing” because it consumes * Johann Gerhard, Commonplace XXVII, On Political Magistracy, in Locorum Theologi- corum Cum Pro Adstruenda Veritate, Tum Pro Destruenda quorumvis contradicen- tium falsitate, per These nervose, solide & copiose explicatorum Tomus Sextus: In quo continentur haec Capita: 26. De Ministerio Ecclesiastico. 27. De Magistratu Politico (Jena: Tobias Steinmann, 1619), pp. 911–45; reprint, Loci Theologici Cum Pro Adstruenda Veritate Tum Pro Destruenda Quorumvis Contradicentium Falsitate Per Theses Nervose Solide Et Copiose Explicati … Tomus Sextus (Berlin: Gust. Schlawitz, 1868), pp. 388–402. Copyright © 2019 Concordia Publishing House, www.cph.org. All rights reserved. On the English translation of Gerhard’s Theological Commonplaces, see www.cph.org/gerhard. In this translation, all Gerhard’s original in-text references have been retained. All footnotes are the work of the editors. 1 The question on interest and usury (§§ 232–56) falls within Gerhard’s consideration of various matters of civil law in a Christian state. The preceding question (§ 231) concerns the establishment of places of refuge for asylum seekers. -

A Lively Legacy Essays in Honor of Robert Preus ,,I

- - ------~---- - -- - -------- '-~ -- -----·----··-- . A LIVELY LEGACY ESSAYS IN HONOR OF ROBERT PREUS ,,I A LIVELY LEGACY: ESSAYS IN HONOR OF ROBERT PREUS Co-editors: Kurt E. Marquart John R. Stephenson Bjarne W. Teigen The cover design is a reproduction of the Preus family coat of arms. Library of Congress Catalog Number 85-73168 ISBN# 0-9615927-0-2 (hardbound) ISBN# 0-9615927-1-0 (paperback) Copyright by Concordia Theological Seminary Fort Wayne, Indiana 1985 Printed by Graphic Publishing Co., Inc. Lake Mills, Iowa 50450 11 Table of Contents List of Contributors . v Editorial Preface . vii Doctor Robert David Preus: An Appreciation . ix 1. Ulrich Asendorf Luther's Sermons on Advent as a Summary of his Theology . 1 / 2. Eugene W. Bunkowske Was Luther a Missionary?........... 15 3. Seth Erlandsson The Unity of Isaiah: A New Solution?. 33 4. Henry P. Hamann Apartheid and (the) STATUS CON- FESSIONIS . 40 5. Tom G. A. Hardt Justification and Easter. A Study in Subjective and Objective Justification in Lutheran Theology . 52 6. Gottfried Hoffmann The Baptism and Faith of Children. 79 7. Richard Klann Luther on Teaching Christian Ethics . 96 8. Cameron A. MacKenzie The Enduring Witness of the Old Testament ........................ 105 9. Kurt E. Marquart The Reformation Roots of "Objective Justification" . 117 10. Daniel Ch. Overduin Ethical Reflections on the Contempo- rary IVF Technology ............... 131 11. Hans-Lutz Poetsch What is Involved in the Infallibility of Jesus Christ? . 143 12. John R. Stephenson The Holy Eucharist: at the Center or Periphery of the Church's Life in Luther's Thinking? ................. 154 13. Bjarne W. Teigen Martin Chemnitz and SD VII, 126 . -

INSTITUTES of the CHRISTIAN RELIGION VOL. 1 Translated by Ford Lewis Battles

THE AGES DIGITAL LIBRARY THEOLOGY INSTITUTES OF THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION VOL. 1 Translated by Ford Lewis Battles Used by permission from The Westminster Press All Rights Reserved B o o k s F o r Th e A g e s AGES Software • Albany, OR USA Version 1.0 © 1998 2 JOHN CALVIN: INSTITUTES OF THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION EDITED BY JOHN T. MCNEILL Auburn Professor Emeritus of Church History Union Theological Seminary New York TRANSLATED AND INDEXED BY FORD LEWIS BATTLES Philip Schaff Professor of Church History The Hartford Theological Seminary Hartford, Connecticut in collaboration with the editor and a committee of advisers Philadelphia 3 GENERAL EDITORS’ PREFACE The Christian Church possesses in its literature an abundant and incomparable treasure. But it is an inheritance that must be reclaimed by each generation. THE LIBRARY OF CHRISTIAN CLASSICS is designed to present in the English language, and in twenty-six volumes of convenient size, a selection of the most indispensable Christian treatises written prior to the end of the sixteenth century. The practice of giving circulation to writings selected for superior worth or special interest was adopted at the beginning of Christian history. The canonical Scriptures were themselves a selection from a much wider literature. In the patristic era there began to appear a class of works of compilation (often designed for ready reference in controversy) of the opinions of well-reputed predecessors, and in the Middle Ages many such works were produced. These medieval anthologies actually preserve some noteworthy materials from works otherwise lost. In modern times, with the increasing inability even of those trained in universities and theological colleges to read Latin and Greek texts with ease and familiarity, the translation of selected portions of earlier Christian literature into modern languages has become more necessary than ever; while the wide range of distinguished books written in vernaculars such as English makes selection there also needful.