The Fitness of Scripture: Richard Chenevix Trench and Victorian Doctrines of Scripture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Must Satan Be Released? Indeed He Must Be: Toward a Biblical Understanding of Revelation 20:3 Gregory H

Volume 25, Number 1 • Spring 2014 Must Satan Be Released? Indeed He Must Be: Toward a Biblical Understanding of Revelation 20:3 Gregory H. Harris Regaining Our Focus: A Response to the Social Action Trend in Evangelical Missions Joel James and Brian Biedebach The Seed of Abraham: A Theological Analysis of Galatians 3 and Its Implications for Israel Michael Riccardi A Review of Five Views on Biblical Inerrancy Norman L. Geisler THE MASTER’S SEMINARY JOURNAL published by THE MASTER’S SEMINARY John MacArthur, President Richard L. Mayhue, Executive Vice-President and Dean Edited for the Faculty: William D. Barrick John MacArthur Irvin A. Busenitz Richard L. Mayhue Nathan A. Busenitz Alex D. Montoya Keith H. Essex James Mook F. David Farnell Bryan J. Murphy Paul W. Felix Kelly T. Osborne Michael A. Grisanti Dennis M. Swanson Gregory H. Harris Michael J. Vlach Matthew W. Waymeyer by Richard L. Mayhue, Editor Michael J. Vlach, Executive Editor Dennis M. Swanson, Book Review Editor Garry D. Knussman, Editorial Consultant The views represented herein are not necessarily endorsed by The Master’s Seminary, its administration, or its faculty. The Master’s Seminary Journal (MSJ) is is published semiannually each spring and fall. Beginning with the May 2013 issue, MSJ is distributed electronically for free. Requests to MSJ and email address changes should be addressed to [email protected]. Articles, general correspondence, and policy questions should be directed to Dr. Michael J. Vlach. Book reviews should be sent to Dr. Dennis M. Swanson. The Master’s Seminary Journal 13248 Roscoe Blvd., Sun Valley, CA 91352 The Master’s Seminary Journal is indexed in Elenchus Bibliographicus Biblicus of Biblica; Christian Periodical Index; and Guide to Social Science & Religion in Periodical Literature. -

A University Microfilms International

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Organizing Knowledge: Comparative Structures of Intersubjectivity in Nineteenth-Century Historical Dictionaries

Organizing Knowledge: Comparative Structures of Intersubjectivity in Nineteenth-Century Historical Dictionaries Kelly M. Kistner A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Gary G. Hamilton, Chair Steven Pfaff Katherine Stovel Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Sociology ©Copyright 2014 Kelly M. Kistner University of Washington Abstract Organizing Knowledge: Comparative Structures of Intersubjectivity in Nineteenth-Century Historical Dictionaries Kelly Kistner Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Gary G. Hamilton Sociology Between 1838 and 1857 language scholars throughout Europe were inspired to create a new kind of dictionary. Deemed historical dictionaries, their projects took an unprecedented leap in style and scale from earlier forms of lexicography. These lexicographers each sought to compile historical inventories of their national languages and were inspired by the new scientific approach of comparative philology. For them, this science promised a means to illuminate general processes of social change and variation, as well as the linguistic foundations for cultural and national unity. This study examines two such projects: The German Dictionary, Deutsches Worterbuch, of the Grimm Brothers, and what became the Oxford English Dictionary. Both works utilized collaborative models of large-scale, long-term production, yet the content of the dictionaries would differ in remarkable ways. The German dictionary would be characterized by its lack of definitions of meaning, its eclectic treatment of entries, rich analytical prose, and self- referential discourse; whereas the English dictionary would feature succinct, standardized, and impersonal entries. Using primary source materials, this research investigates why the dictionaries came to differ. -

Body and Mind

PUBLI8HED SUBSCRIPTION PRICE MONTHLY 41.76 PER YEAR No. 145- PRICE 15 CENTS NOV. 1891 THE HUMBOLDT L1BRARY5CIENCE BODY AND MISB SURCuON UEHEnAL’S v With OtheiL EsgAys~ * K j , l BY WILLIAM KINGDON CLIFFORD NEW YORK THE HUMBOLDT PUBLISHING COMPANY 19 ASTOR PLACE ENTERED AT THE NEW YORK POST OFFICE AS SECOND CLASS MATTER. The Social Science Library OF THE BEST AUTHORS. PUBLISHED MONTHLY AT POPULAR PRICES. W. D. P. BLISS, Editor. cents each or a 12 Paper Cover, 25 , $2.50 Tearfor Numbers. Cloth, extra, “ “ 7.J0 “ “ “ “ Which prices include postage to any part of theUnited States, Canada, or Mexico. Subscriptions may commence at any number and are payable in advance. NOW READY. x. SIX CENTURIES OF WORK AND WAGES. By James E. Thorold Rogers, M. P. Abridged, with charts and summary. By W. D. P. Buss. Introduction by Prof. R. T. Ely. а. THE SOCIALISM OF JOHN STUART MILL. The only collection of Mill’s writings on Socialism. 3 THE SOCIALISM AND UNSOCIALISM OF THOMAS CARLYLE. A collection of Carlyle’s social writings; together with Joseph Mazzini’s famous essay protesting against Carlyle’s views. Vol. I. 4. THE SOCIALISM AND UNSOCIALISM OF THOMAS CARLYLE. Vol. II. 5. WILLIAM MORRIS, POET, ARTIST, SOCIALIST. A selection from his writings together with a sketch of the man. Edited by Francis Watts Lee. б. THE FABIAN ESSAYS. American edition, with introduction and notes, by H. G. WILSHIRE. 7. THE ECONOMICS OF HERBERT SPENCER. By W. C. Owen. 8. THE COMMUNISM OF JOHN RUSKIN. 9. HORACE GREELEY; FARMER, EDITOR, AND SOCIALIST. -

The Armstrong Papers P6-Part1

The Armstrong Papers P6 Part I Armstrong of Moyaliffe Castle, County Tipperary University of Limerick Library and Information Services University of Limerick Special Collections The Armstrong Papers Reference Code: IE 2135 P6 Title: The Armstrong Papers Dates of Creation: 1662-1999 Level of Description: Sub-Fonds Extent and Medium: 133 boxes, 2 outsize items (2554 files) CONTEXT Name of Creator(s): The Armstrong family of Moyaliffe Castle, county Tipperary, and the related families of Maude of Lenaghan, county Fermanagh; Everard of Ratcliffe Hall, Leicestershire; Kemmis of Ballinacor, county Wicklow; Russell of Broadmead Manor, Kent; and others. Biographical History: The Armstrongs were a Scottish border clan, prominent in the service of both Scottish and English kings. Numerous and feared, the clan is said to have derived its name from a warrior who during the Battle of the Standard in 1138 lifted a fallen king onto his own horse with one arm after the king’s horse had been killed under him. In the turbulent years of the seventeenth century, many Armstrongs headed to Ireland to fight for the Royalist cause. Among them was Captain William Armstrong (c. 1630- 1695), whose father, Sir Thomas Armstrong, had been a supporter of Charles I throughout the Civil War and the Commonwealth rule, and had twice faced imprisonment in the Tower of London for his support for Charles II. When Charles II was restored to power, he favoured Captain William Armstrong with a lease of Farneybridge, county Tipperary, in 1660, and a grant of Bohercarron and other lands in county Limerick in 1666. In 1669, William was appointed Commissioner for Payroll Tax, and over the next ten years added to his holdings in the area, including the former lands of Holy Cross Abbey and the lands of Ballycahill. -

Benjamin Jowett (1817-1893)

Centre for Idealism and the New Liberalism Working Paper Series: Number 4 Bibliography of Benjamin Jowett (1817-1893) (2018 version) Compiled by Professor Colin Tyler Centre for Idealism and the New Liberalism University of Hull Every Working Paper is peer reviewed prior to acceptance. Authors & compilers retain copyright in their own Working Papers. For further information on the Centre for Idealism and the New Liberalism, and its activities, visit our website: http://www.hull.ac.uk/pas/ Or, contact the Centre Directors Colin Tyler: [email protected] James Connelly [email protected] Centre for Idealism and the New Liberalism School of Law and Politics University of Hull, Cottingham Road Hull, HU6 7RX, United Kingdom Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 I. Writings 4 II. Reviews and obituaries 6 III. Other discussions 13 IV. Newspaper reports regarding Benjamin Jowett 18 V. Jowett papers 19 2 Acknowledgments for the 2017 version Once again, I am pleased to thank scholars who sent in references, and hope they will not mind my not mentioning them individually. All future references will be received with thanks. Professor Colin Tyler University of Hull December 2017 Acknowledgments for original, 2004 version The work on this bibliography was supported by a Resource Enhancement Award (B/RE/AN3141/APN17357) from the Arts and Humanities Research Board. ‘The Arts and Humanities Research Board (AHRB) funds postgraduate and advanced research within the UK’s higher education institutions and provides funding for museums, galleries and collections that are based in, or attached to, HEIs within England. The AHRB supports research within a huge subject domain - from ‘traditional’ humanities subjects, such as history, modern languages and English literature, to music and the creative and performing arts.’ I have also profited enormously from having access to the Brynmor Jones Library at the University of Hull, a resource which benefits from an excellent stock of written and electronic sources, as well as extremely helpful and friendly librarians. -

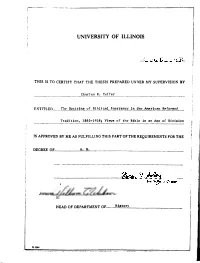

University of Illinois

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THIS tS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Charles K. Telfer ENTITLED......... The Doctrine oM bHcal.. T nerrancy. i nt ^ R? foiled Tradition, 1865-19185 Views of the Bible in an Arc of Division IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF............................. ............................................................................................................................ HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF. OII64 THE DOCTRINE OF BIBLICAL INERRANCY IN THE AMERICAN REFORMED TRADITION, 1865-1918 VIEWS OF THE BIBLE IN AN AGE OF DIVISION BY CHARLES K. TELFER THESIS for the DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS IN LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES College of Liberal Arts and Sciences University of Illinois Urbana, Illinois 1985 I. Introduction There is an increasing unanimity of opinion among historians of America’s cultural, intellectual, and religious history that the years between 1865 and 1935 form a distinct ’’epoch” or ’’period.” A number of important books published in recent years reflect this conception. Lefferts Loetscher in his masterly work on the Presbyterian Church entitled The Broadening Church (1954) deals with the years 1864 to 1936. In I960, George Marsden produced Fundamentalism and American Cultures The Shaping of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism, 1870-1925. In The Divided Mind of Protestant Amerlcat 1880-1930 (1982), Ferenc Szasz view9 these years as a distinct period in this country’s religious history.1 The years 1865 to 1935 may be typified as an ”age of division” for the American Protestant church. The church as a whole and particular denominations were rift by conflicts over important matters into ’’liberal” and ’’conservative” camps. Of course, the most well-known battles between ’’liberals” and ’’conservatives” took place in the twenties during the Modernist-Fundamentalist Controversy. -

EDWARD THOMAS: Towards a Complete Checklist of His

Edward Thomas: A Checklist © Jeff Cooper EDWARD THOMAS Towards a Complete Checklist Of His Published Writings Compiled by Jeff Cooper First published in Great Britain in 2004 by White Sheep Press Second edition published on-line in 2013; third edition, 2017 © 2013, 2017 Jeff Cooper All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied or reproduced for publication or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise stored in a retrieval system, without the prior permission of the copyright owner and the publishers. The rights of Jeff Cooper to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Preface This is the third edition, with some additions and amendments (and a complete re-numbering), of the edition originally published in 2004 under Richard Emeny’s name, with myself as the editor. The interest in Edward Thomas’s poetry and prose writings has grown considerably over the past few years, and this is an opportune moment to make the whole checklist freely available and accessible. The intention of the list is to provide those with an interest in Thomas with the tools to understand his enormous contribution to criticism as well as poetry. This is very much a work in progress. I can’t say that I have produced a complete or wholly accurate list, and any amendments or additions would be gratefully received by sending them to me at [email protected]. They will be incorporated in the list and acknowledged. -

Two Books on the Victorian Interest in Hellenism

Journal of The Faculty of Environmental Science and Technology, Okayama University Vo1.2, No.1, pp.169-174, January 1997 Two Books on the Victorian Interest in Hellenism Masaru OGINO* (Received October 29, 1996) In the 1980s there appeared two books about the Victorian attitude toward the ancient Greeks, or about how the Victorians felt about and incorporated the ancient Greek culture. The two books are Richard Jenkyn, The Victorians and Ancient Greece (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1980) and Frank M Turner, The Greek Herita.ge in Victorian Britain (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984). Although they deal with the same subject, their approaches toward the subject are quite different from each other. In this paper, I will pick up two themes from each book- - "Greek Gods and Mythology" and .. Plato and his Philosophy" -- and see the difference in their approaches. 1. INTRODUCTION The Victorians and Ancient Greece by Richard Jenkyns and The Greek Herimge in Victorian Brimm by Frank M Turner- - these two books seem to be like each other; judging from their titles, they seem to give us the same kind of stories about the Victorian attitude toward the ancient Greece. But as it turns out, these two books are totally unlike each other. Of course, no two books are not, or should not, be the same, even if they treat the same subject matter. But in the case of the two books mentioned above, despite the identity of the subject matter- - the Victorians' approaches to the ancient Greeks- - they are almost diametrically different from each other. That is, although they deal with the same subject, their approaches to the subject are completely different Jenkyns' book gives us a general view of how the Victorians accepted the various heritages of the ancient Greek culture, while Turner's book, limiting itself to the main famous figures, gives an academic account of how the Victorians tried to understand the ancient Greeks and to incorporate them into their own age. -

Ordination Sermons: a Bibliography1

Ordination Sermons: A Bibliography1 Aikman, J. Logan. The Waiting Islands an Address to the Rev. George Alexander Tuner, M.B., C.M. on His Ordination as a Missionary to Samoa. Glasgow: George Gallie.. [etc.], 1868. CCC. The Waiting Islands an Address to the Rev. George Alexander Tuner, M.B., C.M. on His Ordination as a Missionary to Samoa. Glasgow: George Gallie.. [etc.], 1868. Aitken, James. The Church of the Living God Sermon and Charge at an Ordination of Ruling Elders, 22nd June 1884. Edinburgh: Robert Somerville.. [etc.], 1884. Allen, William. The Minister's Warfare and Weapons a Sermon Preached at the Installation of Rev. Seneca White at Wiscasset, April 18, 1832. Brunswick [Me.]: Press of Joseph Grif- fin, 1832. Allen, Willoughby C. The Christian Hope. London: John Murray, 1917. Ames, William, Dan Taylor, William Thompson, of Boston, and Benjamin. Worship. The Re- spective Duties of Ministers and People Briefly Explained and Enforced the Substance of Two Discourses, Delivered at Great-Yarmouth, in Norfolk, Jan. 9th, 1775, at the Ordina- tion of the Rev. Mr. Benjamin Worship, to the Pastoral Office. Leeds: Printed by Griffith Wright, 1775. Another brother. A Sermon Preach't at a Publick Ordination in a Country Congregation, on Acts XIII. 2, 3. Together with an Exhortation to the Minister and People. London: Printed for John Lawrance.., 1697. Appleton, Nathaniel, and American Imprint Collection (Library of Congress). How God Wills the Salvation of All Men, and Their Coming to the Knowledge of the Truth as the Means Thereof Illustrated in a Sermon from I Tim. II, 4 Preached in Boston, March 27, 1753 at the Ordination of the Rev. -

The Influence of Aristotelian Rhetoric on J.H. Newman's Epistemology 1

DOI 10.1515/znth-2014-0001 — znth 2014; 21(1): 192-225 GRUYTER Andrew Meszaros The Influence of Aristotelian Rhetoric on J.H. Newman’s Epistemology Abstract: The article examines the influence of Aristotelian rhetorical theory on the epistemology of Newman. This influence is established on historical grounds and by similarity of content. Specifically, the article sheds light on how the rhetorical notions of ethos, logos, and pathos are all implicitly incorporated into Newman’s theory of knowledge concerning the concrete. The section on rhetori- cal ethos focuses on Newman’s appeal to the “prudent man.” Concerning logos, particular attention is paid to the rhetorical enthymeme and in what sense Newman’s method of argument (Informal and Natural Inference) can justiflably be described as enthymematic. Pathos, in turn, is shown to be significant for the way in which N e ^ a n views foe subjective dimension of foe individual’s coming to knowledge. The rhetorical rationality that emerges sets the stage for claritying, in another context, other more theological themes in Newman’s writings, such as his religious apologetic, his understanding of tradition, and even his Christolo^f. ,Leuven (ﻻ)<ا Andrew Meszaros: Systematische Theeiegie, Katoolleke Universiteit Leuven, E-Mail:[email protected] ﻣﻬﻪ 3م1 ه1 وSt-Michielsstraat 4 bus 1 Introducían In hisAn Essay in theAid ofa Grammar ofAssent (1870), Newman tried to justity foe claim that believers without knowledge of arguments for their faith are never- tireless reasonable in assenting to that faith. Engaging foe rationalists and foe agnostics, Newman attempted to illustrate that even foe educated person’s faith does not ultimately rely on textbook syllogisms, but rather “on personal reasonings and implicit workings of the mind, which cannot be adequately put into words.”* Newman’s Cratorian confrère in Birmingham, Edward Caswall (1814-1878), sums up Newman’s intentions with his notes scribbled in his copy of the Grammar after a conversation with Newman: ‘Object of foe book twofold. -

The Canterbury Association

The Canterbury Association (1848-1852): A Study of Its Members’ Connections By the Reverend Michael Blain Note: This is a revised edition prepared during 2019, of material included in the book published in 2000 by the archives committee of the Anglican diocese of Christchurch to mark the 150th anniversary of the Canterbury settlement. In 1850 the first Canterbury Association ships sailed into the new settlement of Lyttelton, New Zealand. From that fulcrum year I have examined the lives of the eighty-four members of the Canterbury Association. Backwards into their origins, and forwards in their subsequent careers. I looked for connections. The story of the Association’s plans and the settlement of colonial Canterbury has been told often enough. (For instance, see A History of Canterbury volume 1, pp135-233, edited James Hight and CR Straubel.) Names and titles of many of these men still feature in the Canterbury landscape as mountains, lakes, and rivers. But who were the people? What brought these eighty-four together between the initial meeting on 27 March 1848 and the close of their operations in September 1852? What were the connections between them? In November 1847 Edward Gibbon Wakefield had convinced an idealistic young Irishman John Robert Godley that in partnership they could put together the best of all emigration plans. Wakefield’s experience, and Godley’s contacts brought together an association to promote a special colony in New Zealand, an English society free of industrial slums and revolutionary spirit, an ideal English society sustained by an ideal church of England. Each member of these eighty-four members has his biographical entry.