My First Article' Explored the Ground on Which a New Approach to the Doctrine of Revelation and Inspiration Could Be Eventually Developed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Must Satan Be Released? Indeed He Must Be: Toward a Biblical Understanding of Revelation 20:3 Gregory H

Volume 25, Number 1 • Spring 2014 Must Satan Be Released? Indeed He Must Be: Toward a Biblical Understanding of Revelation 20:3 Gregory H. Harris Regaining Our Focus: A Response to the Social Action Trend in Evangelical Missions Joel James and Brian Biedebach The Seed of Abraham: A Theological Analysis of Galatians 3 and Its Implications for Israel Michael Riccardi A Review of Five Views on Biblical Inerrancy Norman L. Geisler THE MASTER’S SEMINARY JOURNAL published by THE MASTER’S SEMINARY John MacArthur, President Richard L. Mayhue, Executive Vice-President and Dean Edited for the Faculty: William D. Barrick John MacArthur Irvin A. Busenitz Richard L. Mayhue Nathan A. Busenitz Alex D. Montoya Keith H. Essex James Mook F. David Farnell Bryan J. Murphy Paul W. Felix Kelly T. Osborne Michael A. Grisanti Dennis M. Swanson Gregory H. Harris Michael J. Vlach Matthew W. Waymeyer by Richard L. Mayhue, Editor Michael J. Vlach, Executive Editor Dennis M. Swanson, Book Review Editor Garry D. Knussman, Editorial Consultant The views represented herein are not necessarily endorsed by The Master’s Seminary, its administration, or its faculty. The Master’s Seminary Journal (MSJ) is is published semiannually each spring and fall. Beginning with the May 2013 issue, MSJ is distributed electronically for free. Requests to MSJ and email address changes should be addressed to [email protected]. Articles, general correspondence, and policy questions should be directed to Dr. Michael J. Vlach. Book reviews should be sent to Dr. Dennis M. Swanson. The Master’s Seminary Journal 13248 Roscoe Blvd., Sun Valley, CA 91352 The Master’s Seminary Journal is indexed in Elenchus Bibliographicus Biblicus of Biblica; Christian Periodical Index; and Guide to Social Science & Religion in Periodical Literature. -

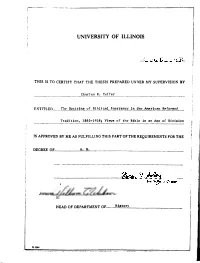

University of Illinois

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THIS tS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Charles K. Telfer ENTITLED......... The Doctrine oM bHcal.. T nerrancy. i nt ^ R? foiled Tradition, 1865-19185 Views of the Bible in an Arc of Division IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF............................. ............................................................................................................................ HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF. OII64 THE DOCTRINE OF BIBLICAL INERRANCY IN THE AMERICAN REFORMED TRADITION, 1865-1918 VIEWS OF THE BIBLE IN AN AGE OF DIVISION BY CHARLES K. TELFER THESIS for the DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS IN LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES College of Liberal Arts and Sciences University of Illinois Urbana, Illinois 1985 I. Introduction There is an increasing unanimity of opinion among historians of America’s cultural, intellectual, and religious history that the years between 1865 and 1935 form a distinct ’’epoch” or ’’period.” A number of important books published in recent years reflect this conception. Lefferts Loetscher in his masterly work on the Presbyterian Church entitled The Broadening Church (1954) deals with the years 1864 to 1936. In I960, George Marsden produced Fundamentalism and American Cultures The Shaping of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism, 1870-1925. In The Divided Mind of Protestant Amerlcat 1880-1930 (1982), Ferenc Szasz view9 these years as a distinct period in this country’s religious history.1 The years 1865 to 1935 may be typified as an ”age of division” for the American Protestant church. The church as a whole and particular denominations were rift by conflicts over important matters into ’’liberal” and ’’conservative” camps. Of course, the most well-known battles between ’’liberals” and ’’conservatives” took place in the twenties during the Modernist-Fundamentalist Controversy. -

Protestant Experience and Continuity of Political Thought in Early America, 1630-1789

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School July 2020 Protestant Experience and Continuity of Political Thought in Early America, 1630-1789 Stephen Michael Wolfe Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Political History Commons, Political Theory Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Wolfe, Stephen Michael, "Protestant Experience and Continuity of Political Thought in Early America, 1630-1789" (2020). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5344. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5344 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. PROTESTANT EXPERIENCE AND CONTINUITY OF POLITICAL THOUGHT IN EARLY AMERICA, 1630-1789 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Political Science by Stephen Michael Wolfe B.S., United States Military Academy (West Point), 2008 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2016, 2018 August 2020 Acknowledgements I owe my interest in politics to my father, who over the years, beginning when I was young, talked with me for countless hours about American politics, usually while driving to one of our outdoor adventures. He has relentlessly inspired, encouraged, and supported me in my various endeavors, from attending West Point to completing graduate school. -

Cautions About the Reformation and Its Theologies Dr

Cautions about the Reformation and Its Theologies Dr. David Saxon Maranatha Baptist University I. It was not a primitivist movement – restoration of the NT ideal – but rather a reformatory movement – restoration of the ideal of catholicity A. Affirmed scripture’s sole authority but embraced the 5th century father Vincent of Lerins’ formula that the catholic faith is “What is believed everywhere, at all times, and by all.” B. Viewed “catholicity” as an ideal achieved in the early church and still desirable 1. “The distinctive ideas which thinkers such as Luther and Calvin held to underlie Christian faith and practice had been obscured, if not totally perverted, through a series of developments in the Middle Ages. According to these and other reformers of that age, it was time to reverse these changes, to undo the work of the Middle Ages, in order to return to a purer, fresher version of Christianity which beckoned to them across the centuries. The reformers echoed the cry of the humanists: ‘back to the sources’ (ad fontes) – back to the Golden Age of the church, in order to reclaim its freshness, purity and vitality in the midst of a period of stagnation and corruption” (Timothy George, Reformation Thought, 3-4). 2. Mainline reformers constantly quoted Augustine and other church fathers to establish the antiquity of their theology. This is understandable because the Catholics were claiming the church fathers for their many theological aberrations, and their claims were clearly not true. 3. But the church fathers, including even Augustine, got a long of things wrong, and the ultimate appeal needed to bypass them and go directly to the Scriptures. -

A Liberal Protestant Reflection on Erik Borgman's Cultural Theology

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 8 Original Research ‘Something is recognised’: A liberal Protestant reflection on Erik Borgman’s cultural theology Author: The Dutch Roman Catholic theologian Erik Borgman (1957), who developed a cultural 1,2 Rick Benjamins theology, was appointed as a visiting professor at the liberal Protestant theological Mennonite Affiliations: Seminary in Amsterdam. In this article, his progressive Roman Catholic theology is compared 1Protestant Theological to a liberal Protestant approach. The historical backgrounds of these different types of theology University, Amsterdam/ are expounded, all the way back to Aquinas and Scotus, in order to clarify their specific Groningen, the Netherlands & character for the sake of a better mutual understanding. Next, the convergence of these two Faculty of Theology and Religious Studies, University types of theology in the twentieth century is explained with reference to the philosophy of of Groningen, the Netherlands Heidegger. Finally, the difficulties posed by postmodern philosophies to both a progressive Roman Catholic theology and a liberal Protestant theology are shown. It is asserted that both 2Department of Dogmatics types of theology claim that the insights of their particular tradition can be relevant beyond and Christian Ethics, Faculty of Theology, University of this tradition to modern and postmodern humans. Pretoria, South Africa Project leader: D.P. Veldsman A conference was held on 16 October 2015 on the occasion of the joining of Erik Borgman as a Project number: 01224719 visiting professor at the Mennonite Seminary (doopsgezind seminarie) in Amsterdam.1 Borgman (1957), the biographer of the famous theologian Edward Schillebeeckx (Borgman 2002), is a Description: Prof. -

A Study of the Idea of the VERBAL INSPIRATION OP the SCRIPTURES

A Study of the Idea of THE VERBAL INSPIRATION OP THE SCRIPTURES with special reference to. the Reformers and Post-Reformation Thinkers of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Divinity of the University of Edinburgh in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Ph.D. degree. Allan Andrew Zaun, B.A., B.D- May 15,1937 PREFACE. At the outset of this study it will be well to define terms. By "verbal Inspiration11 we mean the theory which main tains that in the process of recording the Scriptures, the Holy Spirit Himself selected the very words which the writers used. In the same sense that Milton is the author of Paradise Lost, the Holy Spirit is held to be the author of Scripture. Whether communicated by suggestion or actual dictation, the words of the text are the exact words, and no other, which God wished to have employed. The form, as well as the content, is liter ally given by Gk>d. This, briefly, is the verbal theory. We recognize the intimate, but not absolutely inseparable, con nection between thought and language. To the extent that words can be an adequate expression of the thought, Inspiration is verbal; however, the classic formulation of the doctrine, in its insistence upon dictation and verbal inerrancy, introduced mechanical features with which many scholars today cannot find themselves in full agreement. In the Reformation and post-Reformation periods we are confining our study principally to the dogmaticians of Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands; nq attempt has been made to trace the development of the doctrine in England and Scotland, which, however, were profoundly influenced by the Genevan Reformation. -

Introduction 1

The Search for Anglican Identity M. H. Turner Table of Contents Introduction 1 The Anglican Disposition? 4 The Anglican Branch? 9 The Anglican Via Media? 18 The Anglican Attraction? 28 Why Does There Need to Be a Search for Anglican Identity? 33 Conclusion 44 Introduction The word Anglicanism may seem surprisingly difficult to define. The task might even seem impossible. Almost two millennia ago one could speak of the church in England, and in time it became clear there was a church of England. But even at the Reformation there was nothing called “Anglicanism.” No one at the time would have thought of Anglicanism as a different expression of the Christian faith, as if the town of Wittenberg might have needed an “Anglican” church down the street from a “Lutheran” one. By the time there is a clear idea of Anglicanism as a distinct ism, we are certainly past the Restoration, and we might even be into the nineteenth 1 century. Today we are in what could be called the long nineteenth century, with no end to the Anglican definitional wars, because there is no definition that can comprehend the vast diversity of what travels under that name. It would be like trying to come up with a definition for Catholicism if there were no pope, no mass, and so on. Yet we must say something about Anglican identity, at least if we want to give an account to ourselves and to others of what we are. The search for Anglican identity is at the heart of a recent debate. -

INSTITUTES of the CHRISTIAN RELIGION VOL. 1 Translated by Ford Lewis Battles

THE AGES DIGITAL LIBRARY THEOLOGY INSTITUTES OF THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION VOL. 1 Translated by Ford Lewis Battles Used by permission from The Westminster Press All Rights Reserved B o o k s F o r Th e A g e s AGES Software • Albany, OR USA Version 1.0 © 1998 2 JOHN CALVIN: INSTITUTES OF THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION EDITED BY JOHN T. MCNEILL Auburn Professor Emeritus of Church History Union Theological Seminary New York TRANSLATED AND INDEXED BY FORD LEWIS BATTLES Philip Schaff Professor of Church History The Hartford Theological Seminary Hartford, Connecticut in collaboration with the editor and a committee of advisers Philadelphia 3 GENERAL EDITORS’ PREFACE The Christian Church possesses in its literature an abundant and incomparable treasure. But it is an inheritance that must be reclaimed by each generation. THE LIBRARY OF CHRISTIAN CLASSICS is designed to present in the English language, and in twenty-six volumes of convenient size, a selection of the most indispensable Christian treatises written prior to the end of the sixteenth century. The practice of giving circulation to writings selected for superior worth or special interest was adopted at the beginning of Christian history. The canonical Scriptures were themselves a selection from a much wider literature. In the patristic era there began to appear a class of works of compilation (often designed for ready reference in controversy) of the opinions of well-reputed predecessors, and in the Middle Ages many such works were produced. These medieval anthologies actually preserve some noteworthy materials from works otherwise lost. In modern times, with the increasing inability even of those trained in universities and theological colleges to read Latin and Greek texts with ease and familiarity, the translation of selected portions of earlier Christian literature into modern languages has become more necessary than ever; while the wide range of distinguished books written in vernaculars such as English makes selection there also needful. -

The History of Christian Theology Parts I–III

The History of Christian Theology Parts I–III Phillip Cary, Ph.D. PUBLISHED BY: THE TEACHING COMPANY 4840 Westfields Boulevard, Suite 500 Chantilly, Virginia 20151-2299 1-800-TEACH-12 Fax—703-378-3819 www.teach12.com Copyright © The Teaching Company, 2008 Printed in the United States of America This book is in copyright. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of The Teaching Company. Scripture quotations are from Professor Cary’s own translations and from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version ®, Copyright © 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Phillip Cary, Ph.D. Professor of Philosophy, Eastern University Professor Phillip Cary is Director of the Philosophy Program at Eastern University in St. Davids, Pennsylvania, where he is also Scholar-in- Residence at the Templeton Honors College. He earned his B.A. in both English Literature and Philosophy at Washington University in St. Louis, then earned an M.A. in Philosophy and a Ph.D. in both Philosophy and Religious Studies at Yale University. Professor Cary has taught at Yale University, the University of Hartford, the University of Connecticut, and Villanova University. He was an Arthur J. Ennis Post-Doctoral Fellow at Villanova University, where he taught in Villanova’s nationally acclaimed Core Humanities program. At Eastern University, he is a recent winner of the Lindback Award for excellence in undergraduate teaching. -

The Fitness of Scripture: Richard Chenevix Trench and Victorian Doctrines of Scripture

The Fitness of Scripture: Richard Chenevix Trench and Victorian Doctrines of Scripture by Cole William Hartin A Doctoral Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Wycliffe College and the Graduate Centre for Theological Studies of the Toronto School of Theology. In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theological Studies awarded by Wycliffe College and the University of Toronto. © Copyright by Cole William Hartin 2019 The Fitness of Scripture: Richard Chenevix Trench and Victorian Doctrines of Scripture Cole William Hartin Doctor of Philosophy in Theological Studies Wycliffe College and the University of Toronto 2019 Abstract This thesis outlines Archbishop Richard Chenevix Trench’s theology of Scripture, showing that he reads the Bible distinctively by situating him within the broader Victorian Church of England. Furthermore, it argues that because of the clarity with which Trench apprehends the character of Scripture and the interpretive implications of this, he offers a comprehensive paradigm from which one can articulate a coherent understanding of “the fitness of Holy Scripture for unfolding the spiritual life of men.” I examine Trench’s theology of Scripture by way of comparison with other prominent thinkers in the Church of England during his time. First, Charles Simeon’s devout but unidimensional interpretation, which aims to discover the full range of biblical teaching, is set beside Trench’s layered Christological reading of the text. The next chapter discusses Benjamin Jowett’s attempts to uncover the original meaning and context of each passage of Scripture. Trench’s doctrine of the Holy Spirit’s authorship juxtaposes with Jowett, opening room for a further future unfolding of the meaning inherent in Scripture. -

ABSTRACT Toward a Protestant Theology of Celibacy: Protestant Thought in Dialogue with John Paul II's Theology of the Body Ru

ABSTRACT Toward a Protestant Theology of Celibacy: Protestant Thought in Dialogue with John Paul II’s Theology of the Body Russell Joseph Hobbs, M.A., D.Min. Mentor: Ralph C. Wood, Ph.D. This dissertation examines the theology of celibacy found both in John Paul II’s writings and in current Protestant theology, with the aim of developing a framework and legitimation for a richer Protestant theology of celibacy. Chapter 1 introduces the thesis. Chapter 2 reviews the Protestant literature on celibacy under two headings: first, major treatments from the Protestant era, including those by Martin Luther, John Calvin, John Wesley, various Shakers, and authors from the English Reformation; second, treatments from 1950 to the present. The chapter reveals that modern Protestants have done little theological work on celibacy. Self-help literature for singles is common and often insightful, but it is rarely theological. Chapter 3 synthesizes the best contemporary Protestant thinking on celibacy under two headings: first, major treatments by Karl Barth, Max Thurian, and Stanley Grenz; second, major Protestant themes in the theology of celibacy. The fourth chapter describes the foundation of John Paul II’s theology of human sexuality and includes an overview of his life and education, an evaluation of Max Scheler’s influence, and a review of Karol Wojtyla’s Love and Responsibility and The Acting Person . Chapter 5 treats two topics. First, it describes John Paul II’s, Theology of the Body , and more particularly the section entitled “Virginity for the Sake of the Kingdom.” There he examines Jesus’ instruction in Matt 19:11-12, celibacy as vocation, the superiority of celibacy to marriage, celibacy as redemption of the body, Paul’s instructions in 1 Cor 7, and virginity as human destiny. -

A History of Seventh-Day Adventist Views on Biblical and Prophetic Inspiration (1844-2000)

Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 10/1-2 (1999): 486Ð542. Article copyright © 2000 by Alberto R. Timm. A History of Seventh-day Adventist Views on Biblical and Prophetic Inspiration (1844Ð2000) Alberto R. Timm Director, Brazilian Ellen G. White Research Center Brazil Adventist UniversityÐCampus 2 Introduction Seventh-day Adventists form a modern eschatological movement born out of the study of the Holy Scriptures, with the specific mission of proclaiming the Word of God Òto every nation and tribe and tongue and peopleÓ (Rev 14:6, RSV). In many places around the world Seventh-day Adventists have actually been known as the Òpeople of the Book.Ó As a people Adventists have always heldÑand presently holdÑhigh respect for the authority of the Bible. However, at times in the denominationÕs history different views on the nature of the Bi- bleÕs inspiration have been discussed within its ranks. The present study provides a general chronological overview of those major trends and challenges that have impacted on the development of the Seventh-day Adventist understanding of inspiration between 1844 and 2000. An Òannotated bibliographyÓ type of approach is followed to provide an overall idea of the subject and to facilitate further investigations of a more thematic nature. The Adventist understanding of inspiration as related to both the Bible and the writings of Ellen White is considered for two evident reasons: (1) While their basic function differs, Adventists have generally assumed that both sets of writings were produced by the same modus operandi of inspiration, and (2) there is an organic overlapping of the views on each in the development of an understanding of the BibleÕs inspiration.