Wesleyan Theological Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Must Satan Be Released? Indeed He Must Be: Toward a Biblical Understanding of Revelation 20:3 Gregory H

Volume 25, Number 1 • Spring 2014 Must Satan Be Released? Indeed He Must Be: Toward a Biblical Understanding of Revelation 20:3 Gregory H. Harris Regaining Our Focus: A Response to the Social Action Trend in Evangelical Missions Joel James and Brian Biedebach The Seed of Abraham: A Theological Analysis of Galatians 3 and Its Implications for Israel Michael Riccardi A Review of Five Views on Biblical Inerrancy Norman L. Geisler THE MASTER’S SEMINARY JOURNAL published by THE MASTER’S SEMINARY John MacArthur, President Richard L. Mayhue, Executive Vice-President and Dean Edited for the Faculty: William D. Barrick John MacArthur Irvin A. Busenitz Richard L. Mayhue Nathan A. Busenitz Alex D. Montoya Keith H. Essex James Mook F. David Farnell Bryan J. Murphy Paul W. Felix Kelly T. Osborne Michael A. Grisanti Dennis M. Swanson Gregory H. Harris Michael J. Vlach Matthew W. Waymeyer by Richard L. Mayhue, Editor Michael J. Vlach, Executive Editor Dennis M. Swanson, Book Review Editor Garry D. Knussman, Editorial Consultant The views represented herein are not necessarily endorsed by The Master’s Seminary, its administration, or its faculty. The Master’s Seminary Journal (MSJ) is is published semiannually each spring and fall. Beginning with the May 2013 issue, MSJ is distributed electronically for free. Requests to MSJ and email address changes should be addressed to [email protected]. Articles, general correspondence, and policy questions should be directed to Dr. Michael J. Vlach. Book reviews should be sent to Dr. Dennis M. Swanson. The Master’s Seminary Journal 13248 Roscoe Blvd., Sun Valley, CA 91352 The Master’s Seminary Journal is indexed in Elenchus Bibliographicus Biblicus of Biblica; Christian Periodical Index; and Guide to Social Science & Religion in Periodical Literature. -

Week 4: Jesus Christ and Human Existence • 1

Week 4: Jesus Christ and human existence • 1. Rudolf Bultmann (1884-1976) • R.B., Jesus and the Word, 1926 (ET: 1952) • R.B., The Gospel of John. A Commentary, 1941 (ET: 1971) • D. Ford (ed.), Modern Theologians, ch. on Bultmann • J.F. Kay, Christus praesens. A Reconsideration of Bultmann’s Christology, Grand Rapids 1994 Bultmann II • At the same time NT scholar and systematic theologian. • Exegetically under the influence of Wrede’s ‘radical scepticism’: • Jesus existed historically, but we have no knowledge of his personality. • We do know his teaching, the kerygma. Bultmann III • ‘I never felt uncomfortable in my critical radicalism, indeed I have been quite comfortable with it. … I let it burn, for I see that what is burning are all the fanciful notions of the Life-of-Jesus theology, and that it is the Christos kata sarka himself.’ • Cf. Paul’s dichotomies: ‘according to the flesh’ – ‘according to the spirit’ etc. • Interest in ‘human’ Jesus is no more relevant than that in other human beings. Bultmann III • Important about Jesus is his Word which at once exposes the wrongness of our existence and points a way out of it (sin – forgiveness of sins). • This happens through faith which as in Kierkegaard is miraculous. • NT witnesses this faith of the early Christians → the one miracle that matters. Bultmann IV • Bultmann’ consequence from radical dichotomy God – World is radically different from Barth’s: • Theology can only study the human response to the Word of God. • For Barth this meant moving back to ‘liberal theology’. • Bultmann saw maintaining divine transcendence as central. -

Rudolf Bultmann's Demythologizing of the New Testament

RUDOLF BULTMANN'S DEMYTHOLOGIZING OF THE NEW TESTAMENT A theological debate of major importance was begun in 1941 by Rudolf Bultmann's conference "Neues Testament und Mythologie," and for almost twenty years it has been carried on by theologians, exegetes, and philosophers of the most diverse backgrounds and convictions. The five volumes edited by Hans Werner Bartsch under the title Kerygma und Mythos,1 a collection containing the conference of Bultmann, and many of the contributions to the debate from Bultmann himself and others, are evidence of the interest which has been aroused. It is gratifying that Catholic scholars have taken their part; the fifth volume of Kerygma und Mythos is made up of some of their discussions of the problem. One finds there the names of Karl Adam, R. Schnackenburg, J. de Fraine, and J. Hâmer, among others. The fullest treatments given thus far by Catholics are Leopold Malevez's Le Message Chrétien et le Mythe,2 and Rene Marlé's Bültmann et l'Interprétation du Nouveau Testament? Among the works in English which should be specially mentioned are Reginald Fuller's Kerygma and Myth? a translation of much of the first volume of Kerygma und Mythos, and a small part of the second, together with an essay by the Eng- lish theologian, Austin Farrer; also, Ian Henderson's Myth in the New Testament.B The essay of Amos Wilder, "Mythology and New Testament,"6 and that of Kendrick Grobel, "Bultmann's Problem of New Testament 'Mythology' " 7 are of interest, since both were 1 Hamburg: Vol. I, 2 ed., 19S1; II, 1952; III, 1954; IV, 1955; V, 1955. -

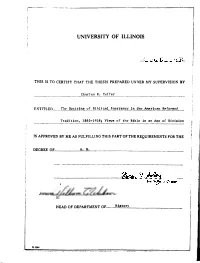

University of Illinois

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THIS tS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Charles K. Telfer ENTITLED......... The Doctrine oM bHcal.. T nerrancy. i nt ^ R? foiled Tradition, 1865-19185 Views of the Bible in an Arc of Division IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF............................. ............................................................................................................................ HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF. OII64 THE DOCTRINE OF BIBLICAL INERRANCY IN THE AMERICAN REFORMED TRADITION, 1865-1918 VIEWS OF THE BIBLE IN AN AGE OF DIVISION BY CHARLES K. TELFER THESIS for the DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS IN LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES College of Liberal Arts and Sciences University of Illinois Urbana, Illinois 1985 I. Introduction There is an increasing unanimity of opinion among historians of America’s cultural, intellectual, and religious history that the years between 1865 and 1935 form a distinct ’’epoch” or ’’period.” A number of important books published in recent years reflect this conception. Lefferts Loetscher in his masterly work on the Presbyterian Church entitled The Broadening Church (1954) deals with the years 1864 to 1936. In I960, George Marsden produced Fundamentalism and American Cultures The Shaping of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism, 1870-1925. In The Divided Mind of Protestant Amerlcat 1880-1930 (1982), Ferenc Szasz view9 these years as a distinct period in this country’s religious history.1 The years 1865 to 1935 may be typified as an ”age of division” for the American Protestant church. The church as a whole and particular denominations were rift by conflicts over important matters into ’’liberal” and ’’conservative” camps. Of course, the most well-known battles between ’’liberals” and ’’conservatives” took place in the twenties during the Modernist-Fundamentalist Controversy. -

Theological Criticism of the Bible

Currents FOCUS Reformation Heritage and the Question of Sachkritik: Theological Criticism of the Bible Paul E. Capetz Professor of Historical Theology United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities New Brighton, Minnesota new era in Protestant theology was inaugurated with the publication of Karl Barth’s ground-breaking commentary ince Bultmann was a Lutheran on Paul’s Epistle to the Romans (1919, 1922).1 This his- Atorical judgment is in keeping with the impact that Barth himself Swhereas Barth was a Calvinist, their hoped the book would have on his contemporaries. Negatively, debate in the matter of Sachkritik can he intended it to signal a break with the regnant historical-critical method of biblical exegesis (“historicism”) that had characterized be viewed as a modern reprise of the liberal Protestant theology in the nineteenth century. Positively, he aspired to recover the sort of “theological exegesis” of Scrip- earlier difference between Luther and ture exemplified by Luther and Calvin in the sixteenth century. Calvin. Distinctively twentieth-century Protestant theology thus began with Barth’s critique of one approach to biblical exegesis coupled with his call for retrieval of another approach. Both critique and mann perceived an inconsistency in Barth’s practice, since Barth retrieval stood in the service of his overriding concern to make had opened the door to Sachkritik in his Romans commentary the Bible central again to the preaching and theology of his own (even if he himself refused to walk through it, a point to which day much as it had been to that of the Reformers. Bultmann drew attention in his review). -

Luther and Beauty MARK MATTES

Word & World Volume 39, Number 1 Winter 2019 Luther and Beauty MARK MATTES heological aesthetics is not a pressing concern for most working pastors. But given that theological aesthetics is the theory of beauty in relation to God and howT the senses contribute to matters of faith, we see that working pastors, in their decisions about worship, do aesthetics far more than they may realize. Choices about music, images, worship space, and other artistic and liturgical matters quickly involve worship leaders in matters of beauty. Such decisions are important. Many who come to faith do so because faith is often something that is more caught than taught. That is, many find themselves attracted to the Christian faith, at least initially, less because it rings true to the intellect or fosters just social relations, and more because it grabs one’s attention, puzzles or strikes one with awe and wonder, and even leaves one speechless with how its story is presented in music, architec- ture, and passionate worship and preaching. Luther as Resource for Aesthetics? Most Lutherans are aware that they have a rich heritage in music and architecture. But it would seem that this heritage has developed almost in spite of Lutheran theologians, many of whom often assume that Protestantism has little to offer for a theory of beauty. This is because Protestants seem to favor words but not images, Following some twentieth-century scholars, it is often held that Martin Luther’s theology eliminates concerns about aesthetics and beauty from the Christian life and theology. But a detailed reading of Luther’s writings suggest that this is certainly not true, and that he in fact has a robust appreciation for how these elements are crucial to the Christian faith. -

65.Third Space

0IKVERHForeign Law in the Third Space *SVIMKR0E[MRXLI8LMVH7TEGI Pierre Legrand In this text, I explore a central protocol governing the articulation of knowledge within the field of comparative legal studies. Specifically, I focus on the fabrication of the ‘in- terface’ allowing the comparatist to structure his interaction with the foreign laws with which he desires to engage after having forged the view (readily stigmatized by formal- ists) that they could hold a significant and indeed crucial measure of intellectual and normative relevance for academics, lawyers, and judges operating locally – not, to be sure, as binding law, but either as apposite information or persuasive authority.1 I find it important to mention that the perpetration of the ‘interface’ by the comparatist inter- venes against his constant appreciation that no law can be re-presented except through the mediation of indicative signifiers and therefore against his ‘construction’ or, more accurately, his ‘invention’ of foreign law. (Etymologically, ‘invention’ helpfully attests to the fact that the comparatist at once finds and creates foreign law, that he simultane- ously discovers and configures it. In effect, what the comparatist names ‘foreign law’ in his report is what he inscribes as such, in words that he himself chooses and sentences that he himself crafts, having garnered ‘data’ from his necessarily selective aggregation out of the published information, his inevitably partial apprehension out of the amassed documentation, and his inescapably differential understanding out of the analyzed pas- sages.2 In the process, the comparatist readily depends on the views of individuals whom he is willing to regard as local experts – although it is far from clear how he judges a local author to be a reliable repository of knowledge in an area in which he himself, being from elsewhere, often cannot act as an authoritative source. -

German Protestant Theology Edited by Jon Stewart, University of Copenhagen, Denmark

Now available from Ashgate Publishing… Volume 10, Tome I: Kierkegaard’s Influence on Theology – German Protestant Theology Edited by Jon Stewart, University of Copenhagen, Denmark Kierkegaard Research: Sources, Reception and Resources Tome I is dedicated to the reception of Kierkegaard among German Contents: Preface; Karl Barth: the dialectic of attraction and Protestant theologians and religious thinkers. The writings of some repulsion, Lee C. Barrett; Dietrich Bonhoeffer: standing ‘in the of these figures turned out to be instrumental for Kierkegaard’s tradition of Paul, Luther, Kierkegaard, in the tradition of genuine breakthrough internationally shortly after the turn of the twentieth Christian thinking’, Christiane Tietz; Emil Brunner: polemically century. Leading figures of the movement of “dialectical promoting Kierkegaard’s Christian philosophy of encounter, theology” such as Karl Barth, Emil Brunner, Paul Tillich and Rudolf Curtis L. Thompson; Rudolf Bultmann: faith, love and self- Bultmann spawned a steadily growing awareness of and interest understanding, Heiko Schulz; Gerhard Ebeling: appreciation and in Kierkegaard’s thought among generations of German theology critical appropriation of Kierkegaard, Derek R. Nelson; Emanuel students. Emanuel Hirsch was greatly influenced by Kierkegaard Hirsch: a Germanic dialogue with ‘Saint Søren’, Matthias Wilke; and proved instrumental in disseminating his thought by producing Jurgen Moltmann: taking a moment for Trinitarian eschatology, the first complete German edition of Kierkegaard’s published works. Curtis L. Thompson; Franz Overbeck: Kierkegaard and the decay Both Barth and Hirsch established unique ways of reading and of Christianity, David R. Law; Wolfhart Pannenberg: Kierkegaard’s appropriating Kierkegaard, which to a certain degree determined the anthropology tantalizing public theology’s reasoning hope, direction and course of Kierkegaard studies right up to our own times. -

A Critical Review of Some Contemporary Existentialists in the Issue of Relationship Between Religion and Science

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 7 No 3 S1 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy May 2016 A Critical Review of Some Contemporary Existentialists in the Issue of Relationship between Religion and Science Ali Almasi1 Seyyed Mohammad Musavi Moqaddam2,* Shima Mahmudpur Qamsar3 1Ph. D. of Islamic Studies Course, International Institute of Islamic Studies of Qom, Iran 2Hadith and Qur’anic Sciences Department, University of Tehran, Iran. * Corresponding author 3M. A. Student of Hadith and Qur’anic Sciences Course, University of Tehran, Iran Doi:10.5901/mjss.2016.v7n3s1p516 Abstract In the issue of relationship between religion and science, there are some different approaches that –according to the view of Ian Barbour- include: 1.conflict, 2. Independence, 3. Integration, and 4. Dialogue. Also the approach of independence contains some points of views such as the view of Galileo, Kant and Wittgenstein. In this regard, we can count the view of existentialists -who believe in distinguish of the method and goal of religion and science, as one of the views of independence. In current study, we are trying to introduce the view of three main theist existentialists about their vantage point in the relationship between religion and science and also to explain what is the mechanism that they reach to the distinction in the method and goal of religion and science? In that case, here are mentioned Soren Kierkegaard, Martin Buber and Rudolf Bultmann. But this is not the end of the story and finally there will be present some criticisms about their view. Also it is mentionable that one of the advantages of these critiques is relates to the combination of Muslim philosophers and the westerns. -

A Study of the Idea of the VERBAL INSPIRATION OP the SCRIPTURES

A Study of the Idea of THE VERBAL INSPIRATION OP THE SCRIPTURES with special reference to. the Reformers and Post-Reformation Thinkers of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Divinity of the University of Edinburgh in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Ph.D. degree. Allan Andrew Zaun, B.A., B.D- May 15,1937 PREFACE. At the outset of this study it will be well to define terms. By "verbal Inspiration11 we mean the theory which main tains that in the process of recording the Scriptures, the Holy Spirit Himself selected the very words which the writers used. In the same sense that Milton is the author of Paradise Lost, the Holy Spirit is held to be the author of Scripture. Whether communicated by suggestion or actual dictation, the words of the text are the exact words, and no other, which God wished to have employed. The form, as well as the content, is liter ally given by Gk>d. This, briefly, is the verbal theory. We recognize the intimate, but not absolutely inseparable, con nection between thought and language. To the extent that words can be an adequate expression of the thought, Inspiration is verbal; however, the classic formulation of the doctrine, in its insistence upon dictation and verbal inerrancy, introduced mechanical features with which many scholars today cannot find themselves in full agreement. In the Reformation and post-Reformation periods we are confining our study principally to the dogmaticians of Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands; nq attempt has been made to trace the development of the doctrine in England and Scotland, which, however, were profoundly influenced by the Genevan Reformation. -

Why Resurrection?

Why Resurrection? Why Resurrection? An Introduction to the Belief in the Afterlife in Judaism and Christianity Carlos Blanco WHY RESURRECTION? An Introduction to the Belief in the Afterlife in Judaism and Christianity Copyright © 2011 Carlos Blanco. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical publications or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any man- ner without prior written permission from the publisher. Write: Permissions, Wipf and Stock Publishers, 199 W. 8th Ave., Suite 3, Eugene, OR 97401. Scripture taken from the New King James Version®. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Pickwick Publications An Imprint of Wipf and Stock Publishers 199 W. 8th Ave., Suite 3 Eugene, OR 97401 www.wipfandstock.com isbn 13: 978-1-60899-772-5 Cataloging-in-Publication data: Blanco, Carlos. Why resurrection? : an introduction to the belief in the afterlife in Judaism and Christianity / Carlos Blanco. xvi + 226 p. ; 23 cm. Including bibliographical references and index. isbn 13: 978-1-60899-772-5 1. Resurrection (Jewish Theology). 2. Resurrection—History of Doctrines—Early Church, ca. 30–600. I. Title. bt872 .b66 2011 Manufactured in the U.S.A. Contents Acknowledgments • vii List of Abbreviations • viii Introduction • ix 1 Theodicy: Philosophy of Religion and the Problem of Evil • 1 2 History and Meaning • 45 3 The Apocalyptic Conception of History, Evil, and Eschatology • 76 4 Death • 137 5 The Kingdom of God • 182 Bibliography • 217 Acknowledgments his book would not have been possible without the help of Tmany people from whose teaching and direct advice I have greatly profited. -

INSTITUTES of the CHRISTIAN RELIGION VOL. 1 Translated by Ford Lewis Battles

THE AGES DIGITAL LIBRARY THEOLOGY INSTITUTES OF THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION VOL. 1 Translated by Ford Lewis Battles Used by permission from The Westminster Press All Rights Reserved B o o k s F o r Th e A g e s AGES Software • Albany, OR USA Version 1.0 © 1998 2 JOHN CALVIN: INSTITUTES OF THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION EDITED BY JOHN T. MCNEILL Auburn Professor Emeritus of Church History Union Theological Seminary New York TRANSLATED AND INDEXED BY FORD LEWIS BATTLES Philip Schaff Professor of Church History The Hartford Theological Seminary Hartford, Connecticut in collaboration with the editor and a committee of advisers Philadelphia 3 GENERAL EDITORS’ PREFACE The Christian Church possesses in its literature an abundant and incomparable treasure. But it is an inheritance that must be reclaimed by each generation. THE LIBRARY OF CHRISTIAN CLASSICS is designed to present in the English language, and in twenty-six volumes of convenient size, a selection of the most indispensable Christian treatises written prior to the end of the sixteenth century. The practice of giving circulation to writings selected for superior worth or special interest was adopted at the beginning of Christian history. The canonical Scriptures were themselves a selection from a much wider literature. In the patristic era there began to appear a class of works of compilation (often designed for ready reference in controversy) of the opinions of well-reputed predecessors, and in the Middle Ages many such works were produced. These medieval anthologies actually preserve some noteworthy materials from works otherwise lost. In modern times, with the increasing inability even of those trained in universities and theological colleges to read Latin and Greek texts with ease and familiarity, the translation of selected portions of earlier Christian literature into modern languages has become more necessary than ever; while the wide range of distinguished books written in vernaculars such as English makes selection there also needful.