A Historical and Semantic Analysis of Methods of Biblical Interpretation As They Relate to Views of Inspiration Mildred Bangs Wynkoop Olivet Nazarene University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Must Satan Be Released? Indeed He Must Be: Toward a Biblical Understanding of Revelation 20:3 Gregory H

Volume 25, Number 1 • Spring 2014 Must Satan Be Released? Indeed He Must Be: Toward a Biblical Understanding of Revelation 20:3 Gregory H. Harris Regaining Our Focus: A Response to the Social Action Trend in Evangelical Missions Joel James and Brian Biedebach The Seed of Abraham: A Theological Analysis of Galatians 3 and Its Implications for Israel Michael Riccardi A Review of Five Views on Biblical Inerrancy Norman L. Geisler THE MASTER’S SEMINARY JOURNAL published by THE MASTER’S SEMINARY John MacArthur, President Richard L. Mayhue, Executive Vice-President and Dean Edited for the Faculty: William D. Barrick John MacArthur Irvin A. Busenitz Richard L. Mayhue Nathan A. Busenitz Alex D. Montoya Keith H. Essex James Mook F. David Farnell Bryan J. Murphy Paul W. Felix Kelly T. Osborne Michael A. Grisanti Dennis M. Swanson Gregory H. Harris Michael J. Vlach Matthew W. Waymeyer by Richard L. Mayhue, Editor Michael J. Vlach, Executive Editor Dennis M. Swanson, Book Review Editor Garry D. Knussman, Editorial Consultant The views represented herein are not necessarily endorsed by The Master’s Seminary, its administration, or its faculty. The Master’s Seminary Journal (MSJ) is is published semiannually each spring and fall. Beginning with the May 2013 issue, MSJ is distributed electronically for free. Requests to MSJ and email address changes should be addressed to [email protected]. Articles, general correspondence, and policy questions should be directed to Dr. Michael J. Vlach. Book reviews should be sent to Dr. Dennis M. Swanson. The Master’s Seminary Journal 13248 Roscoe Blvd., Sun Valley, CA 91352 The Master’s Seminary Journal is indexed in Elenchus Bibliographicus Biblicus of Biblica; Christian Periodical Index; and Guide to Social Science & Religion in Periodical Literature. -

Logos Catalog

ID Name Picture bhstcmot Bible History Commentary: Old Testament $45.50 Excellent tool for teachers - elementary, Sunday school, vacation Bible school, Bible class--and students. Franzmann clarifies historical accounts, explains difficult passages, offers essential background information, warns about misapplications of the biblical narrative, and reminds readers of the gospel. Contains maps, illustrated charts and tables, a Hebrew calendar, indexes of proper names and Scripture references, and an explanation of biblical chronology. The mission of Northwestern Publishing House is to deliver biblically sound Christ- centered resources within the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod and beyond. The vision of Northwestern Publishing House is to be the premier resource for quality Lutheran materials faithful to the Scriptures and Lutheran confessions. NPH publishes materials for worship, vacation Bible school, Sunday school, and several other ministries. The NPH headquarters are located in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. BHSWTS42 Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS Hebrew): With Westminster $99.95 4.2 Morphology This edition of the complete Hebrew Bible is a reproduction of the Michigan-Claremont-Westminster text (MCWT) with Westminster Morphology (WM, version 4.2, 2004). The MCWT is based closely on the 1983 edition of Biblica Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS). As of version 2.0, however, MCWT introduced differences between the editions, based on new readings of Codex Leningradensis b19A (L). The MCWT was collated both computationally and manually against various other texts, including Kittel's Biblia Hebraica (BHK), the Michigan-Claremont electronic text. Additionally, manual collations were made using Aron Dotan's The Holy Scriptures and BHK. The Westiminster morphological database adds a complete morphological analysis for each word/morpheme of the Hebrew text. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Achebe, Chinua. "An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's Heart if Darkness." In Hopes and Impediments, Selected ESSIDIS, 1965-1987 (Portsmouth: Heinemann, 1988) 1-13. ~~-. Moming Yet on Creation DIDI: EsslDIs (Garden City: Anchor, 1975). Achtemeier, Paul J. "'And He Followed Him': Miracles and Discipleship in Mark 10:46-52." Semeia II (1978) 115-145. Adam, A. K. M. What Is Postmodem Biblical Criticism? (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1995). Adorno, Theodor W. Minima Moralia: Riflections )Tom Damaged Lift, trans. E. F. N. Jephcott (London: New Left Books, 1974). Aichele, George. 'Jesus' Frankness." Semeia 69-70 (1995) 261-280. Aichele, George and Gary A. Phillips, eds. Intertextuality and the Bible. Semeia 69-70 (1995). ~~-. "Introduction: Exegesis, Eisegesis, Intergesis." Semeia 69-70 (1995) 7-18. Alter, Robert. The Art if Biblical Narratives (New York: Basic, 1981). Althusser, Louis. "Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes Towards an Investigation)." In Lenin and Philosophy and Other EsslDls, trans. Ben Brewster (New York: Monthly Review, 1971) 121-173. Anzaldua, Gloria. Borderlmuls/ La Frontera: The New Mestiza. (San Francisco: Spinsters/Aunt Lute, 1987). Appiah, Kwame Anthony. "Is the Post- in Postmodemism the Post- in Postcolonial?" Critical Inquiry 17 (1991) 336-357. ~~-. "Tolerable Falsehoods: Agency and the Interests of Theory." In Arac and Johnson, 63-90. Arac, Jonathan and Barbara Johnson, eds. Consequences if Theory (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991). Armstrong, Nancy. "The Occidental Alice." Differences 2 (1990) 3-40. Ashcroft, Bill, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin. The Empire Writes Back: Theory and Practice in Post-Colonial Literatures (New York: Routledge, 1989). Ba, A. Hampate. "The Living Tradition." In General History if Afiica. -

PRESBYTERIANISM in AMERICA the 20 Century

WRS Journal 13:2 (August 2006) 26-43 PRESBYTERIANISM IN AMERICA The 20th Century John A. Battle The final third century of Presbyterianism in America has witnessed the collapse of the mainline Presbyterian churches into liberalism and decline, the emergence of a number of smaller, conservative denominations and agencies, and a renewed interest in Reformed theology throughout the evangelical world. The history of Presbyterianism in the twentieth century is very complex, with certain themes running through the entire century along with new and radical developments. Looking back over the last hundred years from a biblical perspective, one can see three major periods, characterized by different stages of development or decline. The entire period begins with the Presbyterian Church being overwhelmingly conservative, and united theologically, and ends with the same church being largely liberal and fragmented, with several conservative defections. I have chosen two dates during the century as marking these watershed changes in the Presbyterian Church: (1) the issuing of the 1934 mandate requiring J. Gresham Machen and others to support the church’s official Board of Foreign Missions, and (2) the adoption of the Confession of 1967. The Presbyterian Church moves to a new gospel (1900-1934) At the beginning of the century When the twentieth century opened, the Presbyterians in America were largely contained in the Presbyterian Church U.S.A. (PCUSA, the Northern church) and the Presbyterian Church in the U.S. (PCUS, the Southern church). There were a few smaller Presbyterian denominations, such as the pro-Arminian Cumberland Presbyterian Church and several Scottish Presbyterian bodies, including the United Presbyterian Church of North America and various other branches of the older Associate and Reformed Presbyteries and Synods. -

The Social Views of Dwight L. Moody and Their Relation to the Workingman of 1860-1900

Fort Hays State University FHSU Scholars Repository Fort Hays Studies Series 1969 The oS cial Views of Dwight L. Moody and Their Relation to the Workingman of 1860-1900 Myron Raymond Chartier Fort Hays State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.fhsu.edu/fort_hays_studies_series Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Chartier, Myron Raymond, "The ocS ial Views of Dwight L. Moody and Their Relation to the Workingman of 1860-1900" (1969). Fort Hays Studies Series. 40. https://scholars.fhsu.edu/fort_hays_studies_series/40 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by FHSU Scholars Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fort Hays Studies Series by an authorized administrator of FHSU Scholars Repository. Myron Raymond Chartier The Social Views of Dwight L. Moody and Their Relation to the Workingman of 1860-1900 fort hays studies-new series history series no. 6 august, 1969 Fort Hays Kansas State College Hays, Kansas Fort Hays Studies Committee THORNS, JOHN C., JR. MARC T. CAMPBELL, chairman STOUT, ROBERTA C. WALKER, M. V. HARTLEY, THOMAS R. Copyright 1969 by Fort Hays Kansas State College Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 77-627350 ii Myron Raymond Chartier Biographical Sketch of the Author Myron Raymond Chartier received his Bachelor of Arts degree in history from the University of Colorado in 1960. In 1963 he received his Bachelor of Divinity degree from the California Baptist Theological Seminary. While serving as Campus Minister for American Baptists at Fort Hays Kansas State College from 1963- 1968, Mr. Chartier worked on a Master of Arts degree in history and completed the degree in 1969. -

The Inspiration and Truth of Sacred Scripture

The Inspiration and Truth of Sacred Scripture The Inspiration and Truth of Sacred Scripture The Word That Comes from God and Speaks of God for the Salvation of the World Pontifical Biblical Commission Translated by Thomas Esposito, OCist, and Stephen Gregg, OCist Reviewed by Fearghus O’Fearghail Foreword by Cardinal Gerhard Ludwig Müller LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org This work was translated from the Italian, Inspirazione e Verità della Sacra Scrittura. La parola che viene da Dio e parla di Dio per salvare il mondo (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2014). Cover design by Jodi Hendrickson. Cover photo: Dreamstime. Excerpts from documents of the Second Vatican Council are from The Docu- ments of Vatican II, edited by Walter M. Abbott, SJ (New York: The America Press, 1966). Unless otherwise noted, Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Bible © 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. © 2014 by Pontifical Biblical Commission Published by Liturgical Press, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, microfiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 123456789 Library of Congress Control Number: 2014937336 ISBN: 978-0-8146-4903-9 978-0-8146-4904-6 (ebook) Table of Contents Foreword xiii General Introduction xvii I. -

Pious and Critical Scholarly Paradigms of the Pentateuch •Fl

Author Biography Spencer is a third year History major from Martinez, California. In addition, he is perusing a minor in Religious Studies. His major research interests involve the study of the Old and New Testament, as well as military history. After graduation, he hopes to take his passion and research to seminary, where he can further his study of the field and history of Biblical criticism. Morgan Pious and Critical Scholarly Paradigms of the Pentateuch — during the 19th & early 20th centuries by Spencer Morgan Abstract This paper examines the antithesis between Christian scholarship and modern higher criticism of the Pentateuch during the 19th and early 20th centuries. During the 19th century, the popularization and eventual hegemony of the Doc- umentary Hypothesis revolutionized the field of Biblical studies. Modern criti- cal scholars claimed that Moses did not write the Pentateuch (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy) during the 15th century BC, but rather it was the product of a later redaction of at least four separate documents: J, E, P, and D. Writing hundreds of years apart and long after Moses, their authors reflect not the ancient covenantal religion of Moses, but rather various periods in the evolution of Israel’s religion. The implications of the Documentary Hypothe- sis bring into question the historicity and theological validity of not only the Pen- tateuch, but also the Christian New Testament which presupposes it. The goal of this research is to identify the foundational presuppositions, conclusions, and contextual consciousness that both the modern critics and the Reformed body of Christian scholars opposing them brought to their scholarship. -

Evangelical Review of Theology

EVANGELICAL REVIEW OF THEOLOGY VOLUME 12 Volume 12 • Number 1 • January 1988 Evangelical Review of Theology Articles and book reviews original and selected from publications worldwide for an international readership for the purpose of discerning the obedience of faith GENERAL EDITOR: SUNAND SUMITHRA Published by THE PATERNOSTER PRESS for WORLD EVANGELICAL FELLOWSHIP Theological Commission p. 2 ISSN: 0144–8153 Vol. 12 No. 1 January–March 1988 Copyright © 1988 World Evangelical Fellowship Editorial Address: The Evangelical Review of Theology is published in January, April, July and October by the Paternoster Press, Paternoster House, 3 Mount Radford Crescent, Exeter, UK, EX2 4JW, on behalf of the World Evangelical Fellowship Theological Commission, 57, Norris Road, P.B. 25005, Bangalore—560 025, India. General Editor: Sunand Sumithra Assistants to the Editor: Emmanuel James and Beena Jacob Committee: (The Executive Committee of the WEF Theological Commission) Peter Kuzmič (Chairman), Michael Nazir-Ali (Vice-Chairman), Don Carson, Emilio A. Núñez C., Rolf Hille, René Daidanso, Wilson Chow Editorial Policy: The articles in the Evangelical Review of Theology are the opinions of the authors and reviewers and do not necessarily represent those of the Editor or Publisher. Subscriptions: Subscription details appear on page 96 p. 3 2 Editorial Christ, Christianity and the Church As history progresses and the historical Jesus becomes more distant, every generation has the right to (and must) question his contemporary relevance—and hence also that of Christianity and the Church. The articles and book reviews in this issue generally deal with this relevance. Of the three, of course the questions about Jesus Christ are the basic ones. -

Resurrection in Daniel 12 and Its Contribution to the Theology of the Book of Daniel

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 1996 Resurrection in Daniel 12 and its Contribution to the Theology of the Book of Daniel Artur A. Stele Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Stele, Artur A., "Resurrection in Daniel 12 and its Contribution to the Theology of the Book of Daniel" (1996). Dissertations. 148. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/148 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

The Concept of Biblical Inspiration

THE CONCEPT OF BIBLICAL INSPIRATION When the President of your Society graciously asked me to read a paper on the topic of biblical inspiration, he proposed that I review and assess the significant contributions made to it in con- temporary research, and that I suggest some areas in which work might profitably be done in the future. Accordingly, I shall simply devote the time at our disposal to these two points. With regard to the first, I believe that many new insights have been provided during the last decade by the studies of Pierre Benoit,1 Joseph Coppens,2 Karl Rahner,3 and Bernhard Brink- mann; * and I shall attempt to present their work in summary form. As regards further possible theological speculation, I wish to amplify a suggestion made recently by my colleague, the Reverend R. A. F. MacKenzie. "Since the theory of instrumental causality has been so usefully developed, and has done so much to clarify—up to a point—the divine-human collaboration in this mysterious and won- derful work, what is needed next is fuller investigation of the efficient and final causalities, which went to produce an OT or NT book." B You will have observed that, since the days of Franzelin and La- grange,6 treatises on inspiration have tended to emphasize the *Paul Synave-Pierre Benoit, La Prophétie, Éditions de la Revue des Jeunes, Paris-Tournai-Rome, 1947. Benoit has a shorter essay on inspiration in Robert-Tricot, Initiation Biblique? Paris, 1954, 6-45; for further modifi- cations of his theory, cf. "Note complémentaire sur l'inspiration," Revue Bib- lique 63 (1956) 416-422. -

Dwight L. Moody: Did You Know?

Issue 25: Dwight L. Moody: 19th c. Evangelist Dwight L. Moody: Did You Know? Moody left home at age 17 and became a shoe salesman. The first time he applied for church membership, it was denied him because he failed an oral examination on Christian doctrine. When he first came to Chicago in 1856, his goal in life was to amass a fortune of $100,000. Moody ministered to soldiers in the American Civil War. His engagement to Emma Revell was formalized by the unassuming announcement that he would no longer be free to escort other young ladies home after church meetings. Abraham Lincoln visited Moody’s Sunday school, and President Grant attended one of his revival services. He chose to use theaters and lecture halls rather than churches for his meetings. Moody’s house in Chicago burned down twice; his Chicago YMCA building burned three times. Moody raised funds for the rebuilding each time. D.L. Moody was never pastor of the church that grew out of his Sunday school work and that today bears his name. At the Chicago World’s Exhibition in 1893, in a single day, over 130,000 people attended evangelistic meetings coordinated by Moody. D.L. and his son Will survived a near-fatal accident at sea. It is estimated that Moody traveled more than one million miles and addressed more than one hundred million people during his evangelistic career. Moody’s revivals often elicited relief programs for the poor. Moody once preached on Calvary’s hill on an Easter Sunday. Moody was personally acquainted with George Muller, the orphanage founder; Lord Shaftesbury, the great social reformer; and Charles H. -

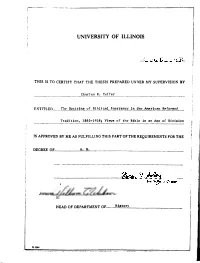

University of Illinois

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THIS tS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Charles K. Telfer ENTITLED......... The Doctrine oM bHcal.. T nerrancy. i nt ^ R? foiled Tradition, 1865-19185 Views of the Bible in an Arc of Division IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF............................. ............................................................................................................................ HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF. OII64 THE DOCTRINE OF BIBLICAL INERRANCY IN THE AMERICAN REFORMED TRADITION, 1865-1918 VIEWS OF THE BIBLE IN AN AGE OF DIVISION BY CHARLES K. TELFER THESIS for the DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS IN LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES College of Liberal Arts and Sciences University of Illinois Urbana, Illinois 1985 I. Introduction There is an increasing unanimity of opinion among historians of America’s cultural, intellectual, and religious history that the years between 1865 and 1935 form a distinct ’’epoch” or ’’period.” A number of important books published in recent years reflect this conception. Lefferts Loetscher in his masterly work on the Presbyterian Church entitled The Broadening Church (1954) deals with the years 1864 to 1936. In I960, George Marsden produced Fundamentalism and American Cultures The Shaping of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism, 1870-1925. In The Divided Mind of Protestant Amerlcat 1880-1930 (1982), Ferenc Szasz view9 these years as a distinct period in this country’s religious history.1 The years 1865 to 1935 may be typified as an ”age of division” for the American Protestant church. The church as a whole and particular denominations were rift by conflicts over important matters into ’’liberal” and ’’conservative” camps. Of course, the most well-known battles between ’’liberals” and ’’conservatives” took place in the twenties during the Modernist-Fundamentalist Controversy.