International Olympic Academy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Earnings Release 4º Quarter of 2018

Earnings Release 4º Quarter of 2018 Jundiai, March 11, 2019 - Vulcabras Azaleia S.A. (B3: VULC3) announces today its results for the fourth quarter of 2018 (3Q18). The Company’s operating and financial information is presented based on consolidated figures MENSAGEMand in millions of reais, DA prepared PRESIDÊNCIA in accordance with accounting practices adopted in Brazil and international financial reporting standards (IFRS). The data in this report refers to the performance for the forth quarter of 2018, compared to the same quarter of 2017, unless specified otherwise. HIGHLIGHTS Net Revenue: R$ 354.0 million in 4Q18, growth of 12.5.% compared to 4Q17, and R$ 1,249.0 million in 2018, down 1.1% compared to 2017. Gross Profit: R$ 133.7 milhões in 4Q18, growth of 11.7% compared to 4Q17, and R$ 448.6 million in 2018, down 7.0% compared to 2017. Gross Margin: 37.8% in 4Q18, down 0.2 p.p. in relation to 4Q17, and 35.9% in 2018, down 2.3 p.p. in relation to 2017. Net Income: R$ 46.2 million in 4Q18 vs. R$ 45.4 million in 4Q17, and R$ 152.1 million in 2018, down 19.5% compared to 2017. EBITDA: R$ 69.1 million in 4Q18 vs. R$ 70.4 million in 4Q17, and R$ 218.0 million in 2018 vs. R$ 296.5 million presented in 2017. VULC3 Quote (12/28/2018): Conference call: R$ 7.10 per share 03/12/2019 at 10 am (Brasilia time), at 9 am (New York). Number of shares Common: 245,756,346 Telephones Brazil: Market value +55 (11) 3193-1001 R$ 1.74 billion +55 (11) 2820-4001 Investor Relations IR email: [email protected] Pedro Bartelle (IRO) Vulcabras Azaleia IR Website IR Telephone: +55 (11) 5225-9500 http://vulcabrasazaleiari.com.br/ 2 MESSAGE FROM MANAGEMENT 2018 brought many difficulties, but also brought the beginning of a significant partnership for the future of Vulcabras Azaleia. -

Hommage À Marcel Trigon, Maire D'arcueil De 1964 À 1997

juillet et août 2012 | n°229 Hommage à Marcel Trigon, ‘ ‘ ‘ maire d’Arcueil de 1964 à 1997 |4 | 24 | Découvertes ‘ | 32 | C’est vous qui le dites Plus vite, | 16 Après un printemps Deux ruches au-dessus de la mairie pourri, enfin le beau temps ? plus haut, | 17 Nous exigeons ‘ Le son et lumière en photos tous un été en forme vraiment plus fort, olympique. Bientôt, des conteneurs souterrains | 20 En photo : les championnats l’été ! Tout l’été, des activités pour tous de l’Association athlétique du collège Albert-le-Grand à Arcueil ‘ o’quAI (vers 1900). d’arcueil PDF(Programme compression, complet livré avec OCR, ce numéro) web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION‘ PDFCompressor‘ PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Événement Arcueil perd un homme d’exception Par Daniel Breuiller, maire d’Arcueil Notre ville est en deuil. Elle vient de perdre Marcel fit modifier le programme de sa visite d’Etat pour venir Trigon qui fut son maire pendant 33 ans et son conseiller rendre hommage à Dulcie September à Arcueil. général durant près de 20 ans. La solidarité internationale et la lutte sociale lui tenaient Comme maire, il fut un inlassable militant de la justice à cœur : lui qui avait vu un petit camarade d’école juif sociale, du logement pour tous, de la citoyenneté active déporté et assassiné combattit toute sa vie toute forme et de la solidarité internationale. Il aimait les gens et ce de racisme, d’intolérance, ou d’exclusion. -

Vulcabras Azaleia S.A. Quarterly Financial Information September 30, 2020 Contents

Vulcabras Azaleia S.A. Quarterly financial information September 30, 2020 (A Free Translation of the original report in Portuguese as published in Brazil contain quarterly financial information prepared in accordance with accounting practices adopted in Brazil and IFRS) KPDS 743420 Vulcabras Azaleia S.A. Quarterly financial information September 30, 2020 Contents Earnings Release 3nd Quarter of 2020 2 Report on the review of quarterly information - ITR 38 Balance sheets 40 Statements of profit or loss 41 Statements of comprehensive income 42 Statement of changes in equity 43 Statements of cash flows – Indirect method 44 Statements of added value 45 Notes to the quarterly financial information 46 2 Earnings Release 3nd Quarter of 2020 Jundiaí, November 9, 2020 - Vulcabras Azaleia S.A. (B3: VULC3) (Company) announces today its results for the third quarter of 2020 (3Q30). The Company´s operating and financial information is presented based on consolidated figures and in millions of reais, prepared in accordance with accounting practices adopted in Brazil and international financial reporting standards (IFRS). The data in this report refers to the performance for the third quarter of 2020, compared to the same period of 2019, unless specified otherwise. MESSAGE FROM THE CEO HIGHLIGHTS Gross Volume: 7.9 million pairs/pieces in 3Q20, an increase of 8.6% over 3Q19, and 15.4 million pairs/pieces in 9M20, down 22.2% over 9M19. Net Revenue: R$ 382.9 million in 3Q20, an increase of 6.5% compared to 3Q19 and R$ 720.2 million in 9M20, down 27.0% over 9M19. Gross Profit: R$ 130.8 million in 3Q20, an increase of 4.8% compared to 3Q19 and R$ 234.3 million in 9M20, a reduction of 30.7% in relation to the amount recorded in 9M19. -

Building Canadian National Identity Within the State and Through Ice Hockey: a Political Analysis of the Donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 12-9-2015 12:00 AM Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893 Jordan Goldstein The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Robert K. Barney The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Jordan Goldstein 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Intellectual History Commons, Political History Commons, Political Theory Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Goldstein, Jordan, "Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3416. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3416 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Stanley’s Political Scaffold Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893 By Jordan Goldstein Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Jordan Goldstein 2015 ii Abstract The Stanley Cup elicits strong emotions related to Canadian national identity despite its association as a professional ice hockey trophy. -

Prof. Iacint Manoliu

ISSMGE Bulletin: Volume 12, Issue 4 Page 17 Obituary In Memoriam: Professor Iacint Manoliu (1934 – 2018), by TC306 Professor Iacint Manoliu passed away on June 12, 2018, at a hospital in Bucharest. He is survived by his twin sister Arina, his wife and companion (Sandra) of almost 60 years, his daughter (Mihaela), son (Costin) and grandchild (Victor). May they live a long life to remember him. And how many remarkable things they have to remember! The parents of Iacint, Alexandra and Ioan Manoliu, were professors at two of the most prestigious high schools in Bucharest. Iacint started playing sports early, together with his older sister Lia. At the beginning ping-pong on the dining table, then tennis at the Romanian Tennis Club in Bucharest. In 1948 he became the national tennis champion at the children’s category (under 15). Prior to becoming a construction engineer and teacher, Iacint Manoliu was for 12 years, between 1947 and 1959, sports journalist, editor of “Sportul Popular”, later called “Sportul”. Back row (from left to right): Alexandra and Ioan Manoliu Front row: Iacint, Arina and Lia Manoliu Iacint Manoliu obtained his Engineering (MSc) degree (1957) and PhD in Civil Engineering (1974) from the Technical University of Civil Engineering in Bucharest (UTCB). He started his academic career as a Teaching Assistant (1959–1966), then Assistant Professor (1966–1975), Associate Professor (1975–1982) and Full Professor, always at UTCB. He further served UTCB from the positions of Associate Dean (1972–1976) and Dean (1976–1984), Faculty of Civil, Industrial and Agricultural Buildings, Vice-Rector for Academic and International Affairs (1990–1996), Vice-Rector for International Affairs (1996–2000), and President of the Council for Cooperation and International Relations (2000–2011). -

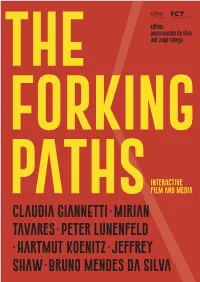

Cadavre Exquis Forking Paths from Surrealism to Interactive Film

THE FORKING PATHS – INTERACTIVE FILM AND MEDIA Editors: Bruno Mendes da Silva Jorge Manuel Neves Carrega CIAC – Centro de Investigação em Artes e Comunicação da Universidade do Algarve FCHS – Universidade do Algarve, Campus de Gambelas, 8005-139 Faro www.ciac.pt | [email protected] ISBN: 978-989-9023-53-6 ISBN (versão eletrónica): 978-989-9023-54-3 Cover: Bloco D Composition, pagination and graphic organization: Juan Manuel Escribano Loza ALL RIGHTS RESERVED FOR THE AUTHORS © 2021 Copyright by Bruno Mendes da Silva and Jorge Manuel Neves Carrega This publication is funded by national funds through the project “UIDP/04019/2020 CIAC” of the Foundation for Science and Technology. Claudia Giannetti is a researcher specialized in contemporary art, aesthetics, media art and the relation between art, science and technology. She is a theoretician, writer and exhibitions curator. For 18 years she war director of institutions and art centres in Spain, Portugal and Germany, including MECAD\ Media Centre of Art & Design (Barcelona) and the Edith- Russ-Haus for Media Art (Oldenburg, Germany). She has curated more than hundred exhibitions and cultural events in international museums. She was Professor in Spanish and Portuguese universities for the past two decades, and visiting professor and lecturer worldwide. She performs the function of adviser in several international multimedia and media art projects. Giannetti has published more than 160 articles and fifteen books in various languages, including: Ars Telemati- ca –Telecomunication, Internet and Cyberspace (Lisbon, 1998; Barcelona, 1998); Aesthetics of the Digital –Syntopy of Art, Science and Technology (Barcelona, 2002; New York/Vienna, 2004; Lisbon, 2011); The Capricious Reason in the 21st Cen- tury: The avatars of the post-industrial information society (Las Palmas, 2006); The Discreet Charm of Technology (Madrid/ Badajoz, 2008); AnArchive(s) – A Minimal Encyclopedia on Archaeology and Variantology of the Arts and Media (Olden- burg, 2014); Image and Media Ecology. -

See Partial Accord in Test Ban Talks

****** Distribution ^, W*5 t* ».. Fair U- mt mimmmm. Urn toafebt 21,350 Me. Wednesday, fair, little ) Independent Daily [ Chance in temperature. Sea \_ nonBAtTUKVoanauT-trr.mi J Wtatber, Page 2. DIAL SH I -0010 VOL. 86; NO. 12 luu.a iij, Units umofh Friday. Mcend CUn Po»t»it RED BANK, N. J., MONDAY, JULY 15, 1963 PAGE ONE Paid lUd Bank ul u AdiltteUl KtlUni Oiucuu 7c PER COPY Rockefeller Challenges Goldwater WASH»JGTON (AP)-Gov. Nel will never be found in a party son A. Rockefeller has challenged of extremism, a party of section- See Partial Accord Sen. Barry Goldwater, R-Ariz., to alism, a party of racism, a party an all-out liberal vs. conservative that disclaims responsibility for fight for the 1964 Republican pres- most of the population before it idential nomination. even starts its campaign for their In a policy statement tanta- support." mount to announcing his candi- Goldwater, who was not named dacy, the New York governor said in the statement, made no imme- In Test Ban Talks Sunday the Goldwater strategy is diate response. But associates to try to weld conservative, South- said they interpreted Rockefeller's BULLETIN ban. Underground tests were ex- North Atlantic Treaty Organiza- Western observers expected the ern and Western support while attack- as a declaration of war MOSCOW (AP) — Special empted to avoid the thorny issue tion and the Communist Warsaw opening round ol the secret three- they were certain the senator of on-site inspection. writing off Northern states. This, envoys from President Kennedy Pact alliance. He said the test ban power talks at the Kremlin would would accept, even though he re- Partial Ban and the non-aggression pact should clarify whether Khrushcfiev would Rockefeller said, "would not only and Prime Minister Macmillan main* an unannounced belliger- At the time Khrushchev ap- be signed simultaneously, but U.S.insist on the two treaties as « defeat the Republican party in opened negotiations with Pre- 1964 but would destroy it alto- ent. -

The Impact of Athletic Coaches' Ethical Behavior on Postcompetitive Athletes

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020- 2020 The Impact of Athletic Coaches' Ethical Behavior on Postcompetitive Athletes Charles Bachand University of Central Florida Part of the Sports Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd2020 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020- by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Bachand, Charles, "The Impact of Athletic Coaches' Ethical Behavior on Postcompetitive Athletes" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2020-. 324. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd2020/324 THE IMPACT OF ATHLETIC COACHES’ ETHICAL BEHAVIOR ON POST- COMPETITIVE ATHLETES by CHARLES BACHAND M.S. Sports and Exercise Science, University of Central Florida, 2015 B.S. Sports and Exercise Science, University of Central Florida, 2013 A.A. Business Administration, Keiser College, 1998 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in the Department of Learning Sciences & Educational Research in the College of Community Innovation and Education at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2020 Major Professors: Carolyn Hopp and Thomas Vitale ABSTRACT Much of the literature regarding abuse in athletics has focused on the effects these actions have on the athletes both short and long term. In relation to ethics, such research has been primarily focused on how ethics effects all aspects of athletics. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine if factors that cause coaches to victimize athletes are related to a lack of ethical understanding. -

The Rebels of 1894 and a Visionary Activist

ИСТОРИЯ Kluge V. The rebels of 1894 and a visionary activist. Science in Olympic Sport. Клюге Ф. Пьер Кубертен – дальновидный активист. Наука в олимпийском спор- 2020; 1:22-47. DOI:10.32652/olympic2020.1_2 те. 2020; 1:22-47. DOI:10.32652/olympic2020.1_2 The rebels of 1894 and a visionary activist Vollcer Kluge The rebels of 1894 and a visionary activist Vollcer Kluge АBSTRACT. The article is dedicated to Pierre de Coubertin, the French public figure and initiator of the Olympic Games re- vival. He initiated free movement of athletes, embodied the idea of peace and made a proposal to restore the Olympic Games. Coubertin couldn't remember when he thought of reviving the Olympics, but ancient Olympia had always been "a place of nostalgia" for him. However, the path to his goal realization was not easy, the sensational idea of the revival of the Olympic Games did not always find feedback, and almost no one could understand the consequences and separate the idea of Cou- bertin from ancient views of the Olympic Games. The obvious difficulties and the loss of support failed to stop the visionary aristocrat, but prompted organization of large-scale events, including the Congress of 1894, which first considered the pos- sibility of reviving the Olympic Games and the conditions for their restoration. “The project referred to in the last paragraph will rather be a pleasant expression of the international harmony to which we do not aspire, but simply envision. Restoration of the Olympic Games on the basis and in the conditions that meet the needs of modern life will gather representatives of the peoples of the world every four years, and one can think that this peaceful and polite rivalry will represent the best form of internationalism." More than once, Coubertin had to defend his idea in serious discussions, but ultimately it was agreed that the international games should be held every four years and include only amateur athletes with the exception of fencing. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

8 August 2000

INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY FOURTIETH SESSION 23 JULY - 8 AUGUST 2000 1 © 2001 International Olympic Committee Published and edited jointly by the International Olympic Committee and the International Olympic Academy 2 INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY 40TH SESSION FOR YOUNG PARTICIPANTS SPECIAL SUBJECT: OLYMPIC GAMES: ATHLETES AND SPECTATORS 23 JULY - 8 AUGUST 2000 ANCIENT OLYMPIA 3 EPHORIA (BOARD OF DIRECTORS) OF THE INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC ACADEMY President Nikos FILARETOS IOC Member Honorary life President Juan Antonio SAMARANCH IOC President 1st Vice-president George MOISSIDIS Member of the Hellenic Olympic Committee 2nd Vice-president Spiros ZANNIAS Honorary Vice-president Nikolaos YALOURIS Member ex-officio Lambis NIKOLAOU IOC Member President of the Hellenic Olympic Committee Dean Konstantinos GEORGIADIS Members Dimitris DIATHESSOPOULOS Secretary General of the Hellenic Olympic Committee Georgios YEROLIMBOS Ioannis THEODORAKOPOULOS President of the Greek Association of Sports Journalists Epaminondas KIRIAZIS Cultural Consultant Panagiotis GRAVALOS 4 IOC COMMISSION FOR CULTURE AND OLYMPIC EDUCATION President Zhenliang HE IOC member in China Vice-president Nikos FILARETOS IOC member in Greece Members Fernando Ferreira Lima BELLO IOC member in Portugal Valeriy BORZOV IOC member in Ukraine Ivan DIBOS IOC member in Peru Sinan ERDEM IOC member in Turkey Nat INDRAPANA IOC member in Thailand Carol Anne LETHEREN t IOC member in Canada Francis NYANGWESO IOC member in Uganda Lambis W. NIKOLAOU IOC member in Greece Mounir SABET IOC member in -

SEPTEMBER 2004 PAGE 1-19.Qxd

THE GREEK AUSTRALIAN The oldest circulating Greek newspaper outside Greece email: VEMA [email protected] SEPTEMBER 2004 Tel. (02) 9559 7022 Fax: (02) 9559 7033 In this issue... Our Primate’s View VANDALISM PAGE 5/23 TRAVEL: Scaling Corinth’s mythical peaks PAGE 16/34 ‘Dream Games’ The Athens 2004 Games, the 28th Olympiad of the modern effort, it provided security in the air, the sea and on land. But era, ended on August 28 with a closing ceremony that cele- in the end, it was the athletes who were at the heart of the brated 16 days of competition and the nation that had played Games, setting as they did several new world and Olympic host to the world. Athens presented the Games with state-of- records. the art venues, and, through an unprecedented multinational FULL REPORT PAGE 20-38 SEPTEMBER 2004 2/20 TO BHMA The Greek Australian VEMA Your Say Who was the Founder of the Modern Olympics? Dear Editor ancient, but not classic games, tive of establishing the modern renovation of the Panathenian I must take umbrage at your and two modern. Prizes were Olympic Games. After becoming Stadium asked him to contribute, journalist K I Angelopoulos, who both monetary and symbolical. a member of the Panhellenic Averoff stated that he would dared to repeat that pathetic non- There was a band playing an Gymnastic Society in Athens, he undertake the renovation of the sense which accords Pierre de Olympic Hymn, specially com- represented the Society in the ancient Panathenian Stadium, at Coubertain as the Founder of the posed for the occasion.