The Anarchist Press at Home, Washington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z

1111 ~~ I~ I~ II ~~ I~ II ~IIIII ~ Ii II ~III 3 2103 00341 4723 ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER A Communist's Fifty Yea1·S of ,tV orking-Class Leadership and Struggle - By Elizabeth Gurley Flynn NE'V CENTURY PUBLISIIERS ABOUT THE AUTHOR Elizabeth Gurley Flynn is a member of the National Com mitt~ of the Communist Party; U.S.A., and a veteran leader' of the American labor movement. She participated actively in the powerful struggles for the industrial unionization of the basic industries in the U.S.A. and is known to hundreds of thousands of trade unionists as one of the most tireless and dauntless fighters in the working-class movement. She is the author of numerous pamphlets including The Twelve and You and Woman's Place in the Fight for a Better World; her column, "The Life of the Party," appears each day in the Daily Worker. PubUo-hed by NEW CENTURY PUBLISH ERS, New York 3, N. Y. March, 1949 . ~ 2M. PRINTED IN U .S .A . Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER TAUNTON, ENGLAND, ·is famous for Bloody Judge Jeffrey, who hanged 134 people and banished 400 in 1685. Some home sick exiles landed on the barren coast of New England, where a namesake city was born. Taunton, Mass., has a nobler history. In 1776 it was the first place in the country where a revolutionary flag was Bown, "The red flag of Taunton that flies o'er the green," as recorded by a local poet. A century later, in 1881, in this city a child was born to a poor Irish immigrant family named Foster, who were exiles from their impoverished and enslaved homeland to New England. -

Firebrand and the Forging of a New Anarchism: Anarchist Communism and Free Love Fall 2004

The Firebrand and the Forging ofa New Anarchism: Anarchist Communism and Free Love Jessica Moran Fall 2004 Contents Firebrand and its Editors ........................... 8 What is Anarchist Communism? ...................... 12 Anarchism and Sex ............................. 15 Conclusion .................................. 19 2 In January 1895 a small paper appeared in Portland, Oregon. Titled Firebrand, and staunchly and openly advocating anarchist communism and free love, the pa- per was instrumental in the development of American anarchism. The paper sys- tematically brought working-class anarchism and social revolution to an English speaking audience for the first time, influencing the direction of anarchism inthe United States for the next twenty years. Understanding the pivotal position of Fire- brand in what is often considered a dormant period in American anarchist history, is necessary to comprehending the evolution of anarchism in the United States. The American anarchist movement thrived in the last part of the 1890s. Firebrand fos- tered the growth of an anarchist movement that incorporated the economic change fought for by the Haymarket anarchists, along with social issues like free love and individual freedom long advocated by individualist anarchists. Published between 1895 and 1897, Firebrand helped reinvigorate the anarchist movement, and intro- duced an important development that remained part of the anarchist movement throughout the twentieth century. By combining the economic and political argu- ments of anarchist communism with the social and cultural ideas of free love, Fire- brand and its contributors consciously developed an anarchism that appealed to both immigrant and native-born Americans. The anarchism discussed and worked out in the pages of Firebrand influenced and perhaps even formed the American an- archism appearing after the turn of the century, which gained popular expression throughout the Progressive Era. -

Jay Fox: the Life and Times of an American Radical

Eastern Washington University EWU Digital Commons EWU Masters Thesis Collection Student Research and Creative Works 2016 Jay Fox: the life and times of an American radical David J. Collins Eastern Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.ewu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Collins, David J., "Jay Fox: the life and times of an American radical" (2016). EWU Masters Thesis Collection. 338. https://dc.ewu.edu/theses/338 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research and Creative Works at EWU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in EWU Masters Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of EWU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JAY FOX: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF AN AMERICAN RADICAL A Thesis Presented To Eastern Washington University Cheney, Washington In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History By David J. Collins Spring 2016 ii iii iv Acknowledgements First, I have to acknowledge Ross K. Rieder who generously made his collection of Jay Fox papers available to me, as well as permission to use it for this project. Next, a huge thanks to Dr. Joseph U. Lenti who provided guidance and suggestions for improving the project, and put in countless hours editing and advising me on revisions. Dr. Robert Dean provided a solid knowledge of the time period through coursework and helped push this thesis forward. Dr. Mimi Marinucci not only volunteered her time to participate on the committee, but also provided support and guidance to me from my first year as an undergraduate at Eastern Washington University, and continues to be an influential mentor today. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5030

VOL. I—NO. 6 , APRIL, 1925 PRICE 5 CENTS The Evolution of Anarchist Theories E shall attempt to review in lence: rent, interest, profit, and taxes. The further develbpmeht of Anar this brief sketch the theoreti They demand freedom of production for chist theories therefore centered around W cal developmlent of Anar the individual and for the voluntary the problem qf harmonizing, economic chism by describing the ideas whence groups in unrestrained competition in conditions with the basic principle of Anarchist thought originated and the the open market. The principle of the a free society. The idea of equitable manner in which the various. modern "full product of one's labor" is main and direct exchange repeatedly sought schools of Anarchism gradually devel tained by securing to each, as his in practical expression, as in the London oped. We shall therefore leave out of alienable private possesMon, all that he Industrial Fairs, also in America aud consideration all general historical dis is able to gain by competing against France. Similar ideas are still cham cussions, biographic and literary data, the whole field. Thel restrictions en pioned by the American, English, and and the external history of the move forced in present society by monopoly Australian Individualist Anarchists, as ment. —aided by its^ tool, the State—^being well as by somie followers of Proudhon and Stirner. Our modern attitude, how There never lacked men to advocate eliminated, the equal opportunity of all ever, is opposed to these ideas on the subtle projects of governmental organ niust result in the equitable exchange ground that the requirements of com ization and regulation of production of equal values. -

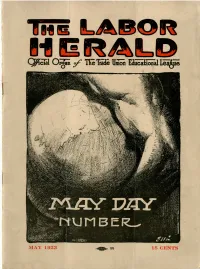

Issue No. 3, May, 1923

QP?cial Organ ?f TKe Trade Union Educational Lesli MAY 1923 99 15 GENTS JUST OFF THE PRESS The Labor Defense Council Pamphlet A masterful presentation of the background of the Michigan Criminal Syndi- calism Case, the high points of the prosecution and the defense and a clear cut statement of the issues involved. • / No one who wishes to keep informed about the development of the governmental attacks on labor can afford to miss this brilliant pamphlet;. For those who want to aid in the defense of the men and -vjromen now being pro- secuted, it is an absolute necessity. 24 pages, 6x9 inch, A permanent con- Cover design by tribution to Ameri- can Labor Litera- Fred Ellis, illustra- ture. A smashing ted with 22 pictures attack on the Labor- of the principals of baiters and their the defense and the masters, the "Cap- prosecution and of tains" of Industry- A spirited defense scenes taken at the of' the rights of Foster trial. labor. Published By LABOR DEFENSE COUNCIL 166 W. Washington St. CHICAGO, ILL. ' ' | Price 10 cents ; BUY IT! READ IT! SELL IT! Help the Michigan Defense by Putting a Copy of This Pamphlet in the Hands of Every Worker, Every Lover of Liberty. Order a Bundle to Sell at Union and Mass Meetings ~~j 10 cents a copy, '3 for 25 cents, 14 for a Enclosed please find $ ~ dollar, $6.50 per hundred. Postpaid any for _.:. copies of the place in the U. S. or Canada. Labor Defense Council pamphlet. Address all comimunications and make checks payable to, Name - LABOR DEFENSE COUNCIL I Address .~ Room 307, 166 W. -

Anarchist Periodicals in English Published in the United (1833–1955) States (1833–1955): an Annotated Guide, Ernesto A

Anarchist Periodicals REFERENCE • ANARCHIST PERIODICALS Longa in English In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, dozens of anarchist publications appeared throughout the United States despite limited fi nancial resources, a pestering and Published in censorial postal department, and persistent harassment, arrest, and imprisonment. the United States Such works energetically advocated a stateless society built upon individual liberty and voluntary cooperation. In Anarchist Periodicals in English Published in the United (1833–1955) States (1833–1955): An Annotated Guide, Ernesto A. Longa provides a glimpse into the doctrines of these publications, highlighting the articles, reports, manifestos, and creative works of anarchists and left libertarians who were dedicated to An Annotated Guide propagandizing against authoritarianism, sham democracy, wage and sex slavery, Anarchist Periodicals in English Published in the United States and racial prejudice. Nearly 100 periodicals produced throughout North America are surveyed. Entries include title; issues examined; subtitle; editor; publication information, including location and frequency of publication; contributors; features and subjects; preced- ing and succeeding titles; and an OCLC number to facilitate the identifi cation of (1833–1955) owning libraries via a WorldCat search. Excerpts from a selection of articles are provided to convey both the ideological orientation and rhetorical style of each newspaper’s editors and contributors. Finally, special attention is given to the scope of anarchist involvement in combating obscenity and labor laws that abridged the right to freely circulate reform papers through the mail, speak on street corners, and assemble in union halls. ERNESTO A. LONGA is assistant professor of law librarianship at the University of New Mexico School of Law. -

Communist) Party of America Is the Class Party of the of the Rich Farmer, Small and Medium Capitalist and the American Workers and Poor Farmers

A Good Policy— For a Workingman! £ DAILY WORKER When you make it your policy InsurancerS to protect your interests as a worker—that's a good policy. When you make it your policy to establish firmly a great work- ing class newspaper to BETTER protect your interests — that's still your policy—that's a good policy. This Policy is to Insure THE DAILY WORKER, for 1925.' Insure the Daily Worker for 1925 to build the Labor Movement to protect your interests. AND WHEN YOU GIVE— Every cent that you can spare—you will receive the DAILY WORKER Insurance Policy for the amount remitted as a token of your policy to protect the workingman's interests in the best way. The Policy in $10, $5 and $1 denominations is made in colors and has the Red Star of the world's first working class government. THIS IS YOUR POLICY—INSURE THE DAILY WORKER FOR 1925 WITH EVERY My policy is to protect working class interests—my interests. For this I enclose $ which you will acknowledge by sending me a printed policy CENT THAT to prove my statement. YOU CAN Name Street SPARE! City State.. Maurice Becker Symposium In a Cell-Leavenworth FEBRUARY, 1925 159 Teddy's Correspondence Confidential Letters of An Earlier LaFollette By Thurber Lewis HE private correspondence of Henry Cabot Lodge and That Roosevelt's anti-trust campaign was sheer bluff is T Theodore Roosevelt, the result of forty years of personal made clear by the following extract from a letter by Lodge: friendship, has been given to the press as prepared by Lodge "The country will certainly not forget your attitude toward prior to the latter's death. -

Anarchism on the Willamette: the Firebrand Newspaper and the Origins of a Culturally American Anarchist Movement, 1895-1898

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 7-6-2018 Anarchism on the Willamette: the Firebrand Newspaper and the Origins of a Culturally American Anarchist Movement, 1895-1898 Alecia Jay Giombolini Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Giombolini, Alecia Jay, "Anarchism on the Willamette: the Firebrand Newspaper and the Origins of a Culturally American Anarchist Movement, 1895-1898" (2018). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4471. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6355 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Anarchism on the Willamette: The Firebrand Newspaper and the Origins of a Culturally American Anarchist Movement, 1895-1898 by Alecia Jay Giombolini A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: Joseph Bohling, Chair Katrine Barber Catherine McNeur Cristine Paschild Portland State University 2018 © 2018 Alecia Jay Giombolini Abstract The Firebrand was an anarchist communist newspaper that was printed in Portland, Oregon from January 1895 to September 1897. The newspaper was a central catalyst behind the formation of the culturally American anarchist movement, a movement whose vital role in shaping radicalism in the United States during the Progressive Era has largely been ignored by historians. -

Labor History in the United States

imm BIBLIOGRAPHIC CONTRIBUTIONS NO. 6 LABOR HISTORY IN THE UNITED STATES A General Bibliography INSTITUTE OF LABOR AND INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LI B RARY OF THE UNIVER.5ITY.. Of ILLINOIS 0163310973 St8£ Hii/juiii tr.'jiiorty suKVfet LIBRARY BIBLIOGRAPHIC CONTRIBUTIONS NO. 6 LABOR HISTORY IN THE UNITED STATES A General Bibliography Compiled by Gene S. Stroud and Gilbert E. Donahue INSTITUTE OF LABOR AND INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS, URBANA, 1961 Manufactured in the United States of America. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. A6 1-9096. 0/<i, 33/6773 PREFACE In 1953, the University of Illinois Institute of Labor and Industrial Relations published Ralph E. McCoy's History of Labor and Unionism in the United States: A Selected Bibliography as the second in its new Bibliographic Contributions series. In the preface of that compilation of 1,024 titles. Professor McCoy stated: This contribution is largely an assemblage of secondary works published sepa- rately, i.e., books and pamphlets. Some of the items are surveys of existing conditions rather than histories, but have attained historical value with the passing of time. The term "labor" is used in a broad sense to include working conditions, labor-management relations, and government regulation of industrial relations. This broad approach to the compilation of materials on labor history as well as the bibliography itself were favorably received, and the publica- tion was soon out of print. Basic to the McCoy bibliography were standard books, monographs, and pamphlets on labor history and related accounts of specific events, movements, or organizations which influenced the development of trade unionism in the United States. -

Rocker's Anarcho-Syndicalism, After Far Too Many Years, Is an Event of Much Importance for People Who Are Concerned with Problems of Liberty and Justice

This edition first published 1989 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA and 22883 Quicksilver Drive, Sterling, VA21066-2012, USA First published 1938 by Martin Seeker and Warburg British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0 7453 1392 2 hbk Printed in the EC by Athenreum Press Ltd, Gateshead, Tyne & Wear Contents Preface NOAM CHOMSKY vi Introduction NICOLAS WALTER viii 1. Anarchism: Its Aims and Purposes 9 2. The Proletariat and the Beginning of the Modern Labour Movement 34 3. The Forerunners of Syndicalism 56 4. The Objectives of Anarcho-Syndicalism 82 5. The Methods of Anarcho-Syndicalism 109 6. The Evolution of Anarcho-Syndicalism 131 Bibliography 155 Epilogue 159 Preface NOAM CHOMSKY The publication of Rudolf Rocker's Anarcho-Syndicalism, after far too many years, is an event of much importance for people who are concerned with problems of liberty and justice. Speaking personally, I became acquainted with Rocker's publications in the early years of the Second World War, in anarchist book stores and offices in New York City, and came upon the present work on the dusty shelves of a university library, unknown and unread, a few years later. I found it an inspiration then, and have turned back to it many times in the years since. I felt at once, and still feel, that Rocker was pointing the way to a much better world, one that is within our grasp, one that may well be the only alternative to the 'universal catastrophe' towards which 'we are driving on under full sail', as he saw on the eve of the Second World War. -

The Leadership of American Communism, 1924–1929: Sketches for a Prosopographical Portrait

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk McIlroy, John and Campbell, Alan (2019) The leadership of American communism, 1924–1929: sketches for a prosopographical portrait. American Communist History . ISSN 1474-3892 [Article] (Published online first) (doi:10.1080/14743892.2019.1681200) Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/28260/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Quark 16.1.Qxd 14-05-14 11:03 AM Page 9

Quark 16_1 final_Quark 16.1.qxd 14-05-14 11:03 AM Page 9 Jay Fox: A Journey from Anarchism to Communism Greg Hall Soon after dropping out of school at the age of fourteen, Jay Fox began his working life in a Chicago cabbage patch. For fifty cents a day, he plant - ed cabbage plant seedlings in the spring and was part of the harvest later in the year. 1 The cabbage work was seasonal, so Fox drifted into other employment until he landed at job at the Mallable Iron Works in fall 1885. At the foundry, he worked in the trimming room for seventy-five cents for a ten hour day, six days a week. Sometime during those first weeks of factory employment, he joined a local assembly of the Knights of Labor. Fox continued to work steadily at the foundry until the city-wide strike of May 1, 1886. He then became a picket, which he recalled as “my first active participation in the class struggle.” 2 Out of curiosity that day, he left his workers’ picket line and went over to the picket line near the McCormick works that was just a couple of blocks away, where laborers were also on strike. Soon after he took up a spot on the line, scabs – with a con - tingent of police – arrived to break through the picket line. A melee ensued, resulting in the deaths of several striking workers and the injury to many more, including Fox who was grazed in the arm by a policeman’s bullet.