Quark 16.1.Qxd 14-05-14 11:03 AM Page 9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z

1111 ~~ I~ I~ II ~~ I~ II ~IIIII ~ Ii II ~III 3 2103 00341 4723 ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER A Communist's Fifty Yea1·S of ,tV orking-Class Leadership and Struggle - By Elizabeth Gurley Flynn NE'V CENTURY PUBLISIIERS ABOUT THE AUTHOR Elizabeth Gurley Flynn is a member of the National Com mitt~ of the Communist Party; U.S.A., and a veteran leader' of the American labor movement. She participated actively in the powerful struggles for the industrial unionization of the basic industries in the U.S.A. and is known to hundreds of thousands of trade unionists as one of the most tireless and dauntless fighters in the working-class movement. She is the author of numerous pamphlets including The Twelve and You and Woman's Place in the Fight for a Better World; her column, "The Life of the Party," appears each day in the Daily Worker. PubUo-hed by NEW CENTURY PUBLISH ERS, New York 3, N. Y. March, 1949 . ~ 2M. PRINTED IN U .S .A . Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER TAUNTON, ENGLAND, ·is famous for Bloody Judge Jeffrey, who hanged 134 people and banished 400 in 1685. Some home sick exiles landed on the barren coast of New England, where a namesake city was born. Taunton, Mass., has a nobler history. In 1776 it was the first place in the country where a revolutionary flag was Bown, "The red flag of Taunton that flies o'er the green," as recorded by a local poet. A century later, in 1881, in this city a child was born to a poor Irish immigrant family named Foster, who were exiles from their impoverished and enslaved homeland to New England. -

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: the 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike By Leigh Campbell-Hale B.A., University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1977 M.A., University of Colorado, Boulder, 2005 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado and Committee Members: Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas G. Andrews Mark Pittenger Lee Chambers Ahmed White In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History 2013 This thesis entitled: Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike written by Leigh Campbell-Hale has been approved for the Department of History Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas Andrews Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii Campbell-Hale, Leigh (Ph.D, History) Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike Dissertation directed by Associate Professor Phoebe S.K. Young This dissertation examines the causes, context, and legacies of the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike in relationship to the history of labor organizing and coalmining in both Colorado and the United States. While historians have written prolifically about the Ludlow Massacre, which took place during the 1913- 1914 Colorado coal strike led by the United Mine Workers of America, there has been a curious lack of attention to the Columbine Massacre that occurred not far away within the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike, led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). -

Firebrand and the Forging of a New Anarchism: Anarchist Communism and Free Love Fall 2004

The Firebrand and the Forging ofa New Anarchism: Anarchist Communism and Free Love Jessica Moran Fall 2004 Contents Firebrand and its Editors ........................... 8 What is Anarchist Communism? ...................... 12 Anarchism and Sex ............................. 15 Conclusion .................................. 19 2 In January 1895 a small paper appeared in Portland, Oregon. Titled Firebrand, and staunchly and openly advocating anarchist communism and free love, the pa- per was instrumental in the development of American anarchism. The paper sys- tematically brought working-class anarchism and social revolution to an English speaking audience for the first time, influencing the direction of anarchism inthe United States for the next twenty years. Understanding the pivotal position of Fire- brand in what is often considered a dormant period in American anarchist history, is necessary to comprehending the evolution of anarchism in the United States. The American anarchist movement thrived in the last part of the 1890s. Firebrand fos- tered the growth of an anarchist movement that incorporated the economic change fought for by the Haymarket anarchists, along with social issues like free love and individual freedom long advocated by individualist anarchists. Published between 1895 and 1897, Firebrand helped reinvigorate the anarchist movement, and intro- duced an important development that remained part of the anarchist movement throughout the twentieth century. By combining the economic and political argu- ments of anarchist communism with the social and cultural ideas of free love, Fire- brand and its contributors consciously developed an anarchism that appealed to both immigrant and native-born Americans. The anarchism discussed and worked out in the pages of Firebrand influenced and perhaps even formed the American an- archism appearing after the turn of the century, which gained popular expression throughout the Progressive Era. -

Jay Fox: the Life and Times of an American Radical

Eastern Washington University EWU Digital Commons EWU Masters Thesis Collection Student Research and Creative Works 2016 Jay Fox: the life and times of an American radical David J. Collins Eastern Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.ewu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Collins, David J., "Jay Fox: the life and times of an American radical" (2016). EWU Masters Thesis Collection. 338. https://dc.ewu.edu/theses/338 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research and Creative Works at EWU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in EWU Masters Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of EWU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JAY FOX: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF AN AMERICAN RADICAL A Thesis Presented To Eastern Washington University Cheney, Washington In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History By David J. Collins Spring 2016 ii iii iv Acknowledgements First, I have to acknowledge Ross K. Rieder who generously made his collection of Jay Fox papers available to me, as well as permission to use it for this project. Next, a huge thanks to Dr. Joseph U. Lenti who provided guidance and suggestions for improving the project, and put in countless hours editing and advising me on revisions. Dr. Robert Dean provided a solid knowledge of the time period through coursework and helped push this thesis forward. Dr. Mimi Marinucci not only volunteered her time to participate on the committee, but also provided support and guidance to me from my first year as an undergraduate at Eastern Washington University, and continues to be an influential mentor today. -

The Industrial Workers of the World in the Seattle General Strike - Colin M

The Industrial Workers of the World in the Seattle general strike - Colin M. Anderson An attempt to find out the IWW's actual involvement in the Seattle General Strike of 1919, which has been hampered by myths caused by the capitalist press and AFL union leaders of the time. The Seattle General Strike is an event very important in the history of the Pacific Northwest. On February 6, 1919 Seattle workers became the first workers in United States history to participate in an official general strike. Many people know little, if anything, about the strike, however. Perhaps the momentousness of the event is lost in the fact that the strike took place without violence, or perhaps it is because there was no apparent visible change in the city following the event. But the strike is a landmark for the U.S. labor movement, and is very important, if for no there reason, for what it stands for. Workers expressed their power through a massive action of solidarity, and demonstrated to the nation the potential power of organized labor. This was at a time when labor was generally divided over ideological lines that prevented them from achieving such mass action very often. For many at the time, however, the strike represented something else: something more sinister and extreme. To many of the locals in Seattle the strike was the beginning of an attempted revolution by the Industrial Workers of the World and others with similar radical tendencies. These people saw the putting down of the strike was the triumph of patriotism in the face of radicalism gone too far. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5030

VOL. I—NO. 6 , APRIL, 1925 PRICE 5 CENTS The Evolution of Anarchist Theories E shall attempt to review in lence: rent, interest, profit, and taxes. The further develbpmeht of Anar this brief sketch the theoreti They demand freedom of production for chist theories therefore centered around W cal developmlent of Anar the individual and for the voluntary the problem qf harmonizing, economic chism by describing the ideas whence groups in unrestrained competition in conditions with the basic principle of Anarchist thought originated and the the open market. The principle of the a free society. The idea of equitable manner in which the various. modern "full product of one's labor" is main and direct exchange repeatedly sought schools of Anarchism gradually devel tained by securing to each, as his in practical expression, as in the London oped. We shall therefore leave out of alienable private possesMon, all that he Industrial Fairs, also in America aud consideration all general historical dis is able to gain by competing against France. Similar ideas are still cham cussions, biographic and literary data, the whole field. Thel restrictions en pioned by the American, English, and and the external history of the move forced in present society by monopoly Australian Individualist Anarchists, as ment. —aided by its^ tool, the State—^being well as by somie followers of Proudhon and Stirner. Our modern attitude, how There never lacked men to advocate eliminated, the equal opportunity of all ever, is opposed to these ideas on the subtle projects of governmental organ niust result in the equitable exchange ground that the requirements of com ization and regulation of production of equal values. -

Issue No. 3, May, 1923

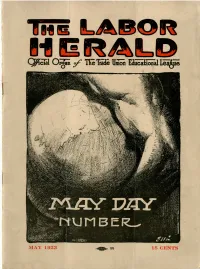

QP?cial Organ ?f TKe Trade Union Educational Lesli MAY 1923 99 15 GENTS JUST OFF THE PRESS The Labor Defense Council Pamphlet A masterful presentation of the background of the Michigan Criminal Syndi- calism Case, the high points of the prosecution and the defense and a clear cut statement of the issues involved. • / No one who wishes to keep informed about the development of the governmental attacks on labor can afford to miss this brilliant pamphlet;. For those who want to aid in the defense of the men and -vjromen now being pro- secuted, it is an absolute necessity. 24 pages, 6x9 inch, A permanent con- Cover design by tribution to Ameri- can Labor Litera- Fred Ellis, illustra- ture. A smashing ted with 22 pictures attack on the Labor- of the principals of baiters and their the defense and the masters, the "Cap- prosecution and of tains" of Industry- A spirited defense scenes taken at the of' the rights of Foster trial. labor. Published By LABOR DEFENSE COUNCIL 166 W. Washington St. CHICAGO, ILL. ' ' | Price 10 cents ; BUY IT! READ IT! SELL IT! Help the Michigan Defense by Putting a Copy of This Pamphlet in the Hands of Every Worker, Every Lover of Liberty. Order a Bundle to Sell at Union and Mass Meetings ~~j 10 cents a copy, '3 for 25 cents, 14 for a Enclosed please find $ ~ dollar, $6.50 per hundred. Postpaid any for _.:. copies of the place in the U. S. or Canada. Labor Defense Council pamphlet. Address all comimunications and make checks payable to, Name - LABOR DEFENSE COUNCIL I Address .~ Room 307, 166 W. -

The American Labor Movement in Modern History and Government Textbooks

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 789 SO 007 302 AUTHOR Sloan, Irving TITLE The American Labor Movement in Modern History and Government Textbooks. INSTITUTION American Federation of Teachers, Washington, E.C. PUB DATE [74] NOTE 53p. AVAILABLE FROM American Federation of Teachers, AFL-CIO, 1012 14th St., N. W., Washington, D. C. 20005 (Item No. 598, $0.30) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$3.15 DESCRIPTORS *American Government (Course); *Collective Bargaining; Evaluation Criteria; High School Curriculum; Industrial Relations; Labor Conditions; Labor Force; Labor Legislation; *Labor Unions; Secondary Education; Surveys; Textbook Content; *Textbook Evaluation; Textbooks; *United States History ABSTRACT A survey of nineteen American history high school texts and eight government texts attempts to discover if schools are still failing to teach adequately about labor unions, their history, procedures, and purposes. For each text a summary account is provided of what the text has to say about labor in terms of a set of pre-established criteria. At the end of the review a distillation of all references to labor topics which appear in the text's index is included. This gives an approximate idea of the quantitative coverage of labor in the text; of the tone, emphasis and selections of topics dealt within the text's narrative; and of whether the labor topic is merely cited or listed, or whether it is analyzed and described. An introduction to the survey and review summarizes the labor events and terms regarded as basic to an adequate treatment of organized labor. The summary evaluation placed at, the end of each text's review is based upon the extent to which the text included the items listed in a meaningful way for the student. -

Marie Louise Berneri a Tribute

The Anarchist Library Anti-Copyright Marie Louise Berneri A Tribute Phillip Sansom Phillip Sansom Marie Louise Berneri A Tribute June, 1977 Zero Number 1, June, 1977, page 9 Scanned from original. theanarchistlibrary.org June, 1977 Workers in Stalin’s Russia. M.L. Berneri. Freedom Press, 1944. “Sexuality and Freedom.” M.L. Berneri. Now no. 5. Published by George Woodcock. Journey Through Utopia. M.L. Berneri. Routledge Kegan Paul. 1950. Contents Marie Louise Berneri, A tribute, Freedom Press 1949. Neither East nor West, Selected Writings of Marie Louise Berneri. Edited by Vernon Richards. Freedom Press, 1952 References 13 14 3 References 13 And she finishes in her own words with: “The importance Note: Zero (Anarchist/Anarca-feminist Newsmagazine) was of Dr. Reich’s theories is enormous. To those who do not seek published in London in the late 1970s. intellectual exercise, but means of saving mankind from the “We cannot build until the working class gets rid of its illu- destruction it seems to be approaching, this book will be an sions, its acceptance of bosses and faith in leaders. Our pol- individual source of help and encouragement. To anarchists the icy consists in educating it, in stimulating its class instinct fundamental belief in human nature, in complete freedom from and teaching methods of struggle…It is a hard and long task, the authority of the family, the Church and the State will be but…our way of refusing to attempt the futile task of patching familiar, but the scientific arguments put forward to back this up a rotten world, but of striving to build a new one, is notonly belief will form an indispensible addition to their theoretical constructive but is also the only way out.” knowledge.” Space restricts detailed mention of all those who, as she – Marie Louise Berneri, December, 1940 would have been the first to admit, Influenced her develop- ment. -

Seattle General Strike

Northwest History Consortium Seattle General Strike Omar Crowder th 11 Grade National Standard Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930) / Standards 1 and 3 Standard 1: How Progressives and others addressed problems of industrial capitalism, urbanization, and political corruption Standard 3: How the United States changed from the end of World War I to the eve of the Great Depression Washington State Standards (EALRs) History 4.1.2: Students under how the following themes and developments help to define eras in US history: reform, prosperity, and the Great Depression (1918 - 1939). Social Studies Skills 5.1.2: Students evaluate the depth of a position on an issue or event. BACKGROUND . "The Seattle General Strike of February 1919 was the first city-wide labor action in America to be proclaimed a 'general strike.' It led off a tumultuous era of post-World War I labor conflict that saw massive strikes shut down the nation's steel, coal, and meatpacking industries and threaten civil unrest in a dozen cities. The strike began in shipyards that had expanded rapidly with war production contracts. 35,000 workers expected a post-war pay hike to make up for two years of strict wage controls imposed by the federal government. When regulators refused, the Metal Trades Council union alliance declared a strike and closed the yards. After an appeal to Seattle’s powerful Central Labor Council for help, most of the city’s 110 local unions voted to join a sympathy walkout. The Seattle General Strike lasted less than a week but the memory of that event has continued to be of interest and importance for more than 80 years." Gregory, James N., Professor. -

Women, Wobblies, Respectability, and the Law in the Pacific Northwest, 1905-1924

Beyond the Rebel Girl: Women, Wobblies, Respectability, and the Law in the Pacific Northwest, 1905-1924 by Heather Mayer M.A., University of California, Riverside, 2006 B.A., Portland State University, 2003 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Heather Mayer 2015 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2015 Approval Name: Heather Mayer Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (History) Title of Thesis: Beyond the Rebel Girl: Female Wobblies, Respectability, and the Law in the Pacific Northwest, 1905-1924. Examining Committee: Chair: Roxanne Panchasi Assoc. Professor Mark Leier Senior Supervisor Professor of History Karen Ferguson Supervisor Professor of Urban Studies/History Stephen Collis Internal/External Examiner Supervisor Professor of English Laurie Mercier External Examiner Professor, Department of History Washington State University- Vancouver Date Defended/Approved: February 20, 2015 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii ABSTRACT This thesis is a study of men and women associated with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in the states of Oregon and Washington, from the time of the union’s founding in 1905, to the release of a large group of political prisoners in 1924. IWW membership in this region has long been characterized as single, male, itinerant laborers, usually working in lumber or agriculture, and historians have generally focused on the perspective of this group of men. There were, however, women and men with wives and children who were active members of the organization, especially in the cities of Portland, Spokane, Everett, and Seattle. IWW halls in these cities often functioned as community centers, with family friendly events and entertainment. -

Witness for the Prosecution

Witness for the Prosecution Colin Ward 1974 The revival of interest in anarchism at the time of the Spanish Revolution in 1936 ledtothe publication of Spain and the World, a fortnightly Freedom Press journal which changed to Revolt! in the months between the end of the war in Spain and the beginning of the Second World War. Then War Commentary was started, its name reverting to the traditional Freedom inAugust 1945. As one of the very few journals which were totally opposed to the war aims of both sides, War Commentary was an obvious candidate for the attentions of the Special Branch, but it was not until the last year of the war that serious persecution began. In November 1944 John Olday, the paper’s cartoonist, was arrested and after a protracted trial was sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment for ‘stealing by finding an identity card’. Two months earlier T. W. Brown of Kingston had been jailed for 15 months for distributing ‘seditious’ leaflets. The prosecution at the Old Bailey had drawn the attention of the court to the fact that thepenalty could have been 14 years. On 12 December 1944, officers of the Special Branch raided the Freedom Press office andthe homes of four of the editors and sympathisers. Search warrants had been issued under Defence Regulation 39b, which declared that no person should seduce members of the armed forces from their duty, and Regulation 88a which enabled articles to be seized if they were evidence of the commission of such an offence. At the end of December, Special Branch officers, led byDetec- tive Inspector Whitehead, searched the belongings of soldiers in various parts of the country.