Witness for the Prosecution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rebel Alliances

Rebel Alliances The means and ends 01 contemporary British anarchisms Benjamin Franks AK Pressand Dark Star 2006 Rebel Alliances The means and ends of contemporary British anarchisms Rebel Alliances ISBN: 1904859402 ISBN13: 9781904859406 The means amiemls 01 contemllOranr British anarchisms First published 2006 by: Benjamin Franks AK Press AK Press PO Box 12766 674-A 23rd Street Edinburgh Oakland Scotland CA 94612-1163 EH8 9YE www.akuk.com www.akpress.org [email protected] [email protected] Catalogue records for this book are available from the British Library and from the Library of Congress Design and layout by Euan Sutherland Printed in Great Britain by Bell & Bain Ltd., Glasgow To my parents, Susan and David Franks, with much love. Contents 2. Lenini8t Model of Class 165 3. Gorz and the Non-Class 172 4. The Processed World 175 Acknowledgements 8 5. Extension of Class: The social factory 177 6. Ethnicity, Gender and.sexuality 182 Introduction 10 7. Antagonisms and Solidarity 192 Chapter One: Histories of British Anarchism Chapter Four: Organisation Foreword 25 Introduction 196 1. Problems in Writing Anarchist Histories 26 1. Anti-Organisation 200 2. Origins 29 2. Formal Structures: Leninist organisation 212 3. The Heroic Period: A history of British anarchism up to 1914 30 3. Contemporary Anarchist Structures 219 4. Anarchism During the First World War, 1914 - 1918 45 4. Workplace Organisation 234 5. The Decline of Anarchism and the Rise of the 5. Community Organisation 247 Leninist Model, 1918 1936 46 6. Summation 258 6. Decay of Working Class Organisations: The Spani8h Civil War to the Hungarian Revolution, 1936 - 1956 49 Chapter Five: Anarchist Tactics Spring and Fall of the New Left, 7. -

Marie Louise Berneri a Tribute

The Anarchist Library Anti-Copyright Marie Louise Berneri A Tribute Phillip Sansom Phillip Sansom Marie Louise Berneri A Tribute June, 1977 Zero Number 1, June, 1977, page 9 Scanned from original. theanarchistlibrary.org June, 1977 Workers in Stalin’s Russia. M.L. Berneri. Freedom Press, 1944. “Sexuality and Freedom.” M.L. Berneri. Now no. 5. Published by George Woodcock. Journey Through Utopia. M.L. Berneri. Routledge Kegan Paul. 1950. Contents Marie Louise Berneri, A tribute, Freedom Press 1949. Neither East nor West, Selected Writings of Marie Louise Berneri. Edited by Vernon Richards. Freedom Press, 1952 References 13 14 3 References 13 And she finishes in her own words with: “The importance Note: Zero (Anarchist/Anarca-feminist Newsmagazine) was of Dr. Reich’s theories is enormous. To those who do not seek published in London in the late 1970s. intellectual exercise, but means of saving mankind from the “We cannot build until the working class gets rid of its illu- destruction it seems to be approaching, this book will be an sions, its acceptance of bosses and faith in leaders. Our pol- individual source of help and encouragement. To anarchists the icy consists in educating it, in stimulating its class instinct fundamental belief in human nature, in complete freedom from and teaching methods of struggle…It is a hard and long task, the authority of the family, the Church and the State will be but…our way of refusing to attempt the futile task of patching familiar, but the scientific arguments put forward to back this up a rotten world, but of striving to build a new one, is notonly belief will form an indispensible addition to their theoretical constructive but is also the only way out.” knowledge.” Space restricts detailed mention of all those who, as she – Marie Louise Berneri, December, 1940 would have been the first to admit, Influenced her develop- ment. -

Information Liberation Challenging the Corruptions of Information Power

Information liberation Challenging the corruptions of information power Brian Martin FREEDOM PRESS London 1998 First published 1998 by Freedom Press 84b Whitechapel High Street London E1 7QX ISBN 0 900384 93 X printed in Great Britain by Aldgate Press, Gunthorpe Street, London E1 7RQ Contents 1 Power tends to corrupt 1 2 Beyond mass media 7 3 Against intellectual property 29 4 Antisurveillance 57 5 Free speech versus bureaucracy 83 6 Defamation law and free speech 107 7 The politics of research 123 8 On the value of simple ideas 143 9 Celebrity intellectuals 164 10 Toward information liberation 172 Index 176 (The index is not included in this electronic edition since, due to slight differences in layout, not all page references are correct.) About Freedom Press Freedom Press was founded in 1886 by a group which included Charlotte Wilson and Peter Kropotkin. Its publication Freedom, currently a fortnightly, is the oldest anarchist newspaper in continuous production. Other publications include The Raven, a quarterly of anarchist thought begun in 1987, and some 70 book titles currently in print. Authors range from anarchist classics like Kropotkin, Malatesta, Rudolf Rocker, Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman, to contemporary thinkers like Harold Barclay, Colin Ward and Murray Bookchin. Subjects include anthropology, economics, ecology, education, utopias, capitalism, the state, war and peace, children, land, housing, transport and much more, and the arts are not neglected. There is a set of portrait/biography cards by Clifford Harper, several books of hilarious anarchist strip cartoons, a book of photographs and a children’s story book. Freedom Press is also the wholesale distributor for several other anarchist publishers, and runs a retail bookshop in Angel Alley alongside Whitechapel Art Gallery, open six days a week, selling books on anarchism and related subjects from all sorts of publishers, over the counter and by mail. -

The “ Rising” in Catalonia

I can really be free when those around me, both men and women, are also free. The li berty of others, far from limit ing or negating my own, is, on the contrary, its necessary con dition and guarantee. —B a k u n i n PRICE 2d— U.S.A. 5 CENTS. VOLUME 1, NUMBER 13. JUNE 4th, 1937. OPEN LETTER TO FEDERICA MONTSENY lAfclante, juventod; a luchar como titanes 1 By Camillo Berneri (This letter is taken from the Guerra di Classe of April 14th, 1937 (organ of the Italian Syndicalist Union, affiliated with the A IT ) published at Barcelona. It bears the signature of Camillo Bemert the well known militant anarchist, who, for several months, acted as the political delegate with the Errico Malatesta Battalion— and was addressed to Frederica Atont- seny, member of the Peninsular Committee of the F A I and Minister of Hygiene and Public Assistance in the Valencia Government. The text is reproduced almost in its entirety. The introduction only is missing—and that served solely to eliminate any personal animosity from the discussion by affirming the friendship and esteem of the signatory for his correspondent. — Eds.) REVOLUTIONARY SPAIN AND icith his practical realism, etc.” And I wholeheartedly approved of Voline’s THE POLICY OF reply in “Terre Libre” to your COLLABORATION thoroughly inexact statements on the Russian Anarchist Movement. H AVE not been able to accept But these are not the subjects I calmly the identity— which you I wish to take up with you now. On affirm— as between the Anarchism of these and other things, I hope, some Bakunin and the Federalist Republic day, to talk personally with you. -

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer Raids to the Sixties by Andrew Cornell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Social and Cultural Analysis Program in American Studies New York University January, 2011 _______________________ Andrew Ross © Andrew Cornell All Rights Reserved, 2011 “I am undertaking something which may turn out to be a resume of the English speaking anarchist movement in America and I am appalled at the little I know about it after my twenty years of association with anarchists both here and abroad.” -W.S. Van Valkenburgh, Letter to Agnes Inglis, 1932 “The difficulty in finding perspective is related to the general American lack of a historical consciousness…Many young white activists still act as though they have nothing to learn from their sisters and brothers who struggled before them.” -George Lakey, Strategy for a Living Revolution, 1971 “From the start, anarchism was an open political philosophy, always transforming itself in theory and practice…Yet when people are introduced to anarchism today, that openness, combined with a cultural propensity to forget the past, can make it seem a recent invention—without an elastic tradition, filled with debates, lessons, and experiments to build on.” -Cindy Milstein, Anarchism and Its Aspirations, 2010 “Librarians have an ‘academic’ sense, and can’t bare to throw anything away! Even things they don’t approve of. They acquire a historic sense. At the time a hand-bill may be very ‘bad’! But the following day it becomes ‘historic.’” -Agnes Inglis, Letter to Highlander Folk School, 1944 “To keep on repeating the same attempts without an intelligent appraisal of all the numerous failures in the past is not to uphold the right to experiment, but to insist upon one’s right to escape the hard facts of social struggle into the world of wishful belief. -

Journeying Through Utopia: Anarchism, Geographical Imagination and Performative Futures in Marie-Louise Berneri’S Works

Investigaciones Geográficas • Instituto de Geografía •UNAM eISSN: 2448-7279 • DOI: dx.doi.org/10.14350/rig.60026 • ARTÍCULOS Núm. 100 • Diciembre • 2019 • e60026 www.investigacionesgeograficas.unam.mx Journeying through Utopia: anarchism, geographical imagination and performative futures in Marie-Louise Berneri’s works Un viaje a través de la utopía: anarquismo, imaginación geográfica y futuros performativos en la obra de Marie-Louise Berneri Federico Ferretti* Recibido: 25/07/2019. Aceptado: 12/09/2019. Publicado: 1/12/2019. Abstract. This paper addresses works and archives of Resumen. Este articulo aborda los trabajos y archivos de transnational anarchist intellectual Marie-Louise Berneri la militante anarquista transnacional Maria Luisa Berneri (1918-1949), author of a neglected but very insightful (1918-1949), autora de un estudio poco conocido pero muy history of utopias and of their spaces. Extending current significativo sobre las historias de las utopías y sus espacios. literature on anarchist geographies, utopianism and on the Al ampliar la literatura actual sobre geografías anarquistas, relation between geography and the humanities, I argue utopismo y sobre la relación entre la geografía y las ‘humani- that a distinction between authoritarian and libertarian dades’, defiendo que una distinción entre utopías libertarias utopias is key to understanding the political relevance of y utopías autoritarias es esencial para comprender la impor- the notion of utopia, which is also a matter of space and tancia política del concepto de utopía, que es también un geographical imagination. Berneri’s criticisms to utopia were asunto de espacio y de imaginación geográfica. Las críticas eventually informed by notions of anti-colonialism and anti- de Berneri a la utopía se inspiraron en su anticolonialismo y authoritarianism, especially referred to her original critique su antiautoritarismo, centrado especialmente en su original of twentieth-century totalitarian regimes. -

Anarchy in Action Burned.” Immediately After the Franco Insurrec- Tion, the Land Was Expropriated and Village Life Collectivised

“In its miserable huts live the poor inhabitants of a poor province; eight thousand people, but the streets are not paved, the town has no newspaper, no cinema, neither a cafe nor a library. On the other hand, it has many churches that have been Anarchy in Action burned.” Immediately after the Franco insurrec- tion, the land was expropriated and village life collectivised. “Food, clothing, and tools were Colin Ward distributed equitably to the whole population. Money was abolished, work collectivised, all goods passed to the community, consumption was socialised. It was, however, not a socialisation of wealth but of poverty.” Work continued as before. An elected council appointed committees to organise the life of the commune and its relations to the outside world. The necessities of life were distributed freely, insofar as they were available. A large number of refugees were accommodated. A small library was established, and a small school of design. The document closes with these words: “The whole population lived as in a large family; functionaries, delegates, the secretary of the syndicates, the members of the municipal council, all elected, acted as heads of a family. But they were controlled, because special privilege or corruption would not be tolerated. Membrilla, is perhaps the poorest village of Spain, but it is the most just”.23 And Chomsky comments: “An account such as this, with its concern for human relations and the ideal of a just society, 23 ibid. The best available accounts in English of the collectivisation of industry and agriculture in the Spanish revolution are in Vernon Richards, Lessons of the Spanish Revolution (London, Freedom Press, 2nd ed. -

Vernon Richards (1975), Paris, 10/18

ENSEIGNEMENT DE LA RÉVOLUTION ESPAGNOLE Vernon Richards (1975), Paris, 10/18 http://www.somnisllibertaris.com/libro/enseignementdelarevolution/index03.htm PRÉFACE p. 2 POST-SCRIPTUM p. 4 DEUXIEME PARTIE (Introduction) PREMIERE PARTIE (Introduction) CHAPITRE XVI CHAPITRE I CHAPITRE XVII CHAPITRE II CHAPITRE XVIII CHAPITRE III CHAPITRE XIX CHAPITRE IV CHAPITRE XX CHAPITRE V CHAPITRE VI CONCLUSION CHAPITRE VII CHAPITRE VIII BIBLIOGRAPHIE CHAPITRE IX NOTES CHAPITRE X CHAPITRE XI CHAPITRE XII CHAPITRE XIII CHAPITRE XIV CHAPITRE XV 1 PRÉFACE La Révolution est trop souvent assimilée à la Russie, à une certaine image du marxisme qui oublie la création de la Tchéka (commission extraordinaire de lutte contre le sabotage et la contre-révolution) par Lénine, la répression du soulèvement populaire de Kronstadt, de l’Opposition Ouvrière — pourtant opposée aux Kronstadtiens — et du mouvement anarchiste d’Ukraine par le même Lénine, avec l’accord de Trotsky et de Staline. Plus récemment, l’invasion de la Tchécoslovaquie, les mesures contre les quelques intellectuels russes dignes de ce nom, les accords économiques avec l’Ouest (gazoducs avec les USA et l’Europe occidentale), sans oublier la coexistence nord-américano-chinoise-chinoise et les relations diplomatiques entre Pékin et Ankara et Madrid, démontrent que le marxisme-léninisme n’est que l’idéologie d’une nouvelle classe dirigeante identique à la nôtre. La Révolution pour l’émancipation des travailleurs, une pratique non tarée, il faut les chercher plus près de nous, dans l’Espagne de 1936-1939, dont les aspects sociaux commencent a être connus grâce à Chomsky, Guérin, Leval, Lorenzo et nous-mêmes. Des millions de travailleurs faisant tourner les usines et s’occupant des cultures et transformant l’économie de consommation capitaliste en économie de guerre, en dépit du sabotage des républicains. -

Anarchist Responses to a Pandemic the COVID-19 Crisis As a Case Study in Mutual Aid

The Anarchist Library (Mirror) Anti-Copyright Anarchist Responses to a Pandemic The COVID-19 Crisis as a Case Study in Mutual Aid Nathan Jun & Mark Lance Nathan Jun & Mark Lance Anarchist Responses to a Pandemic The COVID-19 Crisis as a Case Study in Mutual Aid June 17, 2020 Retrieved on 2020-06-24 from kiej.georgetown.edu This is an advance copy of an article that will appear inprint in September 2020 as part of the KIEJ’s special double issue on Ethics, Pandemics, and COVID-19. usa.anarchistlibraries.net June 17, 2020 SYC. n.d.. “Serve Your City.” www.serveyourcitydc.org/ Timm, Jane. 2020. “Fact-checking President Donald Trump’s Claims about Coronavirus.” NBC News. April 2. www.nbcnews.com. 27 ——— 1974. Fields, Factories and Workshops. Oakland: AK Press. Malatesta, Errico. 1974. Anarchy, edited by Vernon Richards. London: Freedom Press. ——— 2015. Life and Ideas, translated by Vernon Richards. Oak- Contents land: PM Press. Mark, Michelle. 2020. Trump is Reportedly Fixated on Keeping the Number of Official US Coronavirus Cases Abstract ......................... 5 as Low as Possible — Despite Indications the Disease §1. The Situation in Washington, DC, March–April has Spread Wider than He Wants.” Business Insider. 2020 ........................ 6 www.businessinsider.com A. National Government Responses . 6 May, Todd. 1994. The Political Philosophy of Poststructuralist B. More Local Responses ............ 7 Anarchism. University Park: The Pennsylvania State Uni- §2. Anarchism ..................... 10 versity Press. A. Mutual Aid . 10 ——— 2009. “Democracy is Where We Make it: The Relevance B. Organization vs. Rule . 15 of Jacques Ranciere.” Symposium 13(1): Spring/Printemps. C. Authority .................. -

THE FALL of MALAGA Government's Criminal Negligence Responsible

Consider the origin of all fortunes, whether arising out of commerce, finance, manu factures, or the land. Every where you will find that the wealth of the wealthy springs from the poverty of the poor. KROPOTKIN. ('Conquest of Bread) VOLUME 1, NUMBER 11. MAY 1st, 1937. PRICE 2d.—U.S.A. 5 CENTS. Iron, San Sebastien, Durango.... to-day Guernica. Franco, Spanish Patriot and Christian, massacres women and children from the air, while British and French politicians discuss further means of betrayal. Workers ! Show your solidarity with the Basque comrades by imposing your will. Demand active intervention in favour of the Spanish workers fighting for liberty against Italian and German regular Army and Air Force. Now . .. before Bilbao and its heroic people are wiped out. MAY 1st, 1937: ITS SIGNIFICANCE THE FALL OF MALAGA It seems appropriate to us that ity. Once they put power into Government’s Criminal Negligence Responsible a whole page of this issue should the hands of their leaders their be dedicated to our brave Com movement is doomed to failure. rades of Catalonia. For it is Regarding the Fall of Malaga, Yet nothing was done. The C.N.T. dant PELAYO was relieved of his they who are defending not only Workers! Return to your reports appeared from various sources of Malaga established a munition fac command, because he was under sus Spanish territory with their homes this May Day resolved which did not altogether correspond tory where 1,000 persons were busy picion to be in sympathy with the armed fists, but they are also de that your efforts on behalf of with the true facts of the case. -

Catalogue 2018

anarchist publishing Est. 1886 Catalogue 2018 INTRO/INDEX wELCOME TO THE FREEDOM CATALOGUE Anarchism is almost certainly the most interesting political movement to have slipped under the radar of public discourse. It is rarely pulled up in today’s media as anything other than a curio or a threat. But over the course of 175 years since Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s declaration “I am an anarchist” this philosophy of direct action and free thought has repeatedly changed the world. From Nestor Makhno’s legendary war on both Whites and Reds in 1920s Ukraine, to the Spanish Civil War, to transformative ideals in the 1960s and street-fought antifascism in the 1980s, anarchism remains a vital part of any rounded understanding of humanity’s journey from past to present, let alone the possibilities for its future. For most of that time there has been Freedom Press. Founded in 1886, brilliant thinkers past and present have published through Freedom, allowing us to present today a kaleidoscope of classic works from across the modern age. Featuring books from Peter Kropotkin, Nicolas Walter, William Blake, Errico Malatesta, Colin Ward and many more, this catalogue offers much of what you might need to understand a fascinating creed. ordering direct trade You can order online, by email, phone Trade orders come from Central Books, or post (details below). Our business who offer 33% stock discounts as hours are 10am-6pm, Monday to standard. Saturday. Postage is free within the UK, with You can pay via Paypal on our £2.50 extra for orders from abroad — website. -

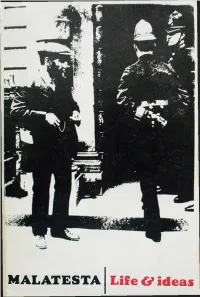

MALATESTA His Life Ideas

M ALATESTA Life & id eas ERRICO MALATESTA His Life Ideas Compiled and Edited by VERNON RICHARDS m m i i ® 2 9 3 4 Ri/E ST-URSAiH, MONTREAL 131 T*L 15145 844-4076 LONDON FREEDOM PRESS 1965 First Published 1965 by FREEDOM PRESS 17a Maxwell Road, London, S.W.6 Printed by Express Printers London, E.l Printed in Gi. Britain To the memory of Camillo and Giovanna Berneri and their daughter Marie-Louise Berneri CONTENTS Editor’s Foreword PaSe 9 P a r t O n e Introduction: Anarchism and Anarchy 19 I 1 Anarchist Schools of Thought 29 2 Anarchist-Communism 34 3 Anarchism and Science 38 4 Anarchism and Freedom 47 5 Anarchism and Violence 53 6 Attentats 61 it 7 Ends and Means 68 8 Majorities and Minorities 72 9 Mutual Aid 93 10 Reformism 98 11 Organisation 83 in 12 Production and Distribution 91 13 The Land 97 14 Money and Banks 100 15 Property 102 16 Crime and Punishment 105 IV 17 Anarchists and the Working Class Movements 113 18 The Occupation of the Factories 134 19 Workers and Intellectuals 137 20 Anarchism, Socialism and Communism 141 21 Anarchists and the Limits of Political Co-Existence 148 v 22 The Anarchist Revolution 153 23 The Insurrection 163 24 Expropriation 167 25 Defence of the Revolution 170 VI 26 Anarchist Propaganda 177 27 An Anarchist Programme 182 P a r t Two Notes for a Biography (V.R.) 201 Source Notes 241 A PPEN D IC ES I Anarchists have forgotten their Principles (E.M.