Firebrand and the Forging of a New Anarchism: Anarchist Communism and Free Love Fall 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Danziger, Edmund Jefferson Indians and Bureaucrats ENG 1974 University of Illinois Press Daris & Al

1 Catalogue des livres de la bibliothèque anarchiste DIRA Mai 2011 [email protected] bibliothequedira.wordpress.com 514-843-2018 2035 Blv Saint-Laurent, Montréal Bibliothèque DIRA, Mai 2011. 2 Présentation ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 -A- ................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 -B- ................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 -C- ............................................................................................................................................................................... 13 -D- ............................................................................................................................................................................... 20 -E- ............................................................................................................................................................................... 23 -F- ................................................................................................................................................................................ 24 -G- .............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Brill's Companion to Anarchism and Philosophy

Brill’s Companion to Anarchism and Philosophy Edited by Nathan Jun LEIDEN | BOSTON For use by the Author only | © 2018 Koninklijke Brill NV Contents Editor’s Preface ix Acknowledgments xix About the Contributors xx Anarchism and Philosophy: A Critical Introduction 1 Nathan Jun 1 Anarchism and Aesthetics 39 Allan Antliff 2 Anarchism and Liberalism 51 Bruce Buchan 3 Anarchism and Markets 81 Kevin Carson 4 Anarchism and Religion 120 Alexandre Christoyannopoulos and Lara Apps 5 Anarchism and Pacifism 152 Andrew Fiala 6 Anarchism and Moral Philosophy 171 Benjamin Franks 7 Anarchism and Nationalism 196 Uri Gordon 8 Anarchism and Sexuality 216 Sandra Jeppesen and Holly Nazar 9 Anarchism and Feminism 253 Ruth Kinna For use by the Author only | © 2018 Koninklijke Brill NV viii CONTENTS 10 Anarchism and Libertarianism 285 Roderick T. Long 11 Anarchism, Poststructuralism, and Contemporary European Philosophy 318 Todd May 12 Anarchism and Analytic Philosophy 341 Paul McLaughlin 13 Anarchism and Environmental Philosophy 369 Brian Morris 14 Anarchism and Psychoanalysis 401 Saul Newman 15 Anarchism and Nineteenth-Century European Philosophy 434 Pablo Abufom Silva and Alex Prichard 16 Anarchism and Nineteenth-Century American Political Thought 454 Crispin Sartwell 17 Anarchism and Phenomenology 484 Joeri Schrijvers 18 Anarchism and Marxism 505 Lucien van der Walt 19 Anarchism and Existentialism 559 Shane Wahl Index of Proper Names 583 For use by the Author only | © 2018 Koninklijke Brill NV CHAPTER 10 Anarchism and Libertarianism Roderick T. Long Introduction -

Anarchy! an Anthology of Emma Goldman's Mother Earth

U.S. $22.95 Political Science anarchy ! Anarchy! An Anthology of Emma Goldman’s MOTHER EARTH (1906–1918) is the first An A n t hol o g y collection of work drawn from the pages of the foremost anarchist journal published in America—provocative writings by Goldman, Margaret Sanger, Peter Kropotkin, Alexander Berkman, and dozens of other radical thinkers of the early twentieth cen- tury. For this expanded edition, editor Peter Glassgold contributes a new preface that offers historical grounding to many of today’s political movements, from liber- tarianism on the right to Occupy! actions on the left, as well as adding a substantial section, “The Trial and Conviction of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman,” which includes a transcription of their eloquent and moving self-defense prior to their imprisonment and deportation on trumped-up charges of wartime espionage. of E m m A g ol dm A n’s Mot h er ea rt h “An indispensable book . a judicious, lively, and enlightening work.” —Paul Avrich, author of Anarchist Voices “Peter Glassgold has done a great service to the activist spirit by returning to print Mother Earth’s often stirring, always illuminating essays.” —Alix Kates Shulman, author of Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen “It is wonderful to have this collection of pieces from the days when anarchism was an ism— and so heady a brew that the government had to resort to illegal repression to squelch it. What’s more, it is still a heady brew.” —Kirkpatrick Sale, author of The Dwellers in the Land “Glassgold opens with an excellent brief history of the publication. -

Haymarket Riot (Chicago: Alexander J

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 HAYMARKET MARTYRS1 MONUMENT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service______________________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Haymarket Martyrs' Monument Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 863 South Des Plaines Avenue Not for publication: City/Town: Forest Park Vicinity: State: IL County: Cook Code: 031 Zip Code: 60130 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): Public-Local: _ District: Public-State: _ Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing ___ buildings ___ sites ___ structures 1 ___ objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register:_Q_ Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: Designated a NATIONAL HISTrjPT LANDMARK on by the Secreury 01 j^ tai-M NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 HAYMARKET MARTYRS' MONUMENT Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National_P_ark Service___________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Herald of the Future? Emma Goldman, Friedrich Nietzsche and the Anarchist As Superman

The University of Manchester Research Herald of the future? Emma Goldman, Friedrich Nietzsche and the anarchist as superman Document Version Accepted author manuscript Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Morgan, K. (2009). Herald of the future? Emma Goldman, Friedrich Nietzsche and the anarchist as superman. Anarchist Studies, 17(2), 55-80. Published in: Anarchist Studies Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:04. Oct. 2021 Herald of the future? Emma Goldman, Friedrich Nietzsche and the anarchist as superman Kevin Morgan In its heyday around the turn of the twentieth century, Emma Goldman more than anybody personified anarchism for the American public. Journalists described her as anarchy’s ‘red queen’ or ‘high priestess’. At least one anarchist critic was heard to mutter of a ‘cult of personality’.1 Twice, in 1892 and 1901, Goldman was linked in the public mind with the attentats or attempted assassinations that were the movement’s greatest advertisement. -

Sasha and Emma the ANARCHIST ODYSSEY OF

Sasha and Emma THE ANARCHIST ODYSSEY OF ALEXANDER BERKMAN AND EMMA GOLDMAN PAUL AVRICH KAREN AVRICH SASHA AND EMMA SASHA and EMMA The Anarchist Odyssey of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman Paul Avrich and Karen Avrich Th e Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts • London, En gland 2012 Copyright © 2012 by Karen Avrich. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Avrich, Paul. Sasha and Emma : the anarchist odyssey of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman / Paul Avrich and Karen Avrich. p . c m . Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 674- 06598- 7 (hbk. : alk. paper) 1. Berkman, Alexander, 1870– 1936. 2. Goldman, Emma, 1869– 1940. 3. Anarchists— United States— Biography. 4 . A n a r c h i s m — U n i t e d S t a t e s — H i s t o r y . I . A v r i c h , K a r e n . II. Title. HX843.5.A97 2012 335'.83092273—dc23 [B] 2012008659 For those who told their stories to my father For Mark Halperin, who listened to mine Contents preface ix Prologue 1 i impelling forces 1 Mother Rus sia 7 2 Pioneers of Liberty 20 3 Th e Trio 30 4 Autonomists 43 5 Homestead 51 6 Attentat 61 7 Judgment 80 8 Buried Alive 98 9 Blackwell’s and Brady 111 10 Th e Tunnel 124 11 Red Emma 135 12 Th e Assassination of McKinley 152 13 E. G. Smith 167 ii palaces of the rich 14 Resurrection 181 15 Th e Wine of Sunshine and Liberty 195 16 Th e Inside Story of Some Explosions 214 17 Trouble in Paradise 237 18 Th e Blast 252 19 Th e Great War 267 20 Big Fish 275 iii -

Jay Fox: the Life and Times of an American Radical

Eastern Washington University EWU Digital Commons EWU Masters Thesis Collection Student Research and Creative Works 2016 Jay Fox: the life and times of an American radical David J. Collins Eastern Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.ewu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Collins, David J., "Jay Fox: the life and times of an American radical" (2016). EWU Masters Thesis Collection. 338. https://dc.ewu.edu/theses/338 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research and Creative Works at EWU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in EWU Masters Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of EWU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JAY FOX: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF AN AMERICAN RADICAL A Thesis Presented To Eastern Washington University Cheney, Washington In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History By David J. Collins Spring 2016 ii iii iv Acknowledgements First, I have to acknowledge Ross K. Rieder who generously made his collection of Jay Fox papers available to me, as well as permission to use it for this project. Next, a huge thanks to Dr. Joseph U. Lenti who provided guidance and suggestions for improving the project, and put in countless hours editing and advising me on revisions. Dr. Robert Dean provided a solid knowledge of the time period through coursework and helped push this thesis forward. Dr. Mimi Marinucci not only volunteered her time to participate on the committee, but also provided support and guidance to me from my first year as an undergraduate at Eastern Washington University, and continues to be an influential mentor today. -

Ezra Heywood, William Batchelder Greene, Stephen Pearl Andrews, and Benjamin Tucker– Who Were from Thoreau’S Home State of Massachusetts and Were His Contemporaries

19TH-CENTURY MASSACHUSETTS ANARCHISTS: EZRA HERVEY HEYWOOD One of the staunchest of Thoreau attackers, Vincent Buranelli, in “The Case Against Thoreau” (Ethics 67), would allege in 1957 that Henry from time to time altered his principles and his tactics with little or no legitimation. Buranelli charged him with having practiced a radical and dangerous politics. In his article we learn that Thoreau’s political theory “points forward to Lenin, the ‘genius theoretician’ whose right it is to force a suitable class consciousness on those who do not have it, and to the horrors that resulted from Hitler’s ‘intuition’ of what was best for Germany.” In his article we learn that Thoreau’s defense of John Brown gave “allegiance to inspiration rather than to ratiocination and factual evidence.” According to this source “Thoreau’s commitment to personal revelation made him an anarchist.” 1 An anarchist? According to the ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA, the term “anarchism” derives from a Greek root signifying “without a rule” and indicates “a cluster of doctrines whose principal uniting feature is the belief that government is both harmful and unnecessary.” So who the hell are these people, the “Anarchists”? —Well, although an early theorist of the no- 1. The initials of the person who prepared this material for the EB were “G.W.” — the PROPÆDIA volume lists these initials as belonging to George Woodcock, apparently a recidivist encyclopedist as he is listed as also having prepared a number of other ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA articles. HDT WHAT? INDEX EZRA HERVEY -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5030

VOL. I—NO. 6 , APRIL, 1925 PRICE 5 CENTS The Evolution of Anarchist Theories E shall attempt to review in lence: rent, interest, profit, and taxes. The further develbpmeht of Anar this brief sketch the theoreti They demand freedom of production for chist theories therefore centered around W cal developmlent of Anar the individual and for the voluntary the problem qf harmonizing, economic chism by describing the ideas whence groups in unrestrained competition in conditions with the basic principle of Anarchist thought originated and the the open market. The principle of the a free society. The idea of equitable manner in which the various. modern "full product of one's labor" is main and direct exchange repeatedly sought schools of Anarchism gradually devel tained by securing to each, as his in practical expression, as in the London oped. We shall therefore leave out of alienable private possesMon, all that he Industrial Fairs, also in America aud consideration all general historical dis is able to gain by competing against France. Similar ideas are still cham cussions, biographic and literary data, the whole field. Thel restrictions en pioned by the American, English, and and the external history of the move forced in present society by monopoly Australian Individualist Anarchists, as ment. —aided by its^ tool, the State—^being well as by somie followers of Proudhon and Stirner. Our modern attitude, how There never lacked men to advocate eliminated, the equal opportunity of all ever, is opposed to these ideas on the subtle projects of governmental organ niust result in the equitable exchange ground that the requirements of com ization and regulation of production of equal values. -

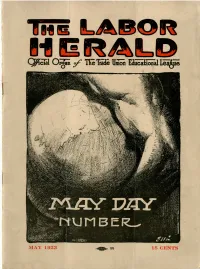

Issue No. 3, May, 1923

QP?cial Organ ?f TKe Trade Union Educational Lesli MAY 1923 99 15 GENTS JUST OFF THE PRESS The Labor Defense Council Pamphlet A masterful presentation of the background of the Michigan Criminal Syndi- calism Case, the high points of the prosecution and the defense and a clear cut statement of the issues involved. • / No one who wishes to keep informed about the development of the governmental attacks on labor can afford to miss this brilliant pamphlet;. For those who want to aid in the defense of the men and -vjromen now being pro- secuted, it is an absolute necessity. 24 pages, 6x9 inch, A permanent con- Cover design by tribution to Ameri- can Labor Litera- Fred Ellis, illustra- ture. A smashing ted with 22 pictures attack on the Labor- of the principals of baiters and their the defense and the masters, the "Cap- prosecution and of tains" of Industry- A spirited defense scenes taken at the of' the rights of Foster trial. labor. Published By LABOR DEFENSE COUNCIL 166 W. Washington St. CHICAGO, ILL. ' ' | Price 10 cents ; BUY IT! READ IT! SELL IT! Help the Michigan Defense by Putting a Copy of This Pamphlet in the Hands of Every Worker, Every Lover of Liberty. Order a Bundle to Sell at Union and Mass Meetings ~~j 10 cents a copy, '3 for 25 cents, 14 for a Enclosed please find $ ~ dollar, $6.50 per hundred. Postpaid any for _.:. copies of the place in the U. S. or Canada. Labor Defense Council pamphlet. Address all comimunications and make checks payable to, Name - LABOR DEFENSE COUNCIL I Address .~ Room 307, 166 W. -

Anarchism in Hungary: Theory, History, Legacies

CHSP HUNGARIAN STUDIES SERIES NO. 7 EDITORS Peter Pastor Ivan Sanders A Joint Publication with the Institute of Habsburg History, Budapest Anarchism in Hungary: Theory, History, Legacies András Bozóki and Miklós Sükösd Translated from the Hungarian by Alan Renwick Social Science Monographs, Boulder, Colorado Center for Hungarian Studies and Publications, Inc. Wayne, New Jersey Distributed by Columbia University Press, New York 2005 EAST EUROPEAN MONOGRAPHS NO. DCLXX Originally published as Az anarchizmus elmélete és magyarországi története © 1994 by András Bozóki and Miklós Sükösd © 2005 by András Bozóki and Miklós Sükösd © 2005 by the Center for Hungarian Studies and Publications, Inc. 47 Cecilia Drive, Wayne, New Jersey 07470–4649 E-mail: [email protected] This book is a joint publication with the Institute of Habsburg History, Budapest www.Habsburg.org.hu Library of Congress Control Number 2005930299 ISBN 9780880335683 Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 PART ONE: ANARCHIST SOCIAL PHILOSOPHY 7 1. Types of Anarchism: an Analytical Framework 7 1.1. Individualism versus Collectivism 9 1.2. Moral versus Political Ways to Social Revolution 11 1.3. Religion versus Antireligion 12 1.4. Violence versus Nonviolence 13 1.5. Rationalism versus Romanticism 16 2. The Essential Features of Anarchism 19 2.1. Power: Social versus Political Order 19 2.2. From Anthropological Optimism to Revolution 21 2.3. Anarchy 22 2.4. Anarchist Mentality 24 3. Critiques of Anarchism 27 3.1. How Could Institutions of Just Rule Exist? 27 3.2. The Problem of Coercion 28 3.3. An Anarchist Economy? 30 3.4. How to Deal with Antisocial Behavior? 34 3.5. -

Labor History

319 INSTITUTE OF LABOR AND INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS,, Illinois' Forgotten Labor History By WILLIAM J. ADELMAN I.N.At'T-rl 'TP COF INDUSTRIAL II APR 12 1985 L -. _ UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN / '/ The Institute of Labor and Industrial Relations . was set up at the University of Illinois in 1946 to "foster, establish, and correlate resident instruction, research, and extension work in labor relations." Graduate study . for resident students at the University leads to the degree of Master of Arts and Ph.D. in Labor and Industrial Relations. A new joint degree program leads to the J.D. degree in Law and the A.M. degree in Labor and Industrial Relations. Institute graduates are now working in business, union, and consulting organizations, government agencies and teaching in colleges and universities. Research . is based on the Institute's instruction from the University Board of Trustees to "inquire faithfully, honestly, and impartially into labor-man- agement problems of all types and secure the facts which will lay the foundations of future progress." Current Institute research projects are in the areas of labor-management relations, labor and government, the union as an institution, the public interest in labor and industrial relations, human resources, organizational behavior, comparative and international industrial relations. Extension ... activities are designed to meet the educational needs of adult groups in labor and industrial relations. Classes, conferences and lectures are offered. A wide range of subjects is available - each adapted to the specific needs of labor, management, or public groups. Information . service of the Institute library furnishes data and reference material to any individual or group in reply to factual inquiries on any aspect of labor and industrial relations.