Jay Fox: Anarchist of Home Columbia Magazine, Spring 1990: Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EMMA GOLDMAN, ANARCHISM, and the “AMERICAN DREAM” by Christina Samons

AN AMERICA THAT COULD BE: EMMA GOLDMAN, ANARCHISM, AND THE “AMERICAN DREAM” By Christina Samons The so-called “Gilded Age,” 1865-1901, was a period in American his tory characterized by great progress, but also of great turmoil. The evolving social, political, and economic climate challenged the way of life that had existed in pre-Civil War America as European immigration rose alongside the appearance of the United States’ first big businesses and factories.1 One figure emerges from this era in American history as a forerunner of progressive thought: Emma Goldman. Responding, in part, to the transformations that occurred during the Gilded Age, Goldman gained notoriety as an outspoken advocate of anarchism in speeches throughout the United States and through published essays and pamphlets in anarchist newspapers. Years later, she would synthe size her ideas in collections of essays such as Anarchism and Other Essays, first published in 1917. The purpose of this paper is to contextualize Emma Goldman’s anarchist theory by placing it firmly within the economic, social, and 1 Alan M. Kraut, The Huddled Masses: The Immigrant in American Society, 1880 1921 (Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, 2001), 14. 82 Christina Samons political reality of turn-of-the-twentieth-century America while dem onstrating that her theory is based in a critique of the concept of the “American Dream.” To Goldman, American society had drifted away from the ideal of the “American Dream” due to the institutionalization of exploitation within all aspects of social and political life—namely, economics, religion, and law. The first section of this paper will give a brief account of Emma Goldman’s position within American history at the turn of the twentieth century. -

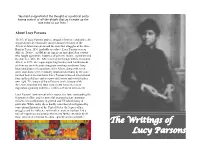

The Writings of Lucy Parsons

“My mind is appalled at the thought of a political party having control of all the details that go to make up the sum total of our lives.” About Lucy Parsons The life of Lucy Parsons and the struggles for peace and justice she engaged provide remarkable insight about the history of the American labor movement and the anarchist struggles of the time. Born in Texas, 1853, probably as a slave, Lucy Parsons was an African-, Native- and Mexican-American anarchist labor activist who fought against the injustices of poverty, racism, capitalism and the state her entire life. After moving to Chicago with her husband, Albert, in 1873, she began organizing workers and led thousands of them out on strike protesting poor working conditions, long hours and abuses of capitalism. After Albert, along with seven other anarchists, were eventually imprisoned or hung by the state for their beliefs in anarchism, Lucy Parsons achieved international fame in their defense and as a powerful orator and activist in her own right. The impact of Lucy Parsons on the history of the American anarchist and labor movements has served as an inspiration spanning now three centuries of social movements. Lucy Parsons' commitment to her causes, her fame surrounding the Haymarket affair, and her powerful orations had an enormous influence in world history in general and US labor history in particular. While today she is hardly remembered and ignored by conventional histories of the United States, the legacy of her struggles and her influence within these movements have left a trail of inspiration and passion that merits further attention by all those interested in human freedom, equality and social justice. -

ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z

1111 ~~ I~ I~ II ~~ I~ II ~IIIII ~ Ii II ~III 3 2103 00341 4723 ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER A Communist's Fifty Yea1·S of ,tV orking-Class Leadership and Struggle - By Elizabeth Gurley Flynn NE'V CENTURY PUBLISIIERS ABOUT THE AUTHOR Elizabeth Gurley Flynn is a member of the National Com mitt~ of the Communist Party; U.S.A., and a veteran leader' of the American labor movement. She participated actively in the powerful struggles for the industrial unionization of the basic industries in the U.S.A. and is known to hundreds of thousands of trade unionists as one of the most tireless and dauntless fighters in the working-class movement. She is the author of numerous pamphlets including The Twelve and You and Woman's Place in the Fight for a Better World; her column, "The Life of the Party," appears each day in the Daily Worker. PubUo-hed by NEW CENTURY PUBLISH ERS, New York 3, N. Y. March, 1949 . ~ 2M. PRINTED IN U .S .A . Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER TAUNTON, ENGLAND, ·is famous for Bloody Judge Jeffrey, who hanged 134 people and banished 400 in 1685. Some home sick exiles landed on the barren coast of New England, where a namesake city was born. Taunton, Mass., has a nobler history. In 1776 it was the first place in the country where a revolutionary flag was Bown, "The red flag of Taunton that flies o'er the green," as recorded by a local poet. A century later, in 1881, in this city a child was born to a poor Irish immigrant family named Foster, who were exiles from their impoverished and enslaved homeland to New England. -

American Periodicals: Politics (Opportunities for Research in the Watkinson Library)

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Watkinson Library (Rare books & Special Watkinson Publications Collections) 2016 American Periodicals: Politics (Opportunities for Research in the Watkinson Library) Leonard Banco Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/exhibitions Part of the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Banco, Leonard, "American Periodicals: Politics (Opportunities for Research in the Watkinson Library)" (2016). Watkinson Publications. 23. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/exhibitions/23 Series Introduction A traditional focus ofcollecting in the Watkinson since we opened on August 28, 1866, has been American periodicals, and we have quite a good representation of them from the late 18th to the early 20th centuries. However, in terms of "discoverability" (to use the current term), it is not enough to represent each of the 600-plus titles in the online catalog. We hope that our students, faculty, and other researchers will appreciate this series of annotated guides to our periodicals, broken down into basic themes (politics, music, science and medicine, children, education, women, etc.), all of which have been compiled by Watkinson Trustee and volunteer Dr. Leonard Banco. We extend our deep thanks to Len for the hundreds of hours he has devoted to this project since the spring of 2014. His breadth of knowledge about the period and his inquisitive nature have made it possible for us to promote a unique resource through this work, which has POLITICS already been of great use to visiting scholars and Trinity classes. Students and faculty keen for projects will take note Introduction of the possibilities! The Watkinson holds 2819th-century American magazines with primarily political content, 11 of which are complete Richard J. -

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: the 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike By Leigh Campbell-Hale B.A., University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1977 M.A., University of Colorado, Boulder, 2005 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado and Committee Members: Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas G. Andrews Mark Pittenger Lee Chambers Ahmed White In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History 2013 This thesis entitled: Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike written by Leigh Campbell-Hale has been approved for the Department of History Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas Andrews Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii Campbell-Hale, Leigh (Ph.D, History) Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike Dissertation directed by Associate Professor Phoebe S.K. Young This dissertation examines the causes, context, and legacies of the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike in relationship to the history of labor organizing and coalmining in both Colorado and the United States. While historians have written prolifically about the Ludlow Massacre, which took place during the 1913- 1914 Colorado coal strike led by the United Mine Workers of America, there has been a curious lack of attention to the Columbine Massacre that occurred not far away within the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike, led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). -

Haymarket Riot (Chicago: Alexander J

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 HAYMARKET MARTYRS1 MONUMENT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service______________________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Haymarket Martyrs' Monument Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 863 South Des Plaines Avenue Not for publication: City/Town: Forest Park Vicinity: State: IL County: Cook Code: 031 Zip Code: 60130 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): Public-Local: _ District: Public-State: _ Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing ___ buildings ___ sites ___ structures 1 ___ objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register:_Q_ Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: Designated a NATIONAL HISTrjPT LANDMARK on by the Secreury 01 j^ tai-M NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 HAYMARKET MARTYRS' MONUMENT Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National_P_ark Service___________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Étienne Cabet

Étienne Cabet (1788-1856) was a French radical whose utopian visions led him to write a book “Voyage to Icarie” and then founded a community called Icaria in the United States. There is no evidence that Cabet actually visited Ikaria though some of the practices he describes in his book were in use in Ikaria, Greece at the time. In Barcelona there is both an “Icaria Square” and an “Icaria Road” both named in honour of Étienne Cabet’s Utopian “Icaria” Étienne Cabet was born in 1788, a year before the fall of the Bastille. For the first forty years of his life he was the typical radical Jacobin of the post-revolutionary generation, untouched by the disillusionment of older men whose youth and young manhood was lived under the Terror, the Directory, and the Napoleonic Empire. In 1820 he gave up a law practice in Dijon and became a director of the French conspiratorial revolutionary organization, the Carbonari. In the Revolution of 1830 he was a member of the Insurrection Committee. Louis Philippe appointed him Attorney General of Corsica, but he was dismissed for his attacks on the government in his book Histoire de la révolution de 1830, and in his journal Le Populaire . He returned to Dijon and was elected Deputy, whereupon he was arraigned on a charge of lèse-majesté and was condemned to two years’ imprisonment and five years’ exile. He went to Brussels, was expelled, and emigrated to England, where he became a disciple of Robert Owen. In the amnesty of 1839, Cabet returned to France and in the next year published a history of the French Revolution, and Voyage en Icarie, a semi-fictional account of a communist society, which he considered a modern version of Thomas More’s Utopia, as improved by the economic theories of Robert Owen. -

From Transcendentalism to Progressivism: the Making of an American Reformer, Abby Morton Diaz (1821-1904)

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2006 From Transcendentalism to Progressivism: The Making of an American Reformer, Abby Morton Diaz (1821-1904). Ann B. Cro East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Cro, Ann B., "From Transcendentalism to Progressivism: The akM ing of an American Reformer, Abby Morton Diaz (1821-1904)." (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2187. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2187 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Transcendentalism to Progressivism: The Making of an American Reformer, Abby Morton Diaz (1821-1904) ____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Cross-Disciplinary Studies East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Liberal Studies ___________________ by Ann B. Cro May 2006 ____________________ Dr. Theresa Lloyd, Chair Dr. Marie Tedesco Dr. Kevin O’Donnell Keywords: Abby Morton Diaz, Transcendentalism, Abolition, Brook Farm, Nationalist Movement ABSTRACT From Transcendentalism to Progressivism: The Making of an American Reformer, Abby Morton Diaz (1821-1904) by Ann B. Cro Author and activist Abby Morton Diaz (1821-1904) was a member of the Brook Farm Transcendental community from 1842 until it folded in 1847. -

Firebrand and the Forging of a New Anarchism: Anarchist Communism and Free Love Fall 2004

The Firebrand and the Forging ofa New Anarchism: Anarchist Communism and Free Love Jessica Moran Fall 2004 Contents Firebrand and its Editors ........................... 8 What is Anarchist Communism? ...................... 12 Anarchism and Sex ............................. 15 Conclusion .................................. 19 2 In January 1895 a small paper appeared in Portland, Oregon. Titled Firebrand, and staunchly and openly advocating anarchist communism and free love, the pa- per was instrumental in the development of American anarchism. The paper sys- tematically brought working-class anarchism and social revolution to an English speaking audience for the first time, influencing the direction of anarchism inthe United States for the next twenty years. Understanding the pivotal position of Fire- brand in what is often considered a dormant period in American anarchist history, is necessary to comprehending the evolution of anarchism in the United States. The American anarchist movement thrived in the last part of the 1890s. Firebrand fos- tered the growth of an anarchist movement that incorporated the economic change fought for by the Haymarket anarchists, along with social issues like free love and individual freedom long advocated by individualist anarchists. Published between 1895 and 1897, Firebrand helped reinvigorate the anarchist movement, and intro- duced an important development that remained part of the anarchist movement throughout the twentieth century. By combining the economic and political argu- ments of anarchist communism with the social and cultural ideas of free love, Fire- brand and its contributors consciously developed an anarchism that appealed to both immigrant and native-born Americans. The anarchism discussed and worked out in the pages of Firebrand influenced and perhaps even formed the American an- archism appearing after the turn of the century, which gained popular expression throughout the Progressive Era. -

S611s6 1901.Pdf

PRICE 5 CENTS. SOCIALISM vs ANARCHY BY A. M. SIMONS Editor of the International Socialist Review. POCKET LIBRARY OF SOCIALISM Monthly,5oc a Year. No. fr,September 15, IQOP -- Published by CHARLES H. KERR & COMPANY (CO-OPERATIVE) 56 Fifth Avenue, Chicago, 111. PREFATORY NOTE. On Sept. 5, 1901, William McKinley, Presi- dent of the United States, was shot by Leon Czolgosz, a self-declared anarchist. On Sept. 13 the President died of his wound. On Sept. 15, while the people were naturally in a state ~ of wild excitement orer the tragedy, ‘A. M. Simons, editor of the International Socialist Rericw, delivered the following address at the Socialist Temple, 120 South Western are- nue, Chicago. The hall was packed to the limit and hundreds were turned away. In response to the general desire of those present, the address is now published, in the hope that it may have some effect in remov ing the prejudice existing against socialism by those who ignorantly confound it with anarchy, Socialism vs. Anfrcby. a Once again the anarchists have proven them. selves the dearest foes of capitalism. The story, long grown old in Europe, haa been repeatti , here. The act of one fanatical criminal at Buf- falo has rallied every force of reaction and ex- ploitation as no avowed defender of capitalism could hope to do. It has long heen recognized in Europe that in every great emergency, when the forces of oppression ,are hardest pressed, they can always hope that some such de& $s this will come to their rescue. Indeed, Bis- marck, who must always hold the palm as the ablest defender of capitalism and the most cun- ning opponent of socialism that the nineteenth century has produced, did not hesitate, when necessary, to commit deeds of violence through the police in order to arouse public opinion. -

Jay Fox: the Life and Times of an American Radical

Eastern Washington University EWU Digital Commons EWU Masters Thesis Collection Student Research and Creative Works 2016 Jay Fox: the life and times of an American radical David J. Collins Eastern Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.ewu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Collins, David J., "Jay Fox: the life and times of an American radical" (2016). EWU Masters Thesis Collection. 338. https://dc.ewu.edu/theses/338 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research and Creative Works at EWU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in EWU Masters Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of EWU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JAY FOX: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF AN AMERICAN RADICAL A Thesis Presented To Eastern Washington University Cheney, Washington In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History By David J. Collins Spring 2016 ii iii iv Acknowledgements First, I have to acknowledge Ross K. Rieder who generously made his collection of Jay Fox papers available to me, as well as permission to use it for this project. Next, a huge thanks to Dr. Joseph U. Lenti who provided guidance and suggestions for improving the project, and put in countless hours editing and advising me on revisions. Dr. Robert Dean provided a solid knowledge of the time period through coursework and helped push this thesis forward. Dr. Mimi Marinucci not only volunteered her time to participate on the committee, but also provided support and guidance to me from my first year as an undergraduate at Eastern Washington University, and continues to be an influential mentor today. -

History 1014 (12) Further Reading

HISTORY 1014 (12): FURTHER READINGS UTOPIAN VISIONS: REVISING COMMUNITY, FAMILY, GENDER ROLES Rosabeth Kanter, Commitment and Community: Communes and Utopias in Sociological Perspective (1972) John V. Chamberlain, “The Spiritual Impetus to Community,” in Gairdner B. Moment and Otto F. Kraushaar, Utopias: the American Experience (1980), 126-139 Carol Weisbrod, “Communal Groups and the Larger Society: Legal Dilemmas,” Communal Societies 12 (1992), 1-19 Lucy Jayne Kamau, “The Anthropology of Space in Harmonist and Owenite New Harmony,” Communal Societies 12 (1992), 68-89 Deirdre Hughes, “The World of Poor Eve: Re-defining Women’s Roles in Nineteenth Century Utopian Communities,” Communal Societies 21 (2001), 95-103 Beverly Gordon, “Dress in American Communal Societies,” Communal Societies 5 (1985), 122- 136 Gayle V. Fischer, “Dressing to Please God: Pants-Wearing Women in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Religious Communities,” Communal Societies 15 (1995), 55-74 CHRONOLOGY OF UTOPIAN AND INTENTIONAL COMMUNITIES Otohiko Okugawa, “Intercommunal Relationships among Nineteenth-century Communal Societies in America,” Communal Societies 3 (1983), 68-82 James Latimore, “Natural Limits on the Size and Duration of Utopian Communities” Communal Societies 11 (1991), 34-61 James A. Kitts, “Analyzing Communal Life-Spans: A Dynamic Structural Approach,” Communal Societies 20 (2000), 13-25 Michael Barkun, “Communal Societies as Cyclical Phenomena,” Communal Societies 4 (1984), 35-48 Early Ventures EARLY UTOPIAN VISIONS AND EXPERIMENTS: Puritans and Moravians W. Thomas Mainwaring, “Communal Ideals, Worldly Concerns, and the Moravians of North Carolina, 1753-1772,” Communal Societies 6 (1986), 138-162 Ernest J. Green, “The Labadists of Colonial Maryland (1683-1722),” Communal Societies 8 (1988), 104-121 Utopian Ventures in the Early Republic MILLENNIALISTS AND RADICAL GERMAN PIETISTS: The Rappites of Harmony and the Separatists of Zoar Charles Nordhoff, “The Aurora and Bethel Communes,” American Utopias, 305-330 THE COMMUNITY OF TRUE INSPIRATION AT AMANA Herbert A.