Anarcho-Syndicalism 40

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

100 Spouting Anticollaborationist Slogans Against Those on the Left

THE LABOUR MOVEMENT AND THE LEFT IN THE UNITED STATES* Stanley Aronowitz During the 1960s and early 1970s, majority sentiment on the American left held that the American trade union movement had become a relatively conservative interest group. It fought within the Democratic Party, and in direct bargaining with corporations and government, for an increasingly narrow vision of its interests. For example, when confronted with the demands of blacks for full equality within the unions as much as within society as a whole, labour leaders responded with a dual position. The unions remained committed in general to civil rights at the legislative level, but were primarily protective of their members' immediate interests in higher pay and job security. When these interests were in conflict with the demand for full equality, some unions abandoned all but a legislative commitment to civil rights. On the question of the Vietnam war, most unions were either bellicose supporters of the Johnson policies, or remained silent, due either to the ambivalence of some leaders about the war or to unresolved debates among members. The left was aware that a section of the trade union leadership distinguished itself from the generally conservative policies of a section of industrial unions around the ILGWU, the building trades, and most of the old-line union leaders (all of whom grouped around George Meany). This more liberal wing of the labour leadership was led by the United Auto Workers (UAW) and included most of the old CIO unions except the Steelworkers, as well as some former AFL unions (notably, the Amalgamated Meatcutters, some sections of the Machinists, and the State, County, and Municipal Employees). -

THE BATTLE for SOCIALIST IDEAS in the 1980S

THE BATTLE FOR SOCIALIST IDEAS IN THE 1980s Stuart Hall I am honoured to be asked to give the first Fred Tonge lecture. I am pleased to be associated with the inspiration behind it, which is to commemorate the link between theory and practice, between socialist ideas and socialist politics, and thereby keep alive the memory of some- one who served the labour movement in both these ways throughout his life. Fred Tonge's commitment to socialism did not wane with age, as it has in so many other quarters. His commitment to socialist international- ism did not degenerate into that parochialism which so often besets our movement. He understood the absolute centrality of political education to the achievement of socialism. Those are very distinctive qualities and I want, in what follows to make a small contribution to their continuity. So I have chosen to talk about the struggle, the battle, for socialist ideas in the 1980s. First, I want to say something about the importance of ideological struggle. Thinking about the place and role of ideas in the construction of socialism, I would particularly emphasise the notion of struggle itself: ideology is a battlefield and every other kind of struggle has a stake in it. I want therefore to talk about the ideological pre-condition for socialist advance: the winning of a majority of the people-the working people of the society and their allies-to socialist ideas in the decades immediately ahead. I stress the centrality of the domain of the ideological-political ideas and the struggle to win hearts and minds to socialism-because I am struck again and again by the way in which socialists still assume that somehow socialism is inevitable. -

Referendum Move

THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SUNDAY, JUNE 8, 1913. 43 MANY ANSWER TO SAN MATEO ORGANIZES SPLENDID BAND FOR 1915 EXPOSITION. TARIFF FIGHT IS CALL OF VACATION NEAR TO CRISIS Streams of Summer Travel Senate Committee Will Give Bound for Springs, Shore Underwood Bill Severe and Mountain Test Before Caucus j Cuts Sched- Exodus From City to Re- Threatened in sorts and Country Is ules Indicate Struggle in Fairly Under Way Party Conference ' WASHINGTON, June 7.?B***for*» tns With fairly with us, the I'i the.summer tariffbill gets to the. senate streams /of travel to mountain and democratic?: caucus, where it be submitted to seashore may already be fully dis- .will the. most severe test It must meet be- cerned. \u25a0;-'\u25a0;"\u25a0?"''\u25a0 ;/:?.';> ,-; fore passage? it will have a?prelim< A familiar sight at the ticket offices its ; mary tryout .before the _senate finance is. father, with his fishing rod and the grips, medley committee that promises to be almost mother with' her of bun- equally? rigid.' '"."\u25a0, dles and (in many cases) big and little y Although v the subcommittees * have brother or sister tagging along with j been at .work' on -various schedules .'a; are to finish their baby to make up the family group, ; all month? and about work, said tonight that there their to school, it? was with- backs turned of- would \u25a0'". be opposition'\u25a0* byy democrats on f fice and workshop. " Diieclor Alois and his band of 40 pieces, organized under the auspices \u25a0of San Mateo merchants ,for the purpose of giving free 'open air concerts to ; the city's residents. -

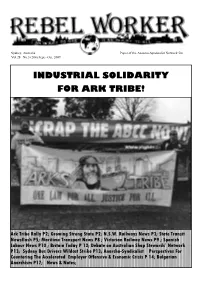

C:\Users\Mark\Documents\RWORKER\Rw Sept-Oct

Sydney, Australia Paper of the Anarcho-Syndicalist Network 50c Vol.28 No.3 (204) Sept.- Oct. 2009 INDUSTRIAL SOLIDARITY FOR ARK TRIBE! Ark Tribe Rally P2; Growing Strong State P2; N.S.W. Railways News P3; State Transit Newsflash P5; Maritime Transport News P8 ; Victorian Railway News P9 ; Spanish Labour News P10 ; Britain Today P 12; Debate on Australian Shop Stewards’ Network P13; Sydney Bus Drivers Wildcat Strike P13; Anarcho-Syndicalist Perspectives For Countering The Accelerated Employer Offensive & Economic Crisis P 14; Bulgarian Anarchism P17; News & Notes; 2 Rebel Worker suburbs in Adelaide. 200 people I think, destroying rights for the rest of us. The Rebel Worker is the bi-monthly maybe nearing 300? Judging by us having only time I felt like heckling was “like Paper of the A.S.N. for the propo- given out 50 leaflets to less than a quarter Ned Kelly, he’s been pushed around, gation of anarcho-syndicalism in of the crowd in about 2 minutes.5 political forced to do things he shouldn’t have to..” Australia. forces made an appearance, including the where I was too shy to heckle with “but he greens, democrats, an independent, ‘free still hasn’t shot any cops!” Unless otherwise stated, signed Australia party’(newly formed party of Would have got a laugh or two, especially Articles do not necessarily represent ‘motorcycle enthusiasts’(for anyone inter- from the “motorcycle enthusiasts”. Any- the position of the A.S.N. as a whole. nationally, bikers have been targeted by way.. to my understanding a motion was Any contributions, criticisms, letters absurd state powers recently, and have passed at the ACTU (Australian Council or formed a political party) and Socialist Al- of Trade Unions) (amazingly..) congress, Comments are welcome. -

Radicalism and the Limits of Reform: the Case of John Reed

DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY PASADENA, CALIFORNIA 91125 RADICALISM AND THE LIMITS OF REFORM: THE CASE OF JOHN REED Robert A. Rosenstone To be published in a volume of essays honoring George Mowry HUMANITIES WORKING PAPER 52 September 1980 ABSTRACT Poet, journalist, editorial bo,ard member of the Masses and founding member of the Communist Labor Party, John Reed is a hero in both the worlds of cultural and political radicalism. This paper shows how his development through pre-World War One Bohemia and into left wing politics was part of a larger movement of middle class youngsters who were in that era in reaction against the reform mentality of their parent's generation. Reed and his peers were critical of the following, common reformist views: that economic individualism is the engine of progress; that the ideas and morals of WASP America are superior to those of all other ethnic groups; that the practical constitutes the best approach to social life. By tracing Reed's development on these issues one can see that his generation was critical of a larger cultural view, a system of beliefs common to middle class reformers and conservatives alike. Their revolt was thus primarily cultural, one which tested the psychic boundaries, the definitions of humanity, that reformers shared as part of their class. RADICALISM AND THE LIMITS OF REFORM: THE CASE OF JOHN REED Robert A. Rosenstone In American history the name John Reed is synonymous with radicalism, both cultural and political. Between 1910 and 1917, the first great era of Bohemianism in this country, he was one of the heroes of Greenwich Village, a man equally renowned as satiric poet and tough-minded short story writer; as dashing reporter, contributing editor of the Masses, and co-founder of the Provinceton Players; as lover of attractive women like Mabel Dodge, and friend of the notorious like Bill Haywood, Enma Goldman, Margaret Sanger and Pancho Villa. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

'The Italians and the IWMA'

Levy, Carl. 2018. ’The Italians and the IWMA’. In: , ed. ”Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth”. The First International in Global Perspective. 29 The Hague: Brill, pp. 207-220. ISBN 978-900-4335-455 [Book Section] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/23423/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] chapter �3 The Italians and the iwma Carl Levy Introduction Italians played a significant and multi-dimensional role in the birth, evolution and death of the First International, and indeed in its multifarious afterlives: the International Working Men's Association (iwma) has also served as a milestone or foundation event for histories of Italian anarchism, syndicalism, socialism and communism.1 The Italian presence was felt simultaneously at the national, international and transnational levels from 1864 onwards. In this chapter I will first present a brief synoptic overview of the history of the iwma (in its varied forms) in Italy and abroad from 1864 to 1881. I will then exam- ine interpretations of aspects of Italian Internationalism: Mazzinian Repub- licanism and the origins of anarchism, the Italians, Bakunin and interactions with Marx and his ideas, the theory and practice of propaganda by the deed and the rise of a third-way socialism neither fully reformist nor revolutionary, neither Marxist nor anarchist. -

Revolutionary Syndicalist Opposition to the First World War: A

Re-evaluating syndicalist opposition to the First World War Darlington, RR http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0023656X.2012.731834 Title Re-evaluating syndicalist opposition to the First World War Authors Darlington, RR Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/19226/ Published Date 2012 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Re-evaluating Syndicalist Opposition to the First World War Abstract It has been argued that support for the First World War by the important French syndicalist organisation, the Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT) has tended to obscure the fact that other national syndicalist organisations remained faithful to their professed workers’ internationalism: on this basis syndicalists beyond France, more than any other ideological persuasion within the organised trade union movement in immediate pre-war and wartime Europe, can be seen to have constituted an authentic movement of opposition to the war in their refusal to subordinate class interests to those of the state, to endorse policies of ‘defencism’ of the ‘national interest’ and to abandon the rhetoric of class conflict. This article, which attempts to contribute to a much neglected comparative historiography of the international syndicalist movement, re-evaluates the syndicalist response across a broad geographical field of canvas (embracing France, Italy, Spain, Ireland, Britain and America) to reveal a rather more nuanced, ambiguous and uneven picture. -

Libertarianism Karl Widerquist, Georgetown University-Qatar

Georgetown University From the SelectedWorks of Karl Widerquist 2008 Libertarianism Karl Widerquist, Georgetown University-Qatar Available at: https://works.bepress.com/widerquist/8/ Libertarianism distinct ideologies using the same label. Yet, they have a few commonalities. [233] [V1b-Edit] [Karl Widerquist] [] [w6728] Libertarian socialism: Libertarian socialists The word “libertarian” in the sense of the believe that all authority (government or combination of the word “liberty” and the private, dictatorial or democratic) is suffix “-ian” literally means “of or about inherently dangerous and possibly tyrannical. freedom.” It is an antonym of “authoritarian,” Some endorse the motto: where there is and the simplest dictionary definition is one authority, there is no freedom. who advocates liberty (Simpson and Weiner Libertarian socialism is also known as 1989). But the name “libertarianism” has “anarchism,” “libertarian communism,” and been adopted by several very different “anarchist communism,” It has a variety of political movements. Property rights offshoots including “anarcho-syndicalism,” advocates have popularized the association of which stresses worker control of enterprises the term with their ideology in the United and was very influential in Latin American States and to a lesser extent in other English- and in Spain in the 1930s (Rocker 1989 speaking countries. But they only began [1938]; Woodcock 1962); “feminist using the term in 1955 (Russell 1955). Before anarchism,” which stresses person freedoms that, and in most of the rest of the world (Brown 1993); and “eco-anarchism” today, the term has been associated almost (Bookchin 1997), which stresses community exclusively with leftists groups advocating control of the local economy and gives egalitarian property rights or even the libertarian socialism connection with Green abolition of private property, such as and environmental movements. -

KARL MARX Peter Harrington London Peter Harrington London

KARL MARX Peter Harrington london Peter Harrington london mayfair chelsea Peter Harrington Peter Harrington 43 dover street 100 FulHam road london w1s 4FF london sw3 6Hs uk 020 3763 3220 uk 020 7591 0220 eu 00 44 20 3763 3220 eu 00 44 20 7591 0220 usa 011 44 20 3763 3220 www.peterharrington.co.uk usa 011 44 20 7591 0220 Peter Harrington london KARL MARX remarkable First editions, Presentation coPies, and autograPH researcH notes ian smitH, senior sPecialist in economics, Politics and PHilosoPHy [email protected] Marx: then and now We present a remarkable assembly of first editions and presentation copies of the works of “The history of the twentieth Karl Marx (1818–1883), including groundbreaking books composed in collaboration with century is Marx’s legacy. Stalin, Mao, Che, Castro … have all Friedrich Engels (1820–1895), early articles and announcements written for the journals presented themselves as his heirs. Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher and Der Vorbote, and scathing critical responses to the views of Whether he would recognise his contemporaries Bauer, Proudhon, and Vogt. them as such is quite another matter … Nevertheless, within one Among this selection of highlights are inscribed copies of Das Kapital (Capital) and hundred years of his death half Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei (Communist Manifesto), the latter being the only copy of the the world’s population was ruled Manifesto inscribed by Marx known to scholarship; an autograph manuscript leaf from his by governments that professed Marxism to be their guiding faith. years spent researching his theory of capital at the British Museum; a first edition of the His ideas have transformed the study account of the First International’s 1866 Geneva congress which published Marx’s eleven of economics, history, geography, “instructions”; and translations of his works into Russian, Italian, Spanish, and English, sociology and literature.” which begin to show the impact that his revolutionary ideas had both before and shortly (Francis Wheen, Karl Marx, 1999) after his death. -

ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z

1111 ~~ I~ I~ II ~~ I~ II ~IIIII ~ Ii II ~III 3 2103 00341 4723 ELIZABETH GURLEY FLYNN Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER A Communist's Fifty Yea1·S of ,tV orking-Class Leadership and Struggle - By Elizabeth Gurley Flynn NE'V CENTURY PUBLISIIERS ABOUT THE AUTHOR Elizabeth Gurley Flynn is a member of the National Com mitt~ of the Communist Party; U.S.A., and a veteran leader' of the American labor movement. She participated actively in the powerful struggles for the industrial unionization of the basic industries in the U.S.A. and is known to hundreds of thousands of trade unionists as one of the most tireless and dauntless fighters in the working-class movement. She is the author of numerous pamphlets including The Twelve and You and Woman's Place in the Fight for a Better World; her column, "The Life of the Party," appears each day in the Daily Worker. PubUo-hed by NEW CENTURY PUBLISH ERS, New York 3, N. Y. March, 1949 . ~ 2M. PRINTED IN U .S .A . Labor's Own WILLIAM Z. FOSTER TAUNTON, ENGLAND, ·is famous for Bloody Judge Jeffrey, who hanged 134 people and banished 400 in 1685. Some home sick exiles landed on the barren coast of New England, where a namesake city was born. Taunton, Mass., has a nobler history. In 1776 it was the first place in the country where a revolutionary flag was Bown, "The red flag of Taunton that flies o'er the green," as recorded by a local poet. A century later, in 1881, in this city a child was born to a poor Irish immigrant family named Foster, who were exiles from their impoverished and enslaved homeland to New England. -

The Formation of the Communist Party, 1912–21

chapter 1 The Formation of the Communist Party, 1912–21 The Bolsheviks envisioned the October Revolution as the first in a series of pro- letarian revolutions. The Communist or Third International was to be a new, revolutionary international born from the wreckage of the social-democratic Second International. They sought to forge this international with what they saw as the best elements of the international working-class movement, those that had not betrayed socialism by supporting the war. The Comintern was to be a complete and definite break with the social-democratic politics of the Second International. In the face of the support of World War I by many labour and social-democratic leaders, significant sections of the workers’ movement rallied to the Bolsheviks.1 This was most pronounced in Italy and France, but in the United States as well the first Bolshevik supporters came from the left wing of the labour movement. In much of Europe, the social-democratic leaders either openly supported the militarism and imperialism of their ‘own’ ruling classes (such as when the German Social Democratic representatives voted for war credits on 4 August 1914) or (in the case of Karl Kautsky) provided ‘left’ cover to open social-chauvinists. In the United States, which entered the war late in the day, the party leadership as a whole opposed the war. However, the American socialist movement was still infected with electoral reformism, and a signifi- cant number of influential Socialists downplayed the party’s official opposi- tion to the war. This chapter examines how the American Communist movement devel- oped out of these antecedents.