Making-Room.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multilingual -2010 Resource Directory & Editorial Index 2009

Language | Technology | Business RESOURCE ANNUAL DIRECTORY EDITORIAL ANNUAL INDEX 2009 Real costs of quality software translations People-centric company management 001CoverResourceDirectoryRD10.ind11CoverResourceDirectoryRD10.ind1 1 11/14/10/14/10 99:23:22:23:22 AMAM 002-032-03 AAd-Aboutd-About RD10.inddRD10.indd 2 11/14/10/14/10 99:27:04:27:04 AMAM About the MultiLingual 2010 Resource Directory and Editorial Index 2009 Up Front new year, and new decade, offers an optimistically blank slate, particularly in the times of tightened belts and tightened budgets. The localization industry has never been affected quite the same way as many other sectors, but now that A other sectors begin to tentatively look up the economic curve towards prosperity, we may relax just a bit more also. This eighth annual resource directory and index allows industry professionals and those wanting to expand business access to language-industry companies around the globe. Following tradition, the 2010 Resource Directory (blue tabs) begins this issue, listing compa- nies providing services in a variety of specialties and formats: from language-related technol- ogy to recruitment; from locale-specifi c localization to educational resources; from interpreting to marketing. Next come the editorial pages (red tabs) on timeless localization practice. Henk Boxma enumerates the real costs of quality software translations, and Kevin Fountoukidis offers tips on people-centric company management. The Editorial Index 2009 (gold tabs) provides a helpful reference for MultiLingual issues 101- 108, by author, title, topic and so on, all arranged alphabetically. Then there’s a list of acronyms and abbreviations used throughout the magazine, a glossary of terms, and our list of advertisers for this issue. -

Squatting – the Real Story

Squatters are usually portrayed as worthless scroungers hell-bent on disrupting society. Here at last is the inside story of the 250,000 people from all walks of life who have squatted in Britain over the past 12 years. The country is riddled with empty houses and there are thousands of homeless people. When squatters logically put the two together the result can be electrifying, amazing and occasionally disastrous. SQUATTING the real story is a unique and diverse account the real story of squatting. Written and produced by squatters, it covers all aspects of the subject: • The history of squatting • Famous squats • The politics of squatting • Squatting as a cultural challenge • The facts behind the myths • Squatting around the world and much, much more. Contains over 500 photographs plus illustrations, cartoons, poems, songs and 4 pages of posters and murals in colour. Squatting: a revolutionary force or just a bunch of hooligans doing their own thing? Read this book for the real story. Paperback £4.90 ISBN 0 9507259 1 9 Hardback £11.50 ISBN 0 9507259 0 0 i Electronic version (not revised or updated) of original 1980 edition in portable document format (pdf), 2005 Produced and distributed by Nick Wates Associates Community planning specialists 7 Tackleway Hastings TN34 3DE United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)1424 447888 Fax: +44 (0)1424 441514 Email: [email protected] Web: www.nickwates.co.uk Digital layout by Mae Wates and Graphic Ideas the real story First published in December 1980 written by Nick Anning by Bay Leaf Books, PO Box 107, London E14 7HW Celia Brown Set in Century by Pat Sampson Piers Corbyn Andrew Friend Cover photo by Union Place Collective Mark Gimson Printed by Blackrose Press, 30 Clerkenwell Close, London EC1R 0AT (tel: 01 251 3043) Andrew Ingham Pat Moan Cover & colour printing by Morning Litho Printers Ltd. -

The Psytrance Party

THE PSYTRANCE PARTY C. DE LEDESMA M.Phil. 2011 THE PSYTRANCE PARTY CHARLES DE LEDESMA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of East London for the degree of Master of Philosophy August 2011 Abstract In my study, I explore a specific kind of Electronic Dance Music (EDM) event - the psytrance party to highlight the importance of social connectivity and the generation of a modern form of communitas (Turner, 1969, 1982). Since the early 90s psytrance, and a related earlier style, Goa trance, have been understood as hedonist music cultures where participants seek to get into a trance-like state through all night dancing and psychedelic drugs consumption. Authors (Cole and Hannan, 1997; D’Andrea, 2007; Partridge, 2004; St John 2010a and 2010b; Saldanha, 2007) conflate this electronic dance music with spirituality and indigene rituals. In addition, they locate psytrance in a neo-psychedelic countercultural continuum with roots stretching back to the 1960s. Others locate the trance party events, driven by fast, hypnotic, beat-driven, largely instrumental music, as post sub cultural and neo-tribal, representing symbolic resistance to capitalism and neo liberalism. My study is in partial agreement with these readings when applied to genre history, but questions their validity for contemporary practice. The data I collected at and around the 2008 Offworld festival demonstrates that participants found the psytrance experience enjoyable and enriching, despite an apparent lack of overt euphoria, spectacular transgression, or sustained hedonism. I suggest that my work adds to an existing body of literature on psytrance in its exploration of a dance music event as a liminal space, redolent with communitas, but one too which foregrounds mundane features, such as socialising and pleasure. -

Acts of Dissent Against 'Mass Tourism' in Barcelona[Version 1; Peer

Open Research Europe Open Research Europe 2021, 1:66 Last updated: 30 SEP 2021 RESEARCH ARTICLE A summer of phobias: media discourses on ‘radical’ acts of dissent against ‘mass tourism’ in Barcelona [version 1; peer review: 2 approved, 1 approved with reservations] Alexander Araya López Department of Linguistics and Comparative Cultural Studies, Ca' Foscari University of Venice, Venezia, Venezia, 30123, Italy v1 First published: 10 Jun 2021, 1:66 Open Peer Review https://doi.org/10.12688/openreseurope.13253.1 Latest published: 10 Jun 2021, 1:66 https://doi.org/10.12688/openreseurope.13253.1 Reviewer Status Invited Reviewers Abstract In the summer of 2017, the young group Arran coordinated a series of 1 2 3 protests in Barcelona and other Spanish cities to denounce the negative effects of global mass tourism. These acts of dissent fueled a version 1 heated public debate in both Spanish and international press, mainly 10 Jun 2021 report report report due to the ‘radical’ tactics employed by the demonstrators. Following the narratives about these protest acts across a diversity of media 1. Freya Higgins-Desbiolles , University of outlets, this article identifies the complex power struggles between the different actors involved in the discussion on the benefits and South Australia, Adelaide, Australia externalities of global mass tourism, offering an extensive analysis of the political uses of the term ‘turismofobia’ (tourismphobia) and a 2. Neil Hughes , University of Nottingham, revisited interpretation of the notion of the ‘protest paradigm’. This Nottingham, UK qualitative analysis was based on more than 700 media texts (including news articles, op eds and editorials) collected through the 3. -

Rethinking Intergenerational Housing

Rethinking intergenerational housing This summary has been published following a year-long grant-funded research project to rethink intergenerational housing. Our goal has been to explore whether and how people of all ages and backgrounds can live independent lives in housing that supports the sharing of skills, knowledge and experience. These following pages outline our findings; if you want to find out more, please get in touch. An project by with Index An project by with People are increasingly living isolated lives; a key way to tackle this is to build housing that brings together social benefit, design and management. Housing in the UK is highly segregated, inflexible and often unsuitable, creating 1. Social benefit emerging crises in special needs and care, affordability and loneliness. These have major impacts on people’s health, increasing costs for society. The term intergenerational housing has been widely used to describe schemes that bring together younger and older people to share activities and to socialise. They have been found to deliver great benefits through ousin tackling isolation, but tend to be ad-hoc and encounter practical difficulties. Our aim has been to learn from these examples and to rethink how they could work as part of a strategic option for mainstream housing. 2. Dsin 3. Management The key to this is to consider social benefit, design and management together at the outset. This research was made possible by Innovate UK and a range of partnering housing and policy organisations. An project by with Research map Policy constraints opportunities This map shows the areas covered by our research project. -

Spatialities of Prefigurative Initiatives in Madrid

Spatialities of Prefigurative Initiatives in Madrid María Luisa Escobar Hernández Erasmus Mundus Master Course in Urban Studies [4Cities] Master’s Thesis Supervisor: Dr. Manuel Valenzuela. Professor Emeritus of Human Geography, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. Second Reader: Dr. Nick Schuermans. Postdoctoral Researcher, Brussels Centre for Urban Studies. 1st September 2018 Acknowledgments First and foremost I would like to thank all the activists who solidarily shared their stories, experiences, spaces, assemblies and potlucks with me. To Viviana, Alma, Lotta, Araceli, Marta, Chefa, Esther, Cecilia, Daniel Revilla, Miguel Ángel, Manuel, José Luis, Mar, Iñaki, Alberto, Luis Calderón, Álvaro and Emilio Santiago, all my gratitude and appreciation. In a world full of injustice, inequality, violence, oppression and so on, their efforts shed light on the possibilities of building new realities. I would also like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Manuel Valenzuela for the constant follow-up of this research process, his support in many different ways, his permanent encouragement and his guidance. Likewise, to Dr. Casilda Cabrerizo for her orientation on Madrid’s social movements scene, her expert advice on the initiatives that are being developed in Puente de Vallecas and for providing me with the contacts of some activists. After this intense and enriching two-year Master’s program, I would also like to thank my 4Cities professors. I am particularly grateful to Nick Schuermans who introduced me to geographical thought. To Joshua Grigsby for engaging us to alternative city planning. To Martin Zerlang for his great lectures and his advice at the beginning of this thesis. To Rosa de la Fuente, Marta Domínguez and Margarita Baraño for their effort on showing us the alternative face of Madrid. -

Pdf at OAPEN Library

Tweets and the Streets Gerbaudo T02575 00 pre 1 30/08/2012 11:04 Gerbaudo T02575 00 pre 2 30/08/2012 11:04 TWEETS AND THE STREETS Social Media and Contemporary Activism Paolo Gerbaudo Gerbaudo T02575 00 pre 3 30/08/2012 11:04 First published 2012 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Distributed in the United States of America exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010 Copyright © Paolo Gerbaudo 2012 The right of Paolo Gerbaudo to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3249 9 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3248 2 Paperback ISBN 978 1 8496 4800 4 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 8496 4802 8 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 8496 4801 1 EPUB eBook Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Designed and produced for Pluto Press by Chase Publishing Services Ltd Typeset from disk by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Simultaneously printed digitally by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham, UK and Edwards Bros in the United States of America Gerbaudo T02575 00 pre 4 30/08/2012 11:04 -

RADIO BULLETIN Radio Bulletin Is Een Maandelijkse Uitgave Van Uitgeverij De Muiderkring BV, Inhoud Nijverheidswerf 17-21, Bussum

Meer prestaties De K 40 /end t vet dev en ontvangt duidelgker ah andere antennen Wii i«eien dat dit zo #s Wi| hebben dii met 771 CB ers. zoals U, getest, en d«l een taar iang Meer flexibiliteit 'J hunt u« K 40 overal aanbrengen Zm past op • r rijtuig dat U /ult be/itien, ingesloten terreinvoertuigen, bover op dakgoi spiegel vlaktes. in het bagagenet. in koffers in lut tp daken. ders. en/ Meer kwaliteit Zi| is een US kwaliteitsmerk Zi| is niet geprodu Japan Ze is vervaardigd in de USA m een amer en duurde' matenaal gemaakt. en door vaklui d IWgffrTtW; vendien werd /i| direkt in de USA ontworpen ELECTROmca® Netigeraet VoiistatMiisiert Kurzschlussgesichert Pr.maer 220V Wechselspannyng Aus Sekundaer 13.8V Gie.chstrom, 5/7 Ampe ELECTRONICA DVP 127 Met onze nettoestellen bent U alle stroomproblemen kwijt. Euratronica Vertriebsgesellschaft fur Electronic mbH Exclusive agency Donatusstrasse 109 D-5000 Koln 71 (Pesch) Tel.: 0221 / 590 20 77 Telex: 888 52 63 ___for Europe I RADIO BULLETIN Radio Bulletin is een maandelijkse uitgave van uitgeverij De Muiderkring BV, Inhoud Nijverheidswerf 17-21, Bussum. Postadres: Postbus 10, 1400 AA Bussum (Holland), 1 De U-matic VO-2630 videocassetterecorder Tel.: 02159-31851, Telex: 15171, Postgiro 83214. 6 Video- en beeldplaatpresentatie Firato 1980 Bank: Amro-bank, Weesp, rek. nr. 48.49.54.563. 7 Vertragingsschakeling voorauto Redactie binnenverlichting hoofdredacteur: W. Hesselink Omslagfoto: eindredacteur: A. J. Vlaswinkel Dit zijn de letter- en redacteuren: 8 Frontplaat voor de Toonfietsderjaren D. J. F. Scheper cijfersymbolen van teletekst en P. G. J. de Beer (CB) tachtig' een voorbeeld van een grafische H. -

Making Space

Alternative radical histories and campaigns continuing today. Sam Burgum November 2018 Property ownership is not a given, but a social and legal construction, with a specific history. Magna Carta (1215) established a legal precedent for protecting property owners from arbitrary possession by the state. ‘For a man’s home is his ASS Archives ASS castle, and each man’s home is his safest refuge’ - Edward Coke, 1604 Charter of the Forest (1217) asserted the rights of the ‘commons’ (i.e. propertyless) to access the 143 royal forests enclosed since 1066. Enclosure Acts (1760-1870) enclosed 7million acres of commons through 4000 acts of parliament. My land – a squatter fable A man is out walking on a hillside when suddenly John Locke (1632-1704) Squatting & Trespass Context in Trespass & Squatting the owner appears. argued that enclosure could ‘Get off my land’, he yells. only be justified if: ‘Who says it’s your land?’ demands the intruder. • ‘As much and as good’ ‘I do, and I’ve got the deeds to prove it.’ was left to others; ‘Well, where did you get it from?’ ‘From my father.’ • Unused property could be ‘And where did he get it from?’ forfeited for better use. ‘From his father. He was the seventeenth Earl. The estate originally belonged to the first Earl.’ This logic was used to ‘And how did he get it?’ dispossess indigenous people ‘He fought for it in the War of the Roses.’ of land, which appeared Right – then I’ll fight you for it!’ ‘unused’ to European settlers. 1 ‘England is not a Free people till the poor that have no land… live as Comfortably as the landlords that live in their inclosures.’ Many post-Civil war movements and sects saw the execution of King Charles as ending a centuries-long Norman oppression. -

Revue Européenne Des Sciences Sociales, XL-124

Revue européenne des sciences sociales European Journal of Social Sciences XL-124 | 2002 Histoire, philosophie et sociologie des sciences Pour un état des lieux des rapports établis et des problèmes ouverts. XIXe colloque annuel du Groupe d’Étude « Pratiques Sociales et Théories » Gérald Berthoud et Giovanni Busino (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ress/568 DOI : 10.4000/ress.568 ISSN : 1663-4446 Éditeur Librairie Droz Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 août 2002 ISBN : 2-600-00806-3 ISSN : 0048-8046 Référence électronique Gérald Berthoud et Giovanni Busino (dir.), Revue européenne des sciences sociales, XL-124 | 2002, « Histoire, philosophie et sociologie des sciences » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 01 décembre 2009, consulté le 04 décembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ress/568 ; DOI : https://doi.org/ 10.4000/ress.568 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 4 décembre 2020. © Librairie Droz 1 Actes édités par Gérald Berthoud et Giovanni Busino avec la collaboration rédactionnelle de Daniela Cerqui, Farinaz Fassa, Sabine Kradolfer, Frédéric Ischy et Olivier Simoni Revue européenne des sciences sociales, XL-124 | 2002 2 SOMMAIRE Avant-propos La connaissance a-t-elle un sujet ? Un essai pour repenser l’individu Catherine Chevalley Normes, communauté et intentionnalité Pierre Jacob Un modèle polyphonique en épistémologie sociale Croyances individuelles, pluralité des voix et consensus en matière scientifique39-58 Alban Bouvier La question du réalisme scientifique : un problème épistémologique central Angèle Kremer Marietti Objectivité et subjectivité en science. Quelques aperçus Jacqueline Feldman La notion de révolution scientifique aujourd’hui Gérard Jorland Hétérogénéité ontologique du social et théorie de la description. -

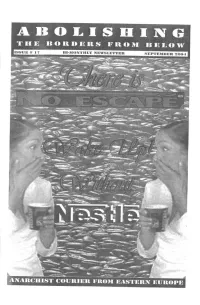

Abolishing the Borders from Below Page 2

•TMj^ii-oftmmmm vROmim 12I^«Pw editorial Abolishing the Borders from Below page 2 There is a justifiable need to abolish the borders between nations, societies, cultures and whatever else Distt separates and defines us. In order that this process does not lead to the formation of new borders or other types of segregation, like those established by elitist institutions such as the EU, NATO or UN, it has to be done from We are looking below, by the people. There is an enduring need to immediately abolish all states, governments and authoritarian ready to distribut regular basis in th institutions so that communities based on common values such as freedom, respect, cooperation and solidarity southern Europe) well available. Con above mentioned values. In order to push that process forward with support for the development of the anarchist movement over the borders we have created ... wielkowitsc More complex ij Free copi Free copies go to all There are many reasons why it is necessary to put out this type of publication on a regular basis. There are a large librarys in Eastern Ei number of anarchist groups in EE which could operate much more effectively with a continual exchange of ideas, with us) as well as t supply a postal adn tactics, experiences and materials with similarly minded groups from all over Europe and the World. It is clear that print by ourselves 1 many western activists are also interested in the ideas and actions of the "eastern anarchists". We believe it to be and there are some necessary to tighten the cooperation between east and west in resisting Fortress Europe, the globalization of the more copies by world economy, and above all capitalism and it's effects on our life. -

Boom Festival | Rehearsing the Future

Boom festival | Rehearsing the Future Music and the Prefiguration of Change by Saul Roosendaal 5930057 Master’s thesis Musicology August 2016 supervised by dr. Barbara Titus University of Amsterdam Boom festival | Rehearsing the future Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 1. A Transformational Festival ................................................................................................. 9 1.1 Psytrance and Celebration ........................................................................................... 9 1.2 Music and Culture ..................................................................................................... 12 1.3 Dance and Musical Embodiment .............................................................................. 15 1.4 Art, Aesthetics and Spirituality ................................................................................. 18 1.5 Summary ................................................................................................................... 21 2. Music and Power: Prefigurating Change ........................................................................... 23 2.1 Education: The Liminal Village as Forum ................................................................ 25 2.1.1 Drugs and Policies .........................................................................................