A Durable Struggle for Social Autonomy in Urban Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disponible En Formato

Consumir menos, vivir mejor Ideas prácticas para un consumo más consciente 3 4 Toni Lodeiro Consumir menos, vivir mejor Ideas prácticas para un consumo más consciente 5 Portada y diseño colección: Esteban Montorio Autor dibujo página 3: Pello Irizar Huguet Edición: Editorial Txalaparta s.l. Navaz y Vides 1-2 Apdo. 78 31300 Tafalla NAFARROA Tfno. 948 703934 Fax 948 704072 [email protected] www.txalaparta.com Primera edición de Txalaparta Tafalla, mayo de 2008 Reconocimiento-No comercial-Compartir bajo la misma licencia 2.5 España Licencia completa en: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/es/ © Txalaparta para la presente edición Realización gráfica nabarreria.com Impresión Gráficas Lizarra I.S.B.N. 978-84-8136-515-3 Depósito legal NA-1645-08 6 Gracias A todas las personas que escogemos en la vida ser parte de la solución y no del problema.* A todas las personas que hemos ayudado a que existan las ideas prácticas, reflexiones, empresas, asociaciones... que reseña este libro. A quienes habeis aportado a estas páginas apoyo, ánimos, sugerencias, correcciones... Si hiciese una lista sería larguísima y seguro me olvidaría de alguien, así que puedes poner tu nombre aquí A Anna, sobran los motivos. Ás amigas e amigos con quen compartín nestes últimos anos as experiencias que me impulsaron a escribir este libro: Xurxo, Merce, Pablo, Sergio, Chema, Antonio, Gema, Lucha, Sabela, Juan... A Sumendi y sus gentes. A Lakabe y sus habitantes. A la gente del CRIC y la revista Opcions. Aos meus amigos “de sempre” e á miña familia, por seguirnos gozando e aturando, despois de tantos anos. -

El Movimiento Okupa: Prácticas Y Contextos Sociales

¿Dónde están… M1 (filmar) 16/6/14 10:27 Página 3 ¿Dónde están… M1 (filmar) 16/6/14 10:27 Página 4 RAMÓN ADELL ARGILÉS PROFESOR TITULAR DE CAMBIO SOCIAL EN LA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS POLÍTICAS Y SOCIOLOGÍA DE LA UNED. [email protected] HTTP://WWW.UNED.ES/DPTO- SOCIOLOGIA-I/ADELL/WEBRAMON.HTM JAVIER ALCALDE VILLACAMPA LICENCIADO EN CIENCIAS POLÍTICAS Y DE LA ADMINISTRACIÓN. DOCTORANDO EN TEORÍA POLÍTICA, TEORÍA DEMOCRÁTICA Y ADMINISTRACIÓN PÚBLICA EN LA UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID. [email protected] JAUME ASENS LLODRÀ LICENCIADO EN DERECHO Y FILOSOFÍA. DOCTORANDO EN CIENCIAS POLÍTICAS Y SOCIALES EN LA UNIVERSIDAD POMPEU FABRA DE BARCELONA. [email protected] ROBERT GONZÁLEZ GARCÍA LICENCIADO EN CIENCIAS POLÍTICAS Y DE LA ADMINISTRACIÓN Y EN SOCIOLOGÍA. DOCTORANDO EN EL INSTITUTO DE GOBIERNO Y POLÍTICAS PÚBLICAS DE LA UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BARCELONA. [email protected] VIRGINIA GUTIÉRREZ BARBARRUSA LICENCIADA EN CIENCIAS POLÍTICAS Y SOCIOLOGÍA Y MASTER EN INVESTIGACIÓN, GESTIÓN Y DESARROLLO LOCAL POR LA UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID. [email protected] TOMÁS HERREROS SALA PROFESOR EN LA UNIVERSIDAD DE BARCELONA Y EN LA UNIVERSITAT OBERTA DE CATALUNYA. [email protected] MARTA LLOBET ESTANY PROFESORA DE SOCIOLOGÍA EN LA ESCUELA DE TRABAJO SOCIAL DE LA UNIVERSIDAD DE BARCELONA. [email protected] MARINA MARINAS SÁNCHEZ PROFESORA TITULAR DE SOCIOLOGÍA DE LA DESVIACIÓN Y DE ESTRUCTURA DE LA SOCIEDAD CONTEMPORÁNEA EN LA UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID. [email protected] MIGUEL MARTÍNEZ LÓPEZ LICENCIADO EN SOCIOLOGÍA Y DOCTOR EN CIENCIAS POLÍTICAS. INVESTIGADOR EN LA FACULTAD DE SOCIOLOGÍA, UNIVERSIDAD DE LA CORUÑA. [email protected] HANS PRUIJT PROFESOR DE SOCIOLOGÍA EN LA ERASMUS UNIVERSITEIT RÓTTERDAM. -

(2020) European Squatters' Movements

9781138494930PRE.3D 3 [1–20] 22.10.2019 8:01AM Routledge Handbook of Contemporary European Social Movements Protest in Turbulent Times Edited by Cristina Flesher Fominaya and Ramón A. Feenstra 9781138494930PRE.3D 4 [1–20] 22.10.2019 8:01AM First published 2020 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2020 selection and editorial matter, Cristina Flesher Fominaya and Ramón Feenstra; individual chapters, the contributors The right of Cristina Flesher Fominaya and Ramón A. Feenstra to be identified as the authors of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record has been requested for this book ISBN: 978-1-138-49493-0 hbk ISBN: 978-1-351-02518-8 ebk Typeset in Bembo by Swales & Willis, Exeter, Devon, UK 9781138494930C11.3D 155 [155–167] 22.10.2019 2:39AM 11 European squatters’ movements and the right to the city Miguel A. -

Making-Room.Pdf

Making R o o m : Cultural Published by Other Forms and the Journal of Aesthetics and Protest Production in Occupied Spaces 2 Making R o o m : Cultural Production in Occupied Spaces Edited by Alan Moore and Alan Smart 3 Making Room: Cultural Production in Occupied Spaces 8 Preface DENMARK Miguel Ángel Martínez López 84 Christiania: How They Do It 12 Whether You Like It or Not and for How Long Alan W. Moore Jordan Zinovich 20 Beneath the Bored Walk, the 95 Christiania Art and Culture Beach Britta Lillesøe, Christiania Stevphen Shukaitis Cultural Association 24 Mental Prototypes and 98 Bolsjefabrikken: Autonomous Monster Institutions: Culture in Copenhagen Some Notes by Way of an Tina Steiger Introduction Universidad Nómada 104 On the Youth House Protests and the Situation in 34 Squatting For Justice: Copenhagen Bringing Life To The City Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen Miguel Ángel Martínez López UNITED KINGDOM NETHERLANDS 116 Partisan Notes Towards 42 Creativity and the Capitalist a History of UK Squatting City (1980 to the Present) Tino Buchholz x-Chris 52 The Autonomous Zone 122 “Our Enemy is Dreamless (de Vrije Ruimte) Sleep!” On the Cultic Vincent Boschma Creation of an Autonomous Network 58 Squatting and Media: Kasper Opstrup An Interview With Geert Lovink GERMANY Alan Smart 130 We Don´t Need No Landlords 72 The Emerging Network of ... Squatting in Germany from Temporary Autonomous 1970 to the Present Zones (TAZ) Azomozox Aja Waalwijk 136 Autonomy! Ashley Dawson 4 Contents 148 Stutti 206 Telestreet: Pirate Proxivision Sarah Lewison Patrick Nagle 160 Regenbogen Fabrik – the 216 MACAO: Establishing Rainbow Factory Conflicts Towards a New Alan W. -

Fighting for Spaces, Fighting for Our Lives

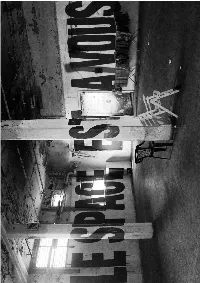

Squatting Everywhere Kollective (SqEK) Ed. Fighting for spaces, fighting for our lives: Squatting movements today Dieses Buch wird unter den Bedingungen einer Creative Commons License veröffentlicht: Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Germany License (abrufbar unter www. creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/legalcode). Squatting Everywhere Kollective (SqEK) Ed. Fighting for spaces, fighting for our lives: Squatting movements today 1. Auflage 2018 ISBN 978-3-942885-90-4 edition assemblage Postfach 27 46 D- 48041 Münster [email protected] | www. edition-assemblage.de Mitglied der Kooperation book:fair Eigentumsvorbehalt: Dieses Buch bleibt Eigentum des Verlages, bis es der gefangenen Person direkt ausgehändigt wurde. Zur-Habe-Nahme ist keine Aushändigung im Sinne dieses Vorbehalts. Bei Nichtaushändigung ist es unter Mitteilung des Grundes zurückzusenden. Umschlag: Foto: Oliver Feldhaus/Umbruch Bildarchiv Satz: Squatting Everywhere Kollective (SqEK) Lektorat: Squatting Everywhere Kollective (SqEK) Druck: Squatting Everywhere Kollective (SqEK) Printed in Croatia 2018 Gefördert von der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung. Instead of an Introduction SqEK-Kollective 2 Voices of Resistance - About the Refugee Movement in Kreuzberg (Berlin) 4 Napuli Paul Langa You Can’t Evict a Movement - From the Rise of the Refugee Movement in Germany 16 to the Practice of Squatting Colectivo Hinundzurück (Berlin) Overflowing the walls. The squatting is on the paths. 38 Elisabeth Lorenzi Hidden Histories of Resistance - The Diverse Heritages -

Contraflow 21 Feb Mar 1997

3 Febuary - March 1 997 B M flf ’ Number 21 IHf Si your donations keep us contraFLOW” 18 FREE |56a Infoshop, 56 Crampton St, London SE17, U.K. e-mail : [email protected] This time last year clearance work started on the controversial A34 Newbury Bypass. Imaginative direct action successfully As Promised blacked the first week of work, and the resulting headlines drew many people to Newhury to challenge the government+s road- building programme. Over the next few months full-on evictions (with the help of scab climbers, now ostracised' by the rest of the British climb- ing scene) cleared most of the camps which had spung up along the nine miles of route. Repeated front-line trashing, and the notorious "Newbury sausage" bail-conditions which came as standard with many of the hundreds of 'Aggravated Trespass' arrests, meant that once the trees were gone many protestors moved on to other places. Daily (and nightly!) action continued throughout the summer, Workfare but January's "Reunion Rampage" was the first time many people had returned to the town to see the full scale of the damage, and in large enough numbers to affect it. The nine miles Not content with hassling us with the Job Seekers Allow- is now covered by (razor-topped) fenced compounds, guarded by ance, or introducing proposals to reduce money to those the badly-paid minions of Pinkertons security. of us who are single parents or on Housing Benefit, good Approx. 1 50 turned up in time for the Friday morning old Johnny Major and his cronies are now forcing compound invasions.