Self-Help Housing: Could It Play a Greater Role?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking Intergenerational Housing

Rethinking intergenerational housing This summary has been published following a year-long grant-funded research project to rethink intergenerational housing. Our goal has been to explore whether and how people of all ages and backgrounds can live independent lives in housing that supports the sharing of skills, knowledge and experience. These following pages outline our findings; if you want to find out more, please get in touch. An project by with Index An project by with People are increasingly living isolated lives; a key way to tackle this is to build housing that brings together social benefit, design and management. Housing in the UK is highly segregated, inflexible and often unsuitable, creating 1. Social benefit emerging crises in special needs and care, affordability and loneliness. These have major impacts on people’s health, increasing costs for society. The term intergenerational housing has been widely used to describe schemes that bring together younger and older people to share activities and to socialise. They have been found to deliver great benefits through ousin tackling isolation, but tend to be ad-hoc and encounter practical difficulties. Our aim has been to learn from these examples and to rethink how they could work as part of a strategic option for mainstream housing. 2. Dsin 3. Management The key to this is to consider social benefit, design and management together at the outset. This research was made possible by Innovate UK and a range of partnering housing and policy organisations. An project by with Research map Policy constraints opportunities This map shows the areas covered by our research project. -

Hidden Histories of Resistance

Hidden Histories In essence, without squatting we would have remained isolated as gay men living in our individual shabby bedsit or flats or of Resistance The Diverse Heritage of Squatting in England houses. Squatting enabled us to come together collectively to break down that isolation and produced some of the most productive political campaigning and radical theatre, not to mention a shot at non-bourgeois, non-straight ways of living. – Ian Townson text liberated from the landlords at crimethinc.com by oplopanax publishing Over the past few years, there has been a push to criminalize squatting across Western Europe. But in a time of increasing economic instability, can governments succeed in suppressing squatting? What is at stake here? This article reviews the background and contemporary context of squat- ting in England, beginning after the Second World War and comparing the current movement to its counterparts on mainland Europe. It touches on many stories: migrants squatting to build a life safe from fascist attacks, gay activists finding spaces in which to build up a scene, vibrant and insurgent squatted areas, single-issue campaigns occupying as a direct action tactic, and anti-capitalist groups setting up social centers. We hope this text will help those in present-day struggles to root themselves in the heritage of previous movements. Online version with photos and video available at cwc.im/uksquat The UK Social Centre Network (in 2006) has warned that “Britain is now at the centre of a perfect storm of housing problems. High and rising rents, the cripplingly high costs of getting on the housing ladder, and the lowest peacetime building figures since the 1920s have all combined with a prolonged economic downturn to increase the pressure on families.” Another commentator ends a long analysis by sug- gesting that we will soon be witnessing the return of slums in the UK. -

Imagining the Future City: London 2062

IMAGINING THE FUTURE CITY: LONDON 2062 www.shahrsazionline.com Edited by Sarah Bell and James Paskins SUSTAINABLE CITIES SERIES Imagining the Future City: London 2062 Edited by Sarah Bell and James Paskins www.shahrsazionline.com ]u[ ubiquity press London Published by Ubiquity Press Ltd. Gordon House 29 Gordon Square London WC1H 0PP www.ubiquitypress.com Text © The Authors 2013 First published 2013 Cover Illustrations by Edward Manley Front: ‘Clusters of Activity in Minicab Journeys across London’ Back: ‘Mapping Minicab Flows across London’ Printed in the UK by Lightning Source Ltd. ISBN (paperback): 978-1-909188-18-1 ISBN (EPUB): 978-1-909188-19-8 ISBN (PDF): 978-1-909188-20-4 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/bag This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. Suggested citation: Bell, S and Paskins, J (eds.) 2013 Imagining the Future City: London 2062. London: Ubiquity Press. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/bag A minor correction was made to this book soon after publication. On p.77, the sentence “When refurbishing, covering up solid walls with insulation can significantly increase the available thermal mass…”, was amended to “When refurbishing, covering up solid walls with insulation can significantly decrease the available thermal mass…”. -

Eight Temporary Autonomous Art Events in London

UtilisING SPACe ruimte utilitizieren ate Aout 2o13 8 brighton squat trial updates This zine has had a few missed deadlines and one was the trial back in April of the three squatters arrested in September last year, just after squatting in residential buildings. They were the first people to plead not guilty to the new offence and we wanted to make a big deal out of it. In the end, no-one else really cared but the public gallery was packed every day as we watch the magistrates struggle to understand what the fuck was happening. The police lied as they always do but looked rather uncomfortable in their new role as property guardians. Their amateur video interview with the wanker entrusted with keeping the building empty was cute but two squatters walked free, since there wasn’t any evidence that they were living in the building. The case was then adjourned and unfortunately (also rather amazingly), the third squatter was later found guilty, the sole extra evidence against him being that a cop said he lived there!! It was really a bullshit judgement which I hope a judge will overturn. The appeal is in motion, it’s been adjourned once but should happen on October 30/31. On the Friday night, Dillinger Escape Plan are playing Concorde with Maybeshewill (who I’m listening to now as it happens) so hopefully we’ll get the conviction overturned and a useful precedent set regarding how residential and living are defined legaly. That would be a good start to the weekend Halloween festivities. -

Summer 2016.Pdf

Organise! AF Contacts Keep in mind that we have members in most areas of the Issue 86 – Summer 206 UK and so if you do not see a group listed below then please contact us as a general enquiry or the appropriate Organise! is the magazine of the Anarchist Federation regional secretary. (AF). As anarchist communists we fight for a world All General Enquires without leaders, where power is shared equally amongst communities, and people are free to reach Post: BM ANARFED, their full potential. We do this by supporting working London, WC1N 3XX, class resistance to exploitation and oppression, England, UK organise alongside our neighbours and workmates, Email: [email protected] host informative events, and produce publications that Web: http://afed.org.uk help make sense of the world around us. Alba (Scotland) Organise! is published twice/year with the aim to Regional Secretary provide a clear anarchist viewpoint on contemporary [email protected] issues and to initiate debate on ideas not normally Aberdeen (in formation) covered in agitational papers. To meet this target, we [email protected] positively solicit contributions from our readers. We Edinburgh & the Lothians will try to print any article that furthers the objectives of [email protected] anarchist communism. If you’d like to write something Glasgow for us, but are unsure whether to do so, then feel free to [email protected] contact us through any of the details below. Inverness and the Highlands [email protected] The articles in this issue do not represent the collective viewpoint of the AF unless stated as such. -

Better Streets Delivered 2 Better This Document Is a Research Document and Its Content Does Not Represent Adopted Policy

Better 2 Delivered Streets This document is a research document and its content does not represent adopted policy. All errors and omissions remain our own. Better Streets Delivered 2 Learning from completed schemes Learning from completed schemes from completed Learning © Transport for London Windsor House 42-50 Victoria Street London SW1H 0TL April 2017 tfl.gov.uk TR1510933_Better Streets_2017_Spine_AW.indd 1 07/04/2017 09:57 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION We are transforming the way we manage and understand our streets. However, Better Streets Delivered Learning from completed schemes Better 10 36 population estimates indicate that London needs to absorb approximately Streets Delivered 03 Introduction STREETS JUNCTIONS AND LINKS 1.5 million more people by 2031. A population infl ux of this magnitude puts Learning from completed schemes 04 Benefi ts of Healthy Streets 12 Hoe Street, Walthamstow Town 38 Euston Circus increasing pressure on our streets, requiring them to perform more effi ciently to 04 Better Streets initiative Centre 42 Holborn Circus transport additional goods and people within limited space. In this context we are 06 Categorising the schemes 14 Leyton High Road 44 Leonard Circus already changing the way we are thinking about our streets. 08 Better Streets Delivered 16 Royal College Street A growing body of evidence shows the important role that streets play in our daily 18 Victoria Road and The Battis, lives. Well-designed streets help to improve the local economy, encourage people MAYOR Romford Transport for London OF LONDON 01 20 Wood Street Town Centre 46 to use more healthy modes of transport, and foster social connections. -

Visioning a Sustainable Energy Future: the Case of Urban Food-Growing

Theory Culture & Society VISIONING A SUSTAINABL E ENERGY FUTURE - THE CASE OF URBAN FOOD GROWING earlier title: BACKCASTING FOR A SUSTAINABLE ENERGY FUTUREFor – THE Peer CASE OF URBANReview FOOD-GROWING Journal: Theory Culture & Society Manuscript ID: 13-129-SIESoc.R1 Manuscript Type: SI - Special Issue Energising Society Key Words: food, future, contemporary activism, utopia, city, space, ecology We outline a future where society re-energises itself, in the sense both of recapturing creative dynamism, and of applying creativity to meeting physical energy needs. Both require us to embrace self-organising properties, whether in nature or society. We critically appraise backcasting as a methodology for visioning, arguing that backcasting’s potential for radical, outside-the-box thinking is restricted unless it contemplates a break with class society, connects with existing grassroots struggles Abstract: (notably over land) and dialogues with utopian socialist tradition. We develop a case study of food, starting from the physical parameters of combatting the entropy expressed in the loss of soil structure, and apply this to urban food-growing. Drawing upon ‘real utopias’ of existing practice, the paper proposes a threefold categorisation: subsistence plots, an urban forest, and an ultra-high productivity sector. We emphasise the emergent properties of such a complex system characterised by the ‘free energy’ of societal self-organisation. Page 1 of 30 Theory Culture & Society 1 2 3 4 BACKCASTING FOR A SUSTAINABLE ENERGY FUTURE – THE CASE OF URBAN FOOD-GROWING 5 6 7 8 9 I: BACKCASTING, A CRITICAL ANALYSIS 10 11 12 Widely-used definitions of backcasting emphasise its distinction from forecasting or scenario- 13 building (Wearerising, 2009). -

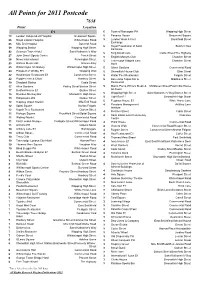

Points Asked How Many Times Today

All Points for 2011 Postcode 7638 Point Location E1 6 Town of Ramsgate PH Wapping High Street 73 London Independent Hospital Beaumont Square 5 Panama House Beaumont Square 66 Royal London Hospital Whitechapel Road 5 London Wool & Fruit Brushfield Street Exchange 65 Mile End Hospital Bancroft Road 5 Royal Foundation of Saint Butcher Row 59 Wapping Station Wapping High Street Katharine 42 Guoman Tower Hotel Saint Katharine’s Way 5 King David Lane Cable Street/The Highway John Orwell Sports Centre Tench Street 27 5 English Martyrs Club Chamber Street News International Pennington Street 26 5 Travelodge Aldgate East Chamber Street 25 Wiltons Music Hall Graces Alley Hotel 25 Whitechapel Art Gallery Whitechapel High Street 5 Albert Gardens Commercial Road 24 Prospect of Whitby PH Wapping Wall 5 Shoreditch House Club Ebor Street 22 Hawksmoor Restaurant E1 Commercial Street 5 Water Poet Restaurant Folgate Street 22 Poppies Fish & Chips Hanbury Street 5 Barcelona Tapas Bar & Middlesex Street 19 Shadwell Station Cable Street Restaurant 17 Allen Gardens Pedley Street/Buxton Street 5 Marco Pierre White's Steak & Middlesex Street/East India House 17 Bedford House E1 Quaker Street Alehouse Wapping High Street Saint Katharine’s Way/Garnet Street 15 Drunken Monkey Bar Shoreditch High Street 5 Light Bar E1 Shoreditch High Street 13 Hollywood Lofts Quaker Street 5 Pegasus House E1 White Horse Lane 12 Stepney Green Station Mile End Road 5 Pensions Management Artillery Lane 12 Spital Square Norton Folgate 4 Institute 12 Kapok Tree Restaurant Osborn Street -

Harleyford Road Vauxhall Grove

Aerial view of the site and surrounding area Images of the existing site Welcome Welcome to this public exhibition on the future Newsletter Mini-Series of St Anne’s Catholic Settlement, Harleyford Road. Newsletter #1 | October 2019 | Education We have also been engaging with St Anne’s Catholic Settlement is working with the community via a mini-series Notting Hill Genesis to provide a new facility for of newsletters, each focusing on important existing community uses, as well as a particular theme relating to the deliver much-needed new homes. Settlement, including education, religion, community, and housing We know there is a well-established community ST ANNE’S CATHOLIC SETTLEMENT, VAUXHALL within the local area. As our plans for the Dear Neighbour, St. Anne’s Catholic Settlement is working in collaboration with Notting Hill Genesis on plans to improve the service we can offer our users by building a brand new facility on the site of 40-46 Harleyford Road in Vauxhall. We are a charitable organisation that achieves its objectives through a number of activities including Settlement evolve, we have been engaging with the provision of affordable accommodation to a range of charities. The Settlement has been in the same building for over 100 years, but unfortunately for a long time it has not been fit for purpose. the community, to hear their thoughts on the The planned redevelopment aims to secure our long-term future. With new facilities, we can continue to offer important services, functions and activities that matter so much to our community. This is the first in a series of newsletters where we talk about who we are, what scheme. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Planning Applications Committee

b PLANNING APPLICATIONS COMMITTEE Date: Tuesday 11 November 2014 Time: 7.00 pm Venue: Room 8, Lambeth Town Hall, Brixton Hill, SW2 1RW Copies of agendas, reports, minutes and other attachments for the Council’s meetings are available on the Lambeth website. www.lambeth.gov.uk/moderngov Members of the Committee Councillor Malcolm Clark, Councillor Bernard Gentry, Councillor Diana Morris (Chair), Councillor Sally Prentice, Councillor Joanne Simpson, Councillor Clair Wilcox (Deputy Chair) and Councillor Sonia Winifred Substitute Members Councillor Liz Atkins, Councillor Anna Birley, Councillor Jennifer Brathwaite, Councillor Tim Briggs, Councillor Jane Edbrooke, Councillor Nigel Haselden, Councillor Robert Hill, Councillor Jack Hopkins, Councillor Louise Nathanson and Councillor Jane Pickard Further Information If you require any further information or have any queries please contact: Katy Shaw, Telephone: 020 7926 2225; Email: [email protected] Members of the public are welcome to attend this meeting and the Town Hall is fully accessible. If you have any specific needs please contact Facilities Management (020 7926 1010) in advance. Queries on reports: Please contact report authors prior to the meeting if you have questions on the reports or wish to inspect the background documents used. The contact details of the report author is shown on the front page of each report. @LBLdemocracy on Twitter http://twitter.com/LBLdemocracy or use #Lambeth Lambeth Council – Democracy Live on Facebook http://www.facebook.com/ AGENDA PLEASE NOTE THAT THE ORDER OF THE AGENDA MAY BE CHANGED AT THE MEETING Page Nos. 1. Declaration of Pecuniary Interests Under Standing Order 4.4, where any councillor has a Disclosable Pecuniary Interest (as defined in the Members’ Code of Conduct (para. -

Squatted Social Centres in London

Article Squatted Social Centres in London Contention: The Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Protest Peer Reviewed Journal Vol. 4(1-2), pp. 109-127 (2016) ISSN 2330-1392 © 2016 The Authors SQUATTED SOCIAL CENTRES IN LONDON: TEMPORARY NODES OF RESISTANCE TO CAPITALISM E.T.C.DEE INDEPENDENT SCHOLAR Abstract This article assesses squatted social centres in London as a means to understand the cycles, contexts and institutionalisation processes of the local squatters movement. This diffuse social movement had its heyday in the late 1970s and early 1980s when there were 30,000 squatters and still exists today despite squatting in residential buildings being criminalised in 2012. Analysis is based on a database of 245 social centres, which are examined in terms of duration, time period, type of building and location. Important centres are briefly profiled and important factors affecting the squatters movement are examined, in particular institutionalisation, gentrification and criminalisation. Keywords Social centres; urban squatting; squatters movement; London; social movements Corresponding author: E.T.C.Dee, Email: [email protected] Thanks to all the people who helped me with this project, plus the various libraries and infoshops I worked in. All errors and omissions are mine. This article was written as part of the MOVOKEUR research project CSO2011-23079 (The Squatters Movement in Spain and Europe: Contexts, Cycles, Identities and Institutionalization, funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation 2012-2014). Editorial Note: This aticle is not part of the special issue. 109 Contention Vol. 4 Issue 1-2 October 2016 n this article, I intend to analyse the contexts, cycles and institutionalisation processes of the Ipolitical squatters movement in London. -

Neoism, Plagiarism and Praxis

Neoism, Plagiarism & Praxis by Stewart Home AK IUd"1#1 EDINBURGH & SAN FRANCISCO. 1995 Neoism. Plagiarism & Praxis by Stewart Home A elP catalogue for this book is available from me British Library A catalogue entry for this book is available from the Library of Congress Much of the material included in this volume has previously appeared elsewhere. Published in 1995 by AK Press Edinburgh and San Francisco AK Press, 22 Lutton Place, Edinburgh, Scotland, EH8 9PE, UK. AK Press, P. O. Box 40682, San Francisco, CA 94140-0682, USA. ISBN 1 87317633 3 Stewart Home can be contacted directly at BM Senior, London WC 1 N 3XX, UK (full address) or via the publishers. Printed in the Gre at Britain. Contents 5 Introduction PART I From Plagiarism to Praxis I I Karen Eliot 12 Demolish Serious Culture 13 Desire in ruins 15 The art of ideology and the ideology of art 19 Beneath the cobble stones, the sewers 20 From Dada to Class War: ten minutes that shook cheque book journalism 21 From author to authority: Pepsi versus Coke 22 Artists placement and the end of art 23 Neoism 25 Art Strikes 26 Art Strike 1990-93 28 Work 29 Oppositional culture and cultural opposition 36 Language, identity and the avant-garde 40 Aesthetics and resistance: totality reconsidered PART 2 From Dialectics to Stasis 45 Ruins of glamour/glamour of ruins 47 Desire in Ruins - statement 48 The role of Sight in recent cultural history 49 Plagiarism as negation in culture 51 Plagiarism 52 Multiple names 53 Soon... 54 A short rant concerning our cultural condition PART 3 Neoist Reprise