Download Press Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martin Moszkowicz Filmographie

FILMOGRAPHIE MARTIN MOSZKOWICZ FILMOGRAPHIE MARTIN MOSZKOWICZ JAHR TITEL REGIE 2022 Liebesdings Anika Decker EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Der Nachname Sönke Wortmann EXECUTIVE PRODUCER 2021 Welcome to Raccoon City Johannes Roberts EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Contra Sönke Wortmann EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Caveman Laura Lackmann EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Tides Tim Fehlbaum EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Ostwind - Der große Orkan Lea Schmidbauer CO-PRODUZENT The Foundation Mike P. Nelson EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Monster Hunter Paul W.S. Anderson EXECUTIVE PRODUCER 2 020 Drachenreiter Tomer Eshed EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Black Beauty Ashley Avis EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Berlin, Berlin Franziska Meyer Price CO-PRODUZENT Das geheime Leben der Bäume Jörg Adolph EXECUTIVE PRODUCER 2019 Das perfekte Geheimnis Bora Dagtekin EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Eine ganz heiße Nummer 2.0 Rainer Kaufmann CO-PRODUZENT Die drei !!! Viviane Andereggen CO-PRODUZENT The Silence John R. Leonetti EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Der Fall Collini Marco Kreuzpaintner EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Ostwind – Aris Ankunft Theresa von Eltz CO-PRODUZENT Polar Jonas Akerlund EXECUTIVE PRODUCER FILMOGRAPHIE MARTIN MOSZKOWICZ JAHR TITEL REGIE 2018 Der Vorname Sönke Wortmann EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Fünf Freunde und das Tal der Dinosaurier Mike Marzuk CO-PRODUZENT Asphaltgorillas Detlev Buck EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Verpiss Dich, Schneewittchen Cüneyt Kaya EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Nur Gott kann mich richten Özgur Yildrim CO-PRODUZENT 2017 Dieses bescheuerte Herz Marc Rothemund PRODUZENT Das Pubertier Leander Haußmann EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Tigermilch Ute Wieland EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Ostwind – Aufbruch nach Ora Katja von Garnier CO-PRODUZENT Axolotl Overkill Helene Hegemann EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Tiger Girl Jakob Lass EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Jugend ohne Gott Alain Gsponer EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Timm Thaler oder das verkaufte Lachen Andreas Dresen EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Shadowhunters (TV) McG u.a. PRODUZENT Resident Evil: The Final Chapter Paul W.S. -

Rainer Werner Fassbinder Amor Y Rabia Coordinado Por Quim Casas

Rainer Werner Fassbinder Amor y rabia Coordinado por Quim Casas Colección Nosferatu Editan: E. P. E. Donostia Kultura Teatro Victoria Eugenia Reina Regente 8 20003 Donostia / San Sebastián Tf.: + 34 943 48 11 57 [email protected] www.donostiakultura.eus Euskadiko Filmategia – Filmoteca Vasca Edificio Tabakalera Plaza de las Cigarreras 1, 2ª planta 20012 Donostia / San Sebastián Tf.: + 34 943 46 84 84 [email protected] www.filmotecavasca.com Distribuye: UDL Libros Tf.: + 34 91 748 11 90 www.udllibros.com © Donostia Kultura, Euskadiko Filmategia – Filmoteca Vasca y autores ISBN: 978-84-944404-9-6 Depósito legal: SS-883-2019 Fuentes iconográficas: Rainer Werner Fassbinder Foundation, Goethe-Institut Madrid, StudioCanal, Beta Cinema, Album Diseño y maquetación: Ytantos Imprime: Michelena Artes Gráficas Foto de portada: © Rainer Werner Fassbinder Foundation Las amargas lágrimas de Petra von Kant © Rainer© Fassbinder Werner Foundation SUMARIO CONTEXTOS Presentación: amor y rabia. Quim Casas .......................................... 17 No había casa a la que volver. Fassbinder y el Nuevo Cine Alemán. Violeta Kovacsics ......................................... 31 En la eternidad de una puesta de sol. Carlos Losilla ........................... 37 El teatro, quizá, no fue un mero tránsito. Imma Merino ...................... 47 GÉNEROS, SOPORTES, FORMATOS, ESTILOS Experimentar con Hollywood y criticar a la burguesía Los primeros años del cine de Fassbinder Israel Paredes Badía ..................................................................... 61 Más frío que la muerte. El melodrama según Fassbinder: un itinerario crítico. Valerio Carando .............................................. 71 Petra, Martha, Effi, Maria, Veronika... El cine de mujeres de Fassbinder. Eulàlia Iglesias ........................................................ 79 Atención a esas actrices tan queridas. La puesta en escena del cuerpo de la actriz. María Adell ................................................ 89 Sirk/Fassbinder/Haynes. El espejo son los otros. -

HOW to BERLINALE Una Breve Guía Para Presentar Tus Películas

HOW TO BERLINALE Una breve guía para presentar tus películas SECCIONES Y PROGRAMAS International Competition cuenta con unas 25 películas en la sección Oficial (dentro y fuera de la competición). Los premios son decididos por un Jurado Internacional. Contacto: [email protected] Berlinale Special y Berlinale Special Gala son programas comisariados por el director del festival. Sólo son accesibles con invitación y no acepta inscripciones. Se presentan nuevas producciones extraordinarias y películas de o sobre personalidades del mundo del cine, las cuales están estrechamente ligadas al festival. Contacto: [email protected] Panorama dentro de la Sección oficial (no competitiva) presenta nuevos trabajos de directores de renombre; muestra óperas primas y otros nuevos descubrimientos. La selección de los filmes da una visión global de las tendencias del arte cinematográfico mundial. Contacto: [email protected] Forum se centra en las nuevas tendencias en el cine mundial, formas de narración prometedoras y nuevas voces. Forum también destaca debuts de directores así como la innovación en los trabajos de jóvenes cineastas. El Forum Expanded se dedica a los límites entre cine y artes visuales. Es un programa comisariado por el Forum al que sólo se accede con invitación y no aceptan inscripciones. Contacto: [email protected] Generation abre Berlinale a los jóvenes y niños. Las competiciones de Kplus y 14plus no sólo presentan producciones realizadas especialmente para niños y jóvenes; también muestran películas dirigida a los jóvenes y a público de otras edades debido a su forma y contenido. El marketing potencial de estas películas se ve, de este modo, potenciado. Contacto: [email protected] Berlinale Shorts cuenta con cortometrajes de cineastas y artistas innovadores. -

Sixth German Film Festival

IN BETWEEN WORLDS – R12 Award at Cannes and was an international success, even spawning a Hollywood remake. SIXTH GERMAN FILM FESTIVAL (Zwischen Welten) Since the mid-1990s, Wenders has distinguished himself as a non- 19th – 23rd November 2014 Director: Feo Aladag, fiction filmmaker, directing several highly acclaimed documentaries, Organised by the 103 min., 2014 most notably Buena Vista Social Club (1999) and PINA (2011), both of German-Maltese Circle Festivals: Berlinale 2014 which brought him Oscar nomination. in collaboration with the Goethe Institute GOETHE-INSTITUT GOETHE-INSTITUT (in competition) Jesper, a German Armed Forces soldier THE AMERICAN FRIEND Wednesday, 19th November Venue: St James Cavalier, Valletta signs up for another mission in the (Der amerikanische Freund) “Age of Cannibals” 19.00 hrs war-torn country of Afghanistan. He 1977, 123 min. - at 17.00 hrs (“Zeit der Kannibalen”) and his squad are assigned the task (based in the novel “Ripley’s game” by of guarding a small village outpost Patricia Highsmith) Thursday, 20th November Venue: St James Cavalier, Valletta from increasing Taliban influence. Together with Tarik, their young “Finsterworld” 19.00 hrs and inexperienced interpreter, they try to win the trust of the village Jonathan, formerly a restorer, now making picture frames, lives in Hamburg. He suffers “Stations of the Cross” 21.00 hrs community and the allied Afghani militia. The difference between the (“Kreuzweg”) two worlds, however, is immense. When Tarik and his sister, Nala, from leukaemia and knows that there is no escape for him. Tom Ripley, an American are being menaced by the Taliban, Jesper comes into conflict with Friday, 21st November Venue: St James Cavalier, Valletta both his conscience and the orders he receives: should he help his art dealer, makes him a very doubtful offer: “Westen” 19.00 hrs interpreter, Tarik, in a life-threatening situation or should he follow he is to commit a murder in Paris. -

Press Kit the CAPTAIN Film by Robert

Press kit THE CAPTAIN DER HAUPTMANN – Original title Written and directed by Robert Schwentke Produced by Filmgalerie 451 Saarbrücker Straße 24, 10405 Berlin Tel. +49 (0) 30 - 33 98 28 00 Fax +49 (0) 30 - 33 98 28 10 [email protected] www.filmgalerie451.de In co-production with Alfama Films and Opus Film THE CAPTAIN / DER HAUPTMANN directed by Robert Schwentke World Premiere at Toronto International Film Festival — Special Presentations Screening dates Press & Industry 1 09/07/17 3:00PM Scotiabank 14 (307) DCP 4K (D-Cinema) Public 1 09/09/17 3:15PM TIFF Bell Lightbox DCP 4K (D-Cinema) Cinema 1 (523) Public 2 09/11/17 4:15PM Scotiabank 10 (228) DCP 4K (D-Cinema) Press & Industry 2 09/13/17 11:30AM Scotiabank 8 (183) DCP 4K (D-Cinema) Public 3 09/16/17 3:30PM Scotiabank 14 (307) DCP 4K (D-Cinema) Press contact in Toronto Sunshine Sachs: Josh Haroutunian / [email protected] o: 323.822.9300 / c: 434.284.2076 Press photos Press photos you will get on our website (press) with the password: willkommen www.filmgalerie451.de World Sales Alfama Films www.alfamafilms.com Table of contents – Synopsis short – Synopsis long – Biography Robert Schwentke – Filmography Robert Schwentke – Director’s statement – Interview with director Robert Schwentke about THE CAPTAIN – Film information – Credits – About the Cast – Background information THE CAPTAIN – Willi Herold, a German life — The true story behind THE CAPTAIN – Nazi perpetrator, center-stage — by Olaf Möller 2 THE CAPTAIN / DER HAUPTMANN directed by Robert Schwentke Synopsis short In the last, desperate moments of World War II, a young German soldier fighting for survival finds a Nazi captain’s uniform. -

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

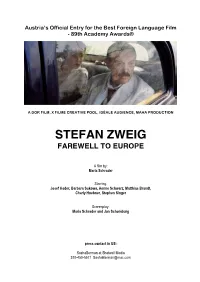

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant, -

30. World Film Festival Montréal Winner Bavarian Film Award

WINNER BAVARIAN FILM AWARD SPECIAL JURY PRIZE 2006 SÉLECTION OFFICIELLE 30. WORLD FILM FESTIVAL MONTRÉAL IN COMPETITION WORLD PREMIÉRE MONTREAL WORLD FILMFESTIVAL 2006 . FESTIVAL DES FILMS DU MONDE 2006 Screenings August 31, 2006 11:30 L’écran VISA au CINÉMA IMPÉRIAL August 31, 2006 19:00 THÉATRE MAISONNEUVE September 01, 2006 16:30 L’écran VISA au CINÉMA IMPÉRIAL PRESS Ana Radica Presse Organisation Herzog-Wilhelmstr. 27 80331 München Germany TEL. 0049.89.2366120 EMAIL [email protected] 02 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 01 Short comment on „WARCHILD“ 04 02 Synopsis 05 03 Reviews 05 04 Main roles 06 05 Minor roles 07 06 Teamlist 08 07 Short summary 09 08 Directors comments 10 - 11 09 Characterization of the main fi gures 12 10 Biography Cast 13 - 16 11 Biography Crew 16 - 21 12 Shooting time, locations, technical dates 22 03 1 SHORT COMMENTS ON „WARCHILD“ Balkan Blues Trilogy II Warchild featuring Labina Mitevska and Katrin Sass (GOOD BYE, LENIN) and directed by acclaimed fi lmmaker Christian Wagner (WALLERS LAST TRIP/TRANSATLANTIS/GHETTO KIDS), presented by the prestigious 30. WORLD FILM FESTIVAL MONTRÉAL in competition. Christian Wagner‘s second part of the BALKAN BLUES TRILOGY stars Labina Mitevska and Katrin Sass. Mitevska (EUROPEAN SHOOTINGSTAR 1998) made her debut in BEFORE THE RAIN, a fi lm that won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, and has appeared in several Michael Winterbottom fi lms (WELCOME TO SARAJEVO and I WANT YOU). Katrin Sass, too, has a remarkable career to look back on. At the Berlin International Film Festival in 1982, she received the Silver Bear for her performance in ON PROBATION and she also was awarded the German Film Award for her part in HEIDE M. -

Last Tango in Paris (1972) Dramas Bernardo Bertolucci

S.No. Film Name Genre Director 1 Last Tango in Paris (1972) Dramas Bernardo Bertolucci . 2 The Dreamers (2003) Bernardo Bertolucci . 3 Stealing Beauty (1996) H1.M Bernardo Bertolucci . 4 The Sheltering Sky (1990) I1.M Bernardo Bertolucci . 5 Nine 1/2 Weeks (1986) Adrian Lyne . 6 Lolita (1997) Stanley Kubrick . 7 Eyes Wide Shut – 1999 H1.M Stanley Kubrick . 8 A Clockwork Orange [1971] Stanley Kubrick . 9 Poison Ivy (1992) Katt Shea Ruben, Andy Ruben . 1 Irréversible (2002) Gaspar Noe 0 . 1 Emmanuelle (1974) Just Jaeckin 1 . 1 Latitude Zero (2000) Toni Venturi 2 . 1 Killing Me Softly (2002) Chen Kaige 3 . 1 The Hurt Locker (2008) Kathryn Bigelow 4 . 1 Double Jeopardy (1999) H1.M Bruce Beresford 5 . 1 Blame It on Rio (1984) H1.M Stanley Donen 6 . 1 It's Complicated (2009) Nancy Meyers 7 . 1 Anna Karenina (1997) Bernard Rose Page 1 of 303 1 Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (1964) Russ Meyer 9 . 2 Vixen! By Russ Meyer (1975) By Russ Meyer 0 . 2 Deep Throat (1972) Fenton Bailey, Randy Barbato 1 . 2 A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE (1951) Elia Kazan 2 . 2 Pandora Peaks (2001) Russ Meyer 3 . 2 The Lover (L'amant) 1992 Jean-Jacques Annaud 4 . 2 Damage (1992) Louis Malle 5 . 2 Close My Eyes (1991) Stephen Poliakoff 6 . 2 Casablanca 1942 H1.M Michael Curtiz 7 . 2 Duel in the Sun (film) (1946) I1.M King Vidor 8 . 2 The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) H1.M David Lean 9 . 3 Caligula (1979) Tinto Brass 0 . -

Skruger2006.Pdf (1.625Mb)

Die letzten Tage Adolf Hitlers --- Eine Darstellung für das 21. Jahrhundert in Oliver HIRSCHBIEGEL s Der Untergang by Stefanie Krüger A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in German Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2006 © Stefanie Krüger 2006 Author’s declaration for electronic submission of a thesis I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. iii Abstract The film Der Untergang (2004), directed by Oliver HIRSCHBIEGEL and written and produced by Bernd EICHINGER , is based on Joachim FEST ’s historical monograph Der Untergang (2002) and Traudl JUNGE ’s and Melissa MÜLLER ’s Bis zur letzten Stunde (2003). Taking place in April, 1945, the movie depicts the last days of Adolf Hitler and his staff in the ‘Führerbunker’. The appearance of the film sparked wide-spread controversy concerning the propriety of Germans illuminating this most controversial aspect of their history. Specifically, the debate centred on the historical accuracy of the film and the dangers associated with the filmmakers’ goal of portraying Hitler not as a caricature or one-sided figure but rather as a complete human being whose troubles and human qualities might well earn the sympathy of the viewers. After surveying a variety of films that portray Adolf Hitler, the thesis analyses Der Untergang by focusing first on the cinematic and narrative aspects of the film itself and then on the figure of Hitler. -

German Videos - (Last Update December 5, 2019) Use the Find Function to Search This List

German Videos - (last update December 5, 2019) Use the Find function to search this list Aguirre, The Wrath of God Director: Werner Herzog with Klaus Kinski. 1972, 94 minutes, German with English subtitles. A band of Spanish conquistadors travels into the Amazon jungle searching for the legendary city of El Dorado, but their leader’s obsessions soon turn to madness.LLC Library CALL NO. GR 009 Aimée and Jaguar DVD CALL NO. GR 132 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul Director: Rainer Werner Fassbinder. with Brigitte Mira, El Edi Ben Salem. 1974, 94 minutes, German with English subtitles. A widowed German cleaning lady in her 60s, over the objections of her friends and family, marries an Arab mechanic half her age in this engrossing drama. LLC Library CALL NO. GR 077 All Quiet on the Western Front DVD CALL NO. GR 134 A/B Alles Gute (chapters 1 – 4) CALL NO. GR 034-1 Alles Gute (chapters 13 – 16) CALL NO. GR 034-4 Alles Gute (chapters 17 – 20) CALL NO. GR 034-5 Alles Gute (chapters 21 – 24) CALL NO. GR 034-6 Alles Gute (chapters 25 – 26) CALL NO. GR 034-7 Alles Gute (chapters 9 – 12) CALL NO. GR 034-3 Alpen – see Berlin see Berlin Deutsche Welle – Schauplatz Deutschland, 10-08-91. [ Opening missing ], German with English subtitles. LLC Library Alpine Austria – The Power of Tradition LLC Library CALL NO. GR 044 Amerikaner, Ein – see Was heißt heir Deutsch? LLC Library Annette von Droste-Hülshoff CALL NO. GR 120 Art of the Middle Ages 1992 Studio Quart, about 30 minutes. -

DVD-Liste SPIELFILME

DVD-Liste Der Bibliothek des Goethe-Instituts Krakau SPIELFILME Abgebrannt / [Darsteller:] Maryam Zaree, Tilla Kratochwil, Lukas Steltner... Regie & Buch: Verena S. Freytag. Kamera: Ali Olcay Gözkaya. Musik: Roland Satterwhite Frankfurt: PFMedia, 2012.- Bildtonträger.- 1 DVD-Video (Ländercode 0, 103 Min.) : farb. Sprache: dt. - Untertitel: engl., franz.- FSK-Freigabe ab 12 Jahren. - Spielfilm. Deutschland. 2010 The Adventures of Werner Holt / Darsteller: Klaus-Peter Thiele, Manfred Karge, Arno Wyzniewski ... Kamera: Rolf Sohre. Musik: Gerhard Wohlgemuth. Drehbuch: Claus Küchenmeister... Regie: Joachim Kunert. [Nach dem Roman von Dieter Noll] - 1 DVD (163 Min.) : s/w. Dolby digital EST: Die@Abenteuer des Werner Holt <dt.> Sprache: dt. - Untertitel: eng. - Extras: Biografien und Filmografien. - Spielfilm, Literaturverfilmung. DDR. 1964 Abfallprodukte der Liebe / Ein Film von Werner Schroeter. Mit Anita Cerquetti, Martha Mödl, Rita Gorr... Berlin: Filmgalerie 451, 2009.- Bildtonträger.- 1 DVD Abschied : Brechts letzter Sommer / Josef Bierbichler, Monika Bleibtreu, Elfriede Irrall ... Buch: Klaus Pohl. Kamera: Edward KÚosiõski. Musik: John Cale. Regie: Jan Schütte München: Goethe-Institut e.V., 2013.- Bildtonträger.- 1 DVD (PAL, Ländercode-frei, 88 Min.) : farb., DD 2.0 Stereo Sprache: dt. - Untertitel: dt., engl., span., franz., port.. - Spielfilm. Deutschland. 2000 Absolute Giganten / ein Film von Sebastian Schipper. [Darst.]: Frank Giering, Florian Lukas, Antoine Monot, Julia Hummer. Kamera: Frank Griebe. Musik: The Notwist. Drehbuch und Regie: Sebastian Schipper Notwist München: Goethe-Institut e.V., 2012.- Bildtonträger.- 1 DVD (PAL, Ländercode-frei, 81 Min.) : farb., DD 2.0 Sprache: dt. - Untertitel: dt., span., port., engl., franz., ital., indo.. - Spielfilm. Deutschland. 1999 Absurdistan / ein Film von Veit Helmer. Mit: Maximilian Mauff, Kristýna MaléÂová und Schauspielern aus 18 Ländern. -

2018 Ich War Noch Niemals in New York (Service Production) Directed by Philipp Stölzl UFA Fiction Gmbh with Heike Makatsch, Moritz Bleibtreu, Katharina Thalbach And

COMPANY PROFILE - MMC MOVIES COLOGNE MMC Movies Köln GmbH co-produces and co-finances national and international feature films for cinema and TV. As co-producer, we participate in, and contribute financially to, film projects. If required, we can also assume the executive production in Cologne, Germany and Europe, bearing full financial responsibility—from pre-production to filming and post-production, up to execution. As co-production partner and film financer, we make substantial contributions to your production, while offering you a wide range of financing options. These include private equity, regional, national and European funding, Gap-financing and pre-sales. Thanks to our location in North Rhine-Westphalia, we also benefit from the support of the Film Foundation North Rhine-Westphalia—the Film- und Medienstiftung NRW—one of Germany’s largest regional film grant programs. On this basis, and together with you, we will draw up plans for a reliable and efficient financing structure for your project. Numerous national and international film productions have already benefited from MMC Movies’ superior location and the many years of experience in the financing and realization of film projects. Parallel to the production activity, MMC Movies also provides services for film productions. Our production services include leasing of soundstages and production offices, as well as set construction, among others. FILMOGRAPHY MMC MOVIES COLOGNE (May 2018) 2018 Ich war noch niemals in New York (Service Production) directed by Philipp Stölzl UFA