INTERPOLATIONS in the MAHABHARATA* By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

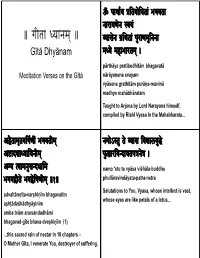

Microsoft Powerpoint

ॐ पाथाय ितबाधताे भगवता नारायणने वय ꠱ गीतॎ यॎनम् ꠱ यासेन थता पराणमिननापराणमु ुिनना Gītā Dhyānam मये महाभारतम् ꠰ pārthāya pratibodhitām bhagavatā Meditation Verses on the Gītā nārāyaṇena svayam vyāsena grathitām purāṇa-muninā madhyemahābhāratam Taught to Arjuna by Lord Narayana himself, compiled by Rishi Vyasa in the Mahabharata... अैतामतवषृ णी भगवतीम् नमाऽते त े यास वशालबु े अादशायाीयनीम् फु ारवदायतपन꠰ेे अब वामनसदधामवामनसदधामु namo 'stu te vyāsa viśhāla-buddhe phullāravindāyata-patra-netra भगवत े भवभवषणीमेषणीम् ꠱१꠱ Salutations to You, Vyyasa, whose intellect is vast, advaitāmṛita-varṣhiṇīm bhagavatīm whose eyes are like petals of a lotus... aṣhṭādaśhādhyāyinīm amba tvām anusandadhāmi bhagavad-gīte bhava-dveṣhiṇīm (1) ...this sacred rain of nectar in 18 chapters – O Mother Gita, I venerate You, destroyer of suffering. येन वया भारततलपै ूण पपारजाताय तावे े कपाणयै े꠰ वालता ेे ानमय दप ꠱२꠱ ानमु य कृ णाय गीतामृतदहु ेे नम ꠱३꠱ yena tvayā bhārata-taila-pūrṇaḥ prapanna-pārijātāya prajvālito jñāna-mayaḥ pradīpaḥ (2) totra-vetraika-pāṇaye jñāna-mudrāya kṛiṣhṇāya ...by whom the lamp filled with the oil of the gītāmṛita-dhduhenamaḥ (3) Mahabharata was lit with the flame of knowledge. Salutations to Krishna , who blesses the surrendered, in whose hands are a staff and the symbol of knowledge, who milks the Gita's nectar. सवापिनषदाे े गावा े दाधाे गापालनदने ꠰ वसदेवसत देव क सचाणरमदू नम꠰् पाथा े वस सध ीभााेे दधु गीतामृत महत् ꠰꠰ देेवकपरमानद कृ ण वदेे जगु म् ꠱꠱ sarvopaniṣhado gāvo vasudeva-sutam devam dogdhā gopāla-nandanaḥ kaḿsa-cāṇūra-mardanam pārtho vatsaḥ sudhīr bhoktā devakī-paramānandam ddhdugdham gītāmṛitam mahthat (4) kṛiṣhṇam vande jdjagad-gurum (5) The Upanishads are cows, Krishna is the cowherd, I revere Sri Krishna, teacher of all, son of Vasudeva, Arjuna is the calf, and wise people enjoy the sacred destroyer of Kamsa and Chanura, who is the delight nectar milked from the Gita. -

An Introduction to Sanskrit Chanda

[VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 3 I JULY – SEPT 2018] e ISSN 2348 –1269, Print ISSN 2349-5138 http://ijrar.com/ Cosmos Impact Factor 4.236 An Introduction to Sanskrit Chanda MITHUN HOWLADAR Ph. D Scholar, Department of Sanskrit, Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University, Purulia, West Bengal Received: May 22, 2018 Accepted: July 11, 2018 ABSTRACT We can generally say, any composition which has a musical sound, is called chanda. Chanda has been one of the Vedāṅgas since Vedic period. Vedic verses are composed in several chandas. The number of Vedic chandas is 21, out of which 7 are mainly used. Earliest poetic composition in public language (laukika Sanskrit) started from Valmiki, later it became a fashion and then a discipline for composition (kāvya). But here has been a difference in Vedic and laukika chandas. Where Vedic chnadas are identified by the number of syllables (varṇa or akṣara) in a line of verse or whole verse and the number of lines in the verse, laukika chanda is identified by the order of the laghu-guru syllables. The number of the laukika chandas is not yet finally defined but many texts have been composed describing the different number of chandas. Each chanda of laukika Sanskrit (post Vedic Sanskrit) consists of four pādas or caraṇas, that is, the fourth part of the chanda. Keywords: Chanda, Vedāṅgas, Chandaśāstra, pāda, Chandomañjarī. Introduction: Veda, the oldest literature in the world, is also called Chandas because the Vedic mantras (compositions) are all metric compositions (Chandobaddha). All the four Saṁhitās (with some exceptions in Yajurveda and Atharvaveda) are of this nature. -

Download (6MB)

Arya, Anwesha (2012) Dowry in tradition and text: śāstra, statute and the 'living law' of dowry as sadācāra in India. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/16639 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Dowry in tradition and text: Śāstra, statute and the ‘living law’ of dowry as sadācāra in India By Anwesha Arya PhD submission Department of the Study of Religions School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London September 23rd 2012 1 Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA PARVA translated by Kesari Mohan Ganguli In parentheses Publications Sanskrit Series Cambridge, Ontario 2002 Salya Parva Section I Om! Having bowed down unto Narayana and Nara, the most exalted of male beings, and the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. Janamejaya said, “After Karna had thus been slain in battle by Savyasachin, what did the small (unslaughtered) remnant of the Kauravas do, O regenerate one? Beholding the army of the Pandavas swelling with might and energy, what behaviour did the Kuru prince Suyodhana adopt towards the Pandavas, thinking it suitable to the hour? I desire to hear all this. Tell me, O foremost of regenerate ones, I am never satiated with listening to the grand feats of my ancestors.” Vaisampayana said, “After the fall of Karna, O king, Dhritarashtra’s son Suyodhana was plunged deep into an ocean of grief and saw despair on every side. Indulging in incessant lamentations, saying, ‘Alas, oh Karna! Alas, oh Karna!’ he proceeded with great difficulty to his camp, accompanied by the unslaughtered remnant of the kings on his side. Thinking of the slaughter of the Suta’s son, he could not obtain peace of mind, though comforted by those kings with excellent reasons inculcated by the scriptures. Regarding destiny and necessity to be all- powerful, the Kuru king firmly resolved on battle. Having duly made Salya the generalissimo of his forces, that bull among kings, O monarch, proceeded for battle, accompanied by that unslaughtered remnant of his forces. Then, O chief of Bharata’s race, a terrible battle took place between the troops of the Kurus and those of the Pandavas, resembling that between the gods and the Asuras. -

Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 11: 11

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 11 : 11 November 2011 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. S. M. Ravichandran, Ph.D. G. Baskaran, Ph.D. L. Ramamoorthy, Ph.D. Women in Mahabharata: Fighting Patriarchy Maneeta Kahlon, Ph.D. ======================================================== Vyasa’s Portrayal of Women Vyasa casts his women—Kunti, Draupadi, Gandhari, Shakuntala, Devayani, Savitri, Damayanti— both in the heroic mould and as victims and practitioners of elements of patriarchy The image of women in the original stratum of the epic is that which is etched out in the words of Shakuntala, as she upbraids Dushyanta for fickleness, contesting patriarchy and traditions of gender relations. ―A wife is a man‘s half, A wife is a man‘s closest friend; A wife is Dharma, Artha and Karna, A wife is Moksha too . A sweet-speaking wife is a companion in happy times; A wife is like a father on religious occasions; A wife is like a mother in illness and sorrow. The wife is a means to man‘s salvation . Happiness, joy, virtue, everything depends on her.‖ Citation Study of Male Authority and Subordination This paper is a study of the three central characters of Mahabharata and how they deal with male authority and subordination. The characters of Kunti, Gandhari, Draupadi conform to the elements of Stridharma while also manifesting exigent actions. Language in India www.languageinindia.com 11 : 11 November 2011 Maneeta Kahlon, Ph.D. -

Bhagavata Purana

Bhagavata Purana The Bh āgavata Pur āṇa (Devanagari : भागवतपुराण ; also Śrīmad Bh āgavata Mah ā Pur āṇa, Śrīmad Bh āgavatam or Bh āgavata ) is one of Hinduism 's eighteen great Puranas (Mahapuranas , great histories).[1][2] Composed in Sanskrit and available in almost all Indian languages,[3] it promotes bhakti (devotion) to Krishna [4][5][6] integrating themes from the Advaita (monism) philosophy of Adi Shankara .[5][7][8] The Bhagavata Purana , like other puranas, discusses a wide range of topics including cosmology, genealogy, geography, mythology, legend, music, dance, yoga and culture.[5][9] As it begins, the forces of evil have won a war between the benevolent devas (deities) and evil asuras (demons) and now rule the universe. Truth re-emerges as Krishna, (called " Hari " and " Vasudeva " in the text) – first makes peace with the demons, understands them and then creatively defeats them, bringing back hope, justice, freedom and good – a cyclic theme that appears in many legends.[10] The Bhagavata Purana is a revered text in Vaishnavism , a Hindu tradition that reveres Vishnu.[11] The text presents a form of religion ( dharma ) that competes with that of the Vedas , wherein bhakti ultimately leads to self-knowledge, liberation ( moksha ) and bliss.[12] However the Bhagavata Purana asserts that the inner nature and outer form of Krishna is identical to the Vedas and that this is what rescues the world from the forces of evil.[13] An oft-quoted verse is used by some Krishna sects to assert that the text itself is Krishna in literary -

Vidura, Uddhava and Maitreya

Çré Çayana Ekädaçé Issue no: 17 27th July 2015 Vidura, Uddhava and Maitreya Features VIDURA QUESTIONS UDDHAVA Srila Sukadeva Goswami THE MOST EXALTED PERSONALITY IN THE VRISHNI DYNASTY Lord Krishna instructing Uddhava Lord Sriman Purnaprajna Dasa UDDHAVA REMEMBERS KRISHNA Srila Vishvanatha Chakravarti Thakur UDDHAVA GUIDES VIDURA TO TAKE SHELTER OF MAITREYA ÅñI Srila Sukadeva Goswami WHY DID UDDHAVA REFUSE TO BECOME THE SPIRITUAL MASTER OF VIDURA? His Divine Grace A .C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada WHY DID KRISHNA SEND UDDHAVA TO BADRIKASHRAMA? Srila Vishvanatha Chakravarti Thakur WHO IS MAITREYA ÅñI? Srila Krishna-Dvaipayana Vyasa Issue no 16, Page — 2 nityaà bhägavata-sevayä VIDURA QUESTIONS UDDHAVA be the cause of the Åg Veda, the creator of the mind Srila Sukadeva Goswami and the fourth Plenary expansion of Viñëu. O sober one, others, such as Hridika, Charudeshna, Gada and After passing through very wealthy provinces like the son of Satyabhama, who accept Lord Sri Krishna Surat, Sauvira and Matsya and through western India, as the soul of the self and thus follow His path without known as Kurujangala. At last he reached the bank of deviation-are they well? Also let me inquire whether the Yamuna, where he happened to meet Uddhava, Maharaja Yudhisthira is now maintaining the kingdom the great devotee of Lord Krishna. Then, due to his great according to religious principles and with respect love and feeling, Vidura embraced him [Uddhava], for the path of religion. Formerly Duryodhana was who was a constant companion of Lord Krishna and burning with envy because Yudhisthira was being formerly a great student of Brihaspati's. -

Mahabharata Tatparnirnaya

Mahabharatha Tatparya Nirnaya Chapter XIX The episodes of Lakshagriha, Bhimasena's marriage with Hidimba, Killing Bakasura, Draupadi svayamwara, Pandavas settling down in Indraprastha are described in this chapter. The details of these episodes are well-known. Therefore the special points of religious and moral conduct highlights in Tatparya Nirnaya and its commentaries will be briefly stated here. Kanika's wrong advice to Duryodhana This chapter starts with instructions of Kanika an expert in the evil policies of politics to Duryodhana. This Kanika was also known as Kalinga. Probably he hailed from Kalinga region. He was a person if Bharadvaja gotra and an adviser to Shatrujna the king of Sauvira. He told Duryodhana that when the close relatives like brothers, parents, teachers, and friends are our enemies, we should talk sweet outwardly and plan for destroying them. Heretics, robbers, theives and poor persons should be employed to kill them by poison. Outwardly we should pretend to be religiously.Rituals, sacrifices etc should be performed. Taking people into confidence by these means we should hit our enemy when the time is ripe. In this way Kanika secretly advised Duryodhana to plan against Pandavas. Duryodhana approached his father Dhritarashtra and appealed to him to send out Pandavas to some other place. Initially Dhritarashtra said Pandavas are also my sons, they are well behaved, brave, they will add to the wealth and the reputation of our kingdom, and therefore, it is not proper to send them out. However, Duryodhana insisted that they should be sent out. He said he has mastered one hundred and thirty powerful hymns that will protect him from the enemies. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

The Upanishads Page

TThhee UUppaanniisshhaaddss Table of Content The Upanishads Page 1. Katha Upanishad 3 2. Isa Upanishad 20 3 Kena Upanishad 23 4. Mundaka Upanishad 28 5. Svetasvatara Upanishad 39 6. Prasna Upanishad 56 7. Mandukya Upanishad 67 8. Aitareya Upanishad 99 9. Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 105 10. Taittiriya Upanishad 203 11. Chhandogya Upanishad 218 Source: "The Upanishads - A New Translation" by Swami Nikhilananda in four volumes 2 Invocation Om. May Brahman protect us both! May Brahman bestow upon us both the fruit of Knowledge! May we both obtain the energy to acquire Knowledge! May what we both study reveal the Truth! May we cherish no ill feeling toward each other! Om. Peace! Peace! Peace! Katha Upanishad Part One Chapter I 1 Vajasravasa, desiring rewards, performed the Visvajit sacrifice, in which he gave away all his property. He had a son named Nachiketa. 2—3 When the gifts were being distributed, faith entered into the heart of Nachiketa, who was still a boy. He said to himself: Joyless, surely, are the worlds to which he goes who gives away cows no longer able to drink, to eat, to give milk, or to calve. 4 He said to his father: Father! To whom will you give me? He said this a second and a third time. Then his father replied: Unto death I will give you. 5 Among many I am the first; or among many I am the middlemost. But certainly I am never the last. What purpose of the King of Death will my father serve today by thus giving me away to him? 6 Nachiketa said: Look back and see how it was with those who came before us and observe how it is with those who are now with us. -

Introductiontotheniruktaandthelit

I n t ro du c t i o n t o t he N i r u kt a . a n d t h e L i te r at u r e re l at e d t o i t WTH TR T S E I A E A I O N The : E lement s o f the I ndi an A ccent RUDOLP H ROTH n Tr a s a t ed b the Rev CKI n . D . M A CHA N l y , D . D . , L L D P r i n ci a Wi s n Co e e o a B b s o me p l, l o ll g , m y, ' ‘ t i me Vi ce- Cha n cello r of the Umvemi i y of Pub l i s he d b y the Un i v ers ity o f Bo mb ay I 9 1 9 PRE FATORY N OTE . ’ FO R m any ye ars Yas k a s Nirukta has been regul arly prescribed by the University o f Bomb ay as a text fo a a a f r o . book r its ex min tion in S nskrit the degree of M A . ’ I n order t o render Roth s v alua ble Introduction to this w ork accessible to advanced students of S anskrit in Wil son College I prep ared long ago a transl ation of th is Intro duction which in m anuscript form did service to a succession O f College students some o f whom h ave since become w ell known a s S anskrit scholars .