Paper Opinions on Objects That Matter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Policy in the Polder

Cultural Policy in the Polder Cultural Policy in the Polder 25 years of the Dutch Cultural Policy Act Edwin van Meerkerk and Quirijn Lennert van den Hoogen (eds.) Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Koopman & Bolink: Boothuis, Noordoostpolder. Fotografie: Dirk de Zee. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 625 1 e-isbn 978 90 4853 747 1 doi 10.5117/9789462986251 nur 754 | 757 © The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2018 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. Table of Contents Acknowledgements 9 An Introduction to Cultural Policy in the Polder 11 Edwin van Meerkerk and Quirijn Lennert van den Hoogen A Well-Balanced Cultural Policy 37 An Interview with Minister of Culture Ingrid van Engelshoven Marielle Hendriks 1. Legal Aspects of Cultural Policy 41 Inge van der Vlies 2. An International Perspective on Dutch Cultural Policy 67 Toine Minnaert ‘A Subsidy to Make a Significant Step Upwards’ 85 An Interview with Arjo Klingens André Nuchelmans 3. The Framing Game 89 Towards Deprovincialising Dutch Cultural Policy Johan Kolsteeg1 4. Values in Cultural Policymaking 107 Political Values and Policy Advice Quirijn Lennert van den Hoogen and Florine Jonker An Exercise in Undogmatic Thinking 131 An Interview with Gable Roelofsen Bjorn Schrijen 5. -

7. Komitee Zuidelijk Afrika

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Aan de goede kant: Een geschiedenis van de Nederlandse anti- apartheidsbeweging 1960-1990 Muskens, R.W.A. Publication date 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Muskens, R. W. A. (2013). Aan de goede kant: Een geschiedenis van de Nederlandse anti- apartheidsbeweging 1960-1990. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:01 Oct 2021 7. Komitee Zuidelijk Afrika Inleiding In april 1959 richtten Sietse Bosgra en To van Albada Actie Informatie Algerije (AIA) op.1090 De aanleiding was hun ontzetting over de wandaden van de Fransen in hun Noord-Afrikaanse gebiedsdeel. Bosgra en de zijnen pakten de zaken voortvarend aan. Naast picket lines bij de Franse ambassade hield de Actie Informatie Algerije zich bezig met het vertalen van boeken en het schrijven van brochures over de anti-koloniale strijd in Algerije. -

Mass Murder in Perspective a Comparison of Influences on the Dutch Policy During the Genocides in Cambodia and Bosnia

Mass Murder in Perspective A Comparison of Influences on the Dutch Policy during the Genocides in Cambodia and Bosnia Author: Judith Scholte Student number: 5612497 E-mail: [email protected] Phone number: +31 6 23 50 81 90 Date: 06-08-2017 Words: 16,773 MA International Relations in Historical Perspective Supervisor: Prof. dr. Bob de Graaff Table of Contents Abstract ………..................................................................................................................... 3 List of Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………………………................ 4 1. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 2. Historical Context ……………………………………………….……………………………………………………. 10 o Historical OvervieW Cambodia …………………………..……………………………………………….. 10 o Ideas and Structure of the Early Khmer Rouge……………………………………………………. 10 o Lon Nol Regime ………………………………………………………….………………………………………. 11 o Khmer Rouge Coup ….…………………………………………………………………………………………. 12 o Historical OvervieW Yugoslavia, Bosnia and Srebrenica ……………………………………… 14 o Bosnia Enters the War ………………………………………………………………………………………… 15 o Comparison ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 18 3. Nature of the Genocide ……………………………….…………………………………………………………… 19 o Historical OvervieW Human Rights and Genocide ……………………………….……………… 19 o Cambodia …………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 20 o Bosnia and Srebrenica ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 23 o Comparison ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 24 4. Information Level and Government ….……………………………………………………………………... 26 o Historical OvervieW Dutch -

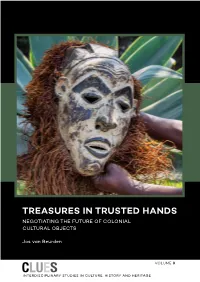

Treasures in Trusted Hands

Van Beurden Van TREASURES IN TRUSTED HANDS This pioneering study charts the one-way traffic of cultural “A monumental work of and historical objects during five centuries of European high quality.” colonialism. It presents abundant examples of disappeared Dr. Guido Gryseels colonial objects and systematises these into war booty, (Director-General of the Royal confiscations by missionaries and contestable acquisitions Museum for Central Africa in by private persons and other categories. Former colonies Tervuren) consider this as a historical injustice that has not been undone. Former colonial powers have kept most of the objects in their custody. In the 1970s the Netherlands and Belgium “This is a very com- HANDS TRUSTED IN TREASURES returned objects to their former colonies Indonesia and mendable treatise which DR Congo; but their number was considerably smaller than has painstakingly and what had been asked for. Nigeria’s requests for the return of with detachment ex- plored the emotive issue some Benin objects, confiscated by British soldiers in 1897, of the return of cultural are rejected. objects removed in colo- nial times to the me- As there is no consensus on how to deal with colonial objects, tropolis. He has looked disputes about other categories of contestable objects are at the issues from every analysed. For Nazi-looted art-works, the 1998 Washington continent with clarity Conference Principles have been widely accepted. Although and perspicuity.” non-binding, they promote fair and just solutions and help people to reclaim art works that they lost involuntarily. Prof. Folarin Shyllon (University of Ibadan) To promote solutions for colonial objects, Principles for Dealing with Colonial Cultural and Historical Objects are presented, based on the 1998 Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art. -

Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2011 Waar Visie Ontbreekt, Komt

Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2011 Waar visie ontbreekt, komt het volk om Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2011 Waar visie ontbreekt, komt het volk om Redactie: Carla van Baalen Hans Goslinga Alexander van Kessel Johan van Merriënboer Jan Ramakers Jouke Turpijn Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Boom – Amsterdam Foto omslag: Paul Babeliowsky / Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Vormgeving: Boekhorst Design B.V., Culemborg © 2011 Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Behoudens de in of krachtens de Auteurswet van 1912 gestelde uitzonderingen mag niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch door fotokopieën, opnamen of enig andere manier, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestem- ming van de uitgever. No part of this book may be reproduced in any way whatsoever without the written permission of the publisher. isbn 978 94 6105 546 0 nur 680 www.uitgeverijboom.nl Inhoud Ten geleide 9 Artikelen Henri Beunders, De terugkeer van de klassenstrijd. De angst van de visieloze burgerij 15 voor ‘de massa’ lijkt op die van rond 1900 Patrick van Schie, Ferm tegenspel aan ‘flauwekul’. De liberale politiek-filosofische 29 inbreng in het Nederlandse parlement: voor individuele vrijheid en evenwichtige volksinvloed Arie Oostlander, Aan Verhaal geen gebrek. Over de noodzaak van een betrouwbaar 41 kompas voor het cda Paul Kalma, Het sociaaldemocratisch program… en hoe het in de verdrukking kwam 53 Erie Tanja, ‘Dragers van beginselen.’ De parlementaire entree van Abraham Kuyper en 67 Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis Koen Vossen, Een Nieuw Groot Verhaal? Over de ideologie van lpf en pvv 77 Hans Goslinga en Marcel ten Hooven, ‘De vraag is of de democratie blijvend is.’ Interview 89 met J.L. -

Den Uyl, Lay-Out

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Joop den Uyl 1919-1987 : dromer en doordouwer Bleich, A. Publication date 2008 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Bleich, A. (2008). Joop den Uyl 1919-1987 : dromer en doordouwer. Uitgeverij Balans. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:23 Sep 2021 Den Uyl-revisie 18-01-2008 10:08 Pagina 481 noten Noten inleiding 1 H.D.TjeenkWillink,‘SpeechbijopenstellingvanhetarchiefvanDr.J.M.denUyl’op zaterdag1mei1993,iisg,Amsterdam,inprivéarchiefHermanTjeenkWillink. 2AnetBleich,Een partij in de tijd. Veertig jaar Partij van de Arbeid 1946-1986,Amster- dam,DeArbeiderspers,1986,p.157. 3 Willem Otterspeer,‘Een mozaïek van wrakhout. Een biograaf moet meer schrijver dan historicus willen zijn’,in Bespottelijk maar aangenaam.De biografie in Nederland,Ar- jenFortuinenJokeLinders(red.),Amsterdam,BasLubberhuizen,2007,p.98. -

De Lat Te Hoog

De lat te hoog Waarom er ondanks de stembusakkoorden van begin jaren zeventig uiteindelijk toch geen duidelijkheid voor de verkiezingen kwam Jan Erik Keman Studentnummer: 1194135 Master political culture and national identities Universiteit Leiden 2 De lat te hoog Waarom er ondanks de stembusakkoorden van begin jaren zeventig uiteindelijk toch geen duidelijkheid voor de verkiezingen kwam Inhoudsopgave Inleiding ............................................................................ 5 Hoofdstuk 1. De druppel ....................................................... 9 Hoofdstuk 2. Doorbraak poging nummer twee ........................ 14 Hoofdstuk 3. Een slechte generale ......................................... 23 Hoofdstuk 4. Hard tegen hard ............................................... 30 Hoofdstuk 5. Eindelijk duidelijkheid ..................................... 36 Hoofdstuk 6. Kleine partijen worden volwassen ...................... 44 Hoofdstuk 7. De apotheose: Keerpunt ‘72 ............................... 52 Hoofdstuk 8. Zwanenzang van het vooruitstrevende triumviraat 56 Conclusie. De lat te hoog ..................................................... 62 Dankwoord ........................................................................ 66 Lijst met afkortingen...........................................................67 Bronnen: ........................................................................................... Tijdschriften: ..................................................................................... Literatuurlijst -

Vloedgolf of Stroomversnelling? Protest

Vloedgolf of stroomversnelling? Protest tegen de afsluiting van de Oosterschelde tussen 1958 (aannemen van de Deltawet) en 1970 (de oprichting van de Aktiegroep Oosterschelde Open) Student: Suzanne de Lijser Studentnummer: s3046419 Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen Studie: Master Actuele Geschiedenis Begeleider: dr. W.P. van Meurs Datum: 15 april 2016 Inhoud Inleiding 3 Hoofdstuk 1: Breed protest tegen een gesloten Oosterschelde, 1970-1974 7 1.1 De Aktiegroep Oosterschelde Open: het stereotype beeld van protesterende 7 jongeren, ludieke acties en veel media-aandacht in de jaren zeventig 1.2 De tijdgeest van de jaren zeventig: verlangen naar hervorming en aandacht 9 voor het milieu Hoofdstuk 2: De politieke omslag in het Oosterschelde-beleid 13 2.1 De Oosterschelde in het kabinet-Den Uyl 13 2.2 Het Kamerdebat: ‘de ouwe eerlijke dam’ of een ‘geavanceerd experiment’? 14 2.3 Oorzaken van de omslag in het Oosterschelde-beleid 16 Hoofdstuk 3: Vroeg protest tegen de afsluiting, 1953-1970 18 3.1 Actie van de visserij. ‘Geef ons geen Oosterschelde dam, ’t Gaat om des 19 vissers boterham!’ 3.2 De kritiek van wetenschappers: de Oosterschelde als ‘zinkput van Europa’ 23 3.3 Een teleurstellend Oosterschelde-congres 26 3.4 De Studiegroep Oosterschelde: overleg in plaats van ‘toestanden met stickers’ 28 3.5 De media over de Oosterschelde-kwestie 30 Hoofdstuk 4: De Oosterschelde-kwestie in de politiek, 1953-1970 32 4.1 Het Deltaplan in de Tweede Kamer: ‘offers’ voor bescherming tegen 32 de ‘erfvijand’ 4.2 Reacties van de politiek op het toenemend protest 33 4.3 Rijkswaterstaat: van aanzien en macht naar rumoer en kritiek 35 4.4 De tijdgeest van de jaren vijftig en zestig: ‘Stilte voor de storm, 37 maar niet windstil’ Conclusie: geen vloedgolf, maar stroomversnelling in de jaren zeventig 40 Literatuur 43 2 Inleiding In de nacht van 31 januari op 1 februari 1953 voltrok zich in Zuidwest-Nederland een ramp, waarbij met name de provincie Zeeland zwaar werd getroffen. -

“Experiencing a Living Past” Trends in Dutch Castle Museum Practices and the Influence of National Cultural Policy

“Experiencing a Living Past” Trends in Dutch castle museum practices and the influence of national cultural policy Emma Storm 6303498 MA Thesis Cultural History of Modern Europe Utrecht University 29-08-2019 Abstract This thesis investigates the recent trend in heritage in which the visitor experience has become central. Previously conservation and preservation were the main objectives in the management of Dutch castle museums, while visitor oriented approaches were viewed with skepticism and reserve. This is different from the situation today where many castle museums promise the visitor a true experience through a variety of presentations and events. The question why Dutch castle museums have adopted a new approach in which experience is central, is the main research question of this thesis. In order to answer this question this thesis will explore how different elements like government policy and changing discourses influence heritage trends and presentations. By researching the cultural policy of the Dutch government and placing this next to developments in the heritage sector, the influence of cultural policy on this ‘experience’ trend will become clear. This thesis argues that the increase of neoliberalism in cultural policy has contributed to this ‘experience’ trend by making visitor numbers and revenue central to the value of heritage. 1 Preface I wrote this thesis as the final project of my masters programme Cultural History of Modern Europe at the University of Utrecht. I would like to thank a number of people for their support and advice during the writing process. My supervisor Gertjan Plets for his supportive feedback and encouragement. Norbert, Herma, my family and friends, who have helped me throughout the writing process with their endless support. -

Part II Colonialism and Cultural Objects………………………………………………………38 Chapter 3 Colonial Expansion……………………………………………………………………………………39 3.1

VU Research Portal Treasures in Trusted Hand Negotiating the future of colonial cultural objects van Beurden, J.M. 2016 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) van Beurden, J. M. (2016). Treasures in Trusted Hand Negotiating the future of colonial cultural objects. https://www.sidestone.com/books/?q=beurden General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Treasures in Trusted Hands - Full manuscript - September 2016 - ©Jos van Beurden VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT Treasures in Trusted Hand Negotiating the future of colonial cultural objects ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. V. Subramaniam, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van de promotiecommissie van de Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen op woensdag 30 november 2016 om 9.45 uur in de aula van de universiteit, De Boelelaan 1105 door Joseph Maria van Beurden geboren te Rotterdam 1 Treasures in Trusted Hands - Full manuscript - September 2016 - ©Jos van Beurden promoteren: prof. -

Advocacy Beyond Identity: a Dutch Gay/Lesbian Organization's

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Advocacy Beyond Identity: A Dutch Gay/Lesbian Organization’s Embrace of a Public Policy Strategy Davidson, R.J. DOI 10.1080/00918369.2018.1525944 Publication date 2020 Document Version Final published version Published in Journal of homosexuality License CC BY-NC-ND Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Davidson, R. J. (2020). Advocacy Beyond Identity: A Dutch Gay/Lesbian Organization’s Embrace of a Public Policy Strategy. Journal of homosexuality, 67(1), 35 – 57. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1525944 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 JOURNAL OF HOMOSEXUALITY 2020, VOL. 67, NO. 1, 35–57 https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1525944 Advocacy Beyond Identity: A Dutch Gay/Lesbian Organization’s Embrace of a Public Policy Strategy Robert J. -

Monumenten Van Beleid: De Wisselwerking Tussen Nederlands Rijksoverheidsbeleid, Sociale Wetenschappen En Politieke Cultuur, 1945-2002

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Monumenten van beleid: De wisselwerking tussen Nederlands rijksoverheidsbeleid, sociale wetenschappen en politieke cultuur, 1945-2002 Keulen, S.J. Publication date 2014 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Keulen, S. J. (2014). Monumenten van beleid: De wisselwerking tussen Nederlands rijksoverheidsbeleid, sociale wetenschappen en politieke cultuur, 1945-2002. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 Keulen Monumenten van Beleid van Monumenten De wisselwerking tussen Nederlands rijks overheidsbeleid, sociale wetenschappen onumenten van Beleid laat zien hoe topambtenaren, politici en sociale wetenschap- en politieke cultuur, 1945-2002 pers vanaf de wederopbouw tot de opkomst van Pim Fortuyn gezamenlijk het Mrijksoverheidsbeleid ontwikkelden. De grote veranderingen in de Nederlandse verzorgingsstaat worden aan de hand van ideaaltypes van beleid op het gebied van land- bouw, ontwikkelingssamenwerking, gevangenenzorg en milieubeleid geduid.