Woodcarving Traditions in Myanmar. Past and Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Bagan Period (1044 – 1113) Buddhism Is an Integral Part of Burmese Culture

Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Bagan Period (1044 – 1113) 2 Volumes By Charlotte Kendrick Galloway A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University November 2006 ii Declaration I declare that to the best of my knowledge, unless where cited, this thesis is my own original work. Signed: Date: Charlotte Kendrick Galloway iii Acknowledgments There are a number of people whose assistance, advice and general support, has enabled me to complete my research: Dr Alexandra Green, Dr Bob Hudson, Dr Pamela Gutman, Dick Richards, Dr Tilman Frasch, Sylvia Fraser- Lu, Dr Royce Wiles, Dr Don Stadtner, Dr Catherine Raymond, Prof Michael Greenhalgh, Ma Khin Mar Mar Kyi, U Aung Kyaing, Dr Than Tun, Sao Htun Hmat Win, U Sai Aung Tun and Dr Thant Thaw Kaung. I thank them all, whether for their direct assistance in matters relating to Burma, for their ability to inspire me, or for simply providing encouragement. I thank my colleagues, past and present, at the National Gallery of Australia and staff at ANU who have also provided support during my thesis candidature, in particular: Ben Divall, Carol Cains, Christine Dixon, Jane Kinsman, Mark Henshaw, Lyn Conybeare, Margaret Brown and Chaitanya Sambrani. I give special mention to U Thaw Kaung, whose personal generosity and encouragement of those of us worldwide who express a keen interest in the study of Burma's rich cultural history, has ensured that I was able to achieve my own personal goals. There is no doubt that without his assistance and interest in my work, my ability to undertake the research required would have been severely compromised – thank you. -

Myanmar Buddhism of the Pagan Period

MYANMAR BUDDHISM OF THE PAGAN PERIOD (AD 1000-1300) BY WIN THAN TUN (MA, Mandalay University) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the people who have contributed to the successful completion of this thesis. First of all, I wish to express my gratitude to the National University of Singapore which offered me a 3-year scholarship for this study. I wish to express my indebtedness to Professor Than Tun. Although I have never been his student, I was taught with his book on Old Myanmar (Khet-hoà: Mranmâ Râjawaà), and I learnt a lot from my discussions with him; and, therefore, I regard him as one of my teachers. I am also greatly indebted to my Sayas Dr. Myo Myint and Professor Han Tint, and friends U Ni Tut, U Yaw Han Tun and U Soe Kyaw Thu of Mandalay University for helping me with the sources I needed. I also owe my gratitude to U Win Maung (Tampavatî) (who let me use his collection of photos and negatives), U Zin Moe (who assisted me in making a raw map of Pagan), Bob Hudson (who provided me with some unpublished data on the monuments of Pagan), and David Kyle Latinis for his kind suggestions on writing my early chapters. I’m greatly indebted to Cho Cho (Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture, NUS) for providing me with some of the drawings: figures 2, 22, 25, 26 and 38. -

Merit-Making and Monuments: an Investigation Into the Role of Religious Monuments and Settlement Patterning Surrounding the Classical Capital of Bagan, Myanmar

MERIT-MAKING AND MONUMENTS: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE ROLE OF RELIGIOUS MONUMENTS AND SETTLEMENT PATTERNING SURROUNDING THE CLASSICAL CAPITAL OF BAGAN, MYANMAR A Thesis Submitted to the Committee on Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfill of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada ã Copyright by Ellie Tamura 2019 Anthropology M.A. Graduate Program January 2020 ABSTRACT Merit-Making and Monuments: An Investigation into the Role of Religious Monuments and Settlement Patterning Surrounding the Classical Capital of Bagan, Myanmar Ellie Tamura Bagan, Myanmar’s capital during the country’s Classical period (c. 800-1400 CE), and its surrounding landscape was once home to at least four thousand monuments. These monuments were the result of the Buddhist pursuit of merit-making, the idea that individuals could increase their socio-spiritual status by performing pious acts for the Sangha (Buddhist Order). Amongst the most meritous act was the construction of a religious monument. Using the iconographic record and historical literature, alongside entanglement theory, this thesis explores how the movement of labour, capital, and resources for the construction of these monuments influenced the settlement patterns of Bagan’s broader cityscape. The findings suggest that these monuments bound settlements, their inhabitants, and the Crown, in a variety of enabling and constraining relationships. This thesis has created the foundations for understanding the settlements of Bagan and serves as a useful platform to perform comparative studies once archaeological data for settlement patterning becomes available. Keywords: Southeast Asia, Settlement Patterns, Bagan, Entanglement, Religious Monuments, Buddhism, Archaeology ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For the past three years, I have been incredibly fortunate in having the opportunity to do what I love, in one of the most wonderful countries, none of which would have been possible without the support of an amazing group of people. -

Catazacke 20200425 Bd.Pdf

Provenances Museum Deaccessions The National Museum of the Philippines The Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University New York, USA The Monterey Museum of Art, USA The Abrons Arts Center, New York, USA Private Estate and Collection Provenances Justus Blank, Dutch East India Company Georg Weifert (1850-1937), Federal Bank of the Kingdom of Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia Sir William Roy Hodgson (1892-1958), Lieutenant Colonel, CMG, OBE Jerrold Schecter, The Wall Street Journal Anne Marie Wood (1931-2019), Warwickshire, United Kingdom Brian Lister (19262014), Widdington, United Kingdom Léonce Filatriau (*1875), France S. X. Constantinidi, London, United Kingdom James Henry Taylor, Royal Navy Sub-Lieutenant, HM Naval Base Tamar, Hong Kong Alexandre Iolas (19071987), Greece Anthony du Boulay, Honorary Adviser on Ceramics to the National Trust, United Kingdom, Chairman of the French Porcelain Society Robert Bob Mayer and Beatrice Buddy Cummings Mayer, The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Chicago Leslie Gifford Kilborn (18951972), The University of Hong Kong Traudi and Peter Plesch, United Kingdom Reinhold Hofstätter, Vienna, Austria Sir Thomas Jackson (1841-1915), 1st Baronet, United Kingdom Richard Nathanson (d. 2018), United Kingdom Dr. W. D. Franz (1915-2005), North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany Josette and Théo Schulmann, Paris, France Neil Cole, Toronto, Canada Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald (19021982) Arthur Huc (1854-1932), La Dépêche du Midi, Toulouse, France Dame Eva Turner (18921990), DBE Sir Jeremy Lever KCMG, University -

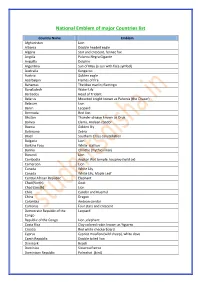

National Emblem of Major Countries List

National Emblem of major Countries list Country Name Emblem Afghanistan Lion Albania Double headed eagle Algeria Star and crescent, fennec fox Angola Palanca Negra Gigante Anguilla Dolphin Argentina Sun of May (a sun with face symbol) Australia Kangaroo Austria Golden eagle Azerbaijan Flames of fire Bahamas The blue marlin; flamingo Bangladesh Water Lily Barbados Head of Trident Belarus Mounted knight known as Pahonia (the Chaser) Belgium Lion Benin Leopard Bermuda Red lion Bhutan Thunder dragon known as Druk Bolivia Llama, Andean condor Bosnia Golden lily Botswana Zebra Brazil Southern Cross constellation Bulgaria Lion Burkina Faso White stallion Burma Chinthe (mythical lion) Burundi Lion Cambodia Angkor Wat temple, kouprey (wild ox) Cameroon Lion Canada White Lily Canada White Lily, Maple Leaf Central African Republic Elephant Chad(North) Goat Chad (South) Lion Chile Candor and Huemul China Dragon Colombia Andean condor Comoros Four stars and crescent Democratic Republic of the Leopard Congo Republic of the Congo Lion ,elephant Costa Rica Clay colored robin known as Yiguirro Croatia Red white checkerboard Cyprus Cypriot mouflon (wild sheep), white dove Czech Republic Double tailed lion Denmark Beach Dominica Sisserou Parrot Dominican Republic Palmchat (bird) Ecuador Andean condor Egypt Golden eagle Equatorial Guinea Silk cotton tree Eritrea Camel Estonia Barn swallow, cornflower Ethiopia Abyssinian lion European Union A circle of 12 stars Finland Lion France Lily Gabon Black panther Gambia Lion Georgia Saint George, lion Germany Corn -

Buddhist Art of Myanmar Press Release FINAL.Pdf

News Communications Department Asia Society 725 Park Avenue New York, NY 10021-5088 AsiaSociety.org Phone 212.327.9271 Contact: Elaine Merguerian 212.327.9313; [email protected] E-mail [email protected] ASIA SOCIETY MUSEUM TO PRESENT FIRST EXHIBITION IN THE WEST FOCUSED ON LOANS FROM COLLECTIONS IN MYANMAR Buddhist Art of Myanmar on view in New York February 10 through May 10, 2015 Asia Society Museum presents a landmark exhibition of spectacular works of art from collections in Myanmar and the United States. Buddhist Art of Myanmar comprises approximately 70 works from the fifth through the early twentieth century and includes stone, bronze, and lacquered wood sculptures as well as textiles, paintings, and ritual implements. The majority of works in the exhibition on loan from Myanmar have never been seen in the West. On view in New York from February 10 through May 10, 2015, the exhibition showcases Buddhist objects created for temples, monasteries, and personal devotion, presented in their historical and ritual contexts. Exhibition artworks highlight the long and continuous presence of Buddhism in Myanmar since Plaque with image of seated Buddha. Pagan period, the first millennium, as well as the unique combination 11th -13th century . Gilded metal with polychrome. of style, technique, and religious deities that appeared 7 x 6.14 x 0.25 in . (17.8 x15.9 x 0.6 cm). Bagan Archaeological Museum. Photo: Sean Dungan. in the arts of Buddhist Myanmar. Buddhist Art of Myanmar includes loans from the National Museums in Yangon and Nay Pyi T aw, the Bagan Archaeological Museum, Sri Ksetra Archaeological Museum, and the Kaba Aye Buddhist Art Museum, as well as works from public and private collections in the United States. -

Neil Sowards

NEIL SOWARDS c 1 LIFE IN BURMA © Neil Sowards 2009 548 Home Avenue Fort Wayne, IN 46807-1606 (260) 745-3658 Illustrations by Mehm Than Oo 2 NEIL SOWARDS Dedicated to the wonderful people of Burma who have suffered for so many years of exploitation and oppression from their own leaders. While the United Nations and the nations of the world have made progress in protecting people from aggressive neighbors, much remains to be done to protect people from their own leaders. 3 LIFE IN BURMA 4 NEIL SOWARDS Contents Foreword 1. First Day at the Bazaar ........................................................................................................................ 9 2. The Water Festival ............................................................................................................................. 12 3. The Union Day Flag .......................................................................................................................... 17 4. Tasty Tagyis ......................................................................................................................................... 21 5. Water Cress ......................................................................................................................................... 24 6. Demonetization .................................................................................................................................. 26 7. Thanakha ............................................................................................................................................ -

Journal of Urban History

Journal of Urban History http://juh.sagepub.com/ Urban Forms and Civic Space in Nineteenth- to Early Twentieth-Century Bangkok and Rangoon Elizabeth Howard Moore and Navanath Osiri Journal of Urban History 2014 40: 158 originally published online 27 September 2013 DOI: 10.1177/0096144213504381 The online version of this article can be found at: http://juh.sagepub.com/content/40/1/158 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: Urban History Association Additional services and information for Journal of Urban History can be found at: Email Alerts: http://juh.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://juh.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav >> Version of Record - Nov 26, 2013 OnlineFirst Version of Record - Sep 27, 2013 What is This? Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at SOAS London on December 1, 2013 JUH40110.1177/0096144213504381Journal of Urban HistoryHoward-Moore and Osiri 504381research-article2013 Article Journal of Urban History 2014, Vol 40(1) 158 –177 Urban Forms and Civic Space in © 2013 SAGE Publications Reprints and permissions: Nineteenth- to Early Twentieth- sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0096144213504381 Century Bangkok and Rangoon juh.sagepub.com Elizabeth Howard Moore1 and Navanath Osiri2 Abstract Buddhist spaces in Bangkok and Rangoon both had long common traditions prior to nineteenth- and early twentieth-century colonial incursions. Top–down central city planning with European designs transformed both cities. While Siamese kings personally initiated civic change that began to widen economic and social interaction of different classes, British models segregated European, Burmese, Indian, and Chinese populations to exacerbate social differences. -

Materiality and Construction of a Church in Myanmar

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Theses from the M. Arch. Program Architecture, College of Spring 5-3-2021 Materiality and Construction of a Church in Myanmar Sunkist Judson University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/marchthesis Part of the Architecture Commons Judson, Sunkist, "Materiality and Construction of a Church in Myanmar" (2021). Theses from the M. Arch. Program. 31. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/marchthesis/31 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Architecture, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses from the M. Arch. Program by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. University of Nebraska-Lincoln Materiality and Construction of a Church in Myanmar By: Sunkist Judson A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FUL- FILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Master of Architecture APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE: Sign and Date Dr. Sharon Kuska Materiality and Construction of a Church in Myanmar Sunkist Judson April 29th, 2021 ARCH 544 Thesis Spring 2021 01 02 Abstract This is my investigation related to Theinla village church. This is an investigation of architectural impacts on a protestant religious house of worship experience through a cultural case study. Churches were built and design based on worship culture and traditions. Churches have evolved for over two thousand years due to innovation and technology and imitating previous architecture styles. The way people worship in protestant religion is a little different in every culture. I would like to find out if there is any overlap in Baptist churches in different cultures. -

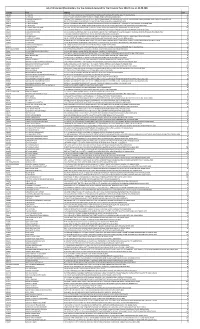

For the Dividend Declared for the Financial Year 2012-13 As on 12.09.2017

List of Unclaimed Shareholders: For the dividend declared for the Financial Year 2012-13 as on 12.09.2017 FOLIO NO NAME ADDRESS AMT A04314 A B FONTES 104 IVTH CROSS KALASIPALYAM NEW EXTENSION BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,PIN-560002,INDIA 25 A17671 A C SRAJAN 66 LUZ CHURCH ROAD MYLAPORE CHENNAI CHENNAI,TAMIL NADU,PIN-600004,INDIA 180 D00252 A DHAKSHINAMOORTHY PARTNER V M C TRADERS STOCKISTS OF A C LTD 6/10 MARIAMMAN KOIL RAMANATHAPURAM DT RAMANATHAPURAM RAMNAD,TAMIL NADU,PIN-623501,INDIA 90 A02076 A JANARDHAN 8/1101 SESHAGIRINIVAS NEW ROAD COCHIN COCHIN ERNAKULAM,KERALA,PIN-682002,INDIA 25 A02270 A K BHATTACHARYA UNITED COMMERCIAL BANK MATA ANANDA NAGAR SHIVALA HOSPITAL VARANASI U P VARANASI,UTTAR PRADESH,PIN-221001,INDIA 25 A03705 A K NARAYANA C/O A K KESAUACHAR 451 TENTH CROSS GIRINAGAR SECOND PHASE BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,PIN-560085,INDIA 25 P00351 A K RAMACHANDRAPRABHU 'PAVITRA' NO 949 24TH MAIN ROAD J P NAGAR II PHASE BANGALORE BANGALORE,KARNATAKA,PIN-560078,INDIA 360 A17411 A KALPAKAM NARAYAN C/O V KAMESWARARAO 7-6-108 ENUGULAMALAL STREET SRIKAKULAM (A.P.) SRIKAKULAM,ANDHRA PRADESH,PIN-532001,INDIA 18 A03555 A LAKSHMINARAYANA C/O G ARUNACHALAM RANA PLOT NO 30 LEPAKSHI COLONY WEST MARREDPALLY SECUNDERABAD HYDERABAD,ANDHRA PRADESH,PIN-500026,INDIA 25 A04366 A M DAVID 1 MISSION COMPOUND AJMER ROAD JAIPUR JAIPUR,RAJASTHAN,PIN-302006,INDIA 25 M00394 A MURUGESAN 3 A D BLOCK V G RAO NAGAR EXTENSION KATPADI P O VELLORE N A A DT VELLORE NORTH ARCOT,TAMIL NADU,PIN-632007,INDIA 23 A17672 A N VENKATALAKSHMI 361 XI A CROSS 29TH MAIN J -

Appendix Appendix

APPENDIX APPENDIX DYNASTIC LISTS, WITH GOVERNORS AND GOVERNORS-GENERAL Burma and Arakan: A. Rulers of Pagan before 1044 B. The Pagan dynasty, 1044-1287 C. Myinsaing and Pinya, 1298-1364 D. Sagaing, 1315-64 E. Ava, 1364-1555 F. The Toungoo dynasty, 1486-1752 G. The Alaungpaya or Konbaung dynasty, 1752- 1885 H. Mon rulers of Hanthawaddy (Pegu) I. Arakan Cambodia: A. Funan B. Chenla C. The Angkor monarchy D. The post-Angkor period Champa: A. Linyi B. Champa Indonesia and Malaya: A. Java, Pre-Muslim period B. Java, Muslim period C. Malacca D. Acheh (Achin) E. Governors-General of the Netherlands East Indies Tai Dynasties: A. Sukhot'ai B. Ayut'ia C. Bangkok D. Muong Swa E. Lang Chang F. Vien Chang (Vientiane) G. Luang Prabang 954 APPENDIX 955 Vietnam: A. The Hong-Bang, 2879-258 B.c. B. The Thuc, 257-208 B.C. C. The Trieu, 207-I I I B.C. D. The Earlier Li, A.D. 544-602 E. The Ngo, 939-54 F. The Dinh, 968-79 G. The Earlier Le, 980-I009 H. The Later Li, I009-I225 I. The Tran, 1225-I400 J. The Ho, I400-I407 K. The restored Tran, I407-I8 L. The Later Le, I4I8-I8o4 M. The Mac, I527-I677 N. The Trinh, I539-I787 0. The Tay-Son, I778-I8o2 P. The Nguyen Q. Governors and governors-general of French Indo China APPENDIX DYNASTIC LISTS BURMA AND ARAKAN A. RULERS OF PAGAN BEFORE IOH (According to the Burmese chronicles) dat~ of accusion 1. Pyusawti 167 2. Timinyi, son of I 242 3· Yimminpaik, son of 2 299 4· Paikthili, son of 3 . -

Buddhism, Power and Political Order

BUDDHISM, POWER AND POLITICAL ORDER Weber’s claim that Buddhism is an otherworldly religion is only partially true. Early sources indicate that the Buddha was sometimes diverted from supra- mundane interests to dwell on a variety of politically related matters. The significance of Asoka Maurya as a paradigm for later traditions of Buddhist kingship is also well attested. However, there has been little scholarly effort to integrate findings on the extent to which Buddhism interacted with the polit- ical order in the classical and modern states of Theravada Asia into a wider, comparative study. This volume brings together the brightest minds in the study of Buddhism in Southeast Asia. Their contributions create a more coherent account of the relations between Buddhism and political order in the late pre-modern and modern period by questioning the contested relationship between monastic and secular power. In doing so, they expand the very nature of what is known as the ‘Theravada’. This book offers new insights for scholars of Buddhism, and it will stimulate new debates. Ian Harris is Professor of Buddhist Studies at the University of Cumbria, Lancaster, and was Senior Scholar at the Becket Institute, St Hugh’s College, University of Oxford, from 2001 to 2004. He is co-founder of the UK Association for Buddhist Studies and has written widely on aspects of Buddhist ethics. His most recent book is Cambodian Buddhism: History and Practice (2005), and he is currently responsible for a research project on Buddhism and Cambodian Communism at the Documentation Center of Cambodia [DC-Cam], Phnom Penh. ROUTLEDGE CRITICAL STUDIES IN BUDDHISM General Editors: Charles S.