Piracy: the World's Third-Oldest Profession

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ocean in the Atlantic: British Experience and Imagination in an Imperial Sea, Ca

The Ocean in the Atlantic: British Experience and Imagination in an Imperial Sea, ca. 1600-1800 Heather Rose Weidner Chino Hills, California BA, Swarthmore College, 2000 MA, University of Virginia, 2002 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia May, 2014 i Table of Contents Abstract ii Acknowledgements iii Abbreviations vi Images vii 1. Introduction: Maritime, Anxious, Godly, and Sociable 1 2. Sing a Song of Shipwrecks 28 3. Between Wind and Water 95 4. Wrecked 166 5. To Aid Poor Sailors 238 6. Conclusion: God speed the barge 303 Appendix 1 315 Appendix 2 322 Bibliography 323 ii Abstract For Britons in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, “the Atlantic” was not a field of study -- it was an ocean. In this dissertation I argue for an environmentally minded Atlantic history, one that is conscious of the ocean as both a cultural and a physical presence. The ocean shaped an early modern Atlantic vernacular that was at its essence maritime, godly, anxious and sociable. The ocean was a conduit to empire, so anything Britons imagined about the oceans, they imagined about their empire as well. Britons could never fully master their empire because they could never master the ocean; it was source of anxiety for even the wealthiest merchants. The fear of extremity – of wreck and ruin – kept those who crossed the ocean focused on the three most valuable Atlantic commodities: a sound reputation, accurate information, and the mercy of God. -

Historical Memory and History in the Memoirs of Iraqi Jews*

Historical Memory and History in the Memoirs of Iraqi Jews* Mark R. Cohen Memoirs, History, and Historical Memory Following their departure en masse from their homeland in the middle years of the twentieth century, Jews from Iraq produced a small library of memoirs, in English, French, Hebrew, and Arabic. These works reveal much about the place of Arab Jews in that Muslim society, their role in public life, their relations with Muslims, their involvement in Arab culture, the crises that led to their departure from a country in which they had lived for centuries, and, finally, their life in the lands of their dispersion. The memoirs are complemented by some documentary films. The written sources have aroused the interest of historians and scholars of literature, though not much attention has been paid to them as artifacts of historical memory.1 That is the subject of the present essay. Jews in the Islamic World before the Twentieth Century Most would agree, despite vociferous demurrer in certain "neo-lachrymose" circles, that, especially compared to the bleaker history of Jews living in Christian lands, Jews lived fairly securely during the early, or classical, Islamic * In researching and writing this paper I benefited from conversations and correspondence with Professors Sasson Somekh, Orit Bashkin, and Lital Levy and with Mr. Ezra Zilkha. Though a historian of Jews in the Islamic world in the Middle Ages, I chose to write on a literary topic in honor of Tova Rosen, who has contributed so much to our knowledge of another branch of Jewish literature written by Arab Jews. -

Tot Shabbat in Strawberry Fields

TempleTemple TimesTimes Feb 2019 • Shevat/Adar 5779 Volume 306 • URJ Affiliated Temple Emanu-El Sarasota, Florida • Founded 1956 Judaism does not want us to despair in who are sick, but also of those who care for Rabbi’s Message illness, rather we are a people of hope. One them. act that manifests hope is our prayers. In our We also keep a silent healing list. Some sanctuary, when singing Mi Shebeirach, we of our members are more private. Some on are praying as a community. We are plead- the silent list are fighting long term battles. ing with God to bless and heal, to restore and We also pray for them. strengthen, and to make this happen swiftly. One of the greatest moments at temple is During many Shabbat services, we taking someone off the healing list when they faithfully offer one of the most beloved and are better. The return to services for the first familiar versions of Mi Shebeirach by Debbie time is cause for celebration and thanks. Friedman. When we sing this prayer, we ask We don’t always know that one of our the “Source of strength, who blessed the ones members is in the hospital or that someone before us, to help us find the courage to make you care for is ill. We want to know. Until the our lives a blessing” and to “bless those in day comes when all who are sick are healed, need of healing with r’fuah sh’leimah, the we ask you to please let us know when a renewal of body, the renewal of spirit.” name should be added to our healing lists. -

Pirate Utopias: Moorish Corsairs & European Renegadoes Author: Wilson, Peter Lamborn

1111111 Ullllilim mil 1IIII 111/ 1111 Sander, Steven TN: 117172 Lending Library: CLU Title: Pirate utopias: Moorish corsairs & European Renegadoes Author: Wilson, Peter Lamborn. Due Date: 05/06/11 Pieces: 1 PLEASE DO NOT REMOVE TIDS LABEL ILL Office Hours: Monday-Friday, 8am to 4:30pm Phone: 909-607-4591 h«p:llclaremontmiad.oclc.org/iDiadllogon.bbnl PII\ATE UTOPIAS MOORISH CORSAIRS & EUROPEAN I\ENEGADOES PETER LAMBOl\N WILSON AUTONOMEDIA PT o( W5,5 LiaoS ACK.NOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to thank the New York Public Library, which at some time somehow acquired a huge pirate-lit col lection; the Libertarian Book Club's Anarchist Forums, and T A8LE OF CONTENTS the New York Open Center. where early versions were audi ence-tested; the late Larry Law, for his little pamphlet on Captain Mission; Miss Twomey of the Cork Historical I PIl\ATE AND MEl\MAlD 7 Sociel;y Library. for Irish material; Jim Koehnline for art. as n A CHl\ISTIAN TUl\N'D TUl\K 11 always; Jim Fleming. ditto; Megan Raddant and Ben 27 Meyers. for their limitless capacity for toil; and the Wuson ill DEMOCI\.ACY BY ASSASSINATION Family Trust, thanks to which I am "independently poor" and ... IV A COMPANY OF l\OGUES 39 free to pursue such fancies. V AN ALABASTEl\ PALACE IN TUNISIA 51 DEDlCATION: VI THE MOOI\.ISH l\EPU8LlC OF SALE 71 For Bob Quinn & Gordon Campbell, Irish Atlanteans VII MUI\.AD l\EIS AND THE SACK OF BALTIMOl\E 93 ISBN 1-57027-158-5 VIII THE COI\.SAIl\'S CALENDAl\ 143 ¢ Anti-copyright 1995, 2003. -

Edizione Scaricabile

Mediterranea n. 34 (cop)_Copertina n. 34 21/07/15 19:19 Pagina 1 0Prime_1 06/08/15 18:51 Pagina 255 0Prime_1 06/08/15 18:51 Pagina 256 0Prime_1 06/08/15 18:51 Pagina 257 n° 34 Agosto 2015 Anno XII 0Prime_1 06/08/15 18:51 Pagina 258 Direttore: Orazio Cancila Responsabile: Antonino Giuffrida Comitato scientifico: Bülent Arı, Maurice Aymard, Franco Benigno, Henri Bresc, Rossella Cancila, Federico Cresti, Antonino De Francesco, Gérard Delille, Salvatore Fodale, Enrico Iachello, Olga Katsiardi-Hering, Salvatore Lupo, María Ángeles Pérez Samper, Guido Pescosolido, Paolo Preto, Luis Ribot Garcia, Mustafa Soykut, Marcello Verga, Bartolomé Yun Casalilla Segreteria di Redazione: Amelia Crisantino, Nicola Cusumano, Fabrizio D'Avenia, Matteo Di Figlia, Valentina Favarò, Daniele Palermo, Lavinia Pinzarrone Direzione, Redazione e Amministrazione: Cattedra di Storia Moderna Dipartimento Culture e Società Viale delle Scienze, ed. 12 - 90128 Palermo Tel. 091 23899308 [email protected] online sul sito www.mediterranearicerchestoriche.it Il presente numero a cura di Maria Pia Pedani è pubblicato con il contributo dell'Associazione di Studi Storici 'Muda di Levante' Mediterranea - ricerche storiche ISSN: 1824-3010 (stampa) ISSN: 1828-230X (online) Registrazione n. 37, 2/12/2003, della Cancelleria del Tribunale di Palermo Iscrizione n. 15707 del Registro degli Operatori di Comunicazione Copyright © Associazione no profit “Mediterranea” - Palermo I fascicoli a stampa di "Mediterranea - ricerche storiche" sono disponibili presso la NDF (www.newdigitalfrontiers.com), che ne cura la distribuzione: selezionare la voce "Mediterranea" nella sezione "Collaborazioni Editoriali". In formato digitale sono reperibili sul sito www.mediterranearicerchestoriche.it. I testi sono sottoposti a referaggio in doppio cieco. -

Jewish Pirates of the Her Deceased Husband If He Refuses to Marry Her

History REVIEWS American dictator, supported the project.) A JEWISH PIRATES throughout Jewish history. From early biblical bilingual (Spanish and English) exhibition OF THE CARIBBEAN: references, to the iconic sandal of the modern held at The Museum of Jewish Heritage in HOW A GENERATION Jewish kibbutzniks, we learn that the shoe is New York City accompanied the launching of OF SWASHBUCKLING indeed a reflection into the “soul” of the Jew. the book. JEWS CARVED OUT From biblical times, shoes have played an Marion A. Kaplan, author of Beyond Dig- AN EMPIRE IN THE integral role in the relationship of the chosen nity and Despair: Jewish Life in Nazi Germany, NEW WORLD IN people to their God. It is the command that organizes her history into seven well defined THEIR QUEST Moses remove his shoes that preceded God’s chapters in chronological order. The photo- FOR TREASURE, conveying his plan to deliver his people out of graphs of life on the farm emphasize the role RELIGIOUS FREEDOM—AND REVENGE slavery. The role of the shoe in Jewish tradition- of agriculture in the endeavor. Indeed it was Edward Kritzler al rituals is also examined in the course of sev- farming that was the driving force of the set- Doubleday, 2008. 324 pp. $26.00 eral articles. The halitzah ceremony invoked in tlement, giving Jews a new vocation that ISBN: 978-0-385-57398-2 the book of Deuteronomy requires that a child- enabled them to exist and even thrive in this less widow remove the shoe of the brother of haven. If the story of the Jews of Sosúa is a ith its alluring cover, Jewish Pirates of the her deceased husband if he refuses to marry her. -

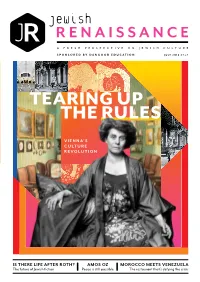

Tearing up the Rules

Jewish RENAISSANCE A FRESH PERSPECTIVE ON JEWISH CULTURE SPONSORED BY DANGOOR EDUCATION JULY 2018 £7.25 TEARING UP THE RULES VIENNA’S CULTURE REVOLUTION IS THERE LIFE AFTER ROTH? AMOS OZ MOROCCO MEETS VENEZUELA The future of Jewish fiction Peace is still possible The restaurant that’s defying the crisis JR Pass on your love of Jewish culture for future generations Make a legacy to Jewish Renaissance ADD A LEGACY TO JR TO YOUR WILL WITH THIS SIMPLE FORM WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK/CODICIL GO TO: WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK/DONATIONS FOR INFORMATION ON ALL WAYS TO SUPPORT JR CHARITY NUMBER 1152871 JULY 2018 CONTENTS WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK JR YOUR SAY… Reader’s rants, raves 4 and views on the April issue of JR. WHAT’S NEW We announce the 6 winner of JR’s new arts award; Mike Witcombe asks: is there life after Roth? FEATURE Amos Oz on Israel at 10 70, the future of peace, and Trump’s controversial embassy move. FEATURE An art installation in 12 French Alsace is breathing new life into an old synagogue. NATALIA BRAND NATALIA © PASSPORT Vienna: The writers, 14 artists, musicians and thinkers who shaped modernism. Plus: we speak to the contemporary arts activists working in Vienna today. MUSIC Composer Na’ama Zisser tells Danielle Goldstein about her 30 CONTENTS opera, Mamzer Bastard. ART A new show explores the 1938 32 exhibition that brought the art the Nazis had banned to London. FILM Masha Shpolberg meets 14 34 the director of a 1968 film, which followed a group of Polish exiles as they found haven on a boat in Copenhagen. -

Jewish Pirates

Jewish Pirates by Long John Silverman The Wikipedia page on piracy gives you a lot of clues, if you know what to look for. One of the biggest clues are these two sentences, conspicuously stuck right next to each other: The earliest documented instances of piracy are the exploits of the Sea Peoples who threatened the ships sailing in the Aegean and Mediterranean waters in the 14th century BC. In classical antiquity, the Phoenicians, Illyrians and Tyrrhenians were known as pirates. Wikipedia is all but admitting what our historians do gymnastics to avoid admitting: Sea Peoples = Phoenicians. Just as we suspected. We can ignore “Illyrians” and “Tyrrhenians,” which are just poorly devised synonyms for Phoenicians. Wiki tells us Tyrrhenian is simply what the Greeks called a non-Greek person, but then it states that Lydia was “the original home of the Tyrrhenians,” which belies the fact that they were known by the Greeks as a specific people from a specific place, not just any old non-Greek person. Wiki then cleverly tells us “Spard” or “Sard” was a name “closely connected” to the name Tyrrhenian, since the Tyrrhenian city of Lydia was called Sardis by the Greeks. (By the way, coins were first invented in Lydia – so they were some of the earliest banksters). But that itself is misleading, since the Lydians also called themselves Śfard. Nowhere is the obvious suggested – that Spard/Śfard looks a lot like Sephardi, as in Sephardi Jews. These refer to Jews from the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal), the word coming from Sepharad, a place mentioned in the book of Obadiah whose location is lost to history. -

Library Collection 20-08-23 Changes

Temple Sholom Library 8/24/2020 BOOK PUB CALL TITLE AUTHOR FORMAT CATEGORY KEYWORDS DATE NUMBER Foundation, The Blue #QuietingTheSilence: Personal Stories Dove Paperback Spiritual SelfHelp (Books) 246.7 BDF .The Lion Seeker Bonert, Kenneth Paperback Fiction 2013 F Bo 10 Things I Can Do to Help My World Walsh, Melanie Paperback Children's Diet & Nutrition Books (Books) mitzvah, tikkun olam J Wa Children's Books : Literature : Classics by Age 10 Traditional Jewish Children's Stories Goldreich, Gloria Hardcover : General Children's stories, Hebrew, Legends, Jewish 1996 J 185.6 Go 100+ Jewish Art Projects for Children Feldman, Margaret A. Paperback Religion Biblical Studies Bible. O.T. Pentateuch Textbooks 1984 1001 Yiddish Proverbs Kogos, Fred Paperback Language selfstudy & phrasebooks 101 Classic Jewish Jokes : Jewish Humor from Groucho Marx to Jerry Seinfeld Menchin, Robert Paperback Entertainment : Humor : General Jewish wit and humor 1998 550.7 101 Myths of the Bible Greenberg, Gary Hardcover Bible Commentaries 2000 .002 Gr 1918: War and Peace Dallas, Gregor Hardcover 20th Century World History World War, 19141918 Peace, World War, 19141918 Armistices IsraelArab War, 19481949Armistices, Palestinian ArabsGovernment policy 1949 the First Israelis Segev, Tom Paperback History of Judaism Israel, ImmigrantsIsraelSocial conditions, Orthodox JudaismRelationsIsrael 1967: Israel, the War, and the Year that Transformed the Middle East Segev, Tom Hardcover 20th Century World History IsraelArab War, 1967, IsraelPolitics and government20th century -

B-J News As I Considered This Editorial, Many Themes Came to Mind but None Seemed Right

FROM THE EDITOR B-J News As I considered this editorial, many themes came to mind but none seemed right. This is mostly because I’ve been out of The newsletter of the British Jewry mailing list the genealogical loop of late, trying to sell my house and ease th Saturday 16 December 2006/25 Kislev 5767 myself into retirement, as well as see my son married. Welcome to the ninth edition of B-J News I’m also helping to plan my 50 th high school reunion - and there’s my CONTENTS inspiration: I want to discuss universal networking. Three alumni, scattered in Arizona, Texas and California - not close together - are From The Editor page 1 planning the reunion in Chicago! We’ve found all the graduates - From the List page 2 including those missing since we had the first reunion. With the help of the Internet and e-mail, we’ve done just about everything, from finding a Ben or Bar page 4 hotel to tracking women whose married names were unknown; from Another Plea for the Preservation of Our Sources page 5 forming committees to finding pictures of the old neighbourhood. We’ve A Mitzvah for Us All page 6 found people living all over the world and they’ve provided clues to finding others. My Texas friend and I were a team: I used Stephen How to…Find Unhappy Facts page 6 Morse’s site www.stephenmorse.org and she used www.zabasearch.com . How to…Find the Unfindable page A Barmitzvah with a Rich Heritage page 8 As most genealogists know, finding living family very often provides clues to our ancestors. -

Centers of Marginality in Fifteenth-Century Castile: Critical

CENTERS OF MARGINALITY IN FIFTEENTH-CENTURY CASTILE: CRITICAL REEVALUATIONS OF ENRIQUE IV DE TRASTÁMARA, LEONOR LÓPEZ DE CÓRDOBA, AND ALFONSO DE CARTAGENA by BYRON H. WARNER, III (Under the Direction of Noel Fallows) ABSTRACT The concepts of center and periphery are not always mutually exclusive; one often resides within the other. This idea is central to my critical evaluations of three historical personages of fifteenth-century Castile: Enrique IV de Trastámara, doña Leonor López de Córdoba, and Alfonso de Cartagena. Each of these figures had a central political function in the kingdom, yet each also lived a dual existence at the margins of Castilian court. In this dissertation, this duality is examined using a combination of historical sources and contemporary psychology. Certain nuances in the historiographical genre of the Castilian chronicle of the fifteenth century stand out as distinct from the chronicle of previous centuries. One of these is the liberal addition of personal commentary by the chroniclers themselves, breaking to a degree with the paradigm of unadorned, historical “fact-telling.” These personal and often politically charged opinions have significantly contributed to the polarization of modern interpretations of the events and people described in these histories. The incorporation of recent psychological research allows for new readings of the chronicles and new interpretations of the mysteries surrounding Enrique IV, Leonor López, and Alfonso de Cartagena. INDEX WORDS: Fifteenth century, medieval, Middle Ages, chronicle, Enrique IV de Trastámara, doña Leonor López de Cordoba, Alfonso de Cartagena, Castile CENTERS OF MARGINALITY IN FIFTEENTH-CENTURY CASTILE: CRITICAL REEVALUATIONS OF ENRIQUE IV OF TRASTÁMARA, LEONOR LÓPEZ DE CÓRDOBA, AND ALFONSO DE CARTAGENA by BYRON H. -

Breaching the Bronze Wall: Franks at Mamluk And

Breaching the Bronze Wall Mediterranean Reconfigurations Intercultural Trade, Commercial Litigation, and Legal Pluralism Series Editors Wolfgang Kaiser (Université Paris i, Panthéon- Sorbonne) Guillaume Calafat (Université Paris i, Panthéon- Sorbonne) volume 2 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cmed Breaching the Bronze Wall Franks at Mamluk and Ottoman Courts and Markets By Francisco Apellániz LEIDEN | BOSTON The publication of this book has been funded by the European Research Council (ERC) [Advanced Grant n° 295868 “Mediterranean Reconfigurations: Intercultural Trade, Commercial Litigation, and Legal Pluralism in historical perspective”] This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: Vittore Carpaccio, Group of Soldiers and Men in Oriental Costume, Tempera on wood, 68 × 42 cm, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Apellániz Ruiz de Galarreta, Francisco Javier, 1974- author. Title: Breaching the bronze wall : Franks at Mamluk and Ottoman courts and markets / Francisco Apellániz. Description: Boston ; Leiden : Brill, 2020. | Series: Mediterranean reconfigurations, intercultural trade, commercial litigation, and legal pluralism, 2494-8772 ; volume 2 | Includes bibliographical references and index.