Historical Memory and History in the Memoirs of Iraqi Jews*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Piracy: the World's Third-Oldest Profession

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 63 Article 7 Number 63 Fall 2010 4-1-2010 Piracy: The orW ld's Third-Oldest Profession Laina Farhat-Holzman [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Farhat-Holzman, Laina (2010) "Piracy: The orldW 's Third-Oldest Profession," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 63 : No. 63 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol63/iss63/7 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Farhat-Holzman: Piracy: The World's Third-Oldest Profession Dear Readers: We are instituting with this issue a new type of article: the Historic Review Essay. The process for publishing essays will run parallel to that now existing for peer reviewed papers, but the essays will not be submitted for anonymous peer review. The point of the essays will be to present challenging or thought-provoking theories or ideas or histories that may not necessarily be congruent with prevailing scholarship. The essays will be read and scheduled by the editorial board of the journal. The first such essay is printed below. Joseph Drew HISTORIC REVIEW ESSAY Piracy: The World's Third-Oldest Profession Laina Farhat-Holzman [email protected] The world has seen a reemergence of piracy during the past few decades—an activity that had seemed obsolete. I propose exploring the origins of piracy, its most significant appearances during history, and its strange modern reincarnation. -

HANAN 2 Chedet.Co.Cc February 19, 2009 by Dr. Mahathir Mohamad

HANAN 2 Chedet.co.cc February 19, 2009 By Dr. Mahathir Mohamad Dear Hanan, 1. I think I cannot convince you on anything simply because your perception of things is not based on logic or reason but merely on your strong belief that you are always right, even if the whole world says you are wrong. 2. Jews have lived with Muslims in Muslim countries for centuries without any serious problem. 3. On the other hand in Europe, Jews were persecuted. Every now and again there would be pogroms when the Europeans would massacre Jews. The Holocaust did not happen in Muslim countries. Muslims may discriminate against Jews but did not massacre them. 4. But now you are fighting the largely Muslim Palestinians. It cannot be because of religious differences or the killing of Jews living among them. It must be because you have taken their land and expelled them from their homeland. It is therefore not a religious war. But of course as you seek sympathisers from among the non-Muslims, the Palestinians seek sympathisers among the Muslims. That still does not make the war a religious war. 5. Whether you speak Hebrew or not is not relevant. Lots of people who are not English speak English. They don't belong to England. For centuries you could speak Hebrew but remained Germans, British, French, Russians etc. 6. Lots of Jews cannot speak Hebrew but they are still Jews. Merely being able to speak Hebrew does not entitle you to claim Palestine. 7. The Jews had lived in Europe for centuries. -

Jewish Education in Baghdad: Communal Space Vs. Public Space

chapter 4 Jewish Education in Baghdad: Communal Space vs. Public Space S.R. Goldstein-Sabbah The Levant of the early twentieth century was a place of rapid political, social, and cultural transformation. This era ushered in a new, for lack of a more precise term, “modern” era for the region characterized, in part, by a burgeoning middle class and an increase in intercommunal dialogue that resulted from new forms of public space.1 The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and the combining of three former Ottoman provinces—Baghdad, Basra, and Mosul— into a new Iraqi state led to numerous challenges in unifying an ethnically and religiously diverse population and caused decades of political instability. However the British mandate and early years of the Iraqi state are also viewed as a time of religious pluralism and an attempt to build an inclusive secular state2 with the city of Baghdad as its political, cultural, and economic center. In Baghdad, as in many other Middle Eastern cities, the modern era meant the creation of new public spaces, such as chambers of commerce, modern companies, hotels, and cinemas to name a few examples.3 One type of area not often associated with public space are schools run under the auspices of religious communities. However, in Baghdad, schools run by religious authori- ties were a key factor in forging the new national identity; they often served as public spaces and as public symbols for religious communities to demonstrate their belonging to the nation. In Baghdad the first modern schools teaching secular subjects were estab- lished under the authority of religious communities. -

December Layout 1

AMERICAN & INTERNATIONAL SOCIETIES FOR YAD VASHEM Vol. 41-No. 2 ISSN 0892-1571 November/December 2014-Kislev/Tevet 5775 The American & International Societies for Yad Vashem Annual Tribute Dinner he 60th Anniversary of Yad Vashem Tribute Dinner We were gratified by the extensive turnout, which included Theld on November 16th was a very memorable many representatives of the second and third generations. evening. We were honored to present Mr. Sigmund Rolat With inspiring addresses from honoree Zigmund A. Rolat with the Yad Vashem Remembrance Award. Mr. Rolat is a and Chairman of the Yad Vashem Council Rabbi Israel Meir survivor who has dedicated his life to supporting Yad Lau — the dinner marked the 60th Anniversary of Yad Vashem and to restoring the place of Polish Jewry in world Vashem. The program was presided over by dinner chairman history. He was instrumental in establishing the newly Mark Moskowitz, with the Chairman of the American Society opened Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw. for Yad Vashem Leonard A. Wilf giving opening remarks. SIGMUND A. ROLAT: “YAD VASHEM ENSHRINES THE MILLIONS THAT WERE LOST” e are often called – and even W sometimes accused of – being obsessed with memory. The Torah calls on us repeatedly and command- ingly: Zakhor – Remember. Even the least religious among us observe this particular mitzvah – a true corner- stone of our identity: Zakhor – Remember – and logically L’dor V’dor – From generation to generation. The American Society for Yad Vashem has chosen to honor me with the Yad Vashem Remembrance Award. I am deeply grateful and moved to receive this honor. -

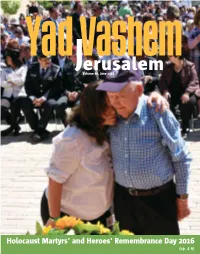

Jerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016

Yad VaJerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016 Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Day 2016 (pp. 4-9) Yad VaJerusalemhem Contents Volume 80, Sivan 5776, June 2016 Inauguration of the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on the Holocaust in the Soviet Union ■ 2-3 Published by: Highlights of Holocaust Remembrance Day 2016 ■ 4-5 Students Mark Holocaust Remembrance Day Through Song, Film and Creativity ■ 6-7 Leah Goldstein ■ Remembrance Day Programs for Israel’s Chairman of the Council: Rabbi Israel Meir Lau Security Forces ■ 7 Vice Chairmen of the Council: ■ On 9 May 2016, Yad Vashem inaugurated Dr. Yitzhak Arad Torchlighters 2016 ■ 8-9 Dr. Moshe Kantor the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on ■ 9 Prof. Elie Wiesel “Whoever Saves One Life…” the Holocaust in the Soviet Union, under the Chairman of the Directorate: Avner Shalev Education ■ 10-13 auspices of its world-renowned International Director General: Dorit Novak Asper International Holocaust Institute for Holocaust Research. Head of the International Institute for Holocaust Studies Program Forges Ahead ■ 10-11 The Center was endowed by Michael and Research and Incumbent, John Najmann Chair Laura Mirilashvili in memory of Michael’s News from the Virtual School ■ 10 for Holocaust Studies: Prof. Dan Michman father Moshe z"l. Alongside Michael and Laura Chief Historian: Prof. Dina Porat Furthering Holocaust Education in Germany ■ 11 Miriliashvili and their family, honored guests Academic Advisor: Graduate Spotlight ■ 12 at the dedication ceremony included Yuli (Yoel) Prof. Yehuda Bauer Imogen Dalziel, UK Edelstein, Speaker of the Knesset; Zeev Elkin, Members of the Yad Vashem Directorate: Minister of Immigration and Absorption and Yossi Ahimeir, Daniel Atar, Michal Cohen, “Beyond the Seen” ■ 12 Matityahu Drobles, Abraham Duvdevani, New Multilingual Poster Kit Minister of Jerusalem Affairs and Heritage; Avner Prof. -

Nd Help Pizza, Pasta & Party with Tal & Roi Local Jewish Teen Stars As

Non-Profit Organization U.S. Postage PAID Norwich, CT 06360 Permit #329 Serving The Jewish Communities of Eastern Connecticut & Western R.I. CHANGE SERVICE RETURN TO: 28 Channing St., New London, CT 06320 REQUESTED VOL. XLV NO. 19 PUBLISHED BI-WEEKLY OCTOBER 11, 2019/12 TISHRI 5780 NEXT DEADLINE OCT. 18, 2019 16 PAGES HOW TO REACH US - PHONE 860-442-8062 • FAX 860-540-1475 • EMAIL [email protected] • BY MAIL: 28 CHANNING STREET, NEW LONDON, CT 06320 Local Jewish Pizza, Pasta & Party teen stars as with Tal & Roi Many people have asked recently if the Jewish Federation will be Anne Frank having its Harvest Supper and Emissary Welcome. We will absolutely be having our Emissary Welcome however, in this year of changes, in- WATERFORDrama, the drama club stead of the Harvest Supper we will have an evening of Pizza, Pasta and at Waterford High School, is proud to Party with the Young Emissaries. Mark your calendars for Thursday, present The Diary of Anne Frank. The Nov. 7 beginning at 6pm at Temple Emanu-El in Waterford. shows will take place Thursday-Sat- We will have salad along with the pizza and pasta and a gluten free urday, October 17 -19 at 7:00pm in alternative. And back by popular demand will be our traditional Har- the Waterford High School Audito- vest Supper Apple Cider and Cider Donuts for dessert and a few other rium. surprises. The show, which kicks off WA- th Some of you may have already met Tal and Roi so come join us for TERFORDrama’s 16 season, features an evening to get to know them even better. -

Tightrope Walkers: Jacqueline Shohet Kahanoff and Naïm Kattan As “Translated Men” Danielle Drori the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research

Tightrope Walkers: Jacqueline Shohet Kahanoff and Naïm Kattan as “Translated Men” Danielle Drori The Brooklyn Institute for Social Research abstract: This article examines essays and memoirs by two multilingual writers, Jacqueline Shohet Kahanoff and Naïm Kattan, who relied on different forms of trans- lation to build their literary careers during the second half of the twentieth century. It analyzes their biographical works from the perspective of “world literature studies” and the ties between literary translation, decolonization, and nation formation. Drawing on Pascale Casanova’s concept of “translated men,” the article compares Kahanoff’s and Kattan’s cases to argue that their linguistic choices reflected their political ambiv- alences, yet have never barred their readers, editors, and translators from seeing them as “belonging” to specific canons. on translated men ranslation can be as effective in effacing cultural difference as it can be in bridg- ing it. As scholars from various fields have shown, different forms of translation played a meaningful role in the long and multifaceted history of colonialism, imperialism, and Tmodern nationalism.1 In some cases, enterprises of textual exchange complemented, or simply followed, the colonization and annexation of peoples and geographical areas. In others, cul- tural colonialism manifested itself by way of establishing educational institutions in which the colonized were immersed in the language and literature of the colonizers.2 Processes of decol- onization and of gaining national independence were also often accompanied by practices of translation, with former colonies reclaiming local literatures, starting a counter-enterprise of literary translation, and reviving dormant and local languages.3 Translation may serve, in other 1 See, e.g., the anthology Sandra Bermann and Michael Wood, Nation, Language, and the Ethics of Translation (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008). -

The Dove Flyer Free

FREE THE DOVE FLYER PDF Eli Amir,Hillel Halkin | 560 pages | 18 Feb 2010 | Halban Publishers | 9781905559183 | English | London, United Kingdom The Dove Flyer by Eli Amir: | : Books The Jews The Dove Flyer Iraq. Set in Baghdad,a young man named Kabi Daniel Gad sees his family as the final person in a legacy of seventy generations in the making. His family faces the news that the Jewish community is being forced to leave Iraq and depart the land where their ancestors lived for many years. Kabi finds himself with a mission for which he is much too young but for which he nevertheless steps up to— helping find justice for Hazkel. His The Dove Flyer Abu Uri Gavrielfinally, just wants to take care of his doves in peace and pretend that good. The film strongly conveys the political ideologies, religious affinities, and cultural identities that clashed at the time and still do today around the globe. It gives us a portrait of collective loss by intersecting various family members throughout their own journeys. He flirts with romance with his aunt- by-marriage Rachelle and his friend Adnan Tawfeek Barhoum teaches Kabi that revolution and sex go hand-in-hand. He is an innocent who goes through his own awakening as he cannot hold onto the conviction behind the play on home, family, and connection that his family emphasizes as The Dove Flyer try to hold onto their homeland and the home of seventy generations of his family. Gad as Kabi gives a very strong performance as Kabi searches for answers and guidance along the way. -

Commentary… Descent, Is Editor-At-Large at the J'accuse Coalition for Justice

בס״ד cannot acknowledge עש"ק פרשת בהר ISRAEL NEWS that history at the )בחקתי בא"י( 19 Iyar 5779 May 24, 2019 expense of Mizrahi Issue number 1245 A collection of the week’s news from Israel Jews, who with so many others, From the Bet El Twinning / Israel Action Committee of regardless of skin color, shared the Jerusalem 6:55 Beth Avraham Yoseph of Toronto Congregation desire for a Jewish state long before Toronto: 8:28 the establishment of Israel. The writer, an Israeli writer and activist of Iraqi and North African Commentary… descent, is editor-at-large at the J'accuse Coalition for Justice. No, Israel isn’t a Country of Privileged and Powerful White Europeans By Hen Mazzig Can Reform’s Embrace of Al Sharpton Be Justified? Along with resurgent identity politics in the United States and Europe, By Jonathan S. Tobin there is a growing inclination to frame the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in If the Rev. Al Sharpton were truly willing to repent for his past as a terms of race. According to this narrative, Israel was established as a refuge race-baiter and inciter of anti-Semitic violence, then having him speak at a for oppressed white European Jews who in turn became oppressors of Jewish event titled a “Consultation on Conscience” might be a good idea. people of color, the Palestinians. Perhaps that’s what the Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism As an Israeli, and the son of an Iraqi Jewish mother and North African and its leader, Rabbi Jonah Pesner, thought they were doing when they Jewish father, it’s gut-wrenching to witness this shift. -

Israel: Finding the Levant Within the Mediterranean

The Levantine Review Volume 1 Number 1 (Spring 2012) ISRAEL: FINDING THE LEVANT WITHIN THE MEDITERRANEAN Rachel S. Harris Alexandra Nocke. The Place of the Mediterranean in Modern Israeli Identity. Brill 2010, Cloth $70. ISBN 9789004173248 Amy Horowitz. Mediterranean Israeli Music and the Politics of the Aesthetic. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2010. Paper $29.95. ISBN 9780814334652. Karen Grumberg. Place and Ideology in Contemporary Hebrew Literature. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2011. Cloth $39.95. ISBN 9780815632597. Zionism as a national movement sought to unite a dispersed people under a single conception of political sovereignty, with shared symbols of flag, anthem and language. Irrespective of where Jews had found a home during 2500 years of (at least symbolic) nomadic wandering, as guests in other lands, they would now return to their ancient homeland. For such an enterprise to succeed, a degree of homogenisation was required, where differences would be erased in favour of shared commonalities. These universalised conceptions for the new Jew were debated, explored, and decided upon by the leaders of the movement whose ideas were shaped by European theories of nationalism. From the beginning of the Zionist movement in the late nineteenth century and its territorialisation in Palestine, Jews faced the challenge of looking towards Europe socially and intellectually, while simultaneously attempting to situate themselves economically and physically within the landscape of the Middle East. This hybridity can be seen in a self-portrait by Shimon Korbman, a photographer working in Tel Aviv in the 1920s: Sitting on a small stool on the sand next to the sea, he faces the camera, dressed in his white tropical summer suit, an Arabic water pipe – Nargila –in his hand. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents From the Editors 3 From the President 3 From the Executive Director 4 The Iraq & Iran Issue Iran and Iraq: Demography beyond the Jewish Past 6 Sergio DellaPergola AJS, Ahmadinejad, and Me 8 Richard Kalmin Baghdad in the West: Migration and the Making of Medieval Jewish Traditions 11 Marina Rustow Jews of Iran and Rabbinical Literature: Preliminary Notes 14 Daniel Tsadik Iraqi Arab-Jewish Identities: First Body Singular 18 Orit Bashkin A Republic of Letters without a Republic? 24 Lital Levy A Fruit That Asks Questions: Michael Rakowitz’s Shipment of Iraqi Dates 28 Jenny Gheith On Becoming Persian: Illuminating the Iranian-Jewish Community 30 Photographs by Shelley Gazin, with commentary by Nasrin Rahimieh JAPS: Jewish American Persian Women and Their Hybrid Identity in America 34 Saba Tova Soomekh Engagement, Diplomacy, and Iran’s Nuclear Program 42 Brandon Friedman Online Resources for Talmud Research, Study, and Teaching 46 Heidi Lerner The Latest Limmud UK 2009 52 Caryn Aviv A Serious Man 53 Jason Kalman The Questionnaire What development in Jewish studies over the last twenty years has most excited you? 55 AJS Perspectives: The Magazine of the President Please direct correspondence to: Association for Jewish Studies Marsha Rozenblit Association for Jewish Studies University of Maryland Center for Jewish History Editors 15 West 16th Street Matti Bunzl Vice President/Publications New York, NY 10011 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Jeffrey Shandler Rachel Havrelock Rutgers University Voice: (917) 606-8249 University of Illinois at Chicago Fax: (917) 606-8222 Vice President/Program E-Mail: [email protected] Derek Penslar Web Site: www.ajsnet.org Editorial Board Allan Arkush University of Toronto Binghamton University AJS Perspectives is published bi-annually Vice President/Membership by the Association for Jewish Studies. -

At the Periphery of the Kibbutz: Palestinian and Mizrahi Interlopers

During the kibbutz movement’s now distant halcyon days, even Zionism’s most severe crit- ics succumbed to its charms. Yet what many sojourners easily overlooked amidst their euphoric discovery was that the kibbutz was markedly unwelcoming to Israel’s internal ethnic others. As the late historian Tony Judt came to recognize, “the mere fact of collective self-government, or egalitarian distribution of consumer durables, does not make you either more sophisticated or more tolerant of others. Indeed, to the extent that it contributes to At the Periphery an extraordinary smugness of self-regard, it actually reinforces the worst kind of ethnic of the Kibbutz: solipsism” (“Kibbutz,” New York Review of Books, February 11, 2010). Here I briefly sketch the Palestinian and intriguing contours of two young literary Mizrahi Interlopers protagonists, ethnic “others” whose identities clash harshly with the self-idealizing commu- in Utopia nities to which they yearn to belong. Atallah Mansour’s (b. 1934) In a New Ranen Omer-Sherman Light (B’or Hadash, 1966), the first Hebrew novel published by a Palestinian Israeli, scrutinizes the kibbutz’ willingness to live by its own values through the eyes of a lonely outsider. Born and raised in Palestine, Mansour briefly resided in a kibbutz in northern Israel. His novel highlights the poignant failures of the lofty Zionist dream of utopia even as it expresses significant empathy for those struggling on its behalf. At one starkly revealing moment, an observant kibbutz character ruefully acknowl- edges the disillusioning reality exposed in other works of the era: “We wanted to redeem the land, to protect Jewish labour and to secure peace, and it looks as if it isn’t easy to fulfill all three wishes” (63).