Athena Itonia Indigenous to Athens?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Studies Classical

Over three centuries of centuries publishing three scholarly Over Classical Studies catalog 2020 Contents Highlighted Titles 1 Online Resources 13 Reference Works 15 Greek and Latin Literature 20 Classical Reception 23 Ancient History 29 Companions In Classical Studies 31 Archaeology, Epigraphy (see page 46) (see page 23) (see page 21) and Papyrology 33 Ancient Philosophy 35 Ancient Science and Medicine 36 Late Antiquity 38 Early Christianity 39 Related Titles 43 Journals 49 Contact Info (see page 24) (see page 23) (see page 24) Brill Open Brill offers its authors the option to make (see page 26) (see page 23) (see page 27) their work freely available online in Open Access upon publication. The Brill Open publishing option enables authors to comply with new funding body and institutional requirements. The Brill Open option is available for all journals and books published under the imprints Brill and Brill Nijhoff. More details can be found at brill.com/brillopen Rights and Permissions Brill offers a journal article permission (see page 28) service using the Rightslink licensing To stay informed about Brill’s Classical Studies programs, solution. Go to the special page on the you can subscribe to one of our newsletters at: Brill website brill.com/rights for more brill.com/email-newsletters information. Brill’s Developing Countries Program You can also follow us on Twitter and on Facebook. Brill seeks to contribute to sustainable development by participating in various Facebook.com/BrillclassicalStudies Developing Countries Programs, including Research4Life, Publishers for Development Twitter.com/Brill_Classics and AuthorAID. Every year Brill also adopts a library as part of its Brill’s Adopt a Library Visit our YouTube page: Program. -

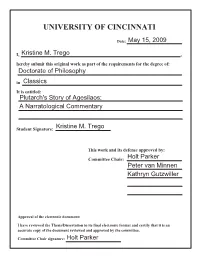

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 15, 2009 I, Kristine M. Trego , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy in Classics It is entitled: Plutarch's Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary Student Signature: Kristine M. Trego This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Holt Parker Peter van Minnen Kathryn Gutzwiller Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Holt Parker Plutarch’s Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences 2009 by Kristine M. Trego B.A., University of South Florida, 2001 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 2004 Committee Chair: Holt N. Parker Committee Members: Peter van Minnen Kathryn J. Gutzwiller Abstract This analysis will look at the narration and structure of Plutarch’s Agesilaos. The project will offer insight into the methods by which the narrator constructs and presents the story of the life of a well-known historical figure and how his narrative techniques effects his reliability as a historical source. There is an abundance of exceptional recent studies on Plutarch’s interaction with and place within the historical tradition, his literary and philosophical influences, the role of morals in his Lives, and his use of source material, however there has been little scholarly focus—but much interest—in the examination of how Plutarch constructs his narratives to tell the stories they do. -

Hades: Cornucopiae, Fertility and Death1

HADES: CORNUCOPIAE, FERTILITY AND DEATH1 Diana Burton (Victoria University of Wellington) The depiction of Hades in myth is fairly unrelenting in its gloom, and this is very much the most influential version today, as may be seen by the incarnations of Hades in modern movies; here he appears as pallid and miserable, or fiery and vengeful, but is never actually seen as enjoying himself. Hades shares the characteristics of his realm. And Hades’ domicile is seen as dim, dank and generally lacking in those things that give the greatest pleasure to the living – food, drink, sex. The fact that other gods do not enter Hades has not only to do with the antipathy between death and immortality, but also emphasises the absence of things that are under their control: Aphrodite’s love and sex, Dionysos’ wine and good cheer, the food given by Demeter. Hades is notoriously the god who receives no cult. This is not entirely correct, though it almost is. Pausanias, who is as usual our best source for this sort of thing, lists several examples of statues or altars in Greece which seem to imply some kind of cult activity, usually in someone else’s sanctuary. So for example Hades has a statue along with those of Kore and Demeter in a temple on the road near Mycenae; he has an image in the precinct of the Erinyes in Athens; he has an altar under the name of Klymenos (whom Pausanias specifically equates with Hades) in Hermione in the Argolid.2 And there are a few other places.3 The one real exception seems to have been in Elis, where he had a temple and sanctuary; although even here, the temple was opened only once a year – because, Pausanias supposes, ‘men too go down only once to Hades’ – and only the priest was permitted to enter.4 It is interesting to note that Pausanias specifically says that the Eleans are the only ones to worship (τιμσιν) Hades – which makes one wonder how he would classify the sacrifices to Klymenos. -

Dedications for the Hero Ptoios in Akraiphia, Boeotia’

Giovagnorio, F. (2018); ‘Dedications for the Hero Ptoios in Akraiphia, Boeotia’ Rosetta 22: 18 - 39 http://www.rosetta.bham.ac.uk/issue22/Giovagnorio.pdf Dedications for the Hero Ptoios in Akraiphia, Boeotia Francesca Giovagnorio Alma Mater Studiorum Bologna Abstract The paper will present all the epigraphic evidence connected to this cult, in order to understand his evolution during the centuries and, above all, his persistence in the sacred sphere even after the introduction of the cult of Apollo in the principal area of the city of Akraiphia, called Perdikovrysi. The analysis of the inscriptions will be accompanied by a short section focused on the description of the archaeological site and the literary traditions about the genealogy of the hero. This paper aims to provide a preliminary analysis of the hero Ptoios cult in Akraiphia, examined on the basis of the all the votive dedications found, and studied with a brief commentary. Keywords: votive inscriptions, Boeotia, hero Ptoios, community, Akraiphia. 18 Introduction This paper will examine the sanctuary complex of the hero Ptoios inspecting, in particular, the epigraphic production of the city of Akraphaia in Boeotia during the Late Archaic period, in order to divulge the importance of the hero in this city and to understand its symbology regarding the socio-political situation of the city at the time. The inscriptions, which will be presented below, have been examined previously with the aim of this paper being, in fact, to present them all in a unitary perspective, to make clear the formularity of dedication and also the ‘manipulation’ of the epigraphy in relation to the local and regional political dynamics. -

Numismata Graeca; Greek Coin-Types, Classified For

NUMISMATA GRAEGA GREEK COIN-TYPES CLASSIFIED FOR IMMEDIATE IDENTIFIGATION PROTAT BROTHEHS, PRINTERS, MACON (fRANCe) . NUMISMATA GRAEGA GREEK GOIN-TYPES GLASSIFIED FOR IMMEDIATE IDENTIFICATION BY L. ANSON TEXT OF PART II WA R uftk-nM.s, "X^/"eetp>oi:is, -A.rm.oiJLirs, JStandarcis, etc. ARROW, AXE, BOW, GAESTUS, CLUB, DAGGER, HARPA, JAWBONE, KNIFE, LANCE, QUIVER, SCABBARD, SLING, SPEAR, SWORD, CUIRASS, GREAVES, HELMET, SHIELD, STANDARDS, VEXILLA, TROPHIES <.0^>.T^ vo LONDON 61, REGENT STREET, W. 1911 CI RCx> pf.2 ARROW No. ARROW No. ARROW Mkiai Xo. Placic Obverse \Vt. Di.;> n.vri- PiATi: Si/i; Arrow-liead 17» Praeiieste. Buiich of grapes. AiTOw-head. ,€..85 176 B. M. Ilalv, p. 60, 21 11.40 ' Central ^ No 13. Garrucci, 3/. Italtj. /. , p. 22, No 6. - 872 18 P o 1 y r h e ro AYPHNI ON. lUiHs POAY- Arrow-head. i\. 8 Drachm. B. c. B. M. Crete, etc, liliet. r. d. .5.63 830- nium. head hnund with INHd ; b. of 20 p.67, No9. Crete 280. 19 Bull'shead; b. of d. O n Arrow-head, upwards. .E.65 ,, No 13. Y A 16 •20 Round shield, in cenlre n O Arrow-head, upwards. Ai.Ab p. t)8, No 17. of which huil's head 11 ; A Y b. of d. B. C. Babelon, Inv. Wad- •20^' Pnisias I Horse"s head. BAZIAE Arrow-head. 228- dinglon, p. 31, Bithynia. npoYZ 12 180 Noa68. 21 Uncertain. Beardless head of Ilera- EJ to r. Arrow head. AL. 7 I m hoo f, Mon. Gr., Asia Minor. kles r., Iion's skin licd 18 p. -

Political Parthenoi: the Social and Political Significance of Female Performance in Archaic Greece

Political Parthenoi: The Social and Political Significance of Female Performance in Archaic Greece Submitted by James William Smith to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics, February 2013 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. i Abstract This thesis will explore how social and political conditions in archaic Greece affected the composition of poetry for female choral performance. My primary source material will be the poetry of Alcman and Sappho. I examine the evidence suggesting that poems by both Alcman and Sappho commented on political issues, using this as a basis to argue that women in archaic Greece may have had a more vocal public presence that has previously been imagined. Rather than viewing female performance as a means of discussing purely feminine themes or reinforcing the idea of a disempowered female gender, I argue that the poetry of Alman and Sappho gives parthenoi an authoritative public voice to comment on issues in front of the watching community. Part of this authority is derived from the social value of parthenoi, who can act as economically and socially valuable points of exchange between communities, but I shall also be looking at how traditional elements of female performance genre were used to enhance female authority in archaic Sparta and Lesbos. -

Trends in Classics

2014!·!VOLUME 6!· NUMBER 2 TRENDS IN CLASSICS EDITED BY Franco Montanari, Genova Antonios Rengakos, Thessaloniki SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Alberto Bernabé, Madrid Margarethe Billerbeck, Fribourg Claude Calame, EHESS, Paris Philip Hardie, Cambridge Stephen Harrison, Oxford Stephen Hinds, U of Washington, Seattle Richard Hunter, Cambridge Christina Kraus, Yale Giuseppe Mastromarco, Bari Gregory Nagy, Harvard Theodore D. Papanghelis, Thessaloniki Giusto Picone, Palermo Kurt Raaflaub, Brown University Bernhard Zimmermann, Freiburg Brought to you by | Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin Preussischer Kulturbesitz Authenticated Download Date | 11/7/14 11:19 PM ISSN 1866-7473 ∙ e-ISSN 1866-7481 All information regarding notes for contributors, subscriptions, Open access, back volumes and orders is available online at www.degruyter.com/tic Trends in Classics, a new journal and its accompanying series of Supplementary Volumes, will pub- lish innovative, interdisciplinary work which brings to the study of Greek and Latin texts the insights and methods of related disciplines such as narratology, intertextuality, reader-response criticism, and oral poetics. Trends in Classics will seek to publish research across the full range of classical antiquity. Submissions of manuscripts for the series and the journal are welcome to be sent directly to the editors: RESPONSIBLE EDITORS Prof. Franco Montanari, Università degli Studi di Genova, Italy. franco. [email protected], Prof. Antonios Rengakos, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece. [email protected] EDITORIAL -

Grffik~~1Ill ANTI @IT~Itilli

GRIEKSCHE ANTIQUITEITEN. GRffiK~~1ill ANTI @IT~ITilli, HAN DLEIDING TOT DE KENNIS VAN HET ~TAAT~- EN BIJlONDER LEVEN DER GRIEKEN, DOOR DR. A. H. G. P. VAN DEN ES. RECTOR \' A:l II ET GYMNASIUM EN BUITJ:NGBWOON BOOGLEBRAAB AAS DE CNIVERSITEIT TE AMSTERDAM. DERDE DRUK. TE GRONINGEN BIJ J. B. WOLTERS, 1887. Stoomdrukkerij van J. B. Wolters. In dU boekje heb ik getracht zoo kort en duideltjk mogelijk een over zicht te geven van alles, wat bij het lezen van de grieksche schrijvers noodzakelijk geweten moet worden omtrellt den toestand van Gi"ieken lands bewoners in hun staats- en bijzonder leven. Dat ik Schoemanns uitvoerig werk (Gr. Alterth. 2te aufl.) tot leid draad genomen heb, zal aan ieder, die dat boek kent, dadelijk in het oog springen. Dat volgen is eehter niet slaafseh geweest. Waar ik meende van mijnen voorganger te moetell afwijken, heb ik dit ge daan. Ik reken het hier de gelegenheid niet op te geven, waar dit heeft 1l1!tats gehad, en welke overu'egingen mij hiertoe telkens gebracht hebben. - Ook was het werk van Schoemanll , dat ongeveer zesmaal grooter is dan dit werkje, "001' mijn doel te uitgebreid. Eenige ge deelten heb ik zelfs nagenoeg geheel op zijde gesehoven, nl. de ge schiehtliehe angaben ilber die verfassungett einzelner staaten en het religionswesen. Het eerste liet iI" weg, omdat Sparta en Atllene ook daar eene groote rol spelen, en juist ove/' deze beide staten in het verdet'e gedeelte uitvoerig penoeg gehandeld wordt. En den godsdienst der Grieken, hoe aanlokkelijk dit onderwerp ook door Sehoemann behandeld is, meende ik te moeten weglaten, omdat over dit onder werp reeds zoovele leerboeken bestaan, en weldra b.v. -

Ὑμετέρη Ἀρχῆθεν Γενεή: Redefining Ethnic Identity in the Cult Origins and Mythical Aetiologies of Rhianus’ Ethnographical Poetry

Graeco-Latina Brunensia 24 / 2019 / 1 https://doi.org/10.5817/GLB2019-1-13 ὑμετέρη ἀρχῆθεν γενεή: Redefining Ethnic Identity in the Cult Origins and Mythical Aetiologies of Rhianus’ Ethnographical Poetry Manolis Spanakis (University of Crete) ČLÁNKY / ARTICLES Abstract This is a meticulous survey about foundation stories, cult origins and mythical Aetia in Rhianus’ ethnographic poetry. During the Hellenistic period, interest in aetiology became very strong and there was an increasing focus on obscure and local stories from all over the Greek world and beyond. Harder (2012: p. 25) claims that as “the world became larger the need for a shared Greek past became stronger as well”. Rhianus of Crete was a Hellenistic epic poet and gram- marian of the second half of the third century BC. My contribution aims to give a fresh reread- ing of the poetic fragments and suggests that Rhianus chose places and myths that Greeks of the third century BC, and especially immigrants to Egypt, Syria or Italy, would enjoy reading because they were reminded of mainland Greece and their Greek identity. Both genealogy and aetiology leap from the crucial beginning, be that a legendary founder or one-time ritual event, to the present with a tendency to elide all time in between. The powerful aetiological drive of Rhianus’ ethnography works to break down distance and problematize the nature of epic time. In Rhianus’ aetiologies, we find a strong connection between the narrative present and the mythical past as a “betrayal” of the Homeric tradition. The absolute devotion to the past in Homer collapses in Rhianus’ aetiology, where we find a sense of cultural continuation. -

Theepigraphyand Historyofboeotia

The Epigraphy and History of Boeotia New Finds, New Prospects Edited by Nikolaos Papazarkadas leiden | boston This is a digital offprint for restricted use only | © 2014 Koninklijke Brill NV Contents Preface ix Abbreviations xi List of Contributors xii Introduction 1 section i Boeotian History: New Interpretations 1 Ethnic Identity and Integration in Boeotia: The Evidence of the Inscriptions (6th and 5th Centuries bc) 19 Hans Beck 2 Creating a Common Polity in Boeotia 45 Emily Mackil 3 ΕΧΘΟΝΔΕ ΤΑΣ ΒΟΙΩΤΙΑΣ: The Expansion of the Boeotian Koinon towards Central Euboia in the Early Third Century bc 68 Denis Knoepfler 4 Between Macedon, Achaea and Boeotia: The Epigraphy of Hellenistic Megara Revisited 95 Adrian Robu 5 A Koinon after 146? Reflections on the Political and Institutional Situation of Boeotia in the Late Hellenistic Period 119 Christel Müller section ii The New Epigraphy of Thebes 6 The Inscriptions from the Sanctuary of Herakles at Thebes: An Overview 149 Vasileios L. Aravantinos This is a digital offprint for restricted use only | © 2014 Koninklijke Brill NV viii contents 7 Four Inscribed Bronze Tablets from Thebes: Preliminary Notes 211 Angelos P. Matthaiou 8 Two New Epigrams from Thebes 223 Nikolaos Papazarkadas 9 New Inscribed Funerary Monuments from Thebes 252 Margherita Bonanno-Aravantinos section iii Boeotian Epigraphy: Beyond Thebes 10 Tlepolemos in Boeotia 313 Albert Schachter 11 Digging in Storerooms for Inscriptions: An Unpublished Casualty List from Plataia in the Museum of Thebes and the Memory of War in Boeotia -

Panels & Abstracts

THE CLASSICAL ASSOCIATION ANNUAL CONFERENCE 2018 Friday 6–Monday 9 April hosted by The School of Archaeology & Ancient History University of Leicester PANELS & ABSTRACTS Website: http://www.le.ac.uk/classical-association-2018 E-mail: [email protected] CONTENTS 1 SUBMITTED PANELS 1 2 COMPILED PANELS 14 3 PAPERS (INCLUDING RESPONSES) 16 4 POSTERS 96 5 WORKSHOPS 100 1 SUBMITTED PANELS Arranged by title. Abstracts of papers making up these panels are in section 3. [A Magnificent Seven, see under ‘M’] Aristocracy and Monetization M. 9 Convener: Gianna Stergiou (Hellenic Open University) Archaic Communities M. 11.30 Chair: Douglas Cairns (Glasgow) Convener and Chair: Kate Caraway (Liverpool) Speakers: Vayos Liapis, Richard Seaford, Gianna Stergiou, Speakers: Kate Caraway, Paul Grigsby, Serafina Nicolosi Marek Węcowski This panel interrogates the idea of the archaic Greek The wealth of the traditional Greek aristocracy, consisting community by focusing on the ways in which individuals principally in ownership of large estates, contributed interacted with one another. Traditionally archaic Greek (together with the prestige of hereditary nobility) to the communities have been approached through a establishment of personal power and status through a developmental, teleological prism that seeks to system of gift-giving. With the advent of money to the structuralise the emergence of the Greek polis. One Greek city-states, and especially with the issue and rapid result of this approach is a focus on the appearance of spread of coinage, the old system of ‘long-term organisational and institutional features—especially the transactions’ came under threat. One of the most political—of the archaic community (e.g. -

Thebes and the Boeotian Constitutions

THE DANCING FLOOR OF WAR A study of Theban imperialism within Boeotia, ca. 525–386BCE Alex Wilson A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Classics 2013 School of Art History, Classics and Religious Studies THE DANCING FLOOR OF WAR: A STUDY OF THEBAN IMPERIALISM WITHIN BOEOTIA, CA. 525–386BCE This thesis is a reexamination of Thebes’ relationship with the neighbouring Greek poleis (city states) of Boeotia in early Greek history, including but not limited to the so-called Boeotian League or Confederation. Although it is generally acknowledged that Thebes was the dominant city of Boeotia in the Archaic and Classical Periods, scholarly opinion has varied on how to classify Thebes’ dominance. At some point in the period considered here, the Boeotian states gathered themselves together into a regional collective, a confederation. The features of this union (in which Thebes was the leading participant) obscure Thebes’ ambitions to subjugate other Boeotian states. I argue here that it is appropriate to define Thebes’ relationship with Boeotia as imperialist. I begin with a methodological consideration of the application of imperialism to ancient Greek history. The thesis considers in the first chapters three stages of development in Theban imperialism: firstly an early period (ca. 525) in which Thebes encouraged nascent Boeotian ethnic identity, promoting its own position as the natural leader of Boeotia. Secondly, a period (ca. 525–447) in which a military alliance of Boeotian states developed under the leadership of Thebes. Thirdly, a period which was the earliest true form of the Boeotian Confederation, contrary to scholarship which pushes the date of the Boeotian collective government back to the sixth century.