Theepigraphyand Historyofboeotia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11Th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA an Ancient City in Greece, the Capital of Laconia and the Most Powerful State of the Peloponnese

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA AN ancient city in Greece, the capital of Laconia and the most powerful state of the Peloponnese. The city lay at the northern end of the central Laconian plain, on the right bank of the river Eurotas, a little south of the point where it is joined by its largest tributary, the Oenus (mount Kelefina). The site is admirably fitted by nature to guard the only routes by which an army can penetrate Laconia from the land side, the Oenus and Eurotas valleys leading from Arcadia, its northern neighbour, and the Langada Pass over Mt Taygetus connecting Laconia and Messenia. At the same time its distance from the sea-Sparta is 27 m. from its seaport, Gythium, made it invulnerable to a maritime attack. I.-HISTORY Prehistoric Period.-Tradition relates that Sparta was founded by Lacedaemon, son of Zeus and Taygete, who called the city after the name of his wife, the daughter of Eurotas. But Amyclae and Therapne (Therapnae) seem to have been in early times of greater importance than Sparta, the former a Minyan foundation a few miles to the south of Sparta, the latter probably the Achaean capital of Laconia and the seat of Menelaus, Agamemnon's younger brother. Eighty years after the Trojan War, according to the traditional chronology, the Dorian migration took place. A band of Dorians united with a body of Aetolians to cross the Corinthian Gulf and invade the Peloponnese from the northwest. The Aetolians settled in Elis, the Dorians pushed up to the headwaters of the Alpheus, where they divided into two forces, one of which under Cresphontes invaded and later subdued Messenia, while the other, led by Aristodemus or, according to another version, by his twin sons Eurysthenes and Procles, made its way down the Eurotas were new settlements were formed and gained Sparta, which became the Dorian capital of Laconia. -

Classical Studies Classical

Over three centuries of centuries publishing three scholarly Over Classical Studies catalog 2020 Contents Highlighted Titles 1 Online Resources 13 Reference Works 15 Greek and Latin Literature 20 Classical Reception 23 Ancient History 29 Companions In Classical Studies 31 Archaeology, Epigraphy (see page 46) (see page 23) (see page 21) and Papyrology 33 Ancient Philosophy 35 Ancient Science and Medicine 36 Late Antiquity 38 Early Christianity 39 Related Titles 43 Journals 49 Contact Info (see page 24) (see page 23) (see page 24) Brill Open Brill offers its authors the option to make (see page 26) (see page 23) (see page 27) their work freely available online in Open Access upon publication. The Brill Open publishing option enables authors to comply with new funding body and institutional requirements. The Brill Open option is available for all journals and books published under the imprints Brill and Brill Nijhoff. More details can be found at brill.com/brillopen Rights and Permissions Brill offers a journal article permission (see page 28) service using the Rightslink licensing To stay informed about Brill’s Classical Studies programs, solution. Go to the special page on the you can subscribe to one of our newsletters at: Brill website brill.com/rights for more brill.com/email-newsletters information. Brill’s Developing Countries Program You can also follow us on Twitter and on Facebook. Brill seeks to contribute to sustainable development by participating in various Facebook.com/BrillclassicalStudies Developing Countries Programs, including Research4Life, Publishers for Development Twitter.com/Brill_Classics and AuthorAID. Every year Brill also adopts a library as part of its Brill’s Adopt a Library Visit our YouTube page: Program. -

Agricultural Practices in Ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman Period

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Hellenic University: IHU Open Access Repository Agricultural practices in ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman period Evangelos Kamanatzis SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies January 2018 Thessaloniki – Greece Student Name: Evangelos Kamanatzis SID: 2201150001 Supervisor: Prof. Manolis Manoledakis I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. January 2018 Thessaloniki - Greece Abstract This dissertation was written as part of the MA in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies at the International Hellenic University. The aim of this dissertation is to collect as much information as possible on agricultural practices in Macedonia from prehistory to Roman times and examine them within their social and cultural context. Chapter 1 will offer a general introduction to the aims and methodology of this thesis. This chapter will also provide information on the geography, climate and natural resources of ancient Macedonia from prehistoric times. We will them continue with a concise social and cultural history of Macedonia from prehistory to the Roman conquest. This is important in order to achieve a good understanding of all these social and cultural processes that are directly or indirectly related with the exploitation of land and agriculture in Macedonia through time. In chapter 2, we are going to look briefly into the origins of agriculture in Macedonia and then explore the most important types of agricultural products (i.e. -

The Eastern Boeotia Archaeological Project Is a Synergasia of The

EBAP 2007 Report to Teiresias The Eastern Boeotia Archaeological Project is a synergasia of the Canadian Institute in Greece (Brendan Burke, University of Victoria, Bryan Burns, University of Southern California, and Susan Lupack, University College London) and Vassilis Aravantinos (Director of the Thebes Museum and the 9th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities). The long-term goals of the Eastern Boeotia Archaeological Project (EBAP) are to document and interpret the evidence for the land use, settlement patterns and burial practices resulting from the human occupation of eastern Boeotia over an extended chronological period. We have located our study specifically on the plains surrounding the modern villages of Arma, Eleon, and Tanagra, which are bounded by the heights of Mount Teumessos and the Soros range along the south and the Ipatos Mountains on the north, partially because of the intrinsically interesting sites they contain (Eleon and Tanagra) and partially because this area connected the Boeotian center of Thebes to the eastern sea and was therefore a major route for external contact, Our primary research interests focus on developments during the Late Bronze Age, for which evidence in the region is clearly present, yet our methods of study include a broader analysis of the region's long-term history. We are therefore pursuing documentation and study of all periods. Our initial field work in June 2007 proved very successful in terms of locating, collecting, and analyzing surface material which we found to represent activity from the Neolithic through early modern periods. In 2008 we plan to expand our collection zones, refine our interpretation of the ceramic evidence, continue mapping architectural features on the acropolis of Eleon and elsewhere, and to document the funerary landscapes of both Tanagra and Eleon. -

The Military Policy of the Hellenistic Boiotian League

The Military Policy of the Hellenistic Boiotian League Ruben Post Department of History and Classical Studies McGill University, Montreal December, 2012 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree Master of Arts ©Ruben Post, 2012. Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................. 3 Abrégé ............................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ 5 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 7 Sources .........................................................................................................................11 Chapter One .....................................................................................................................16 Agriculture and Population in Late Classical and Hellenistic Boiotia .........................16 The Fortification Building Program of Epameinondas ................................................31 Conclusion ...................................................................................................................43 Chapter Two ....................................................................................................................48 -

Euboea and Athens

Euboea and Athens Proceedings of a Colloquium in Memory of Malcolm B. Wallace Athens 26-27 June 2009 2011 Publications of the Canadian Institute in Greece Publications de l’Institut canadien en Grèce No. 6 © The Canadian Institute in Greece / L’Institut canadien en Grèce 2011 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Euboea and Athens Colloquium in Memory of Malcolm B. Wallace (2009 : Athens, Greece) Euboea and Athens : proceedings of a colloquium in memory of Malcolm B. Wallace : Athens 26-27 June 2009 / David W. Rupp and Jonathan E. Tomlinson, editors. (Publications of the Canadian Institute in Greece = Publications de l'Institut canadien en Grèce ; no. 6) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-9737979-1-6 1. Euboea Island (Greece)--Antiquities. 2. Euboea Island (Greece)--Civilization. 3. Euboea Island (Greece)--History. 4. Athens (Greece)--Antiquities. 5. Athens (Greece)--Civilization. 6. Athens (Greece)--History. I. Wallace, Malcolm B. (Malcolm Barton), 1942-2008 II. Rupp, David W. (David William), 1944- III. Tomlinson, Jonathan E. (Jonathan Edward), 1967- IV. Canadian Institute in Greece V. Title. VI. Series: Publications of the Canadian Institute in Greece ; no. 6. DF261.E9E93 2011 938 C2011-903495-6 The Canadian Institute in Greece Dionysiou Aiginitou 7 GR-115 28 Athens, Greece www.cig-icg.gr THOMAS G. PALAIMA Euboea, Athens, Thebes and Kadmos: The Implications of the Linear B References 1 The Linear B documents contain a good number of references to Thebes, and theories about the status of Thebes among Mycenaean centers have been prominent in Mycenological scholarship over the last twenty years.2 Assumptions about the hegemony of Thebes in the Mycenaean palatial period, whether just in central Greece or over a still wider area, are used as the starting point for interpreting references to: a) Athens: There is only one reference to Athens on a possibly early tablet (Knossos V 52) as a toponym a-ta-na = Ἀθήνη in the singular, as in Hom. -

Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period Ryan

Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period by Ryan Anthony Boehm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Emily Mackil, Chair Professor Erich Gruen Professor Mark Griffith Spring 2011 Copyright © Ryan Anthony Boehm, 2011 ABSTRACT SYNOIKISM, URBANIZATION, AND EMPIRE IN THE EARLY HELLENISTIC PERIOD by Ryan Anthony Boehm Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology University of California, Berkeley Professor Emily Mackil, Chair This dissertation, entitled “Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period,” seeks to present a new approach to understanding the dynamic interaction between imperial powers and cities following the Macedonian conquest of Greece and Asia Minor. Rather than constructing a political narrative of the period, I focus on the role of reshaping urban centers and regional landscapes in the creation of empire in Greece and western Asia Minor. This period was marked by the rapid creation of new cities, major settlement and demographic shifts, and the reorganization, consolidation, or destruction of existing settlements and the urbanization of previously under- exploited regions. I analyze the complexities of this phenomenon across four frameworks: shifting settlement patterns, the regional and royal economy, civic religion, and the articulation of a new order in architectural and urban space. The introduction poses the central problem of the interrelationship between urbanization and imperial control and sets out the methodology of my dissertation. After briefly reviewing and critiquing previous approaches to this topic, which have focused mainly on creating catalogues, I point to the gains that can be made by shifting the focus to social and economic structures and asking more specific interpretive questions. -

Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean Culture

Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture By Antonije Shkokljev Slave Nikolovski – Katin Translated from Macedonian to English and edited By Risto Stefov Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2013 by Antonije Shkokljev, Slave Nikolovski – Katin & Risto Stefov e-book edition 2 Index Index........................................................................................................3 COMMON HISTORY AND FUTURE ..................................................5 I - GEOGRAPHICAL CONFIGURATION OF THE BALKANS.........8 II - ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERIES .........................................10 III - EPISTEMOLOGY OF THE PANNONIAN ONOMASTICS.......11 IV - DEVELOPMENT OF PALEOGRAPHY IN THE BALKANS....33 V – THRACE ........................................................................................37 VI – PREHISTORIC MACEDONIA....................................................41 VII - THESSALY - PREHISTORIC AEOLIA.....................................62 VIII – EPIRUS – PELASGIAN TESPROTIA......................................69 IX – BOEOTIA – A COLONY OF THE MINI AND THE FLEGI .....71 X – COLONIZATION -

(Pelasgians/Pelasgi/Pelasti/Pelišti) – the Archaic Mythical Pelasgo/Stork-People from Macedonia

Basil Chulev • ∘ ⊕ ∘ • Pelasgi/Balasgi, Belasgians (Pelasgians/Pelasgi/Pelasti/Pelišti) – the Archaic Mythical Pelasgo/Stork-people from Macedonia 2013 Contents: Introduction ................................................................................................................... 5 Macedonians from Pella and Pelasgians from Macedon – origin of the Pelasgians ....... 16 Religion of the Pelasgians …………………..…………………………………..……… 32 Pelasgian language and script .......................................................................................... 39 Archaeological, Etymological, Mythological, and Genetic evidence of Pelasgic origin of Macedonians .................................................................................................................... 52 References ........................................................................................................................ 64 Introduction All the Macedonians are familiar with the ancient folktale of 'Silyan the Stork' (Mkd.latin: Silyan Štrkot, Cyrillic: Сиљан Штркот). It is one of the longest (25 pages) and unique Macedonian folktales. It was recorded in the 19th century, in vicinity of Prilep, Central Macedonia, a territory inhabited by the most direct Macedonian descendents of the ancient Bryges and Paionians. The notion of Bryges appear as from Erodot (Lat. Herodotus), who noted that the Bryges lived originally in Macedonia, and when they moved to Asia Minor they were called 'Phryges' (i.e. Phrygians). Who was Silyan? The story goes: Silyan was banished -

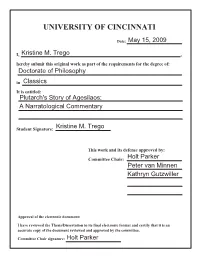

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 15, 2009 I, Kristine M. Trego , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy in Classics It is entitled: Plutarch's Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary Student Signature: Kristine M. Trego This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Holt Parker Peter van Minnen Kathryn Gutzwiller Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Holt Parker Plutarch’s Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences 2009 by Kristine M. Trego B.A., University of South Florida, 2001 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 2004 Committee Chair: Holt N. Parker Committee Members: Peter van Minnen Kathryn J. Gutzwiller Abstract This analysis will look at the narration and structure of Plutarch’s Agesilaos. The project will offer insight into the methods by which the narrator constructs and presents the story of the life of a well-known historical figure and how his narrative techniques effects his reliability as a historical source. There is an abundance of exceptional recent studies on Plutarch’s interaction with and place within the historical tradition, his literary and philosophical influences, the role of morals in his Lives, and his use of source material, however there has been little scholarly focus—but much interest—in the examination of how Plutarch constructs his narratives to tell the stories they do. -

Professor Michael Scott Department of Classics, University of Warwick, Gibbet Hill Rd, Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK [email protected]

Professor Michael Scott Department of Classics, University of Warwick, Gibbet Hill Rd, Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK [email protected] www.michaelscottweb.com EMPLOYMENT 2020-Present Director of the Warwick Institute of Engagement, University of Warwick, UK 2018-Present Professor of Classics and Ancient History, University of Warwick, UK 2014-2018 Associate Professor of Classics and Ancient History, University of Warwick, UK 2012-2014 Assistant Professor of Classics and Ancient History, University of Warwick, UK 2011-2014 Research Associate, Darwin College, Cambridge University, UK 2009-2013 Affiliated Lecturer, Faculty of Classics, Cambridge University, UK 2007-2011 Moses and Mary Finley Research Fellow in Ancient History, Darwin College, Cambridge University, UK AWARDS 2021 Classical Association Prize – awarded to the individual who has done the most to raise the profile of Classics in the public eye 2019 Principal Fellow of the Higher Education Academy 2019 Fellow of the Royal Historical Society 2017 Leverhulme Research Fellowship 2017 National Teaching Fellow (highest award for teaching in UK Higher Education) 2016 Warwick Award in Teaching Excellence (WATE) 2015 Honorary Citizenship of Delphi in recognition of worldwide impact of scholarship on site 2015 University of Warwick Outstanding Community Contribution Award 2015 Senior Fellowship of the Higher Education Academy _______________________________________________________________________________________ EXPERIENCE 2020-Present Director of Warwick Institute of Engagement, University -

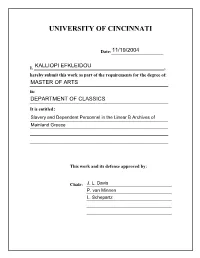

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ SLAVERY AND DEPENDENT PERSONNEL IN THE LINEAR B ARCHIVES OF MAINLAND GREECE A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Classical Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences 2004 by Kalliopi Efkleidou B.A., Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 2001 Committee Chair: Jack L. Davis ABSTRACT SLAVERY AND DEPENDENT PERSONNEL IN THE LINEAR B ARCHIVES OF MAINLAND GREECE by Kalliopi Efkleidou This work focuses on the relations of dominance as they are demonstrated in the Linear B archives of Mainland Greece (Pylos, Tiryns, Mycenae, and Thebes) and discusses whether the social status of the “slave” can be ascribed to any social group or individual. The analysis of the Linear B tablets demonstrates that, among the lower-status people, a social group that has been generally treated by scholars as internally undifferentiated, there were differentiations in social status and levels of dependence. A set of conditions that have been recognized as being of central importance to the description of the