PLUTARCH's Life of Agesilaosm Response to Sources in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

Index Note: page numbers in italics denote tables, maps, or illustrations Abdera 74 Cleomenes 237 ; coins 159, 276 , Abu Simbel 297 277, 279 ; food production 121, 268, Abydos 286 272 ; imports 268 ; Kleoitas 109 ; Achaea/Achaeans: Aigialos 213 ; Naucratis 269–271 ; pottery 191 ; basileus 128, 129, 134 ; Sparta 285 ; trade 268, 272 colonization 100, 104, 105, 107–108, Aegium 88, 91, 108 115, 121 ; democracy 204 ; Aelian 4, 186, 188 dialect 44 ; ethnos 91 ; Aeneas 109, 129 Herodotus 91 ; heroes 73, 108 ; Aeolians 45 , 96–97, 122, 292, 307 ; Homer 52, 172, 197, 215 ; dialect group 44, 45, 46 Ionians 50 ; migration 44, 45 , 50, Aeschines 86, 91, 313, 314–315 96 ; pottery 119 ; as province 68 ; Aeschylus: Persians 287, 308 ; Seven relocation 48 ; warrior tombs 49 Against Thebes 162 ; Suppliant Achilles 128, 129, 132, 137, 172, 181, Maidens 204 216 ; shield of 24, 73, 76, 138–139 Aetolia/Aetolians 20 ; dialect 299 ; Acrae 38 , 103, 110 Erxadieis 285 ; ethnos 91, 92 ; Acraephnium 279 poleis 93 ; pottery 50 ; West Acragas 38 , 47 ; democracy 204 ; Locris 20 foundation COPYRIGHTED 104, 197 ; Phalaris 144 ; Aëtos MATERIAL 62 Theron 149, 289 ; tyranny 150 Africanus, Sextus Julius 31 Adrastus 162 Agamemnon: Aeolians 97 ; anax 129 ; Aegimius 50, 51 Argos 182 ; armor 173 ; Aegina 3 ; Argos 3, 5 ; Athens 183, basileus 128, 129 ; scepter 133 ; 286, 287 ; captured 155 ; Schliemann 41 ; Thersites 206 A History of the Archaic Greek World: ca. 1200–479 BCE, Second Edition. Jonathan M. Hall. © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2014 by John Wiley & Sons, -

Offprint from Antike Kunst, Volume 59, 2016 ALEX R. KNODELL, SYLVIAN

ALEX R. KNODELL, SYLVIAN FACHARD, KALLIOPI PAPANGELI THE 2015 MAZI ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT: REGIONAL SURVEY IN NORTHWEST ATTICA (GREECE) offprint from antike kunst, volume 59, 2016 THE 2015 MAZI ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT: REGIONAL SURVEY IN NORTHWEST ATTICA (GREECE) Alex R. Knodell, Sylvian Fachard, Kalliopi Papangeli The Mazi Archaeological Project (MAP) is a dia- Survey areas and methods chronic regional survey of the Mazi Plain (Northwest Attica, Greece), operating as a synergasia between the In 2015 we conducted fieldwork in three zones: Areas Ephorate of Antiquities of West Attika, Pireus, and b, c, and e (fig. 1). Area a was the focus during the 2014 Islands and the Swiss School of Archaeology in Greece. field season3, between Ancient Oinoe and the Mazi This small mountain plain is characterized by its critical Tower on the eastern outskirts of Modern Oinoe. Area b location on a major land route between central and corresponds to the Kouloumbi Plain, just south of the southern Greece, and on the Attic-Boeotian borders. Mazi Plain and connected to it via a short passage named Territorial disputes in these borderlands are attested from Bozari. Area c is immediately north of Area a, in the the Late Archaic period1 and the sites of Oinoe and northeastern part of the survey area, immediately adja- Eleutherai have marked importance for the study of cent to the modern delimitation between Attica and Boe- Attic-Boeotian topography, mythology, and religion. otia. Area e is the western end of the Mazi Plain, and in- Our approach to regional history extends well beyond cludes the settlement and fortress of Eleutherai, at the the Classical past to include prehistoric precursors, as mouth of the Kaza Pass, as well as the small Prophitis well as the later history of this part of Greece. -

Female Property Ownership and Status in Classical and Hellenistic Sparta

Female Property Ownership and Status in Classical and Hellenistic Sparta Stephen Hodkinson University of Manchester 1. Introduction The image of the liberated Spartiate woman, exempt from (at least some of) the social and behavioral controls which circumscribed the lives of her counterparts in other Greek poleis, has excited or horrified the imagination of commentators both ancient and modern.1 This image of liberation has sometimes carried with it the idea that women in Sparta exercised an unaccustomed influence over both domestic and political affairs.2 The source of that influence is ascribed by certain ancient writers, such as Euripides (Andromache 147-53, 211) and Aristotle (Politics 1269b12-1270a34), to female control over significant amounts of property. The male-centered perspectives of ancient writers, along with the well-known phenomenon of the “Spartan mirage” (the compound of distorted reality and sheer imaginative fiction regarding the character of Spartan society which is reflected in our overwhelmingly non-Spartan sources) mean that we must treat ancient images of women with caution. Nevertheless, ancient perceptions of their position as significant holders of property have been affirmed in recent modern studies.3 The issue at the heart of my paper is to what extent female property-holding really did translate into enhanced status and influence. In Sections 2-4 of this paper I shall approach this question from three main angles. What was the status of female possession of property, and what power did women have directly to manage and make use of their property? What impact did actual or potential ownership of property by Spartiate women have upon their status and influence? And what role did female property-ownership and status, as a collective phenomenon, play within the crisis of Spartiate society? First, however, in view of the inter-disciplinary audience of this volume, it is necessary to a give a brief outline of the historical context of my discussion. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Art and Royalty in Sparta of the 3Rd Century B.C

HESPERIA 75 (2006) ART AND ROYALTY Pages 203?217 IN SPARTA OF THE 3RD CENTURY B.C. ABSTRACT a The aim of this paper is to demonstrate that revival of the arts in Sparta b.c. was during the 3rd century owed mainly to royal patronage, and that it was inspired by Alexander s successors, the Seleukids and the Ptolemies in particular. The tumultuous transition from the traditional Spartan dyarchy to a and to its dominance Hellenistic-style monarchy, Sparta's attempts regain in the P?loponn?se (lost since the battle of Leuktra in 371 b.c.), are reflected in the of the hero Herakles as a role model promotion pan-Peloponnesian at for the single king the expense of the Dioskouroi, who symbolized dual a kingship and had limited, regional appeal. INTRODUCTION was Spartan influence in the P?loponn?se dramatically reduced after the battle of Leuktra in 371 b.c.1 The history of Sparta in the 3rd century b.c. to ismarked by intermittent efforts reassert Lakedaimonian hegemony.2 A as a means to tendency toward absolutism that end intensified the latent power struggle between the Agiad and Eurypontid royal houses, leading to the virtual abolition of the traditional dyarchy in the reign of the Agiad Kleomenes III (ca. 235-222 b.c.), who appointed his brother Eukleides 1. For the battle of Leuktra and its am to and Ellen Millen 2005.1 grateful Graham Shipley Paul Cartledge and see me to am consequences, Cartledge 2002, and Ellen Millender for inviting der for historical advice. I also 251-259. -

Classical Studies Classical

Over three centuries of centuries publishing three scholarly Over Classical Studies catalog 2020 Contents Highlighted Titles 1 Online Resources 13 Reference Works 15 Greek and Latin Literature 20 Classical Reception 23 Ancient History 29 Companions In Classical Studies 31 Archaeology, Epigraphy (see page 46) (see page 23) (see page 21) and Papyrology 33 Ancient Philosophy 35 Ancient Science and Medicine 36 Late Antiquity 38 Early Christianity 39 Related Titles 43 Journals 49 Contact Info (see page 24) (see page 23) (see page 24) Brill Open Brill offers its authors the option to make (see page 26) (see page 23) (see page 27) their work freely available online in Open Access upon publication. The Brill Open publishing option enables authors to comply with new funding body and institutional requirements. The Brill Open option is available for all journals and books published under the imprints Brill and Brill Nijhoff. More details can be found at brill.com/brillopen Rights and Permissions Brill offers a journal article permission (see page 28) service using the Rightslink licensing To stay informed about Brill’s Classical Studies programs, solution. Go to the special page on the you can subscribe to one of our newsletters at: Brill website brill.com/rights for more brill.com/email-newsletters information. Brill’s Developing Countries Program You can also follow us on Twitter and on Facebook. Brill seeks to contribute to sustainable development by participating in various Facebook.com/BrillclassicalStudies Developing Countries Programs, including Research4Life, Publishers for Development Twitter.com/Brill_Classics and AuthorAID. Every year Brill also adopts a library as part of its Brill’s Adopt a Library Visit our YouTube page: Program. -

EUROPEAN SOCIAL CHARTER the GOVERNMENT of GREECE • Follow up to Collective Complaints • Complementary Information on Article

28/08/2015 RAP/Cha/GRC/25(2015) EUROPEAN SOCIAL CHARTER 25th National Report on the implementation of the European Social Charter submitted by THE GOVERNMENT OF GREECE Follow up to Collective Complaints Complementary information on Articles 11§2 and 13§4 (Conclusions 2013) __________ Report registered by the Secretariat on 28 August 2015 CYCLE XX-4 (2015) 25th Greek Report on the European Social Charter Follow-up to the decisions of the European Committee of Social Rights relating to Collective Complaints (2000 – 2012) Ministry of Labour, Social Security & Social Solidarity May 2015 25th Greek Report on the European Social Charter TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Collective Complaint 8/2000 “Quaker Council for European Affairs v. Greece” .......... 4 2. Collective Complaints (a) 15/2003, “European Roma Rights Centre [ERRC] v. Greece” & (b) 49/2008, “International Centre for the Legal Protection for Human Rights – [INTERIGHTS] v. Greece” ........................................................................................................ 8 3. Collective Complaint 17/2003 “World Organisation against Torture [OMCT] v. Greece” ................................................................................................................................. 12 4. Collective Complaint 30/2005 “Marangopoulos Foundation for Human Rights v. Greece” ................................................................................................................................. 19 5. Collective Complaint “General Federation of Employees of the National Electric -

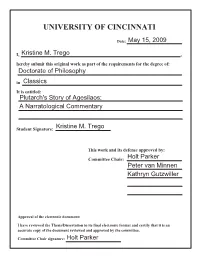

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 15, 2009 I, Kristine M. Trego , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy in Classics It is entitled: Plutarch's Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary Student Signature: Kristine M. Trego This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Holt Parker Peter van Minnen Kathryn Gutzwiller Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Holt Parker Plutarch’s Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences 2009 by Kristine M. Trego B.A., University of South Florida, 2001 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 2004 Committee Chair: Holt N. Parker Committee Members: Peter van Minnen Kathryn J. Gutzwiller Abstract This analysis will look at the narration and structure of Plutarch’s Agesilaos. The project will offer insight into the methods by which the narrator constructs and presents the story of the life of a well-known historical figure and how his narrative techniques effects his reliability as a historical source. There is an abundance of exceptional recent studies on Plutarch’s interaction with and place within the historical tradition, his literary and philosophical influences, the role of morals in his Lives, and his use of source material, however there has been little scholarly focus—but much interest—in the examination of how Plutarch constructs his narratives to tell the stories they do. -

Alex R. Knodell, Sylvian Fachard, Kalliopi Papangeli

ALEX R. KNODELL, SYLVIAN FACHARD, KALLIOPI PAPANGELI THE 2015 MAZI ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT: REGIONAL SURVEY IN NORTHWEST ATTICA (GREECE) offprint from antike kunst, volume 59, 2016 THE 2015 MAZI ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROJECT: REGIONAL SURVEY IN NORTHWEST ATTICA (GREECE) Alex R. Knodell, Sylvian Fachard, Kalliopi Papangeli The Mazi Archaeological Project (MAP) is a dia- Survey areas and methods chronic regional survey of the Mazi Plain (Northwest Attica, Greece), operating as a synergasia between the In 2015 we conducted fieldwork in three zones: Areas Ephorate of Antiquities of West Attika, Pireus, and b, c, and e (fig. 1). Area a was the focus during the 2014 Islands and the Swiss School of Archaeology in Greece. field season3, between Ancient Oinoe and the Mazi This small mountain plain is characterized by its critical Tower on the eastern outskirts of Modern Oinoe. Area b location on a major land route between central and corresponds to the Kouloumbi Plain, just south of the southern Greece, and on the Attic-Boeotian borders. Mazi Plain and connected to it via a short passage named Territorial disputes in these borderlands are attested from Bozari. Area c is immediately north of Area a, in the the Late Archaic period1 and the sites of Oinoe and northeastern part of the survey area, immediately adja- Eleutherai have marked importance for the study of cent to the modern delimitation between Attica and Boe- Attic-Boeotian topography, mythology, and religion. otia. Area e is the western end of the Mazi Plain, and in- Our approach to regional history extends well beyond cludes the settlement and fortress of Eleutherai, at the the Classical past to include prehistoric precursors, as mouth of the Kaza Pass, as well as the small Prophitis well as the later history of this part of Greece. -

Torresson Umn 0130E 21011.Pdf

The Curious Case of Erysichthon A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Elizabeth Torresson IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Advisor: Nita Krevans December 2019 © Elizabeth Torresson 2019 Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank the department for their support and especially the members of my committee: Nita Krevans, Susanna Ferlito, Jackie Murray, Christopher Nappa, and Melissa Harl Sellew. The seeds of this dissertation were planted in my senior year of college when Jackie Murray spread to me with her contagious enthusiasm a love of Hellenistic poetry. Without her genuine concern for my success and her guidance in those early years, I would not be where I am today. I also owe a shout-out to my undergraduate professors, especially Robin Mitchell-Boyask and Daniel Tompkins, who inspired my love of Classics. At the University of Minnesota, Nita Krevans took me under her wing and offered both emotional and intellectual support at various stages along the way. Her initial suggestions, patience, and encouragement allowed this dissertation to take the turn that it did. I am also very grateful to Christopher Nappa and Melissa Harl Sellew for their unflagging encouragement and kindness over the years. It was in Melissa’s seminar that an initial piece of this dissertation was begun. My heartfelt thanks also to Susanna Ferlito, who graciously stepped in at the last minute and offered valuable feedback, and to Susan Noakes, for offering independent studies so that I could develop my interest in Italian language and literature. -

An Allied History of the Peloponnesian League: Elis, Tegea, and Mantinea

An Allied History of the Peloponnesian League: Elis, Tegea, and Mantinea By James Alexander Caprio B.A. Hamilton College, 1994 M.A. Tufts University, 1997 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Classical, Near Eastern, and Religious Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA January, 2005 © James A. Caprio, 2005 Abstract Elis, Tegea, and Mantinea became members of the Peloponnesian League at its inception in 506, although each had concluded an alliance with Sparta much earlier. The initial arrangement between each city-state and Sparta was reciprocal and membership in the League did not interfere with their individual development. By the fifth century, Elis, Mantinea, and Tegea had created their own symmachies and were continuing to expand within the Peloponnesos. Eventually, the prosperity and growth of these regional symmachies were seen by Sparta as hazardous to its security. Hostilities erupted when Sparta interfered with the intent to dismantle these leagues. Although the dissolution of the allied leagues became an essential factor in the preservation of Sparta's security, it also engendered a rift between its oldest and most important allies. This ultimately contributed to the demise of Spartan power in 371 and the termination of the Peloponnesian League soon thereafter. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ii Table of Contents iii List of Maps iv List of Abbreviations v Acknowledgements viii Introduction • 1 Chapter One: Elis 20 Chapter Two: Tegea and southern Arkadia 107 Chapter Three: Mantinea and northern Arkadia 181 Conclusion 231 Bibliography , 234 iii Maps Map 1: Elis 21 Map 2: Tegean Territory 108 Map 3: The Peloponnesos 109 Map 4: Phigalia 117 Map 5: Mantinea and Tegea 182 Map 6: Mantinea and its environs 182 Abbreviations Amit, Poleis M. -

Schedule of Meetings for Affiliated Groups

144TH APA ANNUAL MEETING ABSTRACTS WASHINGTON STATE CONVENTION CENTER January 3-6, 2013 Seattle, WA ii PREFACE The abstracts in this volume appear in the form submitted by their authors without editorial intervention. They are arranged in the same order as the Annual Meeting Program. An index by name at the end of the volume is provided. This is the thirty first volume of Abstracts published by the Association in as many years, and suggestions of improvements in future years are welcome. Again this year, the Program Committee has invited affiliated groups holding sessions at the Annual Meeting to submit abstracts for publication in this volume. The following groups have published abstracts this year. AFFILIATED GROUPS American Association for Neo-Latin Studies American Classical League American Society of Greek and Latin Epigraphy American Society of Papyrologists Eta Sigma Phi Friends of Numismatics International Plutarch Society International Society for Neoplatonic Studies Lambda Classical Caucus Medieval Latin Studies Group Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Society for Ancient Medicine and Pharmacy Society for Ancient Mediterranean Religions Society for Late Antiquity Women’s Classical Caucus The Program Committee thanks the authors of these abstracts for their cooperation in making the timely production of this volume possible. 2012 ANNUAL MEETING PROGRAM COMMITTEE MEMBERS Joseph Farrell, Chair Christopher A. Faraone Kirk Freudenburg Maud Gleason Corinne O. Pache Adam D. Blistein (ex officio) Heather H. Gasda (ex officio) iii iv