Art and Royalty in Sparta of the 3Rd Century B.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

Index Note: page numbers in italics denote tables, maps, or illustrations Abdera 74 Cleomenes 237 ; coins 159, 276 , Abu Simbel 297 277, 279 ; food production 121, 268, Abydos 286 272 ; imports 268 ; Kleoitas 109 ; Achaea/Achaeans: Aigialos 213 ; Naucratis 269–271 ; pottery 191 ; basileus 128, 129, 134 ; Sparta 285 ; trade 268, 272 colonization 100, 104, 105, 107–108, Aegium 88, 91, 108 115, 121 ; democracy 204 ; Aelian 4, 186, 188 dialect 44 ; ethnos 91 ; Aeneas 109, 129 Herodotus 91 ; heroes 73, 108 ; Aeolians 45 , 96–97, 122, 292, 307 ; Homer 52, 172, 197, 215 ; dialect group 44, 45, 46 Ionians 50 ; migration 44, 45 , 50, Aeschines 86, 91, 313, 314–315 96 ; pottery 119 ; as province 68 ; Aeschylus: Persians 287, 308 ; Seven relocation 48 ; warrior tombs 49 Against Thebes 162 ; Suppliant Achilles 128, 129, 132, 137, 172, 181, Maidens 204 216 ; shield of 24, 73, 76, 138–139 Aetolia/Aetolians 20 ; dialect 299 ; Acrae 38 , 103, 110 Erxadieis 285 ; ethnos 91, 92 ; Acraephnium 279 poleis 93 ; pottery 50 ; West Acragas 38 , 47 ; democracy 204 ; Locris 20 foundation COPYRIGHTED 104, 197 ; Phalaris 144 ; Aëtos MATERIAL 62 Theron 149, 289 ; tyranny 150 Africanus, Sextus Julius 31 Adrastus 162 Agamemnon: Aeolians 97 ; anax 129 ; Aegimius 50, 51 Argos 182 ; armor 173 ; Aegina 3 ; Argos 3, 5 ; Athens 183, basileus 128, 129 ; scepter 133 ; 286, 287 ; captured 155 ; Schliemann 41 ; Thersites 206 A History of the Archaic Greek World: ca. 1200–479 BCE, Second Edition. Jonathan M. Hall. © 2014 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2014 by John Wiley & Sons, -

Marina Gavryushkina UC Berkeley Art History 2013

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics Title The Persian Alexander: The Numismatic Portraiture of the Pontic Dynasty Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xh6g8nn Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics, 2(1) ISSN 2373-7115 Author Gavryushkina, Marina Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Gavryushkina 1 The Persian Alexander: The Numismatic Portraiture of the Pontic Dynasty Marina Gavryushkina UC Berkeley Art History 2013 Abstract: Hellenistic coinage is a popular topic in art historical research as it is an invaluable resource of information about the political relationship between Greek rulers and their subjects. However, most scholars have focused on the wealthier and more famous dynasties of the Ptolemies and the Seleucids. Thus, there have been considerably fewer studies done on the artistic styles of the coins of the smaller outlying Hellenistic kingdoms. This paper analyzes the numismatic portraiture of the kings of Pontus, a peripheral kingdom located in northern Anatolia along the shores of the Black Sea. In order to evaluate the degree of similarity or difference in the Pontic kings’ modes of representation in relation to the traditional royal Hellenistic style, their coinage is compared to the numismatic depictions of Alexander the Great of Macedon. A careful art historical analysis reveals that Pontic portrait styles correlate with the individual political motivations and historical circumstances of each king. Pontic rulers actively choose to diverge from or emulate the royal Hellenistic portrait style with the intention of either gaining support from their Anatolian and Persian subjects or being accepted as legitimate Greek sovereigns within the context of international politics. -

Female Property Ownership and Status in Classical and Hellenistic Sparta

Female Property Ownership and Status in Classical and Hellenistic Sparta Stephen Hodkinson University of Manchester 1. Introduction The image of the liberated Spartiate woman, exempt from (at least some of) the social and behavioral controls which circumscribed the lives of her counterparts in other Greek poleis, has excited or horrified the imagination of commentators both ancient and modern.1 This image of liberation has sometimes carried with it the idea that women in Sparta exercised an unaccustomed influence over both domestic and political affairs.2 The source of that influence is ascribed by certain ancient writers, such as Euripides (Andromache 147-53, 211) and Aristotle (Politics 1269b12-1270a34), to female control over significant amounts of property. The male-centered perspectives of ancient writers, along with the well-known phenomenon of the “Spartan mirage” (the compound of distorted reality and sheer imaginative fiction regarding the character of Spartan society which is reflected in our overwhelmingly non-Spartan sources) mean that we must treat ancient images of women with caution. Nevertheless, ancient perceptions of their position as significant holders of property have been affirmed in recent modern studies.3 The issue at the heart of my paper is to what extent female property-holding really did translate into enhanced status and influence. In Sections 2-4 of this paper I shall approach this question from three main angles. What was the status of female possession of property, and what power did women have directly to manage and make use of their property? What impact did actual or potential ownership of property by Spartiate women have upon their status and influence? And what role did female property-ownership and status, as a collective phenomenon, play within the crisis of Spartiate society? First, however, in view of the inter-disciplinary audience of this volume, it is necessary to a give a brief outline of the historical context of my discussion. -

Cleopatra II and III: the Queens of Ptolemy VI and VIII As Guarantors of Kingship and Rivals for Power

Originalveröffentlichung in: Andrea Jördens, Joachim Friedrich Quack (Hg.), Ägypten zwischen innerem Zwist und äußerem Druck. Die Zeit Ptolemaios’ VI. bis VIII. Internationales Symposion Heidelberg 16.-19.9.2007 (Philippika 45), Wiesbaden 2011, S. 58–76 Cleopatra II and III: The queens of Ptolemy VI and VIII as guarantors of kingship and rivals for power Martina Minas-Nerpel Introduction The second half of the Ptolemaic period was marked by power struggles not only among the male rulers of the dynasty, but also among its female members. Starting with Arsinoe II, the Ptolemaic queens had always been powerful and strong-willed and had been a decisive factor in domestic policy. From the death of Ptolemy V Epiphanes onwards, the queens controlled the political developments in Egypt to a still greater extent. Cleopatra II and especially Cleopatra III became all-dominant, in politics and in the ruler-cult, and they were often depicted in Egyptian temple- reliefs—more often than any of her dynastic predecessors and successors. Mother and/or daughter reigned with Ptolemy VI Philometor to Ptolemy X Alexander I, from 175 to 101 BC, that is, for a quarter of the entire Ptolemaic period. Egyptian queenship was complementary to kingship, both in dynastic and Ptolemaic Egypt: No queen could exist without a king, but at the same time the queen was a necessary component of kingship. According to Lana Troy, the pattern of Egyptian queenship “reflects the interaction of male and female as dualistic elements of the creative dynamics ”.1 The king and the queen functioned as the basic duality through which regeneration of the creative power of the kingship was accomplished. -

The Roles of Solon in Plato's Dialogues

The Roles of Solon in Plato’s Dialogues Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Samuel Ortencio Flores, M.A. Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Bruce Heiden, Advisor Anthony Kaldellis Richard Fletcher Greg Anderson Copyrighy by Samuel Ortencio Flores 2013 Abstract This dissertation is a study of Plato’s use and adaptation of an earlier model and tradition of wisdom based on the thought and legacy of the sixth-century archon, legislator, and poet Solon. Solon is cited and/or quoted thirty-four times in Plato’s dialogues, and alluded to many more times. My study shows that these references and allusions have deeper meaning when contextualized within the reception of Solon in the classical period. For Plato, Solon is a rhetorically powerful figure in advancing the relatively new practice of philosophy in Athens. While Solon himself did not adequately establish justice in the city, his legacy provided a model upon which Platonic philosophy could improve. Chapter One surveys the passing references to Solon in the dialogues as an introduction to my chapters on the dialogues in which Solon is a very prominent figure, Timaeus- Critias, Republic, and Laws. Chapter Two examines Critias’ use of his ancestor Solon to establish his own philosophic credentials. Chapter Three suggests that Socrates re- appropriates the aims and themes of Solon’s political poetry for Socratic philosophy. Chapter Four suggests that Solon provides a legislative model which Plato reconstructs in the Laws for the philosopher to supplant the role of legislator in Greek thought. -

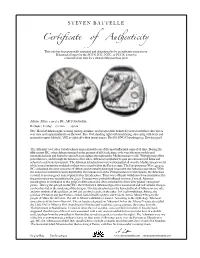

Ceificate of Auenticity

S T E V E N B A T T E L L E Ce!ificate of Au"enticity This coin has been personally inspected and determined to be an authentic ancient coin . If deemed a forgery by the ACCS, IGC, NGC, or PCGS, it may be returned at any time for a refund of the purchase price. Athens, Attica, 449-404 BC, AR Tetradrachm B076961 / U02697 17.1 Gm 25 mm Obv: Head of Athena right, wearing earring, necklace, and crested Attic helmet decorated with three olive leaves over visor and a spiral palmette on the bowl. Rev: Owl standing right with head facing, olive sprig with berry and crescent in upper left field, AOE to right; all within incuse square. Kroll 8; SNG Copenhagen 31; Dewing 1591-8 The Athenian “owl” silver tetradrachm is unquestionably one of the most influential coins of all time. During the fifth century BC, when Athens emerged as the greatest of all Greek cities, owls were the most widely used international coin and helped to spread Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean world. With the help of her powerful navy, and through the taxation of her allies, Athens accomplished to gain pre-eminance in Hellas and achieved a celebrated prosperity. The Athenian tetradrachms were well-accepted all over the Mediterranean world, while several imitations modeled on them were issued within the Persian state. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) exhausted the silver resources of Athens and eventually destroyed irreparably the Athenian supremacy. With the mines lost and their treasury depleted by the ruinous cost of the Pelloponesian war with Sparta, the Athenians resorted to an emergency issue of plated silver tetradrachms. -

The Cambridge Ancient History

THE CAMBRIDGE ANCIENT HISTORY SECOND EDITION VOLUME VII PART I The Hellenistic World Edited by F. W. W ALBANK F.B.A. Emerit1u Projeuor, former!J Profmor of Anrienl History and C!t111ieal Ar<haeology, Univmi!J of Live~pool A. E. ASTIN Profmor of Antient History, The Q11een'1 Univtr.ri!J, Btlfast M. W. FRED ERIKSEN R. M. OGI LVIE CAMBRIDGE -~ UNIVERSITY PRESS CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, S:io Paulo, Delhi Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Bujlding, Cambridge, CB2 8Ru, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org [nformacion on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521234450 ©Cambridge University Press i984 This publication is in copyright. Subject to smurory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the wrircen permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1928 Second edition 1984 Eleventh printing 2008 Primed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Library ofCongress catalogue card number; 75-85719 British Library Cataloguing in Publication data The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 7 Pt. I: The Helleniscic World, r. History, Ancient 1. Walbank, F. W . .930 D57 ISBN 978-0-521-23445-0 hardback ISBN 978-0-521-85073-5 set Cambridge U niversity Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy ofURL; for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guraranree that any content on su~ websites is, or will remain, a.ccurare or appropriate. -

The Christianisation of Adulis in Light of the Material Evidence

chapter 17 The Christianisation of Adulis in Light of the Material Evidence Serena Massa and Caterina Giostra 1 The Archaeological Research in the Ancient Town of Adulis The site of Adulis is located on the south-western coast of the Red Sea, in the well-protected bay of Zula, about 40 km south of Massawa, Eritrea.1 In the ancient world it was one of the most important ports connecting East Africa and the Mediterranean along the spice trade route from India. The Adulis commercial vocation was probably already active in the Pharaonic era, in the context of the traffic in precious materials not found in Egypt and sought in the Land of Punt.2 From the size of village3 and oppidum4 reported by the sources in the second half of the first century CE, an increasing development and importance of the site until the Byzantine period is concomitant with the rise of the Aksumite kingdom, of which Adulis represented the gate to the sea.5 1 An independent state since 1993, in antiquity the area was part of the same context of the highland territories that are currently included within the borders of Ethiopia. 2 The location of Adulis can be included in the area of the Land of Punt, identified in the regions bordering the southern Red Sea and perhaps coinciding with the locality of WDDT recorded in the geographical list of the 18th Dynasty. Archaeological levels dating to the lat- ter half of the second millennium–early first millennium BCE were documented by archae- ological excavations: Adulis in this period is considered part of the Afro-Arabian cultural complex, which extends from southern Arabian regions to the Eritrean plateau: R. -

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11Th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA an Ancient City in Greece, the Capital of Laconia and the Most Powerful State of the Peloponnese

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA AN ancient city in Greece, the capital of Laconia and the most powerful state of the Peloponnese. The city lay at the northern end of the central Laconian plain, on the right bank of the river Eurotas, a little south of the point where it is joined by its largest tributary, the Oenus (mount Kelefina). The site is admirably fitted by nature to guard the only routes by which an army can penetrate Laconia from the land side, the Oenus and Eurotas valleys leading from Arcadia, its northern neighbour, and the Langada Pass over Mt Taygetus connecting Laconia and Messenia. At the same time its distance from the sea-Sparta is 27 m. from its seaport, Gythium, made it invulnerable to a maritime attack. I.-HISTORY Prehistoric Period.-Tradition relates that Sparta was founded by Lacedaemon, son of Zeus and Taygete, who called the city after the name of his wife, the daughter of Eurotas. But Amyclae and Therapne (Therapnae) seem to have been in early times of greater importance than Sparta, the former a Minyan foundation a few miles to the south of Sparta, the latter probably the Achaean capital of Laconia and the seat of Menelaus, Agamemnon's younger brother. Eighty years after the Trojan War, according to the traditional chronology, the Dorian migration took place. A band of Dorians united with a body of Aetolians to cross the Corinthian Gulf and invade the Peloponnese from the northwest. The Aetolians settled in Elis, the Dorians pushed up to the headwaters of the Alpheus, where they divided into two forces, one of which under Cresphontes invaded and later subdued Messenia, while the other, led by Aristodemus or, according to another version, by his twin sons Eurysthenes and Procles, made its way down the Eurotas were new settlements were formed and gained Sparta, which became the Dorian capital of Laconia. -

Ancient Greek Coins

Ancient Greek Coins Notes for teachers • Dolphin shaped coins. Late 6th to 5th century BC. These coins were minted in Olbia on the Black Sea coast of Ukraine. From the 8th century BC Greek cities began establishing colonies around the coast of the Black Sea. The mixture of Greek and native currencies resulted in a curious variety of monetary forms including these bronze dolphin shaped items of currency. • Silver stater. Aegina c 485 – 480 BC This coin shows a turtle symbolising the naval strength of Aegina and a punch mark In Athens a stater was valued at a tetradrachm (4 drachms) • Silver staterAspendus c 380 BC This shows wrestlers on one side and part of a horse and star on the other. The inscription gives the name of a city in Pamphylian. • Small silver half drachm. Heracles wearing a lionskin is shown on the obverse and Zeus seated, holding eagle and sceptre on the reverse. • Silver tetradrachm. Athens 450 – 400 BC. This coin design was very poular and shows the goddess Athena in a helmet and has her sacred bird the Owl and an olive sprig on the reverse. Coin values The Greeks didn’t write a value on their coins. Value was determined by the material the coins were made of and by weight. A gold coin was worth more than a silver coin which was worth more than a bronze one. A heavy coin would buy more than a light one. 12 chalkoi = 1 Obol 6 obols = 1 drachm 100 drachma = 1 mina 60 minas = 1 talent An unskilled worker, like someone who unloaded boats or dug ditches in Athens, would be paid about two obols a day. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Nabis and Flamininus on the Argive Revolutions of 198 and 197 B.C. , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 28:2 (1987:Summer) P.213

ECKSTEIN, A. M., Nabis and Flamininus on the Argive Revolutions of 198 and 197 B.C. , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 28:2 (1987:Summer) p.213 Nabis and Flamininus on the Argive Revolutions of 198 and 197 B.C. A. M. Eckstein N THE SUMMER of 19 5 a. c. T. Quinctius Flamininus and the Greek I allies of Rome went to war against N abis of Sparta. The official cause of the war was Nabis' continued occupation of Argos, the great city of the northeastern Peloponnese. 1 A strong case can be made that the liberation of Argos was indeed the crucial and sincere goal of the war,2 although the reasons for demanding Nabis' with drawal from Argos may have been somewhat more complex.3 Nabis was soon blockaded in Sparta itself and decided to open negotiations for peace. Livy 34.3lfprovides us with a detailed account of the sub sequent encounter between N abis and Flamininus in the form of a debate over the justice of the war, characterized by contradictory assertions about the history of Sparta's relations with Rome and the recent history of Argos. Despite the acrimony, a preliminary peace agreement was reached but was soon overturned by popular resis tance to it in Sparta. So the war continued, with an eventual Roman 1 Cf. esp. Liv. 34.22.10-12, 24.4, 32.4f. 2 See now E. S. GRUEN, The Hellenistic World and the Coming of Rome II (Berkeley/Los Angeles [hereafter 'Gruen']) 450-55, who finds the propaganda of this war, with its consistent emphasis on the liberation of Argos as a matter of honor both for Rome and for Flamininus, likely to have some basis in fact.