Large Housing Estates of Berlin, Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aircraft Noise in Berlin Affects Quality of Life Even Outside the Airport Grounds

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Eibich, Peter; Kholodilin, Konstantin; Krekel, Christian; Wagner, Gert G. Article Aircraft noise in Berlin affects quality of life even outside the airport grounds DIW Economic Bulletin Provided in Cooperation with: German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin) Suggested Citation: Eibich, Peter; Kholodilin, Konstantin; Krekel, Christian; Wagner, Gert G. (2015) : Aircraft noise in Berlin affects quality of life even outside the airport grounds, DIW Economic Bulletin, ISSN 2192-7219, Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW), Berlin, Vol. 5, Iss. 9, pp. 127-133 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/107601 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu AIRCRAFT NOISE AND QUALITY OF LIFE Aircraft Noise in Berlin Affects Quality of Life Even Outside the Airport Grounds By Peter Eibich, Konstantin Kholodilin, Christian Krekel and Gert G. -

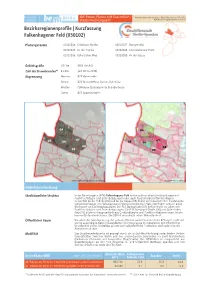

Kurzfassung Falkenhagener Feld

Abt. Bauen, Planen und Gesundheit | Kontakt: Karsten Kruse (Bau 2 Stapl A8) | (030) 90279-2191 | Stadtentwicklungsamt [email protected] Bezirksregionenprofile | Kurzfassung Falkenhagener Feld (050102) Planungsräume 05010204 Griesinger Straße 05010207 Darbystraße 05010205 An der Tränke 05010208 Germersheimer Platz 05010206 Gütersloher Weg 05010209 An der Kappe Gebietsgröße 697 ha (RBS-Fläche) Zahl der Einwohnenden* 41.435 (am 30.06.2018) Abgrenzung Norden: BZR Hakenfelde Süden: BZR Brunsbütteler Damm, Bahnlinie Westen: Falkensee (Landesgrenze Brandenburg) Osten: BZR Spandau Mitte 04 04 05 07 07 06 05 06 08 08 09 09 Digitale farbige Orthophotos 2017 (FIS-Broker) Ausschnitt ÜK50 (FIS-Broker) Gebietsbeschreibung Stadträumliche Struktur In der Bezirksregion (BZR) Falkenhagener Feld finden sich vor allem Großsiedlungen mit Punkthochhäuser und Zeilenbebauungen aber auch freistehende Einfamilienhäuser. In den PLR An der Tränke (05) und An der Kappe (09) finden sich hauptsächlich freistehende Einfamilienhäuser. Im Planungsraum (PLR) Germersheimer Platz (08) finden sich vor allem Blockrand- und Zeilenbebauungen. Der PLR Darbystraße (07) definiert sich vor allem mit Punkthochhäuser und Zeilenbebauungen. Die PLR Griesinger Straße (04) und Gütersloher Weg (06) bestehen hauptsächlich aus Großsiedlungen und Punkthochhäusern sowie freiste- henden Einfamilienhäusern. Die BZR ist ein nahezu reiner Wohnstandort. Öffentlicher Raum Vor allem der Spektegrünzug, der sich von Westen nach Osten durch die BZR zieht, stellt mit seinen ausgiebigen -

“More”? How Store Owners and Their Businesses Build Neighborhood

OFFERING “MORE”? HOW STORE OWNERS AND THEIR BUSINESSES BUILD NEIGHBORHOOD SOCIAL LIFE Vorgelegt von MA Soz.-Wiss. Anna Marie Steigemann Geboren in München, Deutschland von der Fakultät VI – Planen, Bauen, Umwelt der Technischen Universität Berlin zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktorin der Philosophie in Soziologie - Dr. phil - Genehmigte Dissertation Promotionsausschuss: Vorsitzende: Prof. Dr. Angela Million Gutachterin I: Prof. Dr. Sybille Frank Gutachter II: Prof. Dr. John Mollenkopf Gutachter III: Prof. Dr. Dietrich Henckel Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 10. August 2016 Berlin 2017 Author’s Declaration Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis and that this thesis and the work presented in it are my own and have been generated by me as the result of my own original research. In addition, I hereby confirm that the thesis at hand is my own written work and that I have used no other sources and aids other than those indicated. The author herewith confirms that she possesses the copyright rights to all parts of the scientific work, and that the publication will not violate the rights of third parties, in particular any copyright and personal rights of third parties. Where I have used thoughts from external sources, directly or indirectly, published or unpublished, this is always clearly attributed. All passages, which are quoted from publications, the empirical fieldwork, or paraphrased from these sources, are indicated as such, i.e. cited or attributed. The questionnaire and interview transcriptions are attached in the version that is not publicly accessible. This thesis was not submitted in the same or in a substantially similar version, not even partially, to another examination board and was not published elsewhere. -

Integriertes Entwicklungskonzept Für Das Gebiet Falkenhagener Feld West (Quartiersbeauftragte: Gesop Mbh)

Entwicklungskonzept Falkenhagener Feld – West Oktober 2005 Anlage 1 j Integriertes Entwicklungskonzept für das Gebiet Falkenhagener Feld West (Quartiersbeauftragte: GeSop mbH) 1. Kurzcharakteristik des Gebiets Die Großsiedlung Falkenhagener Feld wurde aufgrund ihrer Größenordnung durch das Stadtteilmanagementverfahren in zwei Teilgebiete unterteilt. Aus diesem Grund gibt es vielfach Statistiken/Daten, die über die Abgrenzung der Teilgebiete hinausgehen. Die Großsiedlung Falkenhagener Feld – West befindet sich beidseitig der Falkenseer Chaussee, westlich der Zeppelinstraße, östlich des „Kiesteiches“, südlich der Pionierstraße und nördlich der Spektewiesen. Bebauungsstruktur Seit dem Jahre 1963 (Baubeginn) wurde auf dem Gebiet des ehemaligen Kleingartenlandes eine Großsiedlung gebaut mit Großsiedlungseinheiten der frühen 60er und 70er Jahre, aus Zeilenbauten, Einzelhäusern und bis zu siebzehngeschossigen Punkthochhäusern. Ab 1990 wurde das Falkenhagener Feld durch Geschosswohnungsbau nachverdichtet; die großzügigen grünen Zwischenräume reduzierten sich. Neben dem Geschosswohnungsbau erstrecken sich auch Siedlungseinheiten aus Einfamilienhäusern durch das gesamte Gebiet. Heute ist die Siedlung (Bereich Ost und West)) mit 56 EW/ha (Vergleich: Spandau 23,5 EW/ha) ein dicht besiedeltes Gebiet, verfügt aber auf Grund der Gesamtgröße, dem relativ hohen Grünanteil und trotz der Nachverdichtung über aufgelockerte Baustrukturen. Mit rund 10 000 Wohneinheiten und knapp 20 000 Einwohnern ist die gesamte Großsiedlung Falkenhagener Feld nach dem Märkischen Viertel und der Gropiusstadt die drittgrößte Großsiedlung in Berlin (West). Die Siedlung wird durch die Osthavelländische Eisenbahn in die beiden Bereiche Falkenhagener Feld Ost und West geteilt, die jeweils als eigenständige Gebiete für das Stadtteilmanagementverfahren ausgewiesen wurden. Wohnungsbestand Das Falkenhagener Feld West verfügt im Geschosswohnungsbau über knapp 4000 Wohneinheiten. Dieser Bestand hat sich in den letzten Jahren massiv verringert. Durch den Verkauf von Wohnungen sind Eigentumswohnungen entstanden. -

Einwohnerinnen Und Einwohner Im Land Berlin Am 30. Juni 2014

statistik Statistischer Berlin Brandenburg Bericht A I 5 – hj 1 / 14 Einwohnerinnen und Einwohner im Land Berlin am 30. Juni 2014 Alter Geschlecht Familienstand Migrationshintergrund Staatsangehörigkeit Religionsgemeinschaftszugehörigkeit Wohnlage Bezirk Ortsteil LOR-Bezirksregion Anteil Kinder und Jugendlicher mit Migrationshintergrund an allen Personen unter 18 Jahren in Berlin am 30. Juni 2014 nach Ortsteilen in Prozent Anteil in % Berlin: 44,7 unter 25 25 bis unter 50 50 bis unter 75 75 und mehr 0 5 10 km Grünflächen Gewässer Impressum Statistischer Bericht A I 5 – hj 1 / 14 Erscheinungsfolge: halbjährlich Erschienen im September 2014 Herausgeber Zeichenerklärung Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg 0 weniger als die Hälfte von 1 Behlertstraße 3a in der letzten besetzten Stelle, 14467 Potsdam jedoch mehr als nichts [email protected] – nichts vorhanden www.statistik-berlin-brandenburg.de … Angabe fällt später an ( ) Aussagewert ist eingeschränkt Tel. 0331 8173 - 1777 / Zahlenwert nicht sicher genug Fax 030 9028 - 4091 • Zahlenwert unbekannt oder geheim zu halten x Tabellenfach gesperrt p vorläufige Zahl r berichtigte Zahl s geschätzte Zahl Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg, Potsdam, 2014 Dieses Werk ist unter einer Creative Commons Lizenz vom Typ Namensnennung 3.0 Deutschland zugänglich. Um eine Kopie dieser Lizenz einzusehen, konsultieren Sie http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/de/ statistik Statistischer Bericht A I 5 – hj 1 / 14 Berlin BrandenburgBerlin Inhaltsverzeichnis Seite Seite Vorbemerkungen 4 3 Deutsche und ausländische Einwohnerinnen und Einwohner in Berlin seit 2003 nach Grafiken Bezirken ................................................................. 7 4 Durchschnittsalter der Einwohnerinnen und 1 Einwohnerinnen und Einwohner mit Migra- Einwohner in Berlin seit 2003 nach Bezirken tionshintergrund in Berlin am 30.06.2014 in Jahren ............................................................... -

Bericht Zur Bevölkerungsprognose Für Berlin Und Die Bezirke 2018 – 2030

Bevölkerungsprognose für Berlin und die Bezirke 2018 – 2030 Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Wohnen Ref. I A – Stadtentwicklungsplanung in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg Berlin, 10. Dez. 2019 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Vorbemerkungen und Ergebnisübersicht ……………………………………2 2. Ergebnisse für die Gesamtstadt und die Bezirke ……………………………………7 3. Prognoseannahmen und -varianten …………………………………..14 4. Anhang – Kartenmaterial …………………………………..37 1 1. Vorbemerkungen und Ergebnisübersicht 1.1 Vorbemerkung Mit der „Bevölkerungsprognose für Berlin und die Bezirke 2018 – 2030“ wird zum siebenten Mal durch die Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Wohnen eine Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung für Berlin vorgelegt. Das Wissen über künftige Tendenzen der Bevölkerungsentwicklung ist unerlässlich für die Ausrichtung von Stadtentwicklungspolitik. Hierbei dient die Prognose als Arbeitsgrundlage und Orientierungshilfe für Fachleute aus Planung und Politik. Die Bevölkerungsprognose ist sowohl auf das gesamtstädtische Planungsgeschehen ausgerichtet als auch Planungsgrundlage auf bezirklicher Ebene und für kleinere Gebietseinheiten mit spezifischen sozioökonomischen Gegebenheiten. Der zukünftige Bedarf an benötigter sozialer und technischer Infrastruktur hängt wesentlich von den demografischen Entwicklungen in einem Gebiet ab. Die damit befassten Verwaltungen und Institutionen greifen auf die Bevölkerungsprognose als Bestandteil der Planungsgrundlagen zurück. Die Prognose weist daher Ergebnisse auf Ebene der Gesamtstadt als Grundlage -

Familienzentren in Spandau

Familienzentren in Spandau Stand März 2019 Grußwort -Familienzentren- Liebe Familien, mit dieser kleinen Broschüre erhalten Sie eine Übersicht der in Spandau vorhandenen Familienzentren und deren vielfältigen Angeboten. Die Idee, ein niedrigschwelliges und jederzeit verfügbares Hilfsangebot insbesondere für Familien einzurichten, ist vor rund zehn Jahren entstanden und hat inzwischen einen festen Platz im bezirklichen Angebot für Jugend und Familie. Aus den anfänglich drei Einrichtungen wurde mit Hilfe der zuständigen Ämter, vieler freier Träger und nicht zuletzt mit vielen ehrenamtlich tätigen Bürgerinnen und Bürgern ein Netz aus jetzt neun Familienzentren gebildet. Die gute Resonanz zeigt, wie wichtig und richtig diese Bemühungen waren. Ich hoffe, dass die Familienzentren auch weiterhin gut genutzt werden und danke allen Beteiligten für Ihren Einsatz. Schauen Sie doch mal vorbei! Ihr Stephan Machulik Bezirksstadtrat für Bürgerdienste, Ordnung und Jugend Familienzentrum Villa Nova Rauchstr. 66, 13587 Berlin FiZ Falkenhagener Feld West Wasserwerkstr. 3, 13589 Berlin FiZ Falkenhagener Feld Ost Hermann-Schmidt-Weg 5, 13589 Berlin Familienzentum Kita Lasiuszeile Lasiuszeile 6, 13585 Berlin Familienzentrum Stresow Grunewaldstr. 7, 13597 Berlin Familienzentrum Rohrdamm Voltastr. 2, 13629 Berlin Familienzentrum Hermine Räcknitzer Steig 12, 13593 Berlin Familientreff Staaken Obstallee 22d, 13593 Berlin Familienzentrum Wilhelmine Weverstr 72, 13595 Berlin Ortsteil Familienzentrum Träger E-Mail Hakenfelde Villa Nova Kompaxx e.V. [email protected] Falkenhagener FiZ Humanistischer fiz-wasserwerkstrasse@ Feld Falkenhagener Feld West Verband Deutschlands humanistischekitas.de FiZ FiPP e.V. [email protected] Falkenhagener Feld Ost Familienzentrum familienzentrum-lasius@ Mitte Juwo – Kita gGmbH Kita Lasiuszeile jugendwohnen-berlin.de Familienzentrum Ev. Kirchengemeinde s.schimke@familienzentrum- Stresow St. Nikolai stresow.de Siemensstadt Familienzentrum Kompaxx e.V. -

Spandauer Tag Des Ehrenamts

Spandauer Tag des Ehrenamts 11. September 2021, 12-16 Uhr (abweichende Uhrzeiten sind vermerkt) Ausstellende Organisationen, Initiativen & Vereine Falkenhagener Feld Organisation Aktion & barriere- Kontakt Veranstaltungsort frei? Paul-Gerhardt- Infos, Beratung, Ja Andrea Dolejs Kirchengemeinde – geöffnetes Café Mail: Stadtteilzentrum im Im Spektefeld 26, Andrea.dolejs@paulgerhardtgemeinde. Falkenhagener Feld- 13589 Berlin de West, Bildungsforum & Fon: 030 373 62 53 Senior:innenprojekt Stadtteilarbeit Infos & Gespräche Ja Ingo Gust Falkenhagener Feld Kiezstube Mail: [email protected] Falkenhagener Feld, Fon: 0179 473 72 3 98 Spekteweg 48, 13583 Berlin Wilhelmstadt Organisation Aktion & barriere- Kontakt Veranstaltungsort frei? BENN in der Adamstr.40 Nein Phillip-Simon Keithel Wilhelmstadt // GesBiT 13595 Berlin Mail: [email protected] mbH Fon: 030 49 95 19 10 Gatow-Kladow Organisation Aktion & barriere- Kontakt Veranstaltungsort frei? Stadtteilzentrum Gatow Stände, Musik & Ja Gerit Probst Kladow (Träger: RKI Aktionen Mail: [email protected] BBW) Gemeindegarten der Fon: 030 36 502 125 o. 0157 357 01 259 Chance BJS gGmbH Ev. Kirchengemeinde Marina Röstel Kladow, Mail: [email protected] Kladower Damm 369, Fon: 030 50 91 80 66 14089 Berlin Willkommensbündnis Max Weithmann Gatow-Kladow Uhrzeit: 13-16 Uhr Mail: [email protected] Repaircafé vom Kladower Fon: 0157 52 85 74 77 Forum Känguru - hilft und Dr. Julia Grieb begleitet Mail: [email protected] Fon: 0178 7709388 Arbeitskreis Gatow Andreas Erben Mail: [email protected] Café Südwind Adelheid Schütz Mail: [email protected] Fon: 0171 368 25 20 Hospizdienst Andrea Langer-Fricke, Anne Boerger Christophourus e.V. Mail: mail@hospizdienst- christophorus.de Fon: 030 78 99 0602 „Wir packen´s an“ In Klärung Sportfreunde Kladow In Klärung Klimaakademie Spandau In Klärung / Kladow for Future Interkultureller Garten In Klärung Bezirkssportbund Alt-Gatow 5 Florian Harendt Spandau e.V. -

Wegweiser – Nachbarschaft Und Soziales in Neukölln Süd

Wegweiser – Nachbarschaft und Soziales in Neukölln Süd 2016 / 2017 Netzwerk Gropiusstadt Wegweiser Nachbarschaft und Soziales in Neukölln Süd Diese Broschüre erscheint bereits in der siebten überarbeiteten Auflage. Sie stellt Ihnen – den Bürgerinnen und Bürgern aus dem Süden Neuköllns – die Adressen sozialer Einrichtungen in dieser Region vor. Diese Broschüre möchte Ihnen eine Orientierungshilfe sein, Ihnen weite Wege ersparen und Sie vor allen Dingen ermun- tern, sich in Ihrer Nachbarschaft umzuschauen, wenn Sie nach einem Treffpunkt für Begegnung im Stadtteil oder nach Hilfestellung bei gesundheitlichen/persönlichen/familiären Problemen suchen. Um diese vielen interessanten Angebote sinnvoll für Sie auf- einander abzustimmen und fort zu entwickeln, haben sich im Januar 2011 über 20 Projekte als Netzwerk Gropiusstadt (NWG) zusammengeschlossen. Vertreten darin sind Beratungs-, Selbsthilfe-, Nachbarschafts-, Jugend/ Familien- und Senioren*innen einrichtungen sowie Gropiusstädter Wohnungsbauunternehmen. Viel Freude beim Durchblättern! Herausgeber: Selbsthilfe- und Stadtteilzentrum Neukölln-Süd Lipschitzallee 80, 12353 Berlin, Tel. 605 66 00, Fax 605 68 99 Redaktion: Carmen Schmidt, geschäftsführende Projekteleitung und Koordinatorin der Nachbarschaftsarbeit Neukölln-Süd Recherche und Datenbank: Nicole Franke, ehrenamtliche Mitarbeiterin Finanzierung: Senatsverwaltung Gesundheit und Soziales Datenmanagement/Layout und Herstellung: Thomas Didier, Meta Druck, [email protected] Nachbarschaft und Soziales in Neukölln-Süd Begegnungen im Stadtteil -

Senatsverwaltung Für Stadtentwicklung Und Wohnen Berlin, Den 23

Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Wohnen Berlin, den 23. April 2018 - IV B 4 - Telefon 9(0) 139 - 4860 Fax 9(0) 139 - 4801 [email protected] An den Vorsitzenden des Hauptausschusses über den Präsidenten des Abgeordnetenhauses von Berlin über Senatskanzlei - G Sen - Stadtumbau Ost und Stadtumbau West 19. Sitzung des Abgeordnetenhauses vom 14. Dezember 2017 Drucksache Nr. 18/0700 (II.B.84) – Auflagenbeschlüsse 2018/2019 9. Sitzung des Hauptausschusses am 14. Juni 2017 Bericht SenStadtWohn -IV B 4- vom 21. April 2017, rote Nr. 0383 Kapitel 1240 Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Wohnen - Wohnungswesen, Wohnungsneubau, Stadterneuerung, Soziale Stadt Titel 89362 Zuschüsse zur Förderung von Maßnahmen im Rahmen des Programms Stadtumbau Ost Ansatz 2017: 25.849.000 € Ansatz 2018: 26.872.000 € Ansatz 2019: 28.273.000 € Ist 2017: 18.909.002,52 € Verfügungsbeschränkungen: 0 € Aktuelles Ist (Stand 21.03.2018): 326.136,61 € Titel 89363 Zuschüsse zur Förderung von Maßnahmen im Rahmen des Programms Stadtumbau West Ansatz 2017: 13.317.000 € Ansatz 2018: 17.057.000 € Ansatz 2019: 19.451.000 € Ist 2017: 9.531.474,65 € Verfügungsbeschränkungen: 0 € Aktuelles Ist (Stand 21.03.2018): 128.744,52 € Der Hauptausschuss hat in seiner oben bezeichneten Sitzung Folgendes beschlossen: „Der Senat berichtet dem Hauptausschuss jährlich zum 1. Mai zu den Programmen Stadtumbau Ost und Stadtumbau West sowie zu den sog. Begegnungszonen (Evaluation Modellprojekte 5 und 6).“ - 1 - - 2 - Beschlussvorschlag Der Hauptausschuss nimmt den Bericht zur Kenntnis. Hierzu wird berichtet: Dieser Bericht umfasst die Programme Stadtumbau Ost und Stadtumbau West. Zu den Begegnungszonen wird gesondert berichtet. 1. Stadtumbau Der Stadtumbau ist nach § 171 a Baugesetzbuch (BauGB) auf die Anpassung der Siedlungsstruktur an die Erfordernisse des demografischen und wirtschaftlichen Wandels sowie des Klimaschutzes und der -anpassung ausgerichtet. -

Reference Guide No. 14

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE NO.14 THE GDR IN GERMAN ARCHIVES AGUIDE TO PRIMARY SOURCES AND RESEARCH INSTITUTIONS ON THE HISTORY OF THE SOVIET ZONE OF OCCUPATION AND THE GERMAN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC, 1945–1990 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION THE EDITORS CENTRAL ARCHIVES 1. Bundesarchiv, Abteilung DDR, Berlin ..................................................... 5 2. Bundesarchiv, Abteilung Milita¨rarchiv, Freiburg .................................. 8 3. Politisches Archiv des Auswa¨rtigen Amts, Berlin ............................... 10 4. Die Bundesbeauftragte fu¨ r die Unterlagen des Staatssicherheitsdienstes der ehemaligen Deutschen Demokratischen Republik (BStU), Zentralstelle Berlin, Abteilung Archivbesta¨nde ........ 12 5. Stiftung Archiv der Parteien und Massenorganisationen der DDR im Bundesarchiv (SAPMO), Berlin ............................................ 15 6. Archiv fu¨ r Christlich-Demokratische Politik (ACDP), Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, St. Augustin .................................................. 17 7. Archiv des Deutschen Liberalismus (ADL), Friedrich-Naumann-Stiftung, Gummersbach ............................................ 19 STATE ARCHIVES State Archives: An Overview ....................................................................... 21 8. Landesarchiv Berlin ................................................................................... 22 9. Brandenburgisches Landeshauptarchiv Potsdam ................................ 24 10. Landeshauptarchiv Schwerin ................................................................ -

The Berlin Reader

Matthias Bernt, Britta Grell, Andrej Holm (eds.) The Berlin Reader Matthias Bernt, Britta Grell, Andrej Holm (eds.) The Berlin Reader A Compendium on Urban Change and Activism Funded by the Humboldt University Berlin, the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation and the Leibniz Institute for Regional Development and Structural Planning (IRS) in Erkner. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-3-8394-2478-0. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No- Derivatives 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commer- cial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creative- commons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for commer- cial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contacting rights@ transcript-verlag.de Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. The obligation to research and clear permission lies solely with the party re-using the material. © 2013 transcript