The Berlin Reader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rechte Angriffe Dokumentiert 01. Januar 2005 Berlin-Köpenick S

Berlin, 03. Februar 2006 Rechte Angriffe dokumentiert Chronologie rechtsextremer, rassistischer, antisemitischer und schwulenfeindlicher Vorfälle in Berlin 2005 vorgelegt. Wie im vergangenen Jahr legen die Berliner Projekte gegen Rassismus, Rechtsextremismus und Antisemitismus ReachOut und apabiz e.V. der Öffentlichkeit eine gemeinsame Chronologie vor. Die Zahl der gewalttätigen Angriffe und verbalen Attacken hat sich im Vergleich zu 2004 fast verdoppelt. Zu diesem Ergebnis kommt eine Chronologie über Angriffe, die rassistisch, antisemitisch, schwulenfeindlich oder rechtsextremistisch motiviert waren. Die Zusammenstellung führt insgesamt 134 Meldungen auf, die in den Medien oder von den Opfern veröffentlicht wurden. Dabei handelte es sich in 98 Fällen um Gewalttaten (2004: 53 Gewalttaten in 71 Meldungen, 2003: 42 Gewalttaten in 66 Meldungen). Rassistisch motiviert waren davon 19 Angriffe, die damit über dem Niveau des Vorjahres liegen (2004: 16); 9 Angriffe richteten sich gegen Homosexuelle. Die meisten Angriffe – 70 von insgesamt 98, also mehr als zwei Drittel - richteten sich gegen alternative Jugendliche und junge AntifaschistInnen. In vielen Berichten werden die Angreifer als Gruppen schwarz gekleideter und vermummter Personen beschrieben, die mit großer Brutalität und teilweise deutlich geplant vorgehen. So wurde am 26. April 2005 eine Musikgruppe in ihrem Proberaum in Pankow überfallen, mit Reizgas besprüht und mit sogenannten Totschlägern zusammen geschlagen. Die Täter gingen davon aus, eine linke Punkband vor sich zu haben. Die Mehrzahl der Angriffe fanden im öffentlichen Raum und an Bahnhöfen statt, insgesamt 80. Sehr häufig sind wie im obigen Beispiel mehrere Personen von einem tätlichen Angriff betroffen. Daher zählte ReachOut im vergangenen Jahr 77 Körperverletzungen und 17 schwere Körperverletzungen sowie 74 Fälle von Nötigung, Bedrohung oder versuchter Körperverletzung. -

Technology and Urbanity in Southeast Berlin

Berlin TXL – The Technologie-Park Urban Tech Republic Berlin Humboldthain Berlin-Buch Smart Campus Siemensstadt CleanTech Marzahn Berlin Campus Charlottenburg Wirtschafts- und Wissenschafts- standort Berlin Schöneweide Berlin SÜDWEST EUREF-Campus Berlin Flughafen Tempelhof Adlershof Future will be good. Because we‘re shaping it! between companies and research, aim at tackling current challenges excellent business conditions, and like climate change as well as setting a diverse range of support services. the course for the development of The “Zukunftsorte” brand is both a technologies in the future. Ramona Pop cornerstone of Berlin’s renaissance Senator for Economics, as an industrial location as well as a The “Zukunftsorte” play a sub- © Wolf Lux Energy and Public Enterprises growth-enhancing environment for stantial role in Berlin’s economic Are you ready to shape the future? future innovation. We cooperate developing start-ups and small busi- development. Our aim is to unlock closely with our local partners to nesses, especially high-innovation their full potential for strengthen- The future is built on how we realise strengthen Berlin’s position as a companies that manage to stand ing and developing Berlin as a ideas today. For ideas to become location for business, science, and out in an increasingly diversifying business location. Read on to find a reality, they need space to grow. research, facilitating new value industry landscape. These companies out how we are working hand in This is the underlying concept of creation chains through innovative are creating a pool of competitive hand with our partners to use your Berlin’s “Zukunftsorte”, which is products and services. -

Stadtteilarbeit Im Bezirk Mitte

Stadtteilarbeit im Bezirk Mitte In unseren Nachbarschaftstreffpunkten finden Sie viele ver- Stadtteilzentrum schiedene Angebote für Jung und Alt. Hier treffen sich Nach- barinnen und Nachbarn in Kursen oder Gruppen, zu kultu- Selbsthilfe Kontaktstelle rellen Veranstaltungen, um ihre Ideen für die Nachbarschaft Nachbarschaftstreff umzusetzen, um sich beraten zu lassen oder um Räume für Familienzentrum eigene Projekte und Festivitäten anzumieten. Mehrgenerationenhaus Osloer mit Rollstuhl zugänglich Alexanderplatz Straße WC rollstuhlgerechtes WC 19 1 Begegnungsstätte Die unterschiedlichen Spandauer Straße 21 Begrifflichkeiten der Bezirksamt Mitte von Berlin 18 Nachbarschaftseinrichtungen Spandauer Str. 2 | 10178 Berlin Parkviertel liegen an den jeweiligen Tel. 242 55 66 Förderprogrammen. 22 25 17 www.berlin.de/ba-mitte WC 20 2 Kieztreff Koepjohann Wedding Koepjohann’sche Stiftung Zentrum Große Hamburger Str. 29 10115 Berlin | Tel. 30 34 53 04 4 www.koepjohann.de WC Brunnenstraße Nord 3 KREATIVHAUS Stadtteilkoordination 26 5 8 KREATIVHAUS e.V. | Fischerinsel 3 | 10179 Berlin 7 6 Tel. 238 09 13 | www.kreativhaus-tpz.de WC Brunnenstraße Nord Moabit West 10 4 Begegnungsstätte im Kiez Brunnenstraße Jahresringe Gesellschaft für Arbeit | 15 Süd und Bildung e.V. Stralsunder Str. 6 16 13355 Berlin | Tel. 464 50 36 13 www.jahresringe-ev.de/ Moabit Ost 9 begegnungsstatten.html WC 14 2 5 Begegnungsstätte Haus Bottrop 12 Alexanderplatz Selbst-Hilfe im Vor-Ruhestand e.V. Schönwalder Str. 4 | 13347 Berlin Tel. 493 36 77 | www.sh-vor-ruhestand.de WC 1 6 Familienzentrum Wattstraße Pfefferwerk Stadtkultur gGmbH | Wattstr. 16 11 | | 13355 Berlin Tel. 32 51 36 55 www.pfefferwerk.de Regierungs- WC viertel 3 7 Kiezzentrum Humboldthain Tiergarten Süd DRK-Kreisverband Wedding / Prenzlauer Berg e. -

STADTTEILPROFIL 2015 Alt-Hohenschönhausen

STADTTEILPROFIL 2015 Alt-Hohenschönhausen Süd Teil 1 – Analyse und Bewertung Wasserturm am Obersee Flusspferdsiedlung Allee-Center Gedenkstätte Hohenschönhausen Impressum Herausgeber: Bezirksamt Lichtenberg von Berlin Arbeitsgruppe Sozialraumorientierung Koordination: OE SPK L, Herr Heymann Bearbeitung: OE SPK GK G, Frau Pöhl Bildnachweis Titelseite: Bezirksamt Lichtenberg Bearbeitungsstand: 30.05.2016 Hinweis: Alle Daten, falls nicht expliziert ausgewiesen, sind mit Stand vom 31.12.2014 (Quelle: Amt für Statistik Ber- lin-Brandenburg) STADTTEILPROFIL 2015 – Alt-Hohenschönhausen Süd Inhaltsverzeichnis 0. Einleitung......................................................................................................................................... 6 1. Kurzporträt des Stadtteils – stadträumliche Struktur ........................................................................... 7 2. Demografische Struktur und Entwicklung ......................................................................................... 10 2.1 Einwohnerentwicklung ............................................................................................................ 10 2.2 Altersstruktur ......................................................................................................................... 11 2.3 Migrationshintergrund ............................................................................................................. 13 2.4 Wanderungen ....................................................................................................................... -

Aircraft Noise in Berlin Affects Quality of Life Even Outside the Airport Grounds

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Eibich, Peter; Kholodilin, Konstantin; Krekel, Christian; Wagner, Gert G. Article Aircraft noise in Berlin affects quality of life even outside the airport grounds DIW Economic Bulletin Provided in Cooperation with: German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin) Suggested Citation: Eibich, Peter; Kholodilin, Konstantin; Krekel, Christian; Wagner, Gert G. (2015) : Aircraft noise in Berlin affects quality of life even outside the airport grounds, DIW Economic Bulletin, ISSN 2192-7219, Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW), Berlin, Vol. 5, Iss. 9, pp. 127-133 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/107601 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu AIRCRAFT NOISE AND QUALITY OF LIFE Aircraft Noise in Berlin Affects Quality of Life Even Outside the Airport Grounds By Peter Eibich, Konstantin Kholodilin, Christian Krekel and Gert G. -

Kurzfassung Falkenhagener Feld

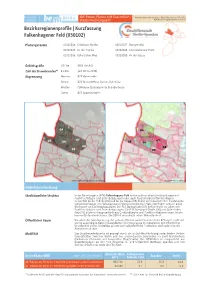

Abt. Bauen, Planen und Gesundheit | Kontakt: Karsten Kruse (Bau 2 Stapl A8) | (030) 90279-2191 | Stadtentwicklungsamt [email protected] Bezirksregionenprofile | Kurzfassung Falkenhagener Feld (050102) Planungsräume 05010204 Griesinger Straße 05010207 Darbystraße 05010205 An der Tränke 05010208 Germersheimer Platz 05010206 Gütersloher Weg 05010209 An der Kappe Gebietsgröße 697 ha (RBS-Fläche) Zahl der Einwohnenden* 41.435 (am 30.06.2018) Abgrenzung Norden: BZR Hakenfelde Süden: BZR Brunsbütteler Damm, Bahnlinie Westen: Falkensee (Landesgrenze Brandenburg) Osten: BZR Spandau Mitte 04 04 05 07 07 06 05 06 08 08 09 09 Digitale farbige Orthophotos 2017 (FIS-Broker) Ausschnitt ÜK50 (FIS-Broker) Gebietsbeschreibung Stadträumliche Struktur In der Bezirksregion (BZR) Falkenhagener Feld finden sich vor allem Großsiedlungen mit Punkthochhäuser und Zeilenbebauungen aber auch freistehende Einfamilienhäuser. In den PLR An der Tränke (05) und An der Kappe (09) finden sich hauptsächlich freistehende Einfamilienhäuser. Im Planungsraum (PLR) Germersheimer Platz (08) finden sich vor allem Blockrand- und Zeilenbebauungen. Der PLR Darbystraße (07) definiert sich vor allem mit Punkthochhäuser und Zeilenbebauungen. Die PLR Griesinger Straße (04) und Gütersloher Weg (06) bestehen hauptsächlich aus Großsiedlungen und Punkthochhäusern sowie freiste- henden Einfamilienhäusern. Die BZR ist ein nahezu reiner Wohnstandort. Öffentlicher Raum Vor allem der Spektegrünzug, der sich von Westen nach Osten durch die BZR zieht, stellt mit seinen ausgiebigen -

“More”? How Store Owners and Their Businesses Build Neighborhood

OFFERING “MORE”? HOW STORE OWNERS AND THEIR BUSINESSES BUILD NEIGHBORHOOD SOCIAL LIFE Vorgelegt von MA Soz.-Wiss. Anna Marie Steigemann Geboren in München, Deutschland von der Fakultät VI – Planen, Bauen, Umwelt der Technischen Universität Berlin zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktorin der Philosophie in Soziologie - Dr. phil - Genehmigte Dissertation Promotionsausschuss: Vorsitzende: Prof. Dr. Angela Million Gutachterin I: Prof. Dr. Sybille Frank Gutachter II: Prof. Dr. John Mollenkopf Gutachter III: Prof. Dr. Dietrich Henckel Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 10. August 2016 Berlin 2017 Author’s Declaration Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis and that this thesis and the work presented in it are my own and have been generated by me as the result of my own original research. In addition, I hereby confirm that the thesis at hand is my own written work and that I have used no other sources and aids other than those indicated. The author herewith confirms that she possesses the copyright rights to all parts of the scientific work, and that the publication will not violate the rights of third parties, in particular any copyright and personal rights of third parties. Where I have used thoughts from external sources, directly or indirectly, published or unpublished, this is always clearly attributed. All passages, which are quoted from publications, the empirical fieldwork, or paraphrased from these sources, are indicated as such, i.e. cited or attributed. The questionnaire and interview transcriptions are attached in the version that is not publicly accessible. This thesis was not submitted in the same or in a substantially similar version, not even partially, to another examination board and was not published elsewhere. -

Ausgabe 02/2018 Cbds in Berlin Ð Renaissance Der City West?

Marktbericht – Ausgabe 02/2018 CBDs in Berlin – Renaissance der City West?. Marktbericht – Ausgabe 02/2018 CBDs in Berlin Renaissance der City West? Mit dem Chanson „Heimweh nach dem Kurfürstendamm“ beschreibt Hil- degard Knef bereits 1964 den Mythos, der den Prachtboulevard umgibt. Der Kurfürstendamm bzw. die City West steht für Einkaufen, Arbeiten, Kultur und Wohnen. Aber ist der Sehnsuchtsort für Berliner und Touristen auch wieder ein ernstzunehmender Central Business District (CBD) und wie positioniert er sich im Vergleich zu den zwei weiteren Schwergewich- ten im Berliner Büromarktgefüge? Der Mythos Ku'damm entwickelte sich in den 1920er-Jahren. Schauspieler, Musiker, Schriftsteller und politisch Andersdenkende zog es in die Kaffee- häuser. Sie entwickelten einen eigenen Lebensstil, der die Gegend prägte. Nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg war die City West großflächig zerstört. Mehr als 80 Prozent des Bestandes, darunter auch die Gedächtniskirche, wurden schwer beschädigt. Durch die Teilung Berlins entwickelte sich die Gegend rund um den Bahnhof Zoo zum politischen und wirtschaftlichen Zentrum Westberlins und somit auch zum gefragten Bürostandort. Die im Krieg entstandenen Baulücken wurden zunehmend geschlossen. In den 50er und 60er Jahren entstanden Bauten, die das Erscheinungsbild heute noch prä- gen: das Bikini-Haus, der Zoo Palast, das Europa Center und das Bürohoch- haus „Hutmacher Haus“. Mit dem Fall der Berliner Mauer wurde der Kurfürstendamm erst einmal von vielen ignoriert. Investoren, Projektentwickler und Unternehmen richteten ihren Fokus fast ausschließlich auf die sogenannte City Ost – in Mitte und den östlichen Innenstadtbezirken herrschte Goldgräberstimmung. Die City West fiel in eine Art Dornröschenschlaf. Erst nach und nach verschob sich die Aufmerksamkeit wieder in Richtung Westen. Spätestens aber mit der Eröffnung des Zoofensters und des renom- mierten Hotels Waldorf Astoria im Jahr 2012 ist der Aufschwung der City West eindeutig spürbar. -

He Big “Mitte-Struggle” Politics and Aesthetics of Berlin's Post

Martin Gegner he big “mitt e-struggl e” politics and a esth etics of t b rlin’s post-r nification e eu urbanism proj ects Abstract There is hardly a metropolis found in Europe or elsewhere where the 104 urban structure and architectural face changed as often, or dramatically, as in 20 th century Berlin. During this century, the city served as the state capital for five different political systems, suffered partial destruction pós- during World War II, and experienced physical separation by the Berlin wall for 28 years. Shortly after the reunification of Germany in 1989, Berlin was designated the capital of the unified country. This triggered massive building activity for federal ministries and other governmental facilities, the majority of which was carried out in the old city center (Mitte) . It was here that previous regimes of various ideologies had built their major architectural state representations; from to the authoritarian Empire (1871-1918) to authoritarian socialism in the German Democratic Republic (1949-89). All of these époques still have remains concentrated in the Mitte district, but it is not only with governmental buildings that Berlin and its Mitte transformed drastically in the last 20 years; there were also cultural, commercial, and industrial projects and, of course, apartment buildings which were designed and completed. With all of these reasons for construction, the question arose of what to do with the old buildings and how to build the new. From 1991 onwards, the Berlin urbanism authority worked out guidelines which set aesthetic guidelines for all construction activity. The 1999 Planwerk Innenstadt (City Center Master Plan) itself was based on a Leitbild (overall concept) from the 1980s called “Critical Reconstruction of a European City.” Many critics, architects, and theorists called it a prohibitive construction doctrine that, to a certain extent, represented conservative or even reactionary political tendencies in unified Germany. -

Berlin - Wikipedia

Berlin - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berlin Coordinates: 52°30′26″N 13°8′45″E Berlin From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Berlin (/bɜːrˈlɪn, ˌbɜːr-/, German: [bɛɐ̯ˈliːn]) is the capital and the largest city of Germany as well as one of its 16 Berlin constituent states, Berlin-Brandenburg. With a State of Germany population of approximately 3.7 million,[4] Berlin is the most populous city proper in the European Union and the sixth most populous urban area in the European Union.[5] Located in northeastern Germany on the banks of the rivers Spree and Havel, it is the centre of the Berlin- Brandenburg Metropolitan Region, which has roughly 6 million residents from more than 180 nations[6][7][8][9], making it the sixth most populous urban area in the European Union.[5] Due to its location in the European Plain, Berlin is influenced by a temperate seasonal climate. Around one- third of the city's area is composed of forests, parks, gardens, rivers, canals and lakes.[10] First documented in the 13th century and situated at the crossing of two important historic trade routes,[11] Berlin became the capital of the Margraviate of Brandenburg (1417–1701), the Kingdom of Prussia (1701–1918), the German Empire (1871–1918), the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) and the Third Reich (1933–1945).[12] Berlin in the 1920s was the third largest municipality in the world.[13] After World War II and its subsequent occupation by the victorious countries, the city was divided; East Berlin was declared capital of East Germany, while West Berlin became a de facto West German exclave, surrounded by the Berlin Wall [14] (1961–1989) and East German territory. -

Public Infrastructure Project Planning in Germany: the Case of the BER Airport in Berlin-Brandenburg

Large Infrastructure Projects in Germany Between Ambition and Realities Working Paper 3 Public Infrastructure Project Planning in Germany: The Case of the BER Airport in Berlin-Brandenburg Registration I will attend: By Jobst Fiedler and Alexander Wendler This working paper is part of the research project by the Hertie School of Governance Name on Large Infrastructure Projects in Germany – Between Ambition and Realities. For further information:Position www.hertie-school.org/infrastructure The study was made possible by theInstitution friendly support of the Karl Schlecht Foundation Email Hertie School of Governance | May 2015 Accompanied by Contents 1. Introduction………………………………………………………….... 1 1.1 High-profile failure in large infrastructure projects…………………... 1 1.2 Research Question and Limitations………………………………….. 3 1.3 Hypothesis…………………………………………………………….... 4 1.4 Methods of Inquiry and Sources…………………………………….... 6 2. Megaprojects and their Inherent Problems………………………. 8 2.1 Large-scale Infrastructure Projects – an Introduction………………. 8 2.2 Empirical Performance of Large-scale Infrastructure Projects…….. 8 2.3 Drivers of Project Performance……………………………………….. 9 2.3.1 National Research Council (US Department of Energy) …………... 9 2.3.2 Miller and Lessard (IMEC Study) …………………………………….. 10 2.3.3 Flyvbjerg et al…………………………………………………………... 11 2.3.4 Mott MacDonald………………………………………………………... 14 2.3.5 Institute for Government / 2012 London Olympics………………….. 15 2.3.6 Eggers and O’Leary (If We Can Put A Man On The Moon) ………… 17 2.4 Analytical Framework for Review of BER Project…………………… 18 3. The BER Project………………………………………………………. 20 3.1 Background: The Long Road Towards a New Airport in Berlin…….. 20 3.2 BER Governance and Project Set-Up………………………………... 21 3.2.1 Against better knowledge: failure to appoint a general contractor and consequences for risk allocation………………………………… 21 3.2.2 Project Supervision and Control: deficiencies in structure and expertise levels………………………………………………………… 26 3.2.3 Financing and the Role of Banks…………………………………….. -

Integriertes Entwicklungskonzept Für Das Gebiet Falkenhagener Feld West (Quartiersbeauftragte: Gesop Mbh)

Entwicklungskonzept Falkenhagener Feld – West Oktober 2005 Anlage 1 j Integriertes Entwicklungskonzept für das Gebiet Falkenhagener Feld West (Quartiersbeauftragte: GeSop mbH) 1. Kurzcharakteristik des Gebiets Die Großsiedlung Falkenhagener Feld wurde aufgrund ihrer Größenordnung durch das Stadtteilmanagementverfahren in zwei Teilgebiete unterteilt. Aus diesem Grund gibt es vielfach Statistiken/Daten, die über die Abgrenzung der Teilgebiete hinausgehen. Die Großsiedlung Falkenhagener Feld – West befindet sich beidseitig der Falkenseer Chaussee, westlich der Zeppelinstraße, östlich des „Kiesteiches“, südlich der Pionierstraße und nördlich der Spektewiesen. Bebauungsstruktur Seit dem Jahre 1963 (Baubeginn) wurde auf dem Gebiet des ehemaligen Kleingartenlandes eine Großsiedlung gebaut mit Großsiedlungseinheiten der frühen 60er und 70er Jahre, aus Zeilenbauten, Einzelhäusern und bis zu siebzehngeschossigen Punkthochhäusern. Ab 1990 wurde das Falkenhagener Feld durch Geschosswohnungsbau nachverdichtet; die großzügigen grünen Zwischenräume reduzierten sich. Neben dem Geschosswohnungsbau erstrecken sich auch Siedlungseinheiten aus Einfamilienhäusern durch das gesamte Gebiet. Heute ist die Siedlung (Bereich Ost und West)) mit 56 EW/ha (Vergleich: Spandau 23,5 EW/ha) ein dicht besiedeltes Gebiet, verfügt aber auf Grund der Gesamtgröße, dem relativ hohen Grünanteil und trotz der Nachverdichtung über aufgelockerte Baustrukturen. Mit rund 10 000 Wohneinheiten und knapp 20 000 Einwohnern ist die gesamte Großsiedlung Falkenhagener Feld nach dem Märkischen Viertel und der Gropiusstadt die drittgrößte Großsiedlung in Berlin (West). Die Siedlung wird durch die Osthavelländische Eisenbahn in die beiden Bereiche Falkenhagener Feld Ost und West geteilt, die jeweils als eigenständige Gebiete für das Stadtteilmanagementverfahren ausgewiesen wurden. Wohnungsbestand Das Falkenhagener Feld West verfügt im Geschosswohnungsbau über knapp 4000 Wohneinheiten. Dieser Bestand hat sich in den letzten Jahren massiv verringert. Durch den Verkauf von Wohnungen sind Eigentumswohnungen entstanden.