Liberty and Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The American Experience with Diplomacy and Military Restraint I

PART I: THE AmERICAN EXPERIENCE WITH DIPLOMACY AND MILITARY RESTRAINT i. Orphaned Diplomats: The American Struggle to Match Diplomacy with Power Jeremi Suri E. Gordon Fox Professor of History and Director, European Union Center of Excellence, University of Wisconsin, Madison Benjamin Franklin spent the American Revolution in Paris. He had helped to draft the Declaration of Independence in the summer of 1776, one of the most radical documents of the eighteenth century—sparking rebellion on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Serving as a representative for the Continental Congress in France during the next decade, Franklin became a celebrity. He was the enlightened idealist from the frontier, the man of principled action who enthralled onlookers in the rigid European class societies of the 1770s and ’80s. Franklin embodied the American critique of Old World society, economy, and diplomacy. He was one of many American revolutionaries to take aim at the degenerate world of powdered wigs, fancy uniforms, and silver-service dinners where the great men of Europe decided the fate of distant societies. Franklin was a representative of the enduring American urge to replace the diplomacy of aristocrats with the openness and freedom of democrats.1 Despite his radical criticisms of aristocracy, Franklin was also a prominent participant in Parisian salons. To the consternation of John Adams and John Jay, he dined most evenings with the most conservative elements of French high society. Unlike Adams, he did not refuse to dress the part. For all his frontiers- man claims, Franklin relished high-society silver-service meals, especially if generous portions of wine were available for the guests. -

Dean G. Acheson Oral History Interview – JFK #1, 4/27/1964 Administrative Information

Dean G. Acheson Oral History Interview – JFK #1, 4/27/1964 Administrative Information Creator: Dean G(ooderham) Acheson Interviewer: Lucius D. Battle Date of Interview: April 27, 1964 Place of Interview: Washington, D.C. Length: 34 pp. Biographical Note Acheson, Secretary of State under President Harry S. Truman, talks about foreign policy matters during the John F. Kennedy administration and his advice and activities during that time. He also reads the text of several letters he wrote to JFK. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed February 15, 1965, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. Direct your questions concerning copyright to the reference staff. Transcript of Oral History Interview These electronic documents were created from transcripts available in the research room of the John F. -

History 600: Public Intellectuals in the US Prof. Ratner-Rosenhagen Office

Hannah Arendt W.E.B. DuBois Noam Chomsky History 600: Public Intellectuals in the U.S. Prof. Ratner-Rosenhagen Lecturer: Ronit Stahl Class Meetings: Office: Mosse Hum. 4112 Office: Mosse Hum. 4112 M 11 a.m.-1 p.m. email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Room: Mosse Hum. 5257 Prof. RR’s Office Hours: R.S.’s Office Hours: T 3- M 9 a.m.-11a.m. 5 p.m. This course is designed for students interested in exploring the life of the mind in the twentieth-century United States. Specifically, we will examine the life of particular minds— intellectuals of different political, moral, and social persuasions and sensibilities, who have played prominent roles in American public life over the course of the last century. Despite the common conception of American culture as profoundly anti-intellectual, we will evaluate how professional thinkers and writers have indeed been forces in American society. Our aim is to investigate the contested meaning, role, and place of the intellectual in a democratic, capitalist culture. We will also examine the cultural conditions, academic and governmental institutions, and the media for the dissemination of ideas, which have both fostered and inhibited intellectual production and exchange. Roughly the first third of the semester will be devoted to reading studies in U.S. and comparative intellectual history, the sociology of knowledge, and critical social theory. In addition, students will explore the varieties of public intellectual life by becoming familiarized with a wide array of prominent American philosophers, political and social theorists, scientists, novelists, artists, and activists. -

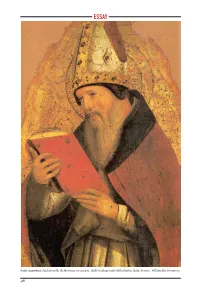

Saint Augustine, by Antonello De Messina, Circa 1472. Galleria Regionale Della Sicilia, Italy

ESSAY Caption?? Saint Augustine, by Antonello de Messina, circa 1472. Galleria Regionale della Sicilia, Italy. Source: Wikimedia Commons. 48 READING AUGUSTINE James Turner JoHnson ugustine’s influence runs deep and broad through Western Christian Adoctrine and ethics. This paper focuses on two particular examples of this influence: his thinking on political order and on just war. Augustine’s conception of political order and the Christian’s proper relation to it, developed most fully in his last and arguably most comprehensive theological work, The City of God, is central in both Catholic and mainline Protestant thinking on the political community and the proper exercise of government. Especially important in recent debate, the origins of the Christian idea of just war trace to Augustine. Exactly how Augustine has been read and understood on these topics, as well as others, has varied considerably depending on context, so the question in each and every context is how to read and understand Augustine. Paul Ramsey was right to insist, them as connected. When they fundamental problem for any in the process of developing are separated, one or another reading of Augustine on these his own understanding of just kind of distortion is the result. subjects. war, that in Christian thinking the idea of just war does not It is, of course, possible to ap- My discussion begins by exam- stand alone but is part of a com- proach either or both of these ining the use of Augustine by prehensive conception of good topics without taking account two prominent recent thinkers politics. This also describes of Augustine’s thinking or its on just war, Paul Ramsey and Augustine’s thinking. -

An Interview with Jean Bethke Elshtain

Just War, Humanitarian Intervention and Equal Regard: An Interview with Jean Bethke Elshtain Jean Bethke Elshtain is the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Professor of Social and Political Ethics at the University of Chicago. Among her books are Just War Against Terror. The Burden of American Power in a Violent World (Basic Books, 2003), Jane Addams and the Dream of American Democracy (Basic Books, 2001), Women and War (Basic Books, 1987) and Democracy on Trial (Basic Books, 1995), which Michael Walzer called ‘the work of a truly independent, deeply serious, politically engaged, and wonderfully provocative political theorist.’ The interview was conducted on 1 September 2005. Alan Johnson: Unusually for a political philosopher you have been willing to discuss the personal and familial background to your work. You have sought a voice ‘through which to traverse …particular loves and loyalties and public duties.’ Can you say something about your upbringing, as my mother would have called it, and your influences, and how these have helped to form the characteristic concerns of your political philosophy? Jean Bethke Elshtain: Well, my mother would have called it the same thing, so our mothers’ probably shared a good deal. There is always a confluence of forces at work in the ideas that animate us but upbringing is critical. In my own case this involved a very hard working, down to earth, religious, Lutheran family background. I grew up in a little village of about 180 people where everybody pretty much knew everybody else. You learn to appreciate the good and bad aspects of that. There is a tremendous sense of security but you realise that sometimes people are too nosy and poke into your business. -

Letter to Europe

LETTER TO EUROPE by Philip H Gordon In an open letter, Washington’s top Europe-watcher proposes a “new deal” to help drag transatlantic relations out of their postwar low. The future of the west is at stake EAR FRIENDS.How did it come to this? I icans and Europeans on a range of issues. The end of cannot remember a time when the gulf the cold war, the rise of US military, political and eco- between Europeans and Americans was nomic power during the 1990s, and Europe’s preoc- so wide. For the past couple of years, I cupation with the challenges of integration and Dhave argued that the Iraq crisis was a sort of “perfect enlargement, have combined to accentuate these dif- storm” unlikely to be repeated, and that many of the ferences. But we have had different strategic perspec- recent tensions resulted from the personalities and tives—and fights about strategy—for years, and that shortcomings of key actors on both sides. The never prevented us from working together towards transatlantic alliance has overcome many crises common goals. And despite the provocations from before, and given our common interests and values ideologues on both sides, this surely remains possible and the enormous challenges we face, I have been today. Leaders still have options, and decisions to confident that we could also overcome this latest spat. make. They shape their environment as much as they Now I just don’t know any more. After a series of are shaped by it. The right choices could help put the increasingly depressing trips to Europe, even my world’s main liberal democracies back in the same optimism is being tested. -

The Wilsonian Open Door and Truman's China-Taiwan Policy

Dean P. Chen American Association for Chinese Studies Annual Conference October 12-14, 2012 Origins of the Strategic Ambiguity Policy: The Wilsonian Open Door and Truman’s China-Taiwan Policy 1 The Problem of the Taiwan Strait Conflict The Taiwan Strait is probably one of the “most dangerous” flashpoints in world politics today because the Taiwan issue could realistically trigger an all-out war between two nuclear-armed great powers, the United States and People’s Republic of China (PRC). 2 Since 1949, cross-strait tensions, rooted in the Chinese civil war between Chiang Kai- shek’s Nationalist Party (KMT) and Mao Zedong’s Communist Party (CCP), have been contentious and, at times, highly militarized. As analyzed by many scholars, the Taiwan Strait crises in 1954, 1958, 1995-96, and 2003-06 brought the PRC, Taiwan, and the United States closely to the brink of war. 3 In each of these episodes, however, rational restraint prevailed due to America’s superior power influence to prevent both sides from upsetting the tenuous cross-strait status quo. Indeed, having an abiding interest in a peaceful resolution of the Taiwan Strait conflict, Washington has always assumed a pivotal role in deterring both Taipei and Beijing from aggressions and reckless behaviors. U.S. leaders seek to do this through the maintenance of a delicate balance: acknowledging the one-China principle, preserving the necessary ties to defend Taiwan’s freedom and security while insisting that all resolutions must be peaceful and consensual. 4 The Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter, and Ronald Reagan administrations formalized these commitments in the three U.S.-China 1 This paper is an abridged and modified version of the author’s recent book: Dean P. -

Changes from FDR to Dean Acheson

Department of History University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Modernization of the State Department: Changes from FDR to Dean Acheson 1945-1953 Kyle Schwan Cooperating Professor: Oscar Chamberlain 1 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………....4 Historiography……………………………………………………………………………5 The FDR Years and “Old State”……………………………………………………….6 Changes in the Post FDR Years………………………………………………………10 The Truman Acheson years……………………………………………………………13 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………..15 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………18 2 Abstract This capstone looks at and analyzes the changes in organization and administration of the United States Department of State from the middle of the 1940’s through 1953. Looking at the organization of the State Department during these years will show the influence World War II had on the Department as well as how the Department grew in order to manage all of the new areas of interest of the United States Government. Along with this it looks at the role that each Secretary of State played in making changes to the State Department especially the decisions and actions taken by Dean Acheson. Official State Department documents along with Congressional records are used as well as the personal accounts of various people including Dean Acheson. 3 Introduction As the United States was regrouping from World War II it needed to decide what to do with the massive war machine that had been created in order to be victorious. In many cases this war machine was dismantled and departments were disbanded. However, one department grew and grew exponentially due to the fact that the United States had been thrust into the front of world politics and world economics. This department was now required to oversee the entire world and assess any threats to itself and its allies. -

Liberalism, Communitarianism, and Asocialism in This Paper We Will Look

Andrew Jason Cohen, “Liberalism, Communitarianism, and Asocialism,” Pre-Publication Version Liberalism, Communitarianism, and Asocialism In this paper we will look at three versions of the charge that liberalism’s emphasis on individuals is detrimental to community—that it encourages a pernicious disregard of others by fostering a particular understanding of the individual and the relation she has with her society. According to that understanding, individuals are fundamentally independent entities who only enter into relations by choice and society is nothing more than a venture voluntarily entered into in order to better ourselves. Communitarian critics argue that since liberals neglect the degree to which individuals are dependent upon their society for their self-understanding and understanding of the good, they encourage individuals to maintain a personal distance from others in their society. The detrimental effect this distancing is said to have on communities is often called “asocial individualism” or “asocialism.” Jean Bethke Elshtain sums up this view: “Within a world of choice-making Robinson Crusoes, disconnected from essential ties with one another, any constraint on individual freedom is seen as a burden, most often an unacceptable one.”1 In the first three sections, we look at the first version of the charge that liberalism is detrimental to community. This concerns the “distancing” discussed above: the claim is that liberalism encourages individuals to opt out of relationships too readily. In the fourth section, we briefly discuss the second variant: that liberalism induces aggressive behavior. Finally, in sections five and six, we address the third version of the charge: liberalism does not provide for the social trust that is necessary for cooperation and the provision of communal goods. -

DEAN ACHESON and the MAKING of U.S. FOREIGN POLICY Also L7y Douglas Brinkley DEAN ACHESON: the COLD WAR YEARS 1953-1971 DRIVEN PATRIOT: the LIFE and TIMES of JAMES V

DEAN ACHESON AND THE MAKING OF U.S. FOREIGN POLICY Also l7y Douglas Brinkley DEAN ACHESON: THE COLD WAR YEARS 1953-1971 DRIVEN PATRIOT: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF JAMES V. FORRESTAL (with Townsend Hoopes) JEAN MONNET: THE PATH TO EUROPEAN UNITY (coedited with Clifford Hackett) Dean Acheson and the Making of U.S. Foreign Policy Edited by Douglas Brinkley Assistant Professor of History Hofstra University palgrave macmillan ©Douglas Brinkley 1993 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1993 978-0-333-56735-7 All rights reseiVed. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 9HE. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. First published 1993 by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 2XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 978-1-349-22613-9 ISBN 978-1-349-22611-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-22611-5 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

How the War Shaped the Man

Los Angeles Times February 22, 2004 Sunday BOOK REVIEW; Part R; Pg. 7 LENGTH: 1602 words How the War Shaped the Man Tour of Duty: John Kerry and the Vietnam War; Douglas Brinkley; William Morrow: 546 pp., $25.95 David J. Garrow, David J. Garrow is the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning "Bearing the Cross," a biography of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. John Kerry enlisted in the Navy four months before graduating from Yale University in 1966. With U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War escalating rapidly, joining voluntarily offered more attractive options to a young college graduate than did waiting to be drafted. After completing officer candidate school, 23-year-old Ensign Kerry was assigned to the guided- missile frigate U.S.S. Gridley, based in Long Beach. In early February 1968, a day after the Gridley set sail for Southeast Asia, Ensign Kerry requested reassignment as a small-boat commander in Vietnam. "I didn't really want to get involved in the war," Kerry said in 1986 during his first term in the U.S. Senate. "When I signed up for the swift boats, they had very little to do with the war. They were involved in coastal patrolling and that's what I thought I was going to be doing." Two weeks after that request, Kerry learned that one of his closest Yale friends, Richard Pershing, grandson of Gen. John "Black Jack" Pershing, had died in a Viet Cong ambush while serving as a lieutenant in the 101st Airborne. Pershing's death traumatized Kerry. -

James F. Byrnes' Yalta Rhetoric

Journal of Political Science Volume 10 Number 2 (Spring) Article 1 April 1983 James F. Byrnes' Yalta Rhetoric Bernard Duffy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Duffy, Bernard (1983) "James F. Byrnes' Yalta Rhetoric," Journal of Political Science: Vol. 10 : No. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops/vol10/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Politics at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Political Science by an authorized editor of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. James F. Byrnes' Yalta Rhetoric BERNARD K. DUFFY Clemson University James F. Byrnes, Roosevelt's "Assistant President for the home front," was annointed to international politics during the fateful Yalta Conference. Byrnes' experience prior to Yalta had been primarily as a domestic politician. His participation in the Yalta Conference identified him with matters of state beyond proportion to his actual experience and made him a credible candidate for Secretary of State in the Truman ad ministration. If Yalta was crucial to Byrnes' political career, it was equally important to the way Roosevelt was perceived during the Cold War years. Brynes' reputation and the memory of Franklin Roosevelt were both shaped by the South Carolinian's public statements about Yalta. Byrnes' initial pronouncements on Yalta came just one day after the in tentionally terse and ambiguous Yalta communique was issued by the Big Three. Roosevelt, who would not return from Yalta by ship until more than two weeks after the Conference closed, asked Byrnes to fly home first.