Problems of Perception in Diplomacy: the Decisions to Intervene in Korea and Vietnam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States of America Assassination

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ASSASSINATION RECORDS REVIEW BOARD *** PUBLIC HEARING Federal Building 1100 Commerce Room 7A23 Dallas, Texas Friday, November 18, 1994 The above-entitled proceedings commenced, pursuant to notice, at 10:00 a.m., John R. Tunheim, chairman, presiding. PRESENT FOR ASSASSINATION RECORDS REVIEW BOARD: JOHN R. TUNHEIM, Chairman HENRY F. GRAFF, Member KERMIT L. HALL, Member WILLIAM L. JOYCE, Member ANNA K. NELSON, Member DAVID G. MARWELL, Executive Director WITNESSES: JIM MARRS DAVID J. MURRAH ADELE E.U. EDISEN GARY MACK ROBERT VERNON THOMAS WILSON WALLACE MILAM BEVERLY OLIVER MASSEGEE STEVE OSBORN PHILIP TenBRINK JOHN McLAUGHLIN GARY L. AGUILAR HAL VERB THOMAS MEROS LAWRENCE SUTHERLAND JOSEPH BACKES MARTIN SHACKELFORD ROY SCHAEFFER 2 KENNETH SMITH 3 P R O C E E D I N G S [10:05 a.m.] CHAIRMAN TUNHEIM: Good morning everyone, and welcome everyone to this public hearing held today in Dallas by the Assassination Records Review Board. The Review Board is an independent Federal agency that was established by Congress for a very important purpose, to identify and secure all the materials and documentation regarding the assassination of President John Kennedy and its aftermath. The purpose is to provide to the American public a complete record of this national tragedy, a record that is fully accessible to anyone who wishes to go see it. The members of the Review Board, which is a part-time citizen panel, were nominated by President Clinton and confirmed by the United States Senate. I am John Tunheim, Chair of the Board, I am also the Chief Deputy Attorney General from Minnesota. -

The American Experience with Diplomacy and Military Restraint I

PART I: THE AmERICAN EXPERIENCE WITH DIPLOMACY AND MILITARY RESTRAINT i. Orphaned Diplomats: The American Struggle to Match Diplomacy with Power Jeremi Suri E. Gordon Fox Professor of History and Director, European Union Center of Excellence, University of Wisconsin, Madison Benjamin Franklin spent the American Revolution in Paris. He had helped to draft the Declaration of Independence in the summer of 1776, one of the most radical documents of the eighteenth century—sparking rebellion on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Serving as a representative for the Continental Congress in France during the next decade, Franklin became a celebrity. He was the enlightened idealist from the frontier, the man of principled action who enthralled onlookers in the rigid European class societies of the 1770s and ’80s. Franklin embodied the American critique of Old World society, economy, and diplomacy. He was one of many American revolutionaries to take aim at the degenerate world of powdered wigs, fancy uniforms, and silver-service dinners where the great men of Europe decided the fate of distant societies. Franklin was a representative of the enduring American urge to replace the diplomacy of aristocrats with the openness and freedom of democrats.1 Despite his radical criticisms of aristocracy, Franklin was also a prominent participant in Parisian salons. To the consternation of John Adams and John Jay, he dined most evenings with the most conservative elements of French high society. Unlike Adams, he did not refuse to dress the part. For all his frontiers- man claims, Franklin relished high-society silver-service meals, especially if generous portions of wine were available for the guests. -

Dean G. Acheson Oral History Interview – JFK #1, 4/27/1964 Administrative Information

Dean G. Acheson Oral History Interview – JFK #1, 4/27/1964 Administrative Information Creator: Dean G(ooderham) Acheson Interviewer: Lucius D. Battle Date of Interview: April 27, 1964 Place of Interview: Washington, D.C. Length: 34 pp. Biographical Note Acheson, Secretary of State under President Harry S. Truman, talks about foreign policy matters during the John F. Kennedy administration and his advice and activities during that time. He also reads the text of several letters he wrote to JFK. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed February 15, 1965, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. Direct your questions concerning copyright to the reference staff. Transcript of Oral History Interview These electronic documents were created from transcripts available in the research room of the John F. -

Exploring London

05 539175 Ch05.qxd 10/23/03 11:00 AM Page 105 5 Exploring London Dr. Samuel Johnson said, “When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life, for there is in London all that life can afford.” It would take a lifetime to explore every alley, court, street, and square in this city, and volumes to discuss them. Since you don’t have a lifetime to spend, we’ve chosen the best that London has to offer. For the first-time visitor, the question is never what to do, but what to do first. “The Top Attractions” section should help. A note about admission and open hours: In the listings below, children’s prices generally apply to those 16 and under. To qualify for a senior discount, you must be 60 or older. Students must present a student ID to get discounts, where available. In addition to closing on bank holidays, many attractions close around Christmas and New Year’s (and, in some cases, early in May), so always call ahead if you’re visiting in those seasons. All museums are closed Good Friday, from December 24 to December 26, and New Year’s Day. 1 The Top Attractions British Museum Set in scholarly Bloomsbury, this immense museum grew out of a private collection of manuscripts purchased in 1753 with the proceeds of a lottery. It grew and grew, fed by legacies, discoveries, and purchases, until it became one of the most comprehensive collections of art and artifacts in the world. It’s impossible to take in this museum in a day. -

{PDF EPUB} the Color of Truth Mcgeorge Bundy and William

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Color of Truth McGeorge Bundy and William Bundy Brothers in Arms by Kai Bird The Color of Truth: McGeorge Bundy and William Bundy: Brothers in Arms by Kai Bird. The Color of Truth: McGeorge Bundy and William Bundy-Brothers in Arms. Simon & Schuster, $27.50. When Telford Taylor, United States prosecutor at Nuremberg, returned from a trip to North Vietnam at the height of the US bombings there, he was asked on national television if, under international law, McGeorge Bundy could be judged guilty of war crimes. "Yes, of course," he replied. McGeorge "Mac" Bundy was a war criminal. So was his brother William. So I came to believe after a decade in the anti-Vietnam War movement. And nothing I read in Kai Bird's new biography of the Bundy brothers, The Color of Truth: McGeorge Bundy and William Bundy-Brothers in Arms , changes my opinion. Weaving a rich history of government documents-some recently declassified, some still classified-with interviews and a fresh look at available sources, Bird delivers the definitive assessment of two Cold Warriors. Neither Bundy topped the antiwar movement's enemies list. Those lofty perches were reserved for Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Robert McNamara, Henry Kissinger and William Westmoreland. Yet Mac Bundy, as Bird reminds us, "was a prime architect of the Vietnam War." And over their careers as intellectual bureaucrats, the moral compass of each Bundy was revealed to lack key points, especially when it came to using weapons of mass destruction in Asia. "Ultimately," Bird writes, "the Bundys were policy intellectuals shackled by Cold War shibboleths which they could not quite bear to break." David Dellinger, the pacifist leader of the antiwar movement, knew Mac Bundy in 1937, when they were classmates at Yale. -

Dean Rusk Oral History Collection Rusk H Dean Rusk Interviewed by Richard Rusk 1984 October 22

Dean Rusk Oral History Collection Rusk H Dean Rusk interviewed by Richard Rusk 1984 October 22 RICHARD RUSK: Interview with Dean Rusk on his boyhood days in Atlanta. A lot of these questions and material is based on Franklin [Miller] Garrett's book called Atlanta and Its Environs. What are your first memories of events in Atlanta, not necessarily your boyhood or childhood but the very first things you remember as far as the public events of Atlanta are concerned. DEAN RUSK: I think probably the coming of World War I, the fact that a number of my cousins went off to the service in the Army or the Navy. Of course, during the war we had that huge fire on the north side of town, destroyed about a third of the city. From where we lived we could clearly see that smoke and sense some of the excitement and confusion to that period. Rumors were going around that a German plane had been seen and dropped a bomb over the city to start the fire, which was nonsense of course. But I wasn't, as a small boy, caught up very much in the events of the city of Atlanta. That was fairly well removed from our lives out there in West End. But I think those were the two things that occurred while I was a small boy living there. RICHARD RUSK: The section, West End in Atlanta--just some general characteristics of West End. Again, a lot of this you have already given me. DEAN RUSK: In those days, West End was a very modest little community about two miles from downtown. -

Chapter I Geostrategic and Geopolitical Considerations

Geostrategic and geopolitical Chapter I considerations regarding energy Francisco José Berenguer Hernández Abstract This chapter analyses the peace and conflict aspects of the concept of “energy security” its importance in the strategic architecture of the major nations, as well as the main geopolitical factors of the current energy panorama. Key words Energy Security, National Strategies, Energy Interests, Geopolitics of Energy. 45 Francisco José Berenguer Hernández Some considerations about the “energy security” concept Concept The concept of energy security has been present in publications for a cer- tain number of years, including the press and non-trade media, but it is apparently a recent one, or at least one that has not enjoyed the popular- ity of others such as road, workplace, social or even air security. However, it has taken on such importance nowadays that it deserves a specific section in the highest-level strategic documents of practically all of the nations in our environment, as will be seen in a later section. This is somewhat different from the form of security of other sectors that include the following in more generic terms: “well-being and progress of society”, “ensuring the life and prosperity of citizens” and other simi- lar expressions, with the exception of economic security. The latter, as a consequence of the long and deep recession that numerous nations, in- cluding Spain, have been suffering, has strongly emerged in more recent strategic thinking. Consequently, it is worth wondering the reason for this relevance and leading role of energy security in the concerns of the high- est authorities and institutions of the nations. -

Philosophy Sunday, July 8, 2018 12:01 PM

Philosophy Sunday, July 8, 2018 12:01 PM Western Pre-Socratics Fanon Heraclitus- Greek 535-475 Bayle Panta rhei Marshall Mcluhan • "Everything flows" Roman Jakobson • "No man ever steps in the same river twice" Saussure • Doctrine of flux Butler Logos Harris • "Reason" or "Argument" • "All entities come to be in accordance with the Logos" Dike eris • "Strife is justice" • Oppositional process of dissolving and generating known as strife "The Obscure" and "The Weeping Philosopher" "The path up and down are one and the same" • Theory about unity of opposites • Bow and lyre Native of Ephesus "Follow the common" "Character is fate" "Lighting steers the universe" Neitzshce said he was "eternally right" for "declaring that Being was an empty illusion" and embracing "becoming" Subject of Heideggar and Eugen Fink's lecture Fire was the origin of everything Influenced the Stoics Protagoras- Greek 490-420 BCE Most influential of the Sophists • Derided by Plato and Socrates for being mere rhetoricians "Man is the measure of all things" • Found many things to be unknowable • What is true for one person is not for another Could "make the worse case better" • Focused on persuasiveness of an argument Names a Socratic dialogue about whether virtue can be taught Pythagoras of Samos- Greek 570-495 BCE Metempsychosis • "Transmigration of souls" • Every soul is immortal and upon death enters a new body Pythagorean Theorem Pythagorean Tuning • System of musical tuning where frequency rations are on intervals based on ration 3:2 • "Pure" perfect fifth • Inspired -

Table of Contents

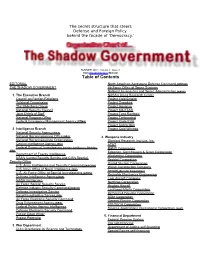

The secret structure that steers Defense and Foreign Policy behind the facade of 'Democracy.' SUMMER 2001 - Volume 1, Issue 3 from TrueDemocracy Website Table of Contents EDITORIAL North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) THE SHADOW GOVERNMENT Air Force Office of Space Systems National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) 1. The Executive Branch NASA's Ames Research Center Council on Foreign Relations Project Cold Empire Trilateral Commission Project Snowbird The Bilderberg Group Project Aquarius National Security Council Project MILSTAR Joint Chiefs of Staff Project Tacit Rainbow National Program Office Project Timberwind Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Project Code EVA Project Cobra Mist 2. Intelligence Branch Project Cold Witness National Security Agency (NSA) National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) 4. Weapons Industry National Reconnaissance Organization Stanford Research Institute, Inc. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) AT&T Federal Bureau of Investigation , Counter Intelligence Division RAND Corporation (FBI) Edgerton, Germhausen & Greer Corporation Department of Energy Intelligence Wackenhut Corporation NSA's Central Security Service and CIA's Special Bechtel Corporation Security Office United Nuclear Corporation U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) Walsh Construction Company U.S. Navy Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) Aerojet (Genstar Corporation) U.S. Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI) Reynolds Electronics Engineering Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) Lear Aircraft Company NASA Intelligence Northrop Corporation Air Force Special Security Service Hughes Aircraft Defense Industry Security Command (DISCO) Lockheed-Maritn Corporation Defense Investigative Service McDonnell-Douglas Corporation Naval Investigative Service (NIS) BDM Corporation Air Force Electronic Security Command General Electric Corporation Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) PSI-TECH Corporation Federal Police Agency Intelligence Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) Defense Electronic Security Command Project Deep Water 5. -

Eisenhower, Dwight D.: Post-Presidential Papers, 1961-69

EISENHOWER, DWIGHT D.: POST-PRESIDENTIAL PAPERS, 1961-69 1961 PRINCIPAL FILE Series Description Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Post-Presidential Papers reveal the wide range of contacts and the busy schedule which he maintained during the 1960s. A large volume of mail kept his small secretarial staff busy, and he was in great demand as a public speaker. Correspondence in the Post-Presidential Papers offers some interesting insights into Eisenhower’s thinking on numerous issues. No longer burdened by the responsibilities of public office, he felt freer, perhaps, to express himself on various topics. Among the issues discussed in documents found within the 1961 Principal File are the space program, the Berlin situation, Republican party politics, the U.S. economy and monetary policy, and the 1960 elections. Additional topics discussed include Cuba and the Bay of Pigs disaster, foreign aid, taxes, the alleged missile gap, the 1952 campaign, the U.S.I.A.’s mission, the Electoral College, Laos, Latin America, and public housing. Eisenhower’s correspondence in the 1961 Principal File reflects a virtual Who’s Who of both foreign leaders and prominent Americans. Konrad Adenauer of Germany, John Diefenbaker of Canada, Anthony Eden, Harold Macmillan, and Queen Elizabeth of Great Britain, Prime Minister Menzies of Australia, President Mateos of Mexico, and King Saud of Saudi Arabia are among the foreign leaders who stayed in touch with the ex-president. Many prominent Americans maintained contact with the former president as well. He corresponded with numerous former members of his administration, including Dillon Anderson, Ezra Taft Benson, Arthur F. Burns, Andrew Goodpaster, James Hagerty, Bryce Harlow, Gabriel Hauge, C.D. -

Sipanews Winter 2000 / VOLUME Xiii NO.1 1 from the Dean Lisa Anderson Takes Stock of SIPA in the New Millenium

SIPAnews winter 2000 / VOLUME XIiI NO.1 1 From the Dean Lisa Anderson takes stock of SIPA in the new millenium. 2 Economist Robert Mundell is Columbias latest Nobel Prize winner. 3 Professor Kathleen Molz takes a critical look at Internet filters. 4 Dear SIPA 99 grad Jun Choi tells us about life on the campaign trail. 5 Alumni Profile: John Neuffer Cold pizza leads to 15 minutes of fame for SIPA grad. 6 Alumni Forum: Cecelia Caruso Alumna fights for textbooks for New York children of color. 8 Executive MPA Program makes SIPA debut. 7 Schoolwide News 10 13 MPA Program News Six SIPA students bring love and laughter to Kosovo refugees. 14 MIA Program News 15 Urban Affairs 12 17 Faculty News SIPA student groups offer something for everyone. 20 Staff News 21 Class Notes SIPA news 1 Our more recent alumni- should we call you the ele- vator classes?-continue to remember the faculty as having a profound impact on their lives and careers. From the Dean: Lisa Anderson Raise a Glass to SIPA As Clock Strikes Midnight ebrate them. We and the economics energy and other resources to conduct department bask in the reflected glory their own research and policy analysis. of Professor Robert Mundells Nobel We at SIPA have enjoyed and profited Prize, of course, but also enjoy the from their dedication to teaching and honors and awards a number of other to strengthening our institution, and at faculty are collecting, including long last we are in a position to recip- Robert Liebermans Trilling Prize for rocate what they have done for us. -

Rethinking Atomic Diplomacy and the Origins of the Cold War

Journal of Political Science Volume 29 Number 1 Article 5 November 2001 Rethinking Atomic Diplomacy and the Origins of the Cold War Gregory Paul Domin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Domin, Gregory Paul (2001) "Rethinking Atomic Diplomacy and the Origins of the Cold War," Journal of Political Science: Vol. 29 : No. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops/vol29/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Politics at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Political Science by an authorized editor of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rethinking Atomic Diplomacy and the Origins of the Cold War Gregory Paul Domin Mercer University This paper argues that the conflict between nuclear na tionalist and nuclear internationalist discourses over atomic weapons policy was critical in the articulation of a new system of American power . The creation of the atomic bomb destroyed the Roosevelt's vision of a post war world order while confronting United States (and Soviet) policymakers with alternatives that, before the bomb's use, only a handful of individuals had contem plated. The bomb remade the world . My argument is that the atomic bomb did not cause the Cold War, but without it, the Cold War could not have occurred . INTRODUCTION he creation of the atomic bomb destroyed the Roose veltian vision of a postwar world order while confronting TUnited States (and Soviet) policymakers with a new set of alternatives that, prior to the bomb's use, only a bare handful of individuals among those privy to the secret of the Manhattan Project had even contemplated.