A Return Ticket for the Shetland Bus? Scottish-Swedish Air Connections During the Second World War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Introduction

Notes 1 Introduction 1. Donald Macintyre, Narvik (London: Evans, 1959), p. 15. 2. See Olav Riste, The Neutral Ally: Norway’s Relations with Belligerent Powers in the First World War (London: Allen and Unwin, 1965). 3. Reflections of the C-in-C Navy on the Outbreak of War, 3 September 1939, The Fuehrer Conferences on Naval Affairs, 1939–45 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1990), pp. 37–38. 4. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 10 October 1939, in ibid. p. 47. 5. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 8 December 1939, Minutes of a Conference with Herr Hauglin and Herr Quisling on 11 December 1939 and Report of the C-in-C Navy, 12 December 1939 in ibid. pp. 63–67. 6. MGFA, Nichols Bohemia, n 172/14, H. W. Schmidt to Admiral Bohemia, 31 January 1955 cited by Francois Kersaudy, Norway, 1940 (London: Arrow, 1990), p. 42. 7. See Andrew Lambert, ‘Seapower 1939–40: Churchill and the Strategic Origins of the Battle of the Atlantic, Journal of Strategic Studies, vol. 17, no. 1 (1994), pp. 86–108. 8. For the importance of Swedish iron ore see Thomas Munch-Petersen, The Strategy of Phoney War (Stockholm: Militärhistoriska Förlaget, 1981). 9. Churchill, The Second World War, I, p. 463. 10. See Richard Wiggan, Hunt the Altmark (London: Hale, 1982). 11. TMI, Tome XV, Déposition de l’amiral Raeder, 17 May 1946 cited by Kersaudy, p. 44. 12. Kersaudy, p. 81. 13. Johannes Andenæs, Olav Riste and Magne Skodvin, Norway and the Second World War (Oslo: Aschehoug, 1966), p. -

No. 16673 SWEDEN and IRAN Air Transport Agreement

No. 16673 SWEDEN and IRAN Air Transport Agreement (with annex and related note). Signed at Tehran on 10 June 1975 Authentic texts of the Agreement and annex: Swedish, Persian and English. Authentic text of the related note: English. Registered by the International Civil Aviation Organization on 5 May 1978. SUÈDE et IRAN Accord relatif aux transports aériens (avec annexe et note connexe). Signé à Téhéran le 10 juin 1975 Textes authentiques de l©Accord et de l©annexe : su dois, persan et anglais. Texte authentique de la note connexe : anglais. Enregistr par l©Organisation de l©aviation civile internationale le 5 mai 1978. Vol. 1088,1-16673 1978_____United Nations — Treaty Series • Nations Unies — Recueil des Traités_____283 AIR TRANSPORT AGREEMENT1 BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE KINGDOM OF SWEDEN AND THE IMPERIAL GOVERN MENT OF IRAN The Government of the Kingdom of Sweden and the Imperial Government of Iran, Being equally desirous to conclude an Agreement for the purpose of establishing and operating commercial air services between and beyond their respective terri tories, have agreed as follows: Article 1. DEFINITIONS For the purpose of the present Agreement, unless the context otherwise requires: à) The term "aeronautical authorities" means, in the case of Iran, the Depart ment General of Civil Aviation, and any person or body authorized to perform any functions at present exercised by the said Department General or similar functions, and, in the case of Sweden, the Board of Civil Aviation, and any person or body authorized to perform any functions at present exercised by the said Board or similar functions. -

The Impact of External Shocks Upon a Peripheral Economy: War and Oil in Twentieth Century Shetland. Barbara Ann Black Thesis

THE IMPACT OF EXTERNAL SHOCKS UPON A PERIPHERAL ECONOMY: WAR AND OIL IN TWENTIETH CENTURY SHETLAND. BARBARA ANN BLACK THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL HISTORY July 1995 ProQuest Number: 11007964 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11007964 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis, within the context of the impact of external shocks on a peripheral economy, offers a soci- economic analysis of the effects of both World Wars and North Sea oil upon Shetland. The assumption is, especially amongst commentators of oil, that the impact of external shocks upon a peripheral economy will be disruptive of equilibrium, setting in motion changes which would otherwise not have occurred. By questioning the classic core-periphery debate, and re-assessing the position of Shetland - an island location labelled 'peripheral' because of the traditional nature of its economic base and distance from the main centres of industrial production - it is possible to challenge this supposition. -

Norwegian PPT. Programs Available for SON Groups

Norwegian PPT. Programs Available For SON Groups Programs that are offered to any SON lodge, for $50, plus travel/gas money. Presented by: Arno Morton Phone: 715-341-7248 (Home) E-Mail: [email protected] 715-570-9002 (Cell) 1. Norwegian Double Agent – WW2 ***** This is the story of one young Norwegian farmer, who in the summer of 1940, shortly after the German occupation, became a Double Agent against the Nazis to help the British SIS and the Norwegian Resistance in his home town of Flekkefjord, Norway. This true story of Gunvald Tomstad explains how this young Pacifist joined the Nazi Party and became an outcast in his own community so that he might be a Double Agent for his beloved Norway! (Approx. 45 Min.) 2. The German Invasion of Norway in WW2 ***** This presentation begins with the Altmark Incident in February 16, 1940, and is followed by the April 9, 1940 invasion of neutral Norway, explaining the proposed reasons for the German invasion, and the subsequent conditions that prevailed. Norwegian atrocities, the Norwegian resistance and Heroes, the hiding of Norway’s gold reserves, and escape of Norway’s King are all covered. Other more controversial topics are also touched on in this stirring and comprehensive tribute to the tenacity of the Norwegian people. (Approx. 1 Hr. 10 min.) 3. Being a Viking ***** This presentation takes you back to the early years of Viking history, explaining the pre-Christianity Viking mindset, the Viking homestead, Viking foods, the Viking Warrior, the Viking raids, the Viking longships, the need for Viking expansion, and Viking explorations. -

Air Transport

The History of Air Transport KOSTAS IATROU Dedicated to my wife Evgenia and my sons George and Yianni Copyright © 2020: Kostas Iatrou First Edition: July 2020 Published by: Hermes – Air Transport Organisation Graphic Design – Layout: Sophia Darviris Material (either in whole or in part) from this publication may not be published, photocopied, rewritten, transferred through any electronical or other means, without prior permission by the publisher. Preface ommercial aviation recently celebrated its first centennial. Over the more than 100 years since the first Ctake off, aviation has witnessed challenges and changes that have made it a critical component of mod- ern societies. Most importantly, air transport brings humans closer together, promoting peace and harmo- ny through connectivity and social exchange. A key role for Hermes Air Transport Organisation is to contribute to the development, progress and promo- tion of air transport at the global level. This would not be possible without knowing the history and evolu- tion of the industry. Once a luxury service, affordable to only a few, aviation has evolved to become accessible to billions of peo- ple. But how did this evolution occur? This book provides an updated timeline of the key moments of air transport. It is based on the first aviation history book Hermes published in 2014 in partnership with ICAO, ACI, CANSO & IATA. I would like to express my appreciation to Professor Martin Dresner, Chair of the Hermes Report Committee, for his important role in editing the contents of the book. I would also like to thank Hermes members and partners who have helped to make Hermes a key organisa- tion in the air transport field. -

National Gallery of Art Fall10 Film Washington, DC Landover, MD 20785

4th Street and Mailing address: Pennsylvania Avenue NW 2000B South Club Drive NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART FALL10 FILM Washington, DC Landover, MD 20785 FIGURES IN A STRAUB AND LANDSCAPE: JULIEN HUILLET: THE NATURE AND DUVIVIER: WORK AND HARUN NARRATIVE THE GRAND REACHES OF FAROCKI: IN NORWAY ARTISAN CREATION ESSAYS When Angels Fall Manhattan cover calendar page calendar (Harun Farocki), page four page three page two page one Still of performance duo ZsaZa (Karolina Karwan) When Angels Fall (Henryk Kucharski) A Tale of HarvestA Tale The Last Command (Photofest), Force of Evil Details from FALL10 Images of the World and the Inscription of War (Henryk Kucharski), (Photofest) La Bandera (Norwegian Institute) Film Images of the (Photofest) (Photofest) Force of Evil World and the Inscription of War (Photofest), Tales of (Harun Farocki), Iris Barry and American Modernism Andrew Simpson on piano Sunday November 7 at 4:00 Art Films and Events Barry, founder of the film department at the Museum of Modern Art , was instrumental in first focusing the attention of American audiences on film as an art form. Born in Britain, she was also one of the first female film critics David Hockney: A Bigger Picture and a founder of the London Film Society. This program, part of the Gallery’s Washington premiere American Modernism symposium, re-creates one of the events that Barry Director Bruno Wollheim in person staged at the Wadsworth Athenaeum in Hartford in the 1930s. The program Saturday October 2 at 2:00 includes avant-garde shorts by Walter Ruttmann, Ivor Montagu, Viking Eggeling, Hans Richter, Charles Sheeler, and a Silly Symphony by Walt Disney. -

The Flyer – 2015 September

SONS OF NORWAY BERNT BALCHEN LODGE – PRESIDENT’S MEssAGE Steinar Hansen: An Exemplary Norwegian-American I would like to devote my message this month to the recognition of one of our own, Steinar Hansen. Steinar is the last person in Bernt Balchen Lodge who would seek recognition, but he deserves it, nevertheless. So, here it comes. Steinar Hansen was unanimously nominated VIKING HALL 349-1613 for a Bridge Builders of Anchorage Excellence www.sofnalaska.com in Community Service Award by at the June 11, 2015 Board/Membership Meeting of Sons of Norway Bernt Balchen Lodge. He now joins Marit Kristiansen and Eva Bilet, who are also recipients September of Bridge Builders Excellence in Community Service Awards (2013 and 2014). Steinar received his award at the Bridge Builders Unity Gala on 2015 August 22, 2015 at the Marriott Hotel in front of over 400 guests and other honorees including First september Lady Donna Walker, a vocal supporter of Bridge Steinar Hansen flanked on the left by his son Builders. Bjarne Hansen and his wife Jacqueline, and on the right by his daughter Anita Persson and her The mission of Bridge Builders is to build “a husband Lloyd Persson. community of friends” among all racial and cultural groups in Anchorage. The specific purpose of the Bridge Builders Unity Gala is to honor those who have made significant contributions in their respective ethnic communities. Steinar Hansen was born in Lillehammer, in eastern Norway in 1933. As a child he moved to western Norway and grew up in a small town near the city of Alesund. -

Mo Birget Soađis (How to Cope with War) – Strategies of Sámi Resilience During the German Influence

Mo birget soađis (How to cope with war) – strategies of Sámi resilience during the German influence Adaptation and resistance in Sámi relations to Germans in wartime Sápmi, Norway and Finland 1940-1944 Abstract The article studies the Sámi experiences during the “German era” in Norway and Finland, 1940-44, before the Lapland War. The Germans ruled as occupiers in Norway, but had no jurisdiction over the civilians in Finland, their brothers-in-arms. In general, however, encounters between the local people and the Germans appear to have been cordial in both countries. Concerning the role of racial ideology, it seems that the Norwegian Nazis had more negative opinions of the Sámi than the occupiers, while in Finland the racial issues were not discussed. The German forces demonstrated respect for the reindeer herders as communicators of important knowledge concerning survival in the arctic. The herders also possessed valuable meat reserves. Contrary to this, other Sámi groups, such as the Sea Sámi in Norway, were ignored by the Germans resulting in a forceful exploitation of sea fishing. Through the North Sámi concept birget (coping with) we analyse how the Sámi both resisted and adapted to the situation. The cross-border area of Norway and Sweden is described in the article as an exceptional arena for transnational reindeer herding, but also for the resistance movement between an occupied and a neutral state. Keyword: Sámi, WWII, Norway and Finland, reindeer husbandry, local meetings, Birget Sámi in different wartime contexts In 1940 the German forces occupied Norway. Next year, as brothers-in-arms, they got northern Finland under their military command in order to attack Soviet Union. -

Innehåll R E

S A S k o n c e r n e n s Å r s Innehåll r e d Affärsområde o 2 SAS koncernen v i 57 Hotels s Årets resultat 2 n Översikt, resultat och sammandrag 57 i SAS koncernen - styrmodell, styrfilosofi och nyckeltal 3 n g Översikt affärsområden 4 Varumärken, partners och hotellutveckling 59 & VD har ordet 6 Marknadsutsikter 60 H å Viktiga händelser 8 l l b a Kommersiell offensiv 9 r h Affärsidé, vision, mål & värderingar 10 e t s SAS koncernens strategier 11 61 Ekonomisk redovisning r e Turnaround 2005 13 d Förvaltningsberättelse 61 o Marknader & konkurrentanalys 15 v SAS koncernen i s Värde & tillväxt 16 n - Resultaträkning, inkl. kommentarer 66 i n På kundens villkor 18 - Resultat i sammandrag 67 g 2 Allianssamarbete 20 - Balansräkning, inkl. kommentarer 68 0 Kvalitet & säkerhet 22 0 - Förändring i eget kapital 69 4 - Kassaflödesanalys, inkl. kommentarer 70 23 Kapitalmarknaden - Redovisnings- och värderingsprinciper 71 Aktien 24 - Noter/tilläggsupplysningar 74 Ekonomisk tioårsöversikt inkl. kommentarer 26 SAS AB, moderbolaget, resultat- och balansräkning, Avkastningskrav & resultatkrav 28 kassaflödesanalys, förändring i eget kapital samt noter 88 Risker & känslighet 29 Förslag till vinstdisposition och Revisionsberättelse 90 Investeringar & kapitalbindning 31 Affärsområde 33 Scandinavian Airlines Businesses Scandinavian Airlines Danmark 36 91 Corporate Governance SAS Braathens 37 Ordföranden har ordet 94 Scandinavian Airlines Sverige 38 Styrelse & revisorer 95 Scandinavian Airlines International 39 SAS koncernens organisationsstruktur & legal struktur 96 Operationella nyckeltal - tioårsöversikt 40 Koncernledning 97 Historisk återblick 98 Affärsområde 41 Subsidiary & Affiliated Airlines På kundens Spanair 43 Widerøe 45 99 Hållbarhetsredovisning Blue1 46 SAS koncernens Hållbarhetsredovisning 2004 har villkor Business Economy Flex Economy airBaltic 47 granskats av koncernens externa revisorer. -

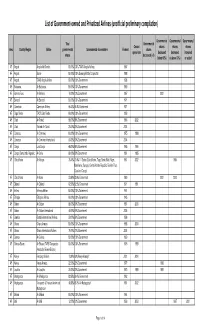

List of Government-Owned and Privatized Airlines (Unofficial Preliminary Compilation)

List of Government-owned and Privatized Airlines (unofficial preliminary compilation) Governmental Governmental Governmental Total Governmental Ceased shares shares shares Area Country/Region Airline governmental Governmental shareholders Formed shares operations decreased decreased increased shares decreased (=0) (below 50%) (=/above 50%) or added AF Angola Angola Air Charter 100.00% 100% TAAG Angola Airlines 1987 AF Angola Sonair 100.00% 100% Sonangol State Corporation 1998 AF Angola TAAG Angola Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1938 AF Botswana Air Botswana 100.00% 100% Government 1969 AF Burkina Faso Air Burkina 10.00% 10% Government 1967 2001 AF Burundi Air Burundi 100.00% 100% Government 1971 AF Cameroon Cameroon Airlines 96.43% 96.4% Government 1971 AF Cape Verde TACV Cabo Verde 100.00% 100% Government 1958 AF Chad Air Tchad 98.00% 98% Government 1966 2002 AF Chad Toumai Air Tchad 25.00% 25% Government 2004 AF Comoros Air Comores 100.00% 100% Government 1975 1998 AF Comoros Air Comores International 60.00% 60% Government 2004 AF Congo Lina Congo 66.00% 66% Government 1965 1999 AF Congo, Democratic Republic Air Zaire 80.00% 80% Government 1961 1995 AF Cofôte d'Ivoire Air Afrique 70.40% 70.4% 11 States (Cote d'Ivoire, Togo, Benin, Mali, Niger, 1961 2002 1994 Mauritania, Senegal, Central African Republic, Burkino Faso, Chad and Congo) AF Côte d'Ivoire Air Ivoire 23.60% 23.6% Government 1960 2001 2000 AF Djibouti Air Djibouti 62.50% 62.5% Government 1971 1991 AF Eritrea Eritrean Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1991 AF Ethiopia Ethiopian -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 I I I I 75-26,610

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

PROTOCOL at the Moment of Signing the Agreement Between the Government of the People's Republic of China and the Government Of

PROTOCOL At the moment of signing the Agreement between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Kingdom of Sweden for the Avoidance of Double Taxation and the Prevention of Fiscal Evasion with respect to Taxes on Income, the undersigned have agreed that the following provisions shall form an intergral part of the Agreement. To Articles 8 and 13 1. The provisions of Article 9 of the Agreement on Maritime Transport between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of Sweden signed at Beijing on the 18th of January 1975 shall not be affected by the Agreement. 2. When applying the Agreement the air transport consortium Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS) shall be regarded as having its head office in Sweden but the provisions of paragraph 1 of Article 8 and paragraph 3 of Article 13 shall apply only to that part of its profits as corresponds to the participation held in that consortium by AB Aerotransport (ABA), the Swedish partner of Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS) . To Article 12 For purposes of paragraph 3 of Article 12 it is understood that, in the case of payments received as a consideration for the use of or the right to use industrial, commercial or scientific equipment, the tax shall be imposed on 70 per cent of the gross amount of such payments. To Article 15 It is understood that where a resident of Sweden derives remuneration in respect of an employment exercised aboard an aircraft operated in international traffic by the air transport consortium Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS) such remuneration shall be taxable only in Sweden.