Life and Times of Alexander I., Emperor of All the Russias

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NAPOLEON's INVASION of RUSSIA ) "SPECIAL CAMPAIGN" SERIES with NUMEROUS MAPS and PLANS

a? s •X& m pjasitvcixxTA • &w* ^fffj President White Library , Cornell University Cornell University Library DC 235.B97 Napolean's invasion of Russia 3 1924 024 323 382 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924024323382 SPECIAL CAMPAIGN SERIES. No. 19 NAPOLEON'S INVASION OF RUSSIA ) "SPECIAL CAMPAIGN" SERIES With NUMEROUS MAPS and PLANS. Crown 8vo. Cloth. SI- net each (1) FROM SAARBRUCK TO PARIS (Franco-German War, 1870) By Lieut-Colonel SISSON PRATT, late R.A. (2) THE RUSSO-TURKISH WAR, 1877 By Major F. MAURICE, p.s.c. (3) FREDERICKSBURG CAMPAIGN, 1862 By Major Q. W. REDWAY (4) THE CAMPAIGN OF MAGENTA AND SOLFERINO, 1859 By Colonel HAROLD WYLLY, C.B. (5) THE WATERLOO CAMPAIGN By Lieut-Colonel SISSON PRATT, late R.A. (6) THE CAMPAIGN IN BOHEMIA, 1866 By Lieut-Colonel GLUNICKE (7) THE LEIPZIG CAMPAIGN, 1813 By Colonel F. N. MAUDE, C.B. (8) GRANT'S CAMPAIGN IN VIRGINIA (The Wilderness Campaign) By Captain VAUGHAN-SAWYER (9) THE JENA CAMPAIGN, 1806 By Colonel F. N. MAUDE, C.B. (10) THE RUSSO-JAPANESE WAR. Part I By Captain F. R. SEDGWICK (11) THE WAR OF SECESSION, 1861=2 (Bull Run to Malvern Hill By Major G. W. REDWAY (12) THE ULM CAMPAIGN, 1805 By Colonel F. N. MAUDE, C.B. (13) CHANCELLORSVILLE AND GETTYSBURG, 1863 By Colonel P. H. DALBIAC, C.B. (14) THE WAR OF SECESSION, 1863 (Cedar Run. Manassas and Sharpsburg)' By E. -

Napoleonic Army Summaries for Grand Battles Napoleon, 1808-1815

EMPIRE TO LIBERATION GENERIC NAPOLEONIC ARMY SUMMARIES FOR GRAND BATTLES NAPOLEON, 1808-1815 HEADQUARTERS OVERALL COMANDING GENERAL’S INITIATIVE RATING INITIATIVE ARMY POINTS RATING 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 Class -1 (Poor) -15 -15 -15 -15 -15 -15 Class 0 (Average) 5 10 15 20 25 30 Class 1 (Experienced) 15 30 45 60 75 90 Class 2 (Good) 35 70 105 140 175 210 Class 3 (Excellent) 50 100 150 200 300 405 CORPS COMMANDER LEADERSHIP RATING COMMAND RANGE POINTS RESPONSE Poor 8” 20cm -5 6+ Average 10” 25cm 5 5+ Experienced 12” 30cm 10 4+ Good 14” 35cm 15 3+ Excellent 16” 40cm 25 2+ DIVISIONAL COMMANDER LEADERSHIP RATING COMMAND RANGE POINTS RESPONSE Poor 2” 5cm -15 6+ Average 3” 7.5cm 0 5+ Experienced 4” 10cm 5 4+ Good 5” 12.5cm 10 3+ Excellent 6” 15cm 15 2+ CHARISMA NAME ARMY WING CORPS DIVISION Charismatic 40 40 40 N/A Superior N/A N/A N/A 40 Lucky 10 10 10 10 Unlucky -10 -10 -10 -10 SCREENS NAME POINTS French, British, Prussian, Italian, Polish and USA may have 0-2 screens per infantry regiment 5 All other infantry and cavalry regiments may have 0-1 screen pre regiment 5 NATIONAL LISTS AUSTRIA NAME SIZE MORALE NOTES MAX POINTS Grenz 8 5 Skirmish Light Infantry, 17 20 Jager 8 6 Skirmish Light Infantry, 12 35 Rifles Line 32 5 Napoleonic 64 50 Grenadier 16 7 Napoleonic, Exploit 10 50 Uhlans 12 5 Light Cavalry, Lancers 4 55 Chevauleger 12 6 Light Cavalry 7 60 Hussars 12 6 Light Cavalry 7 60 Dragoons 8 6 Medium Cavalry 6 55 Cuirassier 8 7 Heavy Cavalry, Exploit 8 80 6# Foot 2 6 Medium, Trained -/- 30 6# Horse 2 6 Medium Horse, Trained 16 40 -

Foreign Visitors and the Post-Stalin Soviet State

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2016 Porous Empire: Foreign Visitors And The Post-Stalin Soviet State Alex Hazanov Hazanov University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Hazanov, Alex Hazanov, "Porous Empire: Foreign Visitors And The Post-Stalin Soviet State" (2016). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2330. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2330 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2330 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Porous Empire: Foreign Visitors And The Post-Stalin Soviet State Abstract “Porous Empire” is a study of the relationship between Soviet institutions, Soviet society and the millions of foreigners who visited the USSR between the mid-1950s and the mid-1980s. “Porous Empire” traces how Soviet economic, propaganda, and state security institutions, all shaped during the isolationist Stalin period, struggled to accommodate their practices to millions of visitors with material expectations and assumed legal rights radically unlike those of Soviet citizens. While much recent Soviet historiography focuses on the ways in which the post-Stalin opening to the outside world led to the erosion of official Soviet ideology, I argue that ideological attitudes inherited from the Stalin era structured institutional responses to a growing foreign presence in Soviet life. Therefore, while Soviet institutions had to accommodate their economic practices to the growing numbers of tourists and other visitors inside the Soviet borders and were forced to concede the existence of contact zones between foreigners and Soviet citizens that loosened some of the absolute sovereignty claims of the Soviet party-statem, they remained loyal to visions of Soviet economic independence, committed to fighting the cultural Cold War, and profoundly suspicious of the outside world. -

OSW Report | Opposites Put Together. Belarus's Politics of Memory

OPPOSITES PUT TOGETHER BELARUS’S POLITICS OF MEMORY Kamil Kłysiński, Wojciech Konończuk WARSAW OCTOBER 2020 OPPOSITES PUT TOGETHER BELARUS’S POLITICS OF MEMORY Kamil Kłysiński, Wojciech Konończuk © Copyright by Centre for Eastern Studies CONTENT EDITOR Adam Eberhardt EDITOR Szymon Sztyk CO-OPERATION Tomasz Strzelczyk, Katarzyna Kazimierska TRANSLATION Ilona Duchnowicz CO-OPERATION Timothy Harrell GRAPHIC DESIGN PARA-BUCH DTP IMAGINI PHOTOGRAPH ON COVER Jimmy Tudeschi / Shutterstock.com Centre for Eastern Studies ul. Koszykowa 6a, 00-564 Warsaw, Poland tel.: (+48) 22 525 80 00, [email protected] www.osw.waw.pl ISBN 978-83-65827-56-2 Contents MAIN POINTS | 5 INTRODUCTION | 11 I. THE BACKGROUND OF THE BELARUSIAN POLITICS OF MEMORY | 14 II. THE SEARCH FOR ITS OWN WAY. ATTEMPTS TO DEFINE HISTORICAL IDENTITY (1991–1994) | 18 III. THE PRO-RUSSIAN DRIFT. THE IDEOLOGISATION OF THE POLITICS OF MEMORY (1994–2014) | 22 IV. CREATING ELEMENTS OF DISTINCTNESS. A CAUTIOUS TURN IN MEMORY POLITICS (2014–) | 27 1. The cradle of statehood: the Principality of Polotsk | 28 2. The powerful heritage: the Grand Duchy of Lithuania | 32 3. Moderate scepticism: Belarus in the Russian Empire | 39 4. A conditional acceptance: the Belarusian People’s Republic | 47 5. The neo-Soviet narrative: Belarusian territories in the Second Polish Republic | 50 6. Respect with some reservations: Belarus in the Soviet Union | 55 V. CONCLUSION. THE POLICY OF BRINGING OPPOSITES TOGETHER | 66 MAIN POINTS • Immediately after 1991, the activity of nationalist circles in Belarus led to a change in the Soviet historical narrative, which used to be the only permit ted one. However, they did not manage to develop a coherent and effective politics of memory or to subsequently put this new message across to the public. -

Making Jews Modern in the Polish Borderlands

Out of the Shtetl Making Jews Modern in the Polish Borderlands NANCY SINKOFF OUT OF THE SHTETL Program in Judaic Studies Brown University Box 1826 Providence, RI 02912 BROWN JUDAIC STUDIES Series Editors David C. Jacobson Ross S. Kraemer Saul M. Olyan Number 336 OUT OF THE SHTETL Making Jews Modern in the Polish Borderlands by Nancy Sinkoff OUT OF THE SHTETL Making Jews Modern in the Polish Borderlands Nancy Sinkoff Brown Judaic Studies Providence Copyright © 2020 by Brown University Library of Congress Control Number: 2019953799 Publication assistance from the Koret Foundation is gratefully acknowledged. Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non- Commercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecom- mons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. To use this book, or parts of this book, in any way not covered by the license, please contact Brown Judaic Studies, Brown University, Box 1826, Providence, RI 02912. In memory of my mother Alice B. Sinkoff (April 23, 1930 – February 6, 1997) and my father Marvin W. Sinkoff (October 22, 1926 – July 19, 2002) CONTENTS Acknowledgments....................................................................................... ix A Word about Place Names ....................................................................... xiii List of Maps and Illustrations .................................................................... xv Introduction: -

IBP7*717771Ttitl Secretary of the Air Force Edward C

^ y.i / m ] -1 /AJ f A f J IBP7*717771TTiTl Secretary of the Air Force Edward C. Aldridge, Jr. Air Force Chief of Staff Gen Larry D. Welch Commander, Air University Lt Gen Truman Spangrud Commander, Center for Aerospace Doctrine, Research, and Education Col Sidney J. Wise Professional Staff Editor Col Keith W. Geiger Associate Editor Maj Michael A. Kirtland Contributing Personnel Hugh Richardson, Associate Editor John A. Westcott, Art Director and Production Manager The Airpower Journal, published quarterly, is the professional journal of the United States Air Force. It is designed to serve as an open forum for presenting and stimulating innovative thinking on m ilitary doctrine, strategy, tactics, force struc- ture, readiness, and other national defense mat- ters. The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, the Air Force, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. Articles in this edition may be reproduced in whole or in part without permis- sion. If reproduced, the Airpower Journal re- quests a courtesy line. Editorial— Blinders, Too, Are Made of Leather 2 The Essence of Leadership: Views of a Form er C om m ander Lt Gen Evan W. Rosencrans, USAF, Retired 6 Soviet “Tactical” Aviation in the Postwar Period: Technological Change, Organizational Innovation, and Doctrinal Continuity Dr Jacob W. Kipp 8 Soviet Maskirovka Charles L. Smith 28 Doctrinal Deficiencies in Prisoner of War Command Col John R. Brancato, USAF 40 Superm aneuverability: Fighter Technology of the Future Col William D. -

Swarming and the Future of Conflict

SWARMING &The Future of Conflict A New Way of War Swarming is a seemingly amorphous, but deliberately structured, coordinated, strategic way to perform military strikes from all directions. It employs a sustainable pulsing of force and/or fire that is directed from both close-in and stand-off positions. It will work best—perhaps it will only work—if it is designed mainly around the deployment of myriad, small, dispersed, networked maneuver units. This calls for an organizational redesign—involving the creation of platoon-like “pods” joined in company-like “clusters”—that would keep but retool the most basic military unit structures. It is similar to the corporate redesign principle of “flattening,” which often removes or redesigns middle layers of management. This has proven successful in the ongoing revolution in business affairs and may prove equally useful in the military realm. From command and control of line units to logistics, profound shifts will have to occur to nurture this new “way of war.” This study examines the benefits—and also the costs and risks— Arquilla David Ronfeldt John of engaging in such serious doctrinal change. The emergence of a military doctrine based on swarming pods and clusters requires that defense policymakers develop new approaches to connectivity and control and achieve a new balance between the two. Far more than traditional approaches to battle, swarming clearly depends upon robust information flows. Securing these flows, therefore, can be seen as a necessary condition for successful swarming. Related Reading Arquilla, John, and David Ronfeldt, The Advent of Netwar, Santa Monica: RAND, MR-789-OSD, 1996. -

Napoleons Invasion of Russia

THE SPECIAL CAMPAIGN SERIES rown 8710 Clark co iousl su lied w ith Ma s a d C , , p y pp p n P la ns P rice s . n ot ea c . 5 lz . SAARBRUCK TO PA RIS : TH E FRANCO W M N A R. B COL . N . GER A y SISSO C PRATT, la te R . A. TH E R O - RK W 8 SS S AR . B U TU I H , 1 77 y MAJ OR F. MAURICE . F RE E R CKS B R : A III . D I U G STUDY IN WAR 1 862 . B W . R W , y MAJ OR G . ED AY. TH E CA MPA IGN OF MAGE NTA a nd O FE R NO 1 8 . B OL . W C . YLL Y C . B . S L I , 5 9 y H C , H E WA E RLOO C MP T I N. B L T A A G y CO . N la te R A . SISSO C . PRATT, . H E CAMPA G BO E M . T A 1 866. VI I N IN H I , - B LT . COL . R . GL N KE y G J U IC . E M . TH L E PZ G CA PA G 1 8 1 . B VII I I I N, 3 y N ~ C OL . F. C . B . la te R . E . MAUDE, , ’ M . GRA S C P I GN RG A VIII NT A A IN VI INI , W 1 86 TH E N M GN B P . 4 ( ILDER ESS CA PAI ) . -

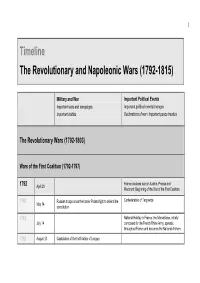

Timeline 1792-1815

1 Timeline The Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815) Military and War Important Political Events Important wars and campaigns Important political events/changes Important battles Declarations of war / Important peace treaties The Revolutionary Wars (1792-1803) Wars of the First Coalition (1792-1797) France declares war on Austria, Prussia and 1792 April 20 Piedmont: Beginning of the War of the First Coalition 1792 Russian troops cross the border Poland fight to defend the Confederation of Targowica May 14 constitution 1792 National Holiday in France: the Marseillaise, initially July 14 composed for the French Rhine Army, spreads throughout France and becomes the National Anthem 1792 August 23 Capitulation of the fortification of Longwy 2 1792 September 2 Capitulation of the fortification of Verdun September First phase of the „terreur“ (so called september 1792 5-7 murders) August/ 1792 Upheavals in Brittany, Mayenne and Vendée September Battle of Valmy (France versus Prussia/Austria) French 1792 September20 Victory 1792 September 21 Establishment of the first French Republic 1792 September 22 Die Armee unter Montesquiou dringt nach Savoyen vor 1792 September 23 The Austrians encircle Lille The convention splits his forces in eight armies: North, 1792 October 1 Ardennes, Moselle, Rhine, Vosges, Alps, Pyrénées, Interior 1792 October 3 Revolutionary troops occupy Basel 1792 October 4 Revolutionary troops occupy Worms 1792 October 27 Revolutionary troops enter Belgium The revolutionary troops occupy Jemappes (part of the 1792 November 6 austrian part of the Netherlands) 1792 November 9 Revolutionary troops occupy the Palatinate 1793 January 21 Louis XVI guillotined 1793 Russia and Prussia signed the Second Partition Great January 23 Poland with parts of Mazovia (Mazowsze) to Prussia; Podolia, Volhynia, and Lithuanian to Russia. -

200Th Anniversary of the Battle of Borodino

200th anniversary of the Battle of Borodino Первый Московский образовательный комплекс Структурное подразделение «Школа» Проект 2013-2014г.г. Английский язык THEME: Prepared by: Kirill Shinkarenko, Class 10“a” Подготовил: Шинкаренко Кирилл, 10 «a» класс Class leader: Olesya N. Ilyicheva Классный руководитель: Ильичёва О. Н. Teacher-consultant: Nataliya V. Kirilova Учитель-консультант: Кирилова Н.В. Kirill Shinkarenko 1 200th anniversary of the Battle of Borodino Shinkarenko Kirill . I am 16 years old. I chose this topic because I’m interested in the history of my country because our history is very important and that people do not have a future if they do not know their past. So I think that Battle of Borodino is one of the most important historical event. It left its mark not only in the history of Russia but other countries of the world. The battle of Borodino and the defeat of Napoleon is a symbol of courage and heroism. The war against Napoleon is an example for many generations of the peoples of our country. I remember the feat of our ancestors, and I'm proud of it. My achievements and awards. Kirill Shinkarenko 2 200th anniversary of the Battle of Borodino Kirill Shinkarenko 3 200th anniversary of the Battle of Borodino Kirill Shinkarenko 4 200th anniversary of the Battle of Borodino Purpose: To know more about history of Russia and its influence world history. Objective: A deeper understanding of English language, to learn new words and expressions, expand my knowledge. Contents: Introduction………………………………………………………… 6 The Causes -

Diplomacy and Murder in Tehran

Laurence Kelly F.R.S.L. is the author of a distinguished biography of Lermontov. He has studied and lived in Russia. ‘My book of the year is Laurence Kelly’s Diplomacy and Murder in Tehran. Kelly’s description of the literary and social life in St Petersburg and Moscow in the early 19th century is fascinating in itself and a portrait of a doomed generation of young, cultured aristocrats.’ Raymond Carr, The Spectator ‘Kelly’s highly readable and enjoyable book is the first biography in English of this intriguing figure. It is doubly fascinating: as an insight into a golden age of Russian literature, and for its diplomatic and military history of a region that still interests us.’ Jan Dalley, Financial Times ‘A vivid, dramatic story. .The exotic life of a supremely Russian, a well-told, informative tale, contemporary relevance – what more could the reader ask?’ George Walden, The Sunday Telegraph ‘Laurence Kelly’s wonderfully thorough life of Griboyedov, Diplomacy and Murder in Tehran is a first-class work of scholarship and a terrific, sensa- tional read. Not just a gripping story, but an important book.’ Philip Hensher, Books of the Year, The Spectator ‘In Laurence Kelly, Griboyedov has found a biographer who is at home in the princely salons of St Petersburg as he is in the souks of the Orient or the vine covered foothills of the Caucasus. An excellent book that is as impressive in scholarship as it is easy, indeed addictive, to read. A tour de force.’ Simon Sebag-Montefiore ‘Carefully researched and superbly planned…the book and its -

ESJF Report on Belarus Cemeteries

Belarus Jewish Cemeteries Survey and Research Project REPORT Prepared by the ESJF European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative Minsk 2017 Managing Editor: Philip Carmel Project Director: Yana Yanover Historical Research Director: Kateryna Malakhova, PhD Scientific Consultant: Alexey Yeryomenko Rabbinical Consultant: Rabbi Mordechai Reichinshtein Graphic Design: Yekaterina Kluchnik Copy Editor: Michele Goldsmith Office manager: Nataliya Videneyeva Survey Coordination: Ihor Travianko, Victoriya Dosuzheva, Alexander Konyukhov Data Coordination: Vladimir Girenkov, Stanislav Korolkov, Yaroslav Yaroslavskiy Surveyors: Alexey Yerokhin, Polina Hivrenko, Shimon Glazsheyn, Yitshak Reichinshtein, Ruslana Konyukhova Historical Research: Alexandra Fishel, Alena Andronatiy, Yan Galevsky, Yakov Yakovenko, Petr Yakovenko, Sabina Enenberg, Nadezhda Tolok, Oleksandr Khodakivsky, Kirill Danilchenko, Olha Lidovskaya, Vladimir Girenkov, Nadezhda Ufimtseva Translation: Marina Shteyman, Julia Zagorovsky We express our deep gratitude for all their assistance and advice to the following: Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Belarus Embassy of the United States of America to the Republic of Belarus Union of Religious Jewish Congregations of Belarus and to the Jewish communities of Brest, Homel, Hrodna, Mahilyow, Minsk and Vicebsk. This report was also greatly facilitated by the very generous cooperation of mayors and regional and local government authorities throughout the Republic of Belarus. CONTENTS ESJF European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative 4 Historical Jewish