Jacques Callot Etchings, Ca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rembrandt Packet Aruni and Morgan.Indd

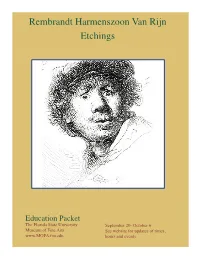

Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn Etchings Education Packet The Florida State University September 20- October 6 Museum of Fine Arts See website for updates of times, www.MOFA.fsu.edu hours and events. Table of Contents Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn Biography ...................................................................................................................................................2 Rembrandt’s Styles and Influences ............................................................................................................ 3 Printmaking Process ................................................................................................................................4-5 Focus on Individual Prints: Landscape with Three Trees ...................................................................................................................6-7 Hundred Guilder .....................................................................................................................................8-9 Beggar’s Family at the Door ................................................................................................................10-11 Suggested Art Activities Three Trees: Landscape Drawings .......................................................................................................12-13 Beggar’s Family at the Door: Canned Food Drive ................................................................................14-15 Hundred Guilder: Money Talks ..............................................................................................16-18 -

A Saltcellar in the Form of a Mermaid Holding a Shell Pen and Brown Ink and Grey Wash, Over an Underdrawing in Black Chalk

Stefano DELLA BELLA (Florence 1610 - Florence 1664) A Saltcellar in the Form of a Mermaid Holding a Shell Pen and brown ink and grey wash, over an underdrawing in black chalk. 179 x 83 mm. (7 x 3 1/4 in.) This charming drawing may be compared stylistically to such ornamental drawings by Stefano della Bella as a design for a garland in the Louvre. Similar drawings for table ornaments by the artist are in the Louvre, the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, the Uffizi and elsewhere. In the conception of this drawing, depicting a mermaid holding a shell above her head, the artist may have recalled Bernini’s Triton fountain in Rome, of which he made a study, now in the Louvre and similar in technique and handling to the present drawing, during his stay in the city in the 1630’s. Artist description: A gifted draughtsman and designer, Stefano della Bella was born into a family of artists. Apprenticed to a goldsmith, he later entered the workshop of the painter Giovanni Battista Vanni, and also received training in etching from Remigio Cantagallina. He came to be particularly influenced by the work of Jacques Callot, although it is unlikely that the two artists ever actually met. Della Bella’s first prints date to around 1627, and he eventually succeeded Callot as Medici court designer and printmaker, his commissions including etchings of public festivals, tournaments and banquets hosted by the Medici in Florence. Under the patronage of the Medici, Della Bella was sent in 1633 to Rome, where he made drawings after antique and Renaissance masters, landscapes and scenes of everyday life. -

Annual Report 1975

mm ; mm .... : ' ^: NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ANNUAL REPORT 1975 Property of the National Gallery of Art Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 70-173826 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D C. 20565. Copyright © 1976, Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art Inside cover photograph by Robert C. Lautman; photograph on page 91 by Helen Marcus; all other photographs by the photographic staff of the National Gallery of Art. Frontispiece: Bronze Galloping Horse, Han Dynasty, courtesy the People's Republic of China CONTENTS 6 ORGANIZATION 9 DIRECTOR'S REVIEW OF THE YEAR 20 DONORS AND ACQUISITIONS 47 LENDERS 50 NATIONAL PROGRAMS 50 Extension Program Development and Services 51 Art and Man 51 Loans of Works of Art 61 EDUCATIONAL SERVICES 61 Lectures, Tours, Texts, Films 64 Art Information Service 65 DEPARTMENTAL REPORTS 65 Curatorial Departments 66 Graphic Arts 67 Library 68 Photographic Archives 69 Conservation Treatment and Research 72 Editor's Office 72 Exhibitions and Loans 74 Registrar's Office 74 Installation and Design 75 Photographic Laboratory Services 76 STAFF ACTIVITIES 82 ADVANCED STUDY AND RESEARCH, AND SCHOLARLY PUBLICATIONS 86 MUSIC AT THE GALLERY 89 PUBLICATIONS SERVICE 90 BUILDING MAINTENANCE, SECURITY AND ATTENDANCE 92 APPROPRIATIONS 93 EAST BUILDING 94 ROSTER OF EMPLOYEES ORGANIZATION The 38th annual report of the National Gallery of Art reflects another year of continuing growth and change. Although formally established by Congress as a bureau of the Smithsonian Institution, the National Gallery is an autonomous and separately administered organization and is gov- erned by its own Board of Trustees. -

Jacques Callot and the Baroque Print, June 17, 2011-November 6, 2011

Jacques Callot and the Baroque Print, June 17, 2011-November 6, 2011 One of the most prolific and versatile graphic artists in Western art history, the French printmaker Jacques Callot created over 1,400 prints by the time he died in 1635 at the age of forty-three. With subjects ranging from the frivolous festivals of princes to the grim consequences of war, Callot’s mixture of reality and fanciful imagination inspired artists from Rembrandt van Rijn in his own era to Francisco de Goya two hundred years later. In these galleries, Callot’s works are shown next to those of his contemporaries to gain a deeper understanding of his influence. Born into a noble family in 1592 in Nancy in the Duchy of Lorraine (now France), Callot traveled to Rome at the age of sixteen to learn printmaking. By 1614, he was in Florence working for Cosimo II de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. After the death of the Grand Duke in 1621, Callot returned to Nancy, where he entered the service of the dukes of Lorraine and made prints for other European monarchs and the Parisian publisher Israël Henriet. Callot perfected the stepped etching technique, which consisted of exposing copperplates to multiple acid baths while shielding certain areas from the chemical with a hard, waxy ground (see the book illustration in the adjoining gallery). This process contributed to different depths of etched lines and thus striking light and spatial qualities when the plate was inked and printed. Callot may have invented the échoppe, a tool with a curved tip that he used to sweep through the hard ground to create curved and swelled lines in imitation of engraving. -

Old Master Prints

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6n39n8g8 Online items available Old Master Prints Processed by Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, UCLA Hammer Museum staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Layna White Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts UCLA Hammer Museum University of California, Los Angeles 10899 Wilshire Blvd. Los Angeles, California 90024-4201 Phone: (310) 443-7078 Fax: (310) 443-7099 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.hammer.ucla.edu © 2003 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Old Master Prints 1 Old Master Prints Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, UCLA Hammer Museum University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, California Contact Information Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts UCLA Hammer Museum University of California, Los Angeles 10899 Wilshire Blvd. Los Angeles, California 90024-4201 Phone: (310) 443-7078 Fax: (310) 443-7099 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.hammer.ucla.edu Processed by: Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, UCLA Hammer Museum staff Date Completed: 2/21/2003 Encoded by: Layna White © 2003 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Old Master Prints Repository: Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, UCLA Hammer Museum Los Angeles, CA 90024 Language: English. Publication Rights For publication information, please contact Susan Shin, Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, [email protected] Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Collection of the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, UCLA. [Item credit line, if given] Notes In 15th-century Europe, the invention of the printed image coincided with both the wide availability of paper and the invention of moveable type in the West. -

The Madden/Arnholz Collection

Old Master Prints: The Madden/Arnholz Collection Curated by Janet & John Banville 22 March - 12 June 2011 Exhibition Notes for Primary School Teachers General Information Fritz Arnholz was born in Berlin in 1897, into a wealthy merchant family. He studied medicine, graduating in 1924, and worked as a doctor in his native city until 1939 when, as a Jew, he was forced to flee Germany for Britain—his parents were already dead, but his brother was murdered by the Nazis in Auschwitz. He worked as house physician in a number of London hospitals, and then in the Royal Army Medical Corps, which he left after the war in the rank of captain. He joined a general medical practice in Fulham, where he was to work for the rest of his life. He was a very popular doctor, known for his humour as much as for his medical expertise and his care and compassion for his patients. His met his future wife, Etain Madden, in the early 1960s. Although she was appreciably younger than he, they were an obvious match from the start. Etain, born in Ireland to politically active parents, was brought up in England but never lost her strong sense of herself as an Irish patriot; she was also a left-wing activist and a committed feminist. The Madden-Arnholz marriage was blissful if brief—Dr Arnholz had been diagnosed with cancer shortly before they were married. The couple shared deep intellectual interests, especially literature and music, as well as a wickedly subversive sense of humour. Etain was a student of philosophy, while Fritz, who had studied in Berlin under Artur Schnabel, was a pianist of concert standard, with a special affinity for the keyboard music of Bach and Mozart. -

The Artful Context of Rembrandt's Etching

Volume 5, Issue 2 (Summer 2013) Begging for Attention: The Artful Context of Rembrandt’s Etching “Beggar Seated on a Bank” Stephanie S. Dickey Recommended Citation: Stephanie Dickey, “Begging for Attention: The Artful Context of Rembrandt’s Etching “Beggar Seated on a Bank” JHNA 5:2 (Summer 2013), DOI:10.5092/jhna.2013.5.2.8 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/begging-for-attention-artful-context-rembrandts-etching- beggar-seated-on-a-bank/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This is a revised PDF that may contain different page numbers from the previous version. Use electronic searching to locate passages. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 5:2 (Summer 2013) 1 BEGGING FOR ATTENTION: THE ARTFUL CONTEXT OF REMBRANDT’S ETCHING “BEGGAR SEATED ON A BANK” Stephanie S. Dickey Rembrandt’s representation of his own features in Beggar Seated on a Bank (etching, 1630) gains resonance in the context of a visual and literary tradition depicting “art impoverished” and reflects the artist’s struggle for recognition from patrons such as Stadhouder Frederik Hendrik at a pivotal moment in his early career. 10.5092/jhna.2013.5.2.8 1 wo figural motifs recur frequently in Rembrandt’s etchings of the 1630s: ragged peasants and the artist’s own startlingly expressive face. On a copperplate that he treated like a page from a sketchbook, these disparate subjects are juxtaposed.1 And in an etching of 1630, Tthey merge, as Rembrandt himself takes on the role of a hunched figure seated on a rocky hillock (fig. -

Jacques Callot at the Medici Court

SPECTACULARLY SMALL: JACQUES CALLOT AT THE MEDICI COURT Nina Eugenia Serebrennikov In his short twelve-year reign, the Grand Duke of Tuscany Cosimo II de’ Medici sponsored numerous public spectacles for the entertainment of his subjects. To commemorate these events Jacques Callot developed considerable skill in rendering throngs of spectators admiring that princely largesse. The apogee of this lexicon of spectacle was Callot’s Fair at Impruneta. Dedicating it to the grand duke, he depicted well over a thousand figures engaged in nearly as many separate activities. But there would be no place for the large writ small in seventeenth-century academic theory; it was a taste and skill that was virtually extinguished with the death of Cosimo II and Callot. DOI: 10.18277/makf.2015.12 n the second volume of Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past the young Marcel recounts his first experience of the theater. He accompanies his grandmother to a matinee performance of Racine’s Phèdre starring the renowned Iactress Berma, whom the boy idolizes, I told my grandmother that I could not see very well; she handed me her glasses. Only, when one believes in the reality of a thing, making it visible by artificial means is not quite the same as feeling that it is close at hand. I thought now that it was no longer Berma at whom I was looking, but her image in a magnifying glass. I put the glasses down, but then possibly the image that my eye received of her, diminished by distance, was no more exact; which of the two Bermas was the real?1 The issue of which version to believe—that seen by the naked eye, or that seen through a lens—rises repeatedly in the history of optics. -

Against Reason: Anti/Enlightenment Prints by Callot, Hogarth, Piranesi, and Goya

Against Reason: Anti/Enlightenment Prints by Callot, Hogarth, Piranesi, and Goya Curated by students in the Exhibition Seminar, Department of Art and Art History, Grinnell College Under the Direction of Assistant Professor of Art History, J. Vanessa Lyon April 3—August 2, 2015 Faulconer Gallery Bucksbaum Center for the Arts Grinnell College Participants in the Exhibition Seminar Fall 2014: Elizabeth Allen ‘16 Timothy McCall ‘15 Mai Pham ‘16 Maria Shevelkina ‘15 Dana Sly ‘15 Hannah Storch ‘16 Emma Vale ‘15 Published on the occasion of the exhibition Against Reason: Anti/Enlightenment Prints by Callot, Hogarth, Piranesi, and Goya 3 April–2 August 2015 Lender to the Exhibition: University of Iowa Museum of Art Iowa City, Iowa ©2015 Grinnell College Faulconer Gallery, Bucksbaum Center for the Arts 1108 Park Street Grinnell, Iowa 50112-1690 641-269-4660 www.grinnell.edu/faulconergallery [email protected] Essays ©2015 the respective authors. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, electronic or otherwise, without written permission from Faulconer Gallery, Grinnell College. ISBN: ISBN 978-0-9898825-2-1 The catalogue’s cover images are reproductions of the embossed leather bindings of a 1584 edition of Martin de Azpilcueta’s Enchiridion (BV194.C7A91x). This canonical manual of Catholic casuistry is housed in Grinnell College’s Special Collections and Archives. Faulconer Gallery Staff Conni Gause, Administrative Support Assistant Milton -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE from THE FRICK COLLECTION 1 EAST 70TH STREET • NEW YORK • NEW YORK 10021 • TELEPHONE (212) 288-0700 • FAX (212) 628-4417 STUNNING DRAWINGS FROM WEIMAR MUSEUMS TO BE PRESENTED IN THE UNITED STATES FOR THE FIRST TIME Core of these Little-Known Collections Connected to Goethe June 1 through August 7, 2005 From Callot to Greuze: French Drawings from Weimar, an exhibition opening on June 1, 2005, at The Frick Collection presents to American audiences a selection of approximately seventy drawings from the Schlossmuseum and the Goethe-Nationalmuseum in Weimar, Germany, and offers a unique viewing opportunity as many of these works have never before been seen outside of the former Eastern bloc countries. (The two institutions—with their collections, gardens, and buildings— united in 2003 and are now known as Stiftung Weimarer Klassik und Kunstsammlungen.) The accompanying catalogue also marks the first François Boucher (1703–1770) time that many of these masterworks have been published. Sheets by A Triton Holding a Stoup in His Hands, date unknown Stumped black chalk, heightened with white chalk, on cream paper, 328 x 297 mm Jacques Callot, Charles Lebrun, Claude Lorrain, Jacques Bellange, Schlossmuseum–KK 9000 Simon Vouet, Jean-Antoine Watteau, François Boucher, Charles-Joseph Natoire, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, and Charles-Louis Clérisseau, among others, are included, promising to shed new light on the individual oeuvres of these artists as well as deepen our understanding of their practice as draftsmen within the context of other French masters. Comments Anne L. Poulet, Director of The Frick Collection, “this project presents the most complete assessment to date of Weimar’s French seventeenth- and eighteenth-century drawings, and we are pleased to offer most of our visitors—with both the exhibition and publication—their first viewing of this incredible collection. -

Object Journal 19

HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.14324/111.2396-9008.025 THE BODY RE-IMAGINED: THE BIZZARIE DI VARIE FIGURE AND PERFORMATIVE CYCLES OF PRINTS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY FLORENCE Laura Scalabrella Spada here are images that seem to defy their place in time. The remarkable images in a collection of early seventeenth-century prints entitled TBizzarie di Varie Figure (1624), seemingly disavowing their own historical contingency, present such a challenge. Turning over the ffty plates of this album is like rotating a kaleidoscope, an experience that suggests limitless possibilities. A myriad of performative fgures follow one another, they are unrestrained, transgressive, without apparent order or logic. As one skims through the leaves, a carnival of actors, dancers, and fencers display not only sheer expressiveness but also transformative potential in which human, mechanical and even kinetic forces intersect and become something else. This display of the body, conceptualized in transformative, apparently limitless forms, seems inconceivable for 1624, the date etched on the album’s frontispiece. Appearing to emerge rather from improvised drawing than from their physical inscription on paper as tangible matter, these etchings confound the very medium in which they appear: the fgures seem to overcome their inscription on paper and foat from plane to plane outside of gravity (fgures 1, 2 and 3). The process of etching, which involves the use of acids to corrode the plate, is less forceful than engraving; its expressive potential allowed artists to reach a higher level of detail within the images, to achieve a wider tonal range, and to produce vibrant fgures.1 These prints move towards the total undoing of the body’s traditional frame, yet are anchored to a visual technology of repetition and aggregation, which asserts the body’s fnal fnished form, but also seems to constantly change it. -

Rembrandt's “Little Swimmers” in Context

REMBRANDT’S “LITTLE SWIMMERS” IN CONTEXT Stephanie S. Dickey In an etching of 1651, Rembrandt depicts a group of men swimming in a forest glade. His treatment of the theme is unconventional not only in the starkly unidealized rendering of the figures but also in their mood of pensive isolation. This essay situates Rembrandt’s etching within a surprisingly complex visual tradition, revealing associations with social class, masculinity, and the struggle of man against nature. Artists who contributed to this tradition included Italian and Northern masters represented in Rembrandt’s print collection as well as contemporaries active in his own circle. DOI: 10.18277/makf.2015.05 or the festchrift in 2011 honoring our distinguished colleague Eric Jan Sluijter, Alison Kettering contributed an insightful essay on representations of the male nude by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669).1 Rembrandt’s female nudes have attracted critical notice since his own time,2 but much less attention has been paid to depictions Fof the male body either in his work or in Dutch art more generally. As co-editor of the Sluijter festschrift, I had the pleasure of discussing this topic with Alison, and of puzzling together over a small etching completed by Rembrandt in 1651 (fig. 1). Modern cataloguers usually entitle it The Bathers, the title I will retain here, but its nickname among seventeenth-century collectors was De zwemmetjes, or “The Little Swimmers.” Significantly, this title is first recorded in the estate inventory of the print-seller Clement de Jonghe, whose portrait Rembrandt etched in 1651, the same year as The Bathers.3 Rembrandt produced only a single state of the plate, but watermark evidence indicates that he reprinted it several times, occasionally (as in fig.