Rembrandt's “Little Swimmers” in Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rembrandt Packet Aruni and Morgan.Indd

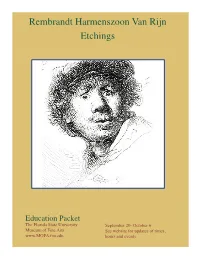

Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn Etchings Education Packet The Florida State University September 20- October 6 Museum of Fine Arts See website for updates of times, www.MOFA.fsu.edu hours and events. Table of Contents Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn Biography ...................................................................................................................................................2 Rembrandt’s Styles and Influences ............................................................................................................ 3 Printmaking Process ................................................................................................................................4-5 Focus on Individual Prints: Landscape with Three Trees ...................................................................................................................6-7 Hundred Guilder .....................................................................................................................................8-9 Beggar’s Family at the Door ................................................................................................................10-11 Suggested Art Activities Three Trees: Landscape Drawings .......................................................................................................12-13 Beggar’s Family at the Door: Canned Food Drive ................................................................................14-15 Hundred Guilder: Money Talks ..............................................................................................16-18 -

Un Univers Intime Paintings in the Frits Lugt Collection 1St March - 27 Th May 2012

Institut Centre culturel 121 rue de Lille - 75007 Paris Néerlandais des Pays-Bas www.institutneerlandais.com UN UNIVERS INTIME PAINTINGS IN THE FRITS LUGT COLLECTION 1ST MARCH - 27 TH MAY 2012 MAI 2012 Pieter Jansz. Saenredam (Assendelft 1597 - 1665 Haarlem) Choir of the Church of St Bavo in Haarlem, Seen from the Christmas Chapel , 1636 UN UNIVERS Paintings in the Frits INTIME Lugt Collection Press Release The paintings of the Frits Lugt Collection - topographical view of a village in the Netherlands. Fondation Custodia leave their home for the The same goes for the landscape with trees by Jan Institut Néerlandais, displaying for the first time Lievens, a companion of Rembrandt in his early the full scope of the collection! years, of whom very few painted landscapes are known. The exhibition Un Univers intime offers a rare Again, the peaceful expanse of water in the View of a opportunity to view this outstanding collection of Canal with Sailing Boats and a Windmill is an exception pictures (Berchem, Saenredam, Maes, Teniers, in the career of Ludolf Backhuysen, painter of Guardi, Largillière, Isabey, Bonington...), expanded tempestuous seascapes. in the past two years with another hundred works. The intimate interiors of Hôtel Turgot, home to the Frits Lugt Collection, do indeed keep many treasures which remain a secret to the public. The exhibition presents this collection which was created gradually, with great passion and discernment, over nearly a century, in a selection of 115 paintings, including masterpieces of the Dutch Golden Age, together with Flemish, Italian, French and Danish paintings. DUTCH OF NOTE Fig. -

Sztuki Piękne)

Sebastian Borowicz Rozdział VII W stronę realizmu – wiek XVII (sztuki piękne) „Nikt bardziej nie upodabnia się do szaleńca niż pijany”1079. „Mistrzami malarstwa są ci, którzy najbardziej zbliżają się do życia”1080. Wizualna sekcja starości Wiek XVII to czas rozkwitu nowej, realistycznej sztuki, opartej już nie tyle na perspektywie albertiańskiej, ile kepleriańskiej1081; to również okres malarskiej „sekcji” starości. Nigdy wcześniej i nigdy później w historii europejskiego malarstwa, wyobrażenia starych kobiet nie były tak liczne i tak różnicowane: od portretu realistycznego1082 1079 „NIL. SIMILIVS. INSANO. QVAM. EBRIVS” – inskrypcja umieszczona na kartuszu, w górnej części obrazu Jacoba Jordaensa Król pije, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wiedeń. 1080 Gerbrand Bredero (1585–1618), poeta niderlandzki. Cyt. za: W. Łysiak, Malarstwo białego człowieka, t. 4, Warszawa 2010, s. 353 (tłum. nieco zmienione). 1081 S. Alpers, The Art of Describing – Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century, Chicago 1993; J. Friday, Photography and the Representation of Vision, „The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism” 59:4 (2001), s. 351–362. 1082 Np. barokowy portret trumienny. Zob. także: Rembrandt, Modląca się staruszka lub Matka malarza (1630), Residenzgalerie, Salzburg; Abraham Bloemaert, Głowa starej kobiety (1632), kolekcja prywatna; Michiel Sweerts, Głowa starej kobiety (1654), J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Monogramista IS, Stara kobieta (1651), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wiedeń. 314 Sebastian Borowicz po wyobrażenia alegoryczne1083, postacie biblijne1084, mitologiczne1085 czy sceny rodzajowe1086; od obrazów o charakterze historycznodokumentacyjnym po wyobrażenia należące do sfery historii idei1087, wpisujące się zarówno w pozy tywne1088, jak i negatywne klisze kulturowe; począwszy od Prorokini Anny Rembrandta, przez portrety ubogich staruszek1089, nobliwe portrety zamoż nych, starych kobiet1090, obrazy kobiet zanurzonych w lekturze filozoficznej1091 1083 Bernardo Strozzi, Stara kobieta przed lustrem lub Stara zalotnica (1615), Музей изобразительных искусств им. -

The Dutch Golden Age: a New Aurea Ætas? the Revival of a Myth in the Seventeenth-Century Republic Geneva, 31 May – 2 June 2018

The Dutch Golden Age: a new aurea ætas? The revival of a myth in the seventeenth-century Republic Geneva, 31 May – 2 June 2018 « ’T was in dien tyd de Gulde Eeuw voor de Konst, en de goude appelen (nu door akelige wegen en zweet naauw te vinden) dropen den Konstenaars van zelf in den mond » (‘This time was the Golden Age for Art, and the golden apples (now hardly to be found if by difficult roads and sweat) fell spontaneously in the mouths of Artists.’) Arnold Houbraken, De groote schouburgh der nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen, 1718-1721, vol. II, p. 237.1 In 1719, the painter Arnold Houbraken voiced his regret about the end of the prosperity that had reigned in the Dutch Republic around the middle of the seventeenth century. He indicates this period as especially favorable to artists and speaks of a ‘golden age for art’ (Gulde Eeuw voor de Konst). But what exactly was Houbraken talking about? The word eeuw is ambiguous: it could refer to the length of a century as well as to an undetermined period, relatively long and historically undefined. In fact, since the sixteenth century, the expression gulde(n) eeuw or goude(n) eeuw referred to two separate realities as they can be distinguished today:2 the ‘golden century’, that is to say a period that is part of history; and the ‘golden age’, a mythical epoch under the reign of Saturn, during which men and women lived like gods, were loved by them, and enjoyed peace and happiness and harmony with nature. -

Petitioners, —V.—

No. _______ IN THE Supreme Court of the United States HEIDI C. LILLEYd, KIA SINCLAIR, and GINGER M. PIERRO, Petitioners, —v.— THE STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE, Respondent. ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF NEW HAMPSHIRE PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI ERIC ALAN ISAACSON Counsel of Record LAW OFFICE OF ERIC ALAN ISAACSON 6580 Avenida Mirola La Jolla, California 92037 (858) 263-9581 [email protected] DAN HYNES LIBERTY LEGAL SERVICES PLLC 212 Coolidge Avenue Manchester, New Hampshire 03101 (603) 583-4444 Counsel for Petitioners i QUESTIONS PRESENTED Three women active in the Free the Nipple Movement were convicted of violating a Laconia, N.H. Ordinance prohibiting public exposure of “the female breast with less than a fully opaque covering of any part of the nipple.” Laconia, N.H., Code of Ordinances ch. 180, art. I, §§180-2(3), 180-4. The Supreme Court of New Hampshire affirmed their convictions in a published opinion rejecting state and federal Equal Protection Clause defenses. Contrary to federal appellate decisions, New Hampshire’s high court held an ordinance punishing only females for exposure of their areolas does not classify on the basis of gender. Alternatively, New Hampshire’s high court held the Ordinance would survive intermediate scrutiny anyway—a holding directly at odds with a recent Tenth Circuit decision, which in turn conflicts with decisions of the Seventh and Eighth Circuits. The questions presented are: 1. Does an ordinance expressly punishing only women, but not men, for identical conduct—being topless in public—classify on the basis of gender? 2. -

Sara Fox [email protected] Tel +1 212 636 2680

For Immediate Release May 18, 2012 Contact: Sara Fox [email protected] tel +1 212 636 2680 A MASTERPIECE BY ROMANINO, A REDISCOVERED RUBENS, AND A PAIR OF HUBERT ROBERT PAINTINGS LEAD CHRISTIE’S OLD MASTER PAINTINGS SALE, JUNE 6 Sale Includes Several Stunning Works From Museum Collections, Sold To Benefit Acquisitions Funds GIROLAMO ROMANINO (Brescia 1484/87-1560) Christ Carrying the Cross Estimate: $2,500,000-3,500,000 New York — Christie’s is pleased to announce its summer sale in New York of Old Master Paintings on June 6, 2012, at 5 pm, which primarily consists of works from private collections and institutions that are fresh to the market. The star lot is the 16th-century masterpiece of the Italian High Renaissance, Christ Carrying the Cross (estimate: $2,500,000-3,500,000) by Girolamo Romanino; see separate press release. With nearly 100 works by great French, Italian, Flemish, Dutch and British masters of the 15th through the 19th centuries, the sale includes works by Sir Peter Paul Rubens, Hubert Robert, Jan Breughel I, and his brother Pieter Brueghel II, among others. The auction is expected to achieve in excess of $10 million. 1 The sale is highlighted by several important paintings long hidden away in private collections, such as an oil-on-panel sketch for The Adoration of the Magi (pictured right; estimate: $500,000 - $1,000,000), by Sir Peter Paul Rubens (Siegen, Westphalia 1577- 1640 Antwerp). This unpublished panel comes fresh to market from a private Virginia collection, where it had been in one family for three generations. -

A Saltcellar in the Form of a Mermaid Holding a Shell Pen and Brown Ink and Grey Wash, Over an Underdrawing in Black Chalk

Stefano DELLA BELLA (Florence 1610 - Florence 1664) A Saltcellar in the Form of a Mermaid Holding a Shell Pen and brown ink and grey wash, over an underdrawing in black chalk. 179 x 83 mm. (7 x 3 1/4 in.) This charming drawing may be compared stylistically to such ornamental drawings by Stefano della Bella as a design for a garland in the Louvre. Similar drawings for table ornaments by the artist are in the Louvre, the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, the Uffizi and elsewhere. In the conception of this drawing, depicting a mermaid holding a shell above her head, the artist may have recalled Bernini’s Triton fountain in Rome, of which he made a study, now in the Louvre and similar in technique and handling to the present drawing, during his stay in the city in the 1630’s. Artist description: A gifted draughtsman and designer, Stefano della Bella was born into a family of artists. Apprenticed to a goldsmith, he later entered the workshop of the painter Giovanni Battista Vanni, and also received training in etching from Remigio Cantagallina. He came to be particularly influenced by the work of Jacques Callot, although it is unlikely that the two artists ever actually met. Della Bella’s first prints date to around 1627, and he eventually succeeded Callot as Medici court designer and printmaker, his commissions including etchings of public festivals, tournaments and banquets hosted by the Medici in Florence. Under the patronage of the Medici, Della Bella was sent in 1633 to Rome, where he made drawings after antique and Renaissance masters, landscapes and scenes of everyday life. -

HNA April 11 Cover-Final.Indd

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 28, No. 1 April 2011 Jacob Cats (1741-1799), Summer Landscape, pen and brown ink and wash, 270-359 mm. Hamburger Kunsthalle. Photo: Christoph Irrgang Exhibited in “Bruegel, Rembrandt & Co. Niederländische Zeichnungen 1450-1850”, June 17 – September 11, 2011, on the occasion of the publication of Annemarie Stefes, Niederländische Zeichnungen 1450-1850, Kupferstichkabinett der Hamburger Kunsthalle (see under New Titles) HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone/Fax: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President - Stephanie Dickey (2009–2013) Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art Queen’s University Kingston ON K7L 3N6 Canada Vice-President - Amy Golahny (2009–2013) Lycoming College Williamsport, PA 17701 Treasurer - Rebecca Brienen University of Miami Art & Art History Department PO Box 248106 Coral Gables FL 33124-2618 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Board Members Contents Dagmar Eichberger (2008–2012) HNA News ............................................................................1 Wayne Franits (2009–2013) Matt Kavaler (2008–2012) Personalia ............................................................................... 2 Henry Luttikhuizen (2009 and 2010–2014) Exhibitions -

Key to the People and Art in Samuel F. B. Morse's Gallery of the Louvre

15 21 26 2 13 4 8 32 35 22 5 16 27 14 33 1 9 6 23 17 28 34 3 36 7 10 24 18 29 39 C 19 31 11 12 G 20 25 30 38 37 40 D A F E H B Key to the People and Art in Samuel F. B. Morse’s Gallery of the Louvre In an effort to educate his American audience, Samuel Morse published Descriptive Catalogue of the Pictures. Thirty-seven in Number, from the Most Celebrated Masters, Copied into the “Gallery of the Louvre” (New York, 1833). The updated version of Morse’s key to the pictures presented here reflects current scholarship. Although Morse never identified the people represented in his painting, this key includes the possible identities of some of them. Exiting the gallery are a woman and little girl dressed in provincial costumes, suggesting the broad appeal of the Louvre and the educational benefits it afforded. PEOPLE 19. Paolo Caliari, known as Veronese (1528–1588, Italian), Christ Carrying A. Samuel F. B. Morse the Cross B. Susan Walker Morse, daughter of Morse 20. Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519, Italian), Mona Lisa C. James Fenimore Cooper, author and friend of Morse 21. Antonio Allegri, known as Correggio (c. 1489?–1534, Italian), Mystic D. Susan DeLancy Fenimore Cooper Marriage of St. Catherine of Alexandria E. Susan Fenimore Cooper, daughter of James and Susan DeLancy 22. Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640, Flemish), Lot and His Family Fleeing Fenimore Cooper Sodom F. Richard W. Habersham, artist and Morse’s roommate in Paris 23. -

Sotheby's Old Master & British Paintings Evening Sale London | 08 Jul 2015, 07:00 PM | L15033

Sotheby's Old Master & British Paintings Evening Sale London | 08 Jul 2015, 07:00 PM | L15033 LOT 14 THE PROPERTY OF A LADY JACOB ISAACKSZ. VAN RUISDAEL HAARLEM 1628/9 - 1682 AMSTERDAM HILLY WOODED LANDSCAPE WITH A FALCONER AND A HORSEMAN signed in monogram lower right: JvR oil on canvas 101 by 127.5 cm.; 39 3/4 by 50 1/4 in. ESTIMATE 500,000-700,000 GBP PROVENANCE Lady Elisabeth Pringle, London, 1877; With Galerie Charles Sedelmeyer, Paris, 1898; Mrs. P. C. Handford, Chicago; Her sale, New York, American Art Association, 30 January 1902, lot 59; William B. Leeds, New York; His sale, London, Sotheby’s, 30 June 1965, lot 25; L. Greenwell; Anonymous sale ('The Property of a Private Collector'), New York, Sotheby’s, 7 June 1984, lot 76, for $517,000; Gerald and Linda Guterman, New York; Their sale, New York, Sotheby’s, 14 January 1988, lot 32; Anonymous sale New York, Sotheby’s, 2 June 1989, lot 16, for $297,000; With Verner Amell, London 1991; Acquired from the above by Hans P. Wertitsch, Vienna; Thence by family descent. EXHIBITED London, Royal Academy, Winter Exhibition, 1877, no. 25; New York, Minkskoff Cultural Centre, The Golden Ambience: Dutch Landscape Painting in the 17th Century, 1985, no. 10; Hamburg, Kunsthalle, Jacob van Ruisdael – Die Revolution der Landschaft, 18 January – 1 April 2002, and Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, 27 April – 29 July 2002, no. 31; Vienna, Akademie der Bildenden Künste, on loan since 2010. LITERATURE C. Sedelmeyer, Catalogue of 300 paintings, Paris 1898, pp. 1967–68, no. 175, reproduced; C. -

National Gallery of Art April 23, 1982 - October 31, 1982

Note to Editors; The revised dates and itinerary for the exhibition Mauritshuis; Dutch Painting of the Golden Age from the Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, are as follows: National Gallery of Art April 23, 1982 - October 31, 1982 Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas November 20, 1982 - January 30, 1983 The Art Institute of Chicago February 26, 1983 - May 29, 1983 Los Angeles County Museum of Art June 30, 1983 - September 11, 1983 \ i: w s 111; i, i« \ s i; STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 . 7374215 FOURTH extension 51: ADVANCE FACT SHEET Exhibition: Mauritshuis: Dutch Painting of the Golden Age from the Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague Dates: April 23, 1982 - September 6, 1982 Description: Forty outstanding examples of 17th-century Dutch painting from the Mauritshuis, the Royal Picture Gallery of The Netherlands, will begin a national tour which coincides with the bicentennial anniversary of Dutch-American diplomatic relations. Johannes Vermeer's Head of a Young Girl, Carl Fabritius' Goldfinch, Frans Hals' Laughing Boy and three masterworks by Rembrandt will be on view, as will paintings by Jan Steen, Jan van Goyen, Jacob van Ruisdael, Gerard ter Borch and other masters from this unsurpassed period of Dutch art. Itinerary: After opening at the National Gallery, the exhibition will travel to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (October 6, 1982 - January 30, 1983); the Art Institute of Chicago (February 26, 1983 - May 29, 1983); and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (June 30, 1983 - September 11, 1983). Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr., Curator, Dutch Painting, and Dodge Thompson, Executive Curator, National Gallery of Art, worked on organizing the exhibition for the American tour. -

November 2012 Newsletter

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 29, No. 2 November 2012 Jan and/or Hubert van Eyck, The Three Marys at the Tomb, c. 1425-1435. Oil on panel. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. In the exhibition “De weg naar Van Eyck,” Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, October 13, 2012 – February 10, 2013. HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President - Stephanie Dickey (2009–2013) Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art Queen’s University Kingston ON K7L 3N6 Canada Vice-President - Amy Golahny (2009–2013) Lycoming College Williamsport, PA 17701 Treasurer - Rebecca Brienen University of Miami Art & Art History Department PO Box 248106 Coral Gables FL 33124-2618 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Contents Board Members President's Message .............................................................. 1 Paul Crenshaw (2012-2016) HNA News ............................................................................1 Wayne Franits (2009-2013) Personalia ............................................................................... 2 Martha Hollander (2012-2016) Exhibitions ............................................................................ 3 Henry Luttikhuizen (2009 and 2010-2014)