Rembrandt Packet Aruni and Morgan.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Good Friday Order of Service

first christian reformed church sioux center a reflection on the passion of our lord according to the gospel of John ~ good friday ~ april 10, 2020 order of service Prelude ~ “Were you There” Linker “O Sacred Head” Burkhardt Welcome Call to Worship Today we remember Jesus was crucified. He was pierced for our transgressions. He suffered and died for our iniquities. We remember the sacrifice of our Lord with gratitude because his death gives us life and brings redemption to the world. Let us worship our Savior. Prayer of Invocation O God, who for our redemption gave your only Son to the death of the cross, and by his glorious resurrection delivered us from the power of our enemy: grant us so to die daily to sin, that we may evermore live with him in the joy of his resurrection, now and forever. Prayers of Intercession and Illumination Hymn: “Let All Mortal Flesh Keep Silence,” verses 1-3 Hymn continued on the next page. Scripture Reading: John 18.1-14 ~ Jesus’ Arrest and Betrayal Hymn: “Meekness and Majesty” ~ Lif Up Your Hearts 157, verses 1-3 Verse 1: Verse 2: Meekness and majesty, manhood and Deity Father's pure radiance, perfect in innocence, in perfect harmony, the Man who is God. yet learns obedience to death on a cross, Lord of eternity dwells in humanity, suffering to give us life, conquering through sacrifice, kneels in humility, and washes our feet. and, as they crucify, prays, “Father forgive.” Chorus: Chorus Oh, what a mystery—meekness and majesty; bow down and worship, for this is your God. -

A Saltcellar in the Form of a Mermaid Holding a Shell Pen and Brown Ink and Grey Wash, Over an Underdrawing in Black Chalk

Stefano DELLA BELLA (Florence 1610 - Florence 1664) A Saltcellar in the Form of a Mermaid Holding a Shell Pen and brown ink and grey wash, over an underdrawing in black chalk. 179 x 83 mm. (7 x 3 1/4 in.) This charming drawing may be compared stylistically to such ornamental drawings by Stefano della Bella as a design for a garland in the Louvre. Similar drawings for table ornaments by the artist are in the Louvre, the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, the Uffizi and elsewhere. In the conception of this drawing, depicting a mermaid holding a shell above her head, the artist may have recalled Bernini’s Triton fountain in Rome, of which he made a study, now in the Louvre and similar in technique and handling to the present drawing, during his stay in the city in the 1630’s. Artist description: A gifted draughtsman and designer, Stefano della Bella was born into a family of artists. Apprenticed to a goldsmith, he later entered the workshop of the painter Giovanni Battista Vanni, and also received training in etching from Remigio Cantagallina. He came to be particularly influenced by the work of Jacques Callot, although it is unlikely that the two artists ever actually met. Della Bella’s first prints date to around 1627, and he eventually succeeded Callot as Medici court designer and printmaker, his commissions including etchings of public festivals, tournaments and banquets hosted by the Medici in Florence. Under the patronage of the Medici, Della Bella was sent in 1633 to Rome, where he made drawings after antique and Renaissance masters, landscapes and scenes of everyday life. -

Rembrandt, with a Complete List of His Etchings by Arthur Mayger Hind

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Rembrandt, With a Complete List of His Etchings by Arthur Mayger Hind This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Rembrandt, With a Complete List of His Etchings Author: Arthur Mayger Hind Release Date: February 5, 2010 [Ebook 31183] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK REMBRANDT, WITH A COMPLETE LIST OF HIS ETCHINGS *** Rembrandt, With a Complete List of his Etchings Arthur M. Hind Fredk. A. Stokes Company 1912 144, II. Rembrandt and his Wife, Saskia, 1636, B. 19 Contents REMBRANDT . .1 BOOKS OF REFERENCE . .7 A CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF REMBRANDT'S ETCHINGS . .9 Illustrations 144, II. Rembrandt and his Wife, Saskia, 1636, B. 19 . vii 1, I. REMBRANDT'S MOTHER, Unfinished state. 1628: B. 354. 24 7, I. BEGGAR MAN AND BEGGAR WOMAN CON- VERSING. 1630. B. 164 . 24 20, I. CHRIST DISPUTING WITH THE DOCTORS: SMALL PLATE. 1630. B. 66 . 25 23, I. BALD-HEADED MAN (REMBRANDT'S FA- THER?) In profile r.; head only, bust added after- wards. 1630. B. 292. First state, the body being merely indicated in ink . 26 38, II. THE BLIND FIDDLER. 1631. B. 138 . 27 40. THE LITTLE POLANDER. 1631. B. 142. 139. THE QUACKSALVER. 1635. B. 129. 164. A PEASANT IN A HIGH CAP, STANDING LEANING ON A STICK. 1639. B. 133 . -

A Catalogue of Rembrandt's Etchings

Fk-.oVO, UU«xH Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Brigham Young University http://www.archive.org/details/catalogueofrembrOOhind a' catalogue of rembrandt's etchings CHRONOLOGICALLY ARRANGED AND COMPLETELY ILLUSTRATED B y ARTHUR M. HIND OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM SLADE PROFESSOR OF FINE ART IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. I INTRODUCTION AND CATALOGUE WITH FRONTISPIECE IN PHOTOGRAVURE, AND TEN PLATES ILLUSTRATING STUDIES FOR THE ETCHINGS METHUEN AND CO. LTD. 36 ESSEX STREET W.C. LONDON First Published February igis Second Edition, revised and in part rewritten . '9^3 THE LIBRARY BRIGHAM YOUWG UIN/IVERSIT^ PROVO, UTAH PREFACE THE present catalogue is a revised edition of the one which appeared in 1912 in my Rembrandt's Etchings, an Essay and a Catalogue, with some Notes on the Drawings. The Introduction is also composed to a large extent of material from the same volume, but revised and re-arranged with the definite object of providing such notes as would be of most use to the student and collector of Rembrandt's etchings (e.g. in the addition of a list of values). The volume of plates, to which a few subjects have been added since 1912, will no doubt be of service for purposes of identifica- tion, and will, I hope, appeal equally to the amateur or artist who merely wishes to be reminded of this incomparable series of subjects. For drawing my attention to new states or other details of description in the Catalogue, I would express acknowledgment to Jhr. Mr. J. F. -

The Exploration of Light As a Means of Expression in the Intaglio Print Medium Mary Vasko

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses Thesis/Dissertation Collections 8-7-1972 The Exploration of Light as a Means of Expression in the Intaglio Print Medium Mary Vasko Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Vasko, Mary, "The Exploration of Light as a Means of Expression in the Intaglio Print Medium" (1972). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EXPLORATION OF LIGHT AS A MEANS OF EXPRESSION IN THE INTAGLIO PRINT MED I UH by Sister Mary Lucia Vasko, O.S.U. Candidate for the Master of Fine Arts in the College of Fine and Applied Arts of the Rochester Institute of Technology Submitted: August 7, 1372 Chief Advisor: Mr. Lawrence Williams TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . i i i INTRODUCTION v Thesis Proposal V Introduction to Research vi PART I THESIS RESEARCH Chapter 1. HISTORICAL BEGINNINGS AND BACKGROUND OF LIGHT AS AN ARTISTIC ELEMENT THE USE OF CHIAROSCURO BY EARLY ITALIAN AND GERMAN PRINTMAKERS INFLUENCE OF CARAVAGGIO ON DRAMATIC LIGHTING TECHNIQUE 12 REMBRANDT: MASTER OF LIGHT AND SHADOW 15 Light and Shadow in Landscape , 17 Psychological Illumination of Portraiture . , The Inner Light of Spirituality in Rembrandt's Works , 20 Light: Expressed Through Intaglio . Ik GOYA 27 DAUMIER . 35 0R0ZC0 33 PICASSO kl SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION OF RESEARCH hi PART I I THESIS PROJECT Chapter Page 1. -

Remembering Rembrandt

For Immediate Release 13 February 2006 Contact: Hannah Schmidt 020.7389.2964 [email protected] Remembering Rembrandt ... CHRISTIE’S CELEBRATES REMBRANDT’S 400TH ANNIVERSARY Old Master, Modern and Contemporary Prints Wednesday, 29 March 2006 Christie’s London London – On July 15, 1606, one of the world’s most versatile, innovative, and influential artists Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn (1606-1669) was born in Leiden. Four hundred years later, Christie’s joins the celebrations of the anniversary of the master’s birth. An important group of fifty-five etchings by the artist from the collection of Dutch industrialist and patron, G.A.H. Buisman Jzn. will be offered alongside the 29 March sale of Old Master, Modern and Contemporary Prints in London. “This superb private collection lends a fascinating insight into the technique and mastery of the artist’s graphic oeuvre and with estimates starting at just £1,500 offers an excellent opportunity to collect an original by this famous artist in his 400th anniversary year,” said Richard Lloyd, Head of Christie’s Print Department. Rembrandt was a multi-talented artist, acquiring international fame not only as painter and draughtsman but also for his graphic works. He explored different forms, styles and subjects throughout his artistic life, with his first etching dating to circa 1626 and his last from 1665. The strength of his reputation as one of the most important graphic artists remains to this day. The collection to be sold at Christie’s reflects the broad range of subjects that Rembrandt addressed from portraits, and self-portraits, to landscapes, allegorical scenes, mythological and biblical stories as well as animal studies. -

Annual Report 1975

mm ; mm .... : ' ^: NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ANNUAL REPORT 1975 Property of the National Gallery of Art Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 70-173826 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D C. 20565. Copyright © 1976, Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art Inside cover photograph by Robert C. Lautman; photograph on page 91 by Helen Marcus; all other photographs by the photographic staff of the National Gallery of Art. Frontispiece: Bronze Galloping Horse, Han Dynasty, courtesy the People's Republic of China CONTENTS 6 ORGANIZATION 9 DIRECTOR'S REVIEW OF THE YEAR 20 DONORS AND ACQUISITIONS 47 LENDERS 50 NATIONAL PROGRAMS 50 Extension Program Development and Services 51 Art and Man 51 Loans of Works of Art 61 EDUCATIONAL SERVICES 61 Lectures, Tours, Texts, Films 64 Art Information Service 65 DEPARTMENTAL REPORTS 65 Curatorial Departments 66 Graphic Arts 67 Library 68 Photographic Archives 69 Conservation Treatment and Research 72 Editor's Office 72 Exhibitions and Loans 74 Registrar's Office 74 Installation and Design 75 Photographic Laboratory Services 76 STAFF ACTIVITIES 82 ADVANCED STUDY AND RESEARCH, AND SCHOLARLY PUBLICATIONS 86 MUSIC AT THE GALLERY 89 PUBLICATIONS SERVICE 90 BUILDING MAINTENANCE, SECURITY AND ATTENDANCE 92 APPROPRIATIONS 93 EAST BUILDING 94 ROSTER OF EMPLOYEES ORGANIZATION The 38th annual report of the National Gallery of Art reflects another year of continuing growth and change. Although formally established by Congress as a bureau of the Smithsonian Institution, the National Gallery is an autonomous and separately administered organization and is gov- erned by its own Board of Trustees. -

Open Access Version Via Utrecht University Repository

Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka 3930424 March 2018 Master Thesis Art History of the Low Countries in its European Context University of Utrecht Prof. dr. M.A. Weststeijn Prof. dr. E. Manikowska 1 Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Index Introduction p. 4 Historiography and research motivation p. 4 Theoretical framework p. 12 Research question p. 15 Chapters summary and methodology p. 15 1. The collection of Stanisław August 1.1. Introduction p. 18 1.1.1. Catalogues p. 19 1.1.2. Residences p. 22 1.2. Netherlandish painting in the collection in general p. 26 1.2.1. General remarks p. 26 1.2.2. Genres p. 28 1.2.3. Netherlandish painting in the collection per stylistic schools p. 30 1.2.3.1. The circle of Rubens and Van Dyck p. 30 1.2.3.2. The circle of Rembrandt p. 33 1.2.3.3. Italianate landscapists p. 41 1.2.3.4. Fijnschilders p. 44 1.2.3.5. Other Netherlandish artists p. 47 1.3. Other painting schools in the collection p. 52 1.3.1. Paintings by court painters in Warsaw p. 52 1.3.2. Italian paintings p. 53 1.3.3. French paintings p. 54 1.3.4. German paintings p. -

Fifty Short Sermons by T

FIFTY SHORT SERMONS BY T. De WITT TALMAGE COMPILED BY HIS DAUGHTER MAY TALMAGE NEW ^SP YORK GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY TUB NBW YO«K PUBUC LIBRARY O t. COPYRIGHT, 1923, BY GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY 1EW YO:;iC rUbLiC LIBRMIY ASTOR, LENOX AND TILDEN FOUNDATIONS R 1025 L FIFTY SHORT SERMONS BY T. DE WITT TALMAGE. II PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA y CONTENTS I The Three Crosses II Twelve Entrances . III Jordanic Passage . IV The Coming Sermon V Cloaks for Sin /VI The Echoes . VII A Dart through the Liver VIII The Monarch of Books . JX The World Versus the Soul ^ X The Divine Surgeon XI Music in Worship . XII A Tale Told, or, The Passing Years XIII What Were You Made For? XIV Pulpit and Press . XV Hard Rowing . XVI NoontiGe of Life . XVII Scroll oi Heroes XVIII Is Life Worth Living? , XIX Grandmothers , ,. j.,^' XX The Capstoii^''''' '?'*'''' XXI On Trial .... XXII Good Qame Wasted XXIII The Sensitiveness of Christ XXIV Arousing Considerations Ti CONTENTS PAGE XXV The Threefold Glory of the Church . 155 XXVI Living Life Over Again 160 XXVII Meanness of Infidelity 163 XXVIII Magnetism of Christ 168 XXIX The Hornet's Mission 176 XXX Spicery of Religion 182 XXXI The House on the Hills 188 XXXII A Dead Lion 191 XXXIII The Number Seven 196 XXXIV Distribution of Spoils 203 XXXV The Sundial of Ahaz 206 XXXVI The Wonders of the Hand . .210 XXXVII The Spirit of Encouragement . .218 XXXVIII The Ballot-Box 223 XXXIX Do Nations Die? 229 XL The Lame Take the Prey . -

Rembrandt's Three Crosses

Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum Spotlight Series: October 2008 By Paul Crenshaw, assistant curator for prints and drawings and senior lecturer in art history One of the most dynamic prints ever made, Rembrandt van Rijn’s The Three Crosses (1653) displays technical innovation and engagement with the human subjectivity of Rembrandt van Rijn The Three Crosses, 1653 Drypoint (4th state), 15 1/4 x 17 13/16" Christ’s death. A torrential downpour of lines Gift of Dr. Malvern B. Clopton, 1930 envelopes dozens of figures on the hill of Rembrandt van Rijn Golgotha, where Christ is pictured crucified The Three Crosses, 1660-61 Etching and drypoint (4th state)tate) amidst the two thieves. Even though it is an 15 1/4 x 17 13/16 " Gift of Dr. Malvern B. Clopton, 1930 inherently tragic subject commonly portrayed in Christian tradition, never before had it been staged with such sweeping emotional force. Rembrandt was inspired by the text of the Gospels (Matthew 27:45–54) proclaiming that a darkness covered the land from noon to three o’clock, when Jesus cried out with a loud voice, “Elí, Elí, lemá sabachtháni?” (“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”). When Jesus died, the passage continues, the earth shook, rocks split, tombs opened, and the bodies of many sleeping saints arose. To achieve these supernatural effects, Rembrandt employed the kind of bold technical ingenuity that helped define him as one of the most significant printmakers of his age. The Kemper Art Museum impression is a fine example of the fourth state of the print, which gives a dramatically different tenor and narrative focus to his subject than earlier states did. -

Rembrandt's 1654 Life of Christ Prints

REMBRANDT’S 1654 LIFE OF CHRIST PRINTS: GRAPHIC CHIAROSCURO, THE NORTHERN PRINT TRADITION, AND THE QUESTION OF SERIES by CATHERINE BAILEY WATKINS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Catherine B. Scallen Department of Art History CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2011 ii This dissertation is dedicated with love to my children, Peter and Beatrice. iii Table of Contents List of Images v Acknowledgements xii Abstract xv Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Historiography 13 Chapter 2: Rembrandt’s Graphic Chiaroscuro and the Northern Print Tradition 65 Chapter 3: Rembrandt’s Graphic Chiaroscuro and Seventeenth-Century Dutch Interest in Tone 92 Chapter 4: The Presentation in the Temple, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, Entombment, and Christ at Emmaus and Rembrandt’s Techniques for Producing Chiaroscuro 115 Chapter 5: Technique and Meaning in the Presentation in the Temple, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, Entombment, and Christ at Emmaus 140 Chapter 6: The Question of Series 155 Conclusion 170 Appendix: Images 177 Bibliography 288 iv List of Images Figure 1 Rembrandt, The Presentation in the Temple, c. 1654 178 Chicago, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1950.1508 Figure 2 Rembrandt, Descent from the Cross by Torchlight, 1654 179 Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, P474 Figure 3 Rembrandt, Entombment, c. 1654 180 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1992.5 Figure 4 Rembrandt, Christ at Emmaus, 1654 181 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1922.280 Figure 5 Rembrandt, Entombment, c. 1654 182 The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1992.4 Figure 6 Rembrandt, Christ at Emmaus, 1654 183 London, The British Museum, 1973,U.1088 Figure 7 Albrecht Dürer, St. -

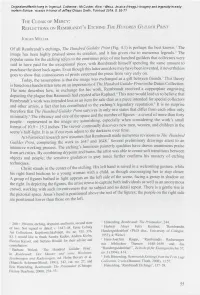

Of All Rembrandt's Etchings. the Hundred Guilder Print (Fig. 4.1)

Originalveröffentlichung in: Ingersoll, Catherine ; McCusker, Alice ; Weiss, Jessica (Hrsgg.): Imagery and ingenuity in early modern Europe : essays in honor of Jeffrey Chipps Smith, Turnhout 2018, S. 55-71 The Cloak of Mercy: Reflections on Rembrandt’s Etching The Hundred Guilder Print Jurgen Muller Of all Rembrandt’setchings. The Hundred Guilder Print (Fig. 4.1) is perhaps the best known.1 The image has been highly praised since its creation, and it has given rise to numerous legends.2 *The popular name for the etching refers to the enormous price of one hundred guilders that collectors were said to have paid for the exceptional piece, with Rembrandt himself spending the same amount to purchase the sheet back again. Even though this latter anecdote may have been invented, it nevertheless goes to show that connoisseurs of prints esteemed the piece from very eaily on. Today, the assumption is that the image was exchanged as a gift between friends? This theory is based on a handwritten note on an impression of The Hundred Guilder Print in the Dutuit Collection. The note describes how, in exchange for his work, Rembrandt received a copperplate engraving depicting the plague that Raimondi had created after Raphael.4 This note would lead us to believe that Rembrandt’s work was intended less as an item for sale than as a piece intended for special collectors and other artists, a fact that has contributed to the etching’s legendary reputation.5 *It is no surprise therefore that The Hundred Guilder Print survives in only two states that differ from each other only minimally/’ The vibrancy and size of the space and the number of figures - a crowd of more than forty people - represented in the image are astonishing, especially when considering the work’s small format of 10.9 x 15.3 inches.